A wooden chest, a breeches pocket, and a year-old fight over a seat in Congress

A wintry chill blanketed Rensselaer County, a huge trapezoid of land east of the Hudson River across from Albany, New York, on the night of January 6, 1793, when four horsemen tied up at John and Anne Van Alen’s place. Van Alen, a prosperous farmer, surveyor, and merchant, was standing as the Federalist candidate for the U.S. House of Representatives in the multi-day national election under way. One rider, John Van Valkenburgh, brought in a wooden container and several canvas-bound books—the ballot box and poll books being used to record the county’s voting on that day in the town of Rensselaerwyck. Anne Van Alen pointed to a large locking chest whose key she proffered. Van Valkenburgh placed the books and box inside and locked the chest. He would later testify under oath that nothing illegal happened while the ballot box and its attendants were spending the night in the Van Alen house.

During their overnight stay, which may or may not have been scheduled, Van Valkenburgh and fellow Federalist election inspectors Jacob Barhyt, Jacob Schermerhorn, and Aaron Ostrander slept in their designated beds. Van Valkenburgh kept the key in his breeches pocket. Ostrander, a Rensselaer County coroner, later claimed to have placed a seal on the ballot box. In the morning the four rode to their next polling location, the home of Justice of the Peace Abner Newton, to continue the election. Shortly after election results were announced publicly on March 2, 1793, the revelation that the election records had overnighted at U.S. House of Representatives candidate Van Alen’s home as a contentious campaign was ending triggered accusations of vote tampering, corruption, and fraud. The dispute went all the way to Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, for adjudication by the Congress.

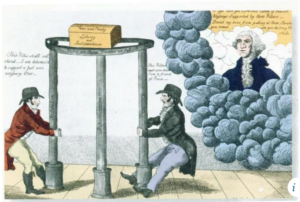

In 1788, George Washington had been the republic’s undisputed leader. His leadership during the Revolutionary War had unanimously carried Washington into the presidency without resort to personal politicking or the party organizations that practiced what the general regarded as a dark and self-interested art. Washington condemned political parties as “likely in the course of time and things, to become potent engines, by which cunning, ambitious and unprincipled men will be enabled to subvert the power of the people.”

That lofty disdain did not age well. Other men who also had fought in the Revolution and who also ascribed to republican principles nonetheless understood that practical political power mattered as much in America as the principles expressed in the Declaration of Independence. To govern, one had to win elections—and winning elections was the work of political parties. Ideological lines became party lines.

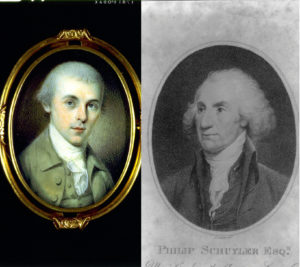

During the Confederation-era debate over the Constitution, two political factions emerged. Those who favored the Constitution as written became known as Federalists. Their opposition, initially the Anti-Federalists, came to call themselves the Democratic-Republicans. Federalists, who favored a strong central government, included founders like Alexander Hamilton, John Adams, Philip Schuyler, John Jay, and, despite his public scorn for parties, Washington himself. Federalism espoused responsible fiscal policy, establishment of a national bank, use of tariffs to protect domestic enterprise, industrialization, and cordial relations with former overlord Great Britain. Most Federalists read the Constitution broadly, interpreting the document as seemed practical. The Democratic-Republicans, led by Thomas Jefferson, included James Madison, James Monroe, New York Governor George Clinton, and others whose wealth resided in land and agriculture. Democratic-Republicans endorsed a weaker federal government with limited ability to tax; they also favored amity with France, America’s great wartime ally—and Britain’s sworn foe—and a narrow interpretation of the Constitution.

In the 1788 election, the first under the newly ratified Constitution, George Washington espoused a strong central government. Federalists won a majority in the Senate and the House of Representatives. Defeat taught Jefferson and chastened supporters that the path to power in the new government lay in strong party affiliations and an organized approach to electioneering. Two years later, Jefferson’s team gained Senate seats and a majority in the House of Representatives when the states of Kentucky and Vermont joined the union.

The Federalists and Democratic-Republicans began muscling up their party organizations. Eyeing the next campaign, the parties developed national and local structures and platforms. By the campaign year of 1792, party allegiances were solidifying nationwide. The Federalist camp included New England farmers, the large landed patroons—longtime landholders dating from Dutch settlement in the region —of New York, German farmers in eastern Pennsylvania, and slave-holding planters in the Deep South. Added to this conglomeration were ship owners and ship builders along the Atlantic coast and merchants, lawyers, and financiers in major urban areas. Democratic-Republican tickets drew support from small farmers and rugged inhabitants of the 14 states’ western frontiers. As more states joined the union and the country’s population expanded westward, it dawned on Federalists that unless the party aggressively held on to congressional seats it already controlled, especially in New York and New England, it would be out of power.

In New York, a particular congressional district illustrated the parties’ rivalry. In early 1792 that state’s legislature created more counties and began reapportioning 10 congressional districts. One district combined two newly minted counties, Rensselaer and Clinton. This congressional district was unique because it comprised two non-contiguous counties separated by the newly renamed Washington County, the president’s moniker having been deemed a better choice than its predecessor, “Charlotte,” after King George III’s wife.

Rensselaer County, across the Hudson River from state capital Albany, advertised its origins and orientation in its name. Since the heyday of the Dutch colony New Netherland, the Van Rensselaer clan had controlled vast acreage in that vicinity east and west of the river. With independence, a deeply rooted Hudson Valley manorial aristocracy, peppered with names like Livingston and Philipse, gravitated along with the Van Rensselaers to the Federalist cause. Of the valley’s patroons, only the downstate Van Cortlandt family embraced Jefferson’s ideas, as did voters in largely unsettled upstate Clinton County, near the Canadian border, reflecting the frontier’s less tradition-bound outlook and the Anti-Federalist political views of its namesake, Governor George Clinton.

New York’s congressional reapportionment dragged into late December, hobbling all candidates. Not knowing in which districts they were to be running, office-seekers hesitated to stake out positions in newspapers or on handbills.Winter clamped down; it became harder to travel and assemble crowds. Neither the Federalist John Van Alen nor the Democratic-Republican Henry K. Van Rensselaer (1744-1816) even garnered official nomination until New Year’s Day 1793. To choose between the two, voters would have to rely on what they knew of the men’s past records and current political connections.

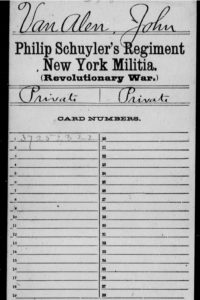

John Van Alen, the Federalist, was born in 1749. He had grown up to be a prominent Albany-area surveyor, farmer, and merchant. His name appears as a private on muster rolls of the 7th Regiment, Albany County Militia, indicating he was eligible for military service. With the onset of the rebellion, New York became a hotbed of internecine suspicion, especially around Albany, where patriots and Loyalists were jockeying for local political control. By 1777 the patriots seemed to have the upper hand in the region. That spring, asked to swear allegiance to New York and the United States, Van Alen waffled, a display of equivocation impolitic enough that in May 1777 the Albany County Committee of Safety ordered Van Alen jailed. He remained in stir until October, when British General John Burgoyne and his army surrendered at Saratoga. In November, with the tide now in the patriots’ favor, Van Alen took the oath without hesitation and was sprung. Within the year he had purchased 400 acres of land east of Albany, near Rensselaerwyck Manor, the ancestral Van Rensselaer fief. In 1791, newly formed Rensselaer County named Van Alen justice of the peace and assistant judge. By the time Van Alen committed to running for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1792, he had the endorsement of Stephen Van Rensselaer III, patroon of Rensselaerwyck Manor and a prominent Federalist.

John Van Alen, the Federalist, was born in 1749. He had grown up to be a prominent Albany-area surveyor, farmer, and merchant. His name appears as a private on muster rolls of the 7th Regiment, Albany County Militia, indicating he was eligible for military service. With the onset of the rebellion, New York became a hotbed of internecine suspicion, especially around Albany, where patriots and Loyalists were jockeying for local political control. By 1777 the patriots seemed to have the upper hand in the region. That spring, asked to swear allegiance to New York and the United States, Van Alen waffled, a display of equivocation impolitic enough that in May 1777 the Albany County Committee of Safety ordered Van Alen jailed. He remained in stir until October, when British General John Burgoyne and his army surrendered at Saratoga. In November, with the tide now in the patriots’ favor, Van Alen took the oath without hesitation and was sprung. Within the year he had purchased 400 acres of land east of Albany, near Rensselaerwyck Manor, the ancestral Van Rensselaer fief. In 1791, newly formed Rensselaer County named Van Alen justice of the peace and assistant judge. By the time Van Alen committed to running for the U.S. House of Representatives in 1792, he had the endorsement of Stephen Van Rensselaer III, patroon of Rensselaerwyck Manor and a prominent Federalist.

In the 17th century, the Dutch West India Company had granted diamond merchant Killiaen Van Rensselaer the right to develop a plantation or “patroonship” with a tenant population near the future state capital. Occupying land purchased from local Indian tribes, patroonships ran much like feudal fiefdoms populated by farmers and tradesmen brought from Europe to live and work. Rensselaerwyck became the most successful manor of the several in New Netherland. Even after the English booted out the Dutch in 1664, the Van Rensselaer estate ran 23 miles north and south along the Hudson and 24 miles east and west, more a million acres in total. By the time Stephen Van Rensselaer III became patroon, the new state government had organized Rensselaerwyck into counties. However, the patroon still owned the land and his tenant farmers still owed him fealty.

It paid to have Stephen Van Rensselaer as a friend, especially in politics. He had married into the well-connected Schuyler family, whose sons-in-law also included Alexander Hamilton, architect of the Federalist Party. Van Rensselaer, 28, had sought and won office in New York’s assembly for two years in 1789, then served for another five years in the state senate. His career also included stints as New York’s lieutenant governor under John Jay and a militia general’s commission. As one chronicler put it, “wealth and his connections, combined with a gentle temper and unassuming manners, made him a gentleman, and gave him a high position.”

Besides having a Van Rensselaer as a backer, John Van Alen was running against Hendrick Killi

aen (Henry K.) Van Rensselaer, Stephen’s third cousin and a bona fide hero of the Revolution. Commanding New York militia under George Washington in 1776 during the American retreat across New Jersey, Henry had been wounded in the head near New Brunswick. In July 1777 at Fort Ann, 11 miles south of Lake Champlain, Henry Van Rensselaer, now serving under Major General Philip Schuyler, had helped deliver a pivotal blow to a British army whose invasion, aimed at Albany, meant to isolate New England from the rest of the rebel colonies. Commanding the 4th Albany County Militia Regiment in a furious fight, Colonel Van Rensselaer, despite grievous wounds—a musket ball pieced his right thigh, shattering the femur—urged his men on. Their valor delayed Burgoyne’s army by several weeks, helping to thwart the British strategy. His Fort Ann wound was Van Rensselaer’s claim to fame. After more than a year convalescing—the slug stayed in his body until his death in 1816; the doctor who extracted it said it looked like a pancake—he was posted near Albany for the rest of the war. Upon independence, Henry moved to Rensselaerwyck’s Green Bush area, where he hobbled about, well known as a veteran and a politician elected several times to the state assembly.

In the brief campaign of 1792-93, Stephen Van Rensselaer did all he could for John Van Alen, likely to the point of touting his man to his tenants. The patroon denied accusations that he had threatened tenants with legal action if they voted otherwise, but a contemporary observer wrote, “the people of the Manor have been influenced by the Patroon.” The patroon certainly left nothing to chance. He sent factotum Thomas Witbeck as campaign manager to hustle votes for Van Alen in sparsely populated Clinton County. After the election ended, Witbeck was busy scouring Rensselaer County, doing damage control for Van Alen when accusations of voter fraud surfaced from Henry Van Rensselaer’s camp. Witbeck’s preferred remedy was to require election officials to swear oaths of good conduct during the recent voting.

Congressional elections in the 18th century were run far differently than today. There was no uniform date; voting took place over multiple days as poll workers traveled a circuit among towns. The 1793 Van Alen/Van Rensselaer contest took place the first week in January, while in New York City polls did not open until January 22. Election rules defaulted to local prerogative. Where populations were denser, voting took place in coffee houses, pubs, hotels, and private homes. In rural areas like Rensselaer and Clinton counties, polling mainly went on at taverns and residences. Sworn inspectors administering the election were responsible for controlling the ballot boxes and canvas-bound books, which afterward they submitted to a nine-man joint committee appointed by the New York State’s senate and assembly.

The joint committee was responsible for “canvassing and estimating” the results. That panel’s adjudication, completed on February 19, was not publicly available until March 2, when newspapers carried the official results, listing winners for each congressional district without any indication of the number of votes cast for the respective candidates. A week earlier, however, the New York Journal had reported the actual election results: Clinton County counted 214-32 for Van Rensselaer, but Rensselaer County went solidly Federalist, 1,133 to 656, for Van Alen. The final tally was John Van Alen’s 1,165 votes to Henry K. Van Rensselaer’s 870 votes. A third candidate, Thomas Sickles, got 12 votes. By March 2, 1793, Congress had seated John Van Alen in Philadelphia as the winner of the election.

Henry K. Van Rensselaer cried fraud. In a petition to the U.S. House of Representatives, he complained of “an undue election and return of John E. Van Alen” to Congress. He claimed that in Stephentown, the record showed more votes for Van Alen than the number of voters listed in the canvas-bound poll books. In Hoosick, another Rensselaer County town, Van Rensselaer charged, polling officials had not locked up the ballot box as mandated but only wrapped the box in “tape,” which in the parlance of the day meant securing something with a string or cord, a defense easily breached. And, referring to that sleepover by Van Valkenburgh and associates, Van Rensselaer declared that on that night Van Alen, despite not being an election inspector, “had in his possession the ballot box of the town of Rensselaerwyck.” This charge was the crux of Henry Van Rensselaer’s argument: he believed that the election inspectors had purposely withheld votes to which he was entitled. Van Rensselaer offered no specific evidence about the ballots supposedly changed or added, but the implied circumstantial evidence seemed clear to him and his supporters.

Thomas Witbeck notified Van Alen in Philadelphia of Van Rensselaer’s challenge, wishing the winner “fortitude sufficient to oppose those villainous acts.” Witbeck then went about finding evidence to counter Van Rensselaer’s claims of foul play. He succeeded in securing several statements from interested parties clearing the patroon’s candidate.

John Van Valkenburgh swore that in his role as an election inspector on the evening of January 6, 1793, he had taken poll books to Van Alen’s house and locked them securely in a chest provided by the candidate’s wife. The next day, he said, he and his companions opened the chest and took the materials to Abner Newton’s house, where more votes were cast and election inspectors approved of Van Valkenburgh’s actions, claiming the ballot box to have been perfectly safe at Van Alen’s house the night before.

Election inspector Aaron Ostrander testified that he personally had sealed the ballot box. The next day an inspector at Newton’s house found Ostrander’s seal to be unbroken. Jacob Barhyt and Jacob Schermerhorn acknowledged spending the night at the Van Alen home. Their testimony agreed precisely with the stories Van Valkenburgh and Ostander told. Schermerhorn swore Van Valkenburgh “kept the key in his breeches pocket and…slept with his breeches on during the said night.” At the Crowfoot Tavern, a polling place in Stephentown, election inspectors and the town clerk assuredWitbeck that no attempt by Van Rensselaer supporters could upset Van Alen’s lead. In Lansingburg, another town in Rensselaer County, the story was the same.

The House set about reviewing Van Rensselaer’s petition and assigned a committee to study the allegations. Federalist operative Witbeck continued to comb Rensselaer and Clinton counties for election inspectors willing to sign affidavits favoring Van Alen. In a letter, Witbeck claimed inspectors at the Stephentown poll in Rensselaer County to have been “all Men of Principle and the chosen Men of the Town” who could never have been responsible for such a “Villain’s act as the changing of the Ballot.” But the opinion among Democratic-Republicans was “that corruption in elections was the door at which corruption would creep into the House.”

The disabled war hero had lost an election to an opponent who had shown wavering loyalty to the new nation. Van Alen’s wartime behavior suggested he waited to see which way the patriot effort was going before he embraced the cause, tarnishing his bona fides. Van Rensselaer alleged corruption and fraud because the ballot box had spent a night at his adversary’s house. While the ballot box was at Van Alen’s house, it could have been tampered with, according to Van Rensselaer. In places like Stephentown vote tallies seemed shady. The Hoosick crew, when required to secure a ballot box overnight, had done the least possible.

On December 20, 1793, nearly a year after the election ended, the U.S. House of Representatives took up the question of Henry K. Van Rensselaer’s petition. Ten days earlier, a standing committee on elections had been assigned to evaluate the former colonel’s charges. Coming down squarely on behalf of Van Alen, who by now had been in office for nearly 10 months, the standing committee told the House said that committee members felt that the “time, place and manner” of holding elections was expressly vested in state legislatures; in other words, only New York law applied. The committee was quoting Article 1, Section 4 of the new Constitution. Committee members also were satisfied that there were no grounds for alleging fraud. Language in New York election law indicated that under certain circumstances votes might be rejected or omitted by accident in the general canvass.

The standing committee also found that that Congress lacked authority to inquire into elections because states’ “different customs” did not lend themselves to uniform congressional control. The committee also was satisfied that there were no grounds on which to base a charge of fraud regarding the ballot box incident. The committee felt the lack of evidence demonstrated the box had not been tampered with. What’s more, there were no ground for charging Van Alen as an “accessory to any unfair practices in the election.”

After the standing committee on elections presented its findings to the House on December 20, Congressman Richard Bland Lee (F-Virginia) stepped forward to ask a question: if state law did not deem the activities a problem, why should the irregularities Van Rensselaer alleged nullify the election results? Lee said none of the irregularities seemed sufficient “to vitiate the returns of the votes made by the inspectors, who were sworn officers, and subject to pains and penalties for failure of duty.” If New York law was “to be observed as a sovereign rule of this occasion, the allegations do not state any facts be necessary as to require the interference of the House of Representatives,” Lee posited. And since it was an “indispensable requisite” of representative government that a choice should be made at an election, should not the principle be established “that a majority of legal votes, legally given, should decide the election?” Should “partial corruption be sufficient to nullify an election or only that part which was subject to corruption, leaving the election to be decided by the sound votes, however few?” Playing to his audience, Lee said he thought not.

Lee closed with a capstone for the logic he had been laying out. According to the Virginian, the nine-man joint committee of the New York legislature held that the majority of the votes in the contested counties were sound. There might have been some irregularities, but far and away most votes were on the level. Since John Van Alen had the plurality of the major part of these honest votes, why should this not be the criterion for a decision? Lee’s last point became the basis for the opinion rendered by the House Committee on Elections: Van Alen should retain his seat in Congress—period.

Objections immediately assailed the committee report. Van Rensselaer supporters, arguing that both houses of Congress had the right to judge one another’s members’ qualifications, claimed that deferring to New York law infringed on Van Rensselaer’s right to a fair election result. Van Rensselaer’s allies also alleged corruption in the Van Alen camp based on the ballot box layover at that candidate’s house. Democratic-Republicans said Congress in its report seemed to be condoning corruption as long as the malfeasance was small-scale. It was apparently no big deal that a ballot box spent a night at a candidate’s house. The parties involved swore that the box had not been tampered with, so there was nothing wrong; Van Alen could not be charged as an “accessory to any unfair practices in the election.” Van Alen supporters claimed Congress lacked standing to judge elections because varying state customs were beyond congressional control.

Resuming consideration of the election committee’s report after four days, the House upheld the committee’s findings; even if there were irregularities in Stephentown and Hoosick, the district’s remaining votes showed Van Alen to have a majority. The House declared that Henry Van Rensselaer’s petition did not “state [enough] corruption, nor irregularities of sufficient magnitude, under the law of New York, to invalidate the election and return of John E. Van Alen to serve as a member of this House.” Van Alen remained in Congress, was reelected twice, and went on to serve two years in the New York State Assembly. He died in 1807, his reputation still dogged by unresolved suspicions about just how quietly that wooden ballot box had spent a cold night at his house in January 1793.

This story is an American History magazine Online Exclusive.