In 1985, author and artist Peter Svenson was looking for farmland in Virginia’s Shenandoah Valley. Exasperated in his search, he asked a local farmer, “Well, do you know anyone around here who’s got land for sale?” “I’ll sell you forty acres,” was the unexpected reply. Svenson eagerly bought that 40 acres near Cross Keys. He had never worked the land before, and he had little knowledge of the Civil War. To his astonishment, he discovered his property was the site of core fighting during the June 8, 1862, Battle of Cross Keys. The Confederate victories there and the next day at nearby Port Republic marked the conclusion of Brig. Gen. Stonewall Jackson’s legendary Shenandoah Valley Campaign. Svenson documented his experiences in the 1992 book “Battlefield: Farming a Civil War Battleground.” His prose poignantly describes both his struggles with farm machinery and the stunning realization that Americans fought and died in his hay fields and woodlots. His unique look at the war was reprinted in 2017, and the following excerpted material presents some of his journey of discovery.

In this passage, Svenson discusses his growing connection to the land, fueled by a deep sensitivity to the horrible human ordeal that occurred on his farm in 1862.

From time to time, people ask me if I have ever seen ghosts on the battlefield. No fewer than 150, and possibly as many as 350 men, Union and Confederate, perished here on that fatal Sunday. Death struck each soldier, here as in any other battle, in a straightforward way. The trajectory of a piece of metal ended upon a target of flesh, the odds of good aim and bad luck coinciding perfectly. For the soldiers who looked death in the face and died, the experience could not have ended without a metaphysical transformation of some sort.

As mortality passed forever in the midst of searing pain, I believe that souls must have been left hovering. There is no other way to say it. Of life after death I know nothing, or next to nothing. Like anyone else, I theorize and build soaring arches of faith, but my conjecture about the moment of corporeal dissolution remains difficult to put in words without veering into the realm of Special Effects. The farmboy in butternut who was reluctant to abandon his kinfolk, or the blue-uniformed immigrant who cherished memories of the old country—each dying individual was transformed in some incomprehensible way. Is it wrong to surmise that the soul flew up and away?

Seen or unseen, ghosts must have been here. But to answer the question: no, I have never seen ghosts on the battlefield. This is not to say I am unmoved in the presence of departed spirits, for I am. The very first time I walked on the battlefield, there seemed to be a faint emanation that may have been germane to these considerations. It was nothing I could put my finger on. For lack of an answer, I dismissed it as a product of my imagination. I soon realized, however, that it had nothing to do with me, no matter how susceptible my brain was to the power of suggestion. The overgrazed pasturage, with its barn and machine shed, was adding up to more than the sum of its physical characteristics.

Granted, it was a comely quarter, distanced from the blur of traffic, peaceful as any 40 acres could be. The pastoralism set me aquiver, to be sure, but there was more to it. In the lengthening shadows of that first afternoon, as I perambulated the fields among the skittish cattle that fled my approach, yet followed from behind as though I were a Pied Piper, I pondered the evidence.

And then, Eureka! I understood. The thing I sensed was that people had been here before, en masse. At times, I have noted a comparable intimation after a public auction, when the last item of furniture has been carted off and the buzz of the crowd and the auctioneer’s warble still echo in my ears. A whiff of humanity lingers, a subtle indefinable something, but it is not an olfactory sensation. A similar presence lingered in these pastures 123 years after the battle.

Having respect for the dead means that future generations don’t pave over cemeteries for parking lots. There is no law, however, that says cemeteries can’t be tourist attractions. A headstone, plain or fancy, reminds onlookers that so-and-so existed within the confines of two dates.

In Harrisonburg, there are more than 250 Confederate graves in a quadrant of the oldest cemetery. Each small marble marker reads like a word in a chilling sentence, or a sentence in a numbing chapter. The regularity with which the markers are placed, row upon row like a marching battalion, suggests an orderliness, a solidarity of purpose. The Southern Cause is given shape and substance. I know it was an act of practicality, the organizing of corpses in a limited space, but still the geometry of the graves disturbs me. Death for any cause, lost or won, is not quite so cut and dried as a cemetery layout.

There are Union mass graves on the Cross Keys battlefield, but no one knows precisely where. A likely location may be not more than 100 feet from our new house. In the aftermath of Civil War battles, mass graves were dug with shovels and corpses were covered with less than two feet of earth. At Gettysburg and elsewhere, heavy rains exposed the bones of the dead during the weeks and months following interment. Given the passage of time, it seemed odd that treasure hunters had neither discovered nor plundered the mass graves at Cross Keys. Whatever the reason, far more than a century has passed, and nobody has stumbled upon the evidence. Once in a great while, sheer forgetfulness accounts for the survival of places and things. In this case, the abandoned Union dead were thrown together in unmarked ditches, their final camouflage as unknown soldiers, and they are still resting there.

Svenson’s piqued interest in the Battle of Cross Keys led him to do archival research on the fight. During a research trip he poured over the diary entries of a young Confederate officer who had crossed near his land, and had died in the June 9 fight at Port Republic.

Deep in the card catalogue of the Virginia Historical Society in Richmond, I came across a morsel of research that brought the battle home to me as no other item had done. More than information, it was a glimpse through a window that opened onto a frightened individual’s soul. On Sunday morning, June 8, 1862, 25-year-old Joseph H. Chenoweth, a major in the 31st Virginia Regiment, sat on his horse in a field to the south of our 40 acres and wrote in his diary.

By volunteering for duty, he had taken leave of a promising career as a mathematics teacher at Maryland Agricultural Institute. He had graduated second in his class from Virginia Military Institute. His diary, as well as his letter writing, attested to a finely wrought patriotism and sense of religion. He had acquired the habit of interrupting his observations from time to time with heartfelt, written prayers, and in doing so he may have been nursing a premonition of his own death.

His first entry for the morning gave his location as “Near Harrisonburg on the road to Port Republic, June 8th. 9 o’clock A.M. Cannon have been heard to the left of us near Port Republic. Gen. Jackson I doubt not understands his position, but I think we will have a hard battle soon.”

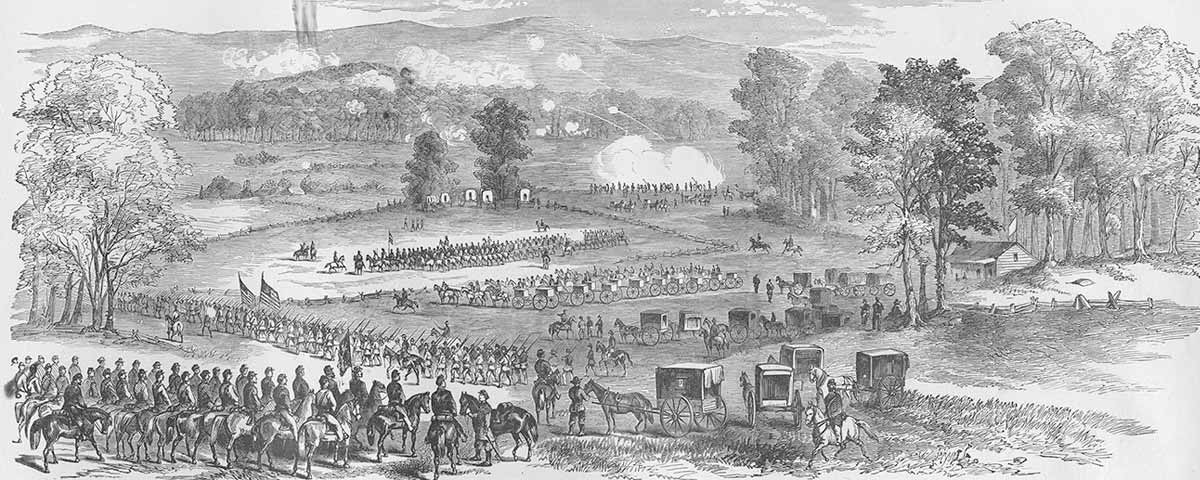

By 10 o’clock the Confederates’ long defensive line was at the ready and, with the emplacement of the Union batteries, the galling artillery exchange began. Chenoweth’s regiment was in a reserve position to the rear of center.

“Later 12 o’clock A.M. Heavy cannonade is being kept up on the side of us next to Harrisonburg. Some of our men I think have been wounded—I saw on going to the road. The 31st is supporting the battery which is engaged. I do not like our position, though it is a commanding one. We may possibly have our flank turned but Jackson is here if Frémont is with the enemy. Our movements yesterday and today are incomprehensible to me.”

Chenoweth meant that Jackson would be there to lead the army out of danger if the battle took a turn for the worse. It was a statement of faith. Old Jack was a hero and an inspiration. The ferocity of the barrage distressed the young major. He sat on his horse toward the rear of the center of the Confederate line and considered the fragility of his life and that of his fellow soldiers.

“Later—there is a lull in the firing—I know not why. My fervent prayer is that our Heavenly Father may lead our beloved country through the labyrinth of troubles which envelop her—and give peace to her persecuted and much-tried people. We seek not, O God, for conquest….”

The prayer rambled on, as if the act of writing it were a shield of sorts, and as Chenoweth wrote, the tide of the battle turned. The flank was holding. Chenoweth mustered more courage after this to the point where he could acknowledge a grim beauty to the fight.

“Later, 2:30 P.M. This is decidedly the warmest battle with which I have ever had anything to do. The artillery fire is superb—and the musketry is not so slow. We are in reserve, but the shells fly around us thick and fast. We will soon be into it.”

Now that the Confederates seemed to be gaining the upper hand, the bolder officers and men of the 31st Virginia were vexed by their lack of participation. Their inaction was ended in response to a renewed Union offensive. Chenoweth was getting a stronger taste of battle.

“Later, 4 P.M. We have been firing in the fighting and poor Lt. Whirly has been killed, shot thro’ the head. A cannon has been planted on our left, and several of our poor men have been wounded. I pity them from the bottom of my heart. We will be at it again soon I think. And, Oh God, I renew my earnest prayer for the forgiveness of my many sins and for strength. In the name of Thy Son, grant me mercy. Amen.”

With casualties nearby, the shadow of disaster cast a pall over the good news received earlier. Half an hour later, the artillery duel was still going strong, but Chenoweth steeled his nerves and reported what he saw: “Later, 4:30 P.M. The cannonading has recommenced and is very severe on the part of the enemy.”

Not quite two hours afterward, the firing ceased. Cheno-weth had weathered the worst of it and now he recorded a gentler scene: his regiment in repose.

“Later, 6:13 P.M. All is now quiet. Our regiment (31st) is lying down on line of battle, in full view of the enemy’s battery, which only one hour ago was pouring grape into the regiment’s noble soldiers! It tortures me to see them wounded. How many of them now, as they rest, looking quietly and dreamily up into the beautiful sky, are thinking of the dear ones at home, whom they have not, many of them, seen for twelve months. This is a hard life for us refugees who fight and suffer on without a smile from those we love dearest to cheer us up.”

Then, in a philosophical digression, Chenoweth wondered if the invading Yankees would need to be forcibly removed from the continent in order to reunite the divided nation.

“Can the convictive feelings of hatred which burn in the breasts of our Union neighbors be obliterated by a treaty of peace? Or will they be compelled to expatriate themselves–or be exiled deservedly–exiled from a land to which they have all proven themselves traitors in thought if not in deed?”

It was a protest against unjust persecution, and a solution that came straight from the bowers of make-believe. It showcased the young major’s ivory-tower innocence. He had no more understanding of hate than he had of his commanding general’s tactics.

During the night, the 31st Virginia was marched to Port Republic to rejoin the main body of Jackson’s army. Monday morning found the major committing to his diary the brisk beginnings of a new battle, but this time his regiment was in the thick of it. Chenoweth’s literary style shifted to nervous metaphor.

“Port Republic, June 9th, 1862—8 o’clock A.M. The ball is open again and we are from what I see and hear to have another hot day. It is [in] sheets this time. I may not see the result, but I think we will gain a victory though.”

The crossfire, in which he wrote, intensified. His diary stumbled to a halt with two disjointed sentences. “I do not think our men have had enough to eat. I can’t write on horseback.”

Chenoweth was killed shortly after he dismounted. Why did he leave the saddle? Did he feel too exposed? Did he decide to finish the paragraph on solid ground? In a memoir by his fellow soldier Joseph H. Harding, the following account describes his death:

“As the battle progressed, he was…advancing up the line encouraging the men and calling upon them to advance and follow where he led when he was shot, the ball entering just behind his left ear and passing entirely through the head. He fell without a groan with his sword still in his grasp pointed toward the enemy, nobly discharging his duty.”

After 10 years at Cross Keys, Svenson sold the farm and moved away. During a return visit, he found, to his chagrin, that the land had been altered. He wrote the following passage that described what he had seen in 2011 and sent it to The Washington Post as an op-ed, but it was never published. As he says, “It makes a fitting conclusion to this new edition of the book.”

Question: when is property no longer your property? Answer: when you haven’t owned it for 17 years and are staring at it across a barbed wire fence.

This was my experience recently in Cross Keys, Va., where I used to own a 40-acre hay farm that turned out to be situated at the epicenter of a Civil War battlefield.

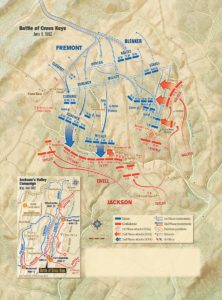

The Battle of Cross Keys, the penultimate clash in Stonewall Jackson’s Shenandoah Valley Campaign, was fought on June 8, 1862, and is singled out for uniqueness because of the wily tactics of a 60-year-old Confederate field commander, Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble, who led his relatively small force to unexpected victory over a much larger Union presence.

Now, after so long an absence, I’m looking at the rolling hay fields that I still practically know by heart, having driven farming equipment over them for 10 years, and walked them countless times.

With a map or guidebook in hand, armed with an elementary knowledge of the battle’s particulars, most visitors can figure out what happened and where, and in the process gain that spooky, spiritual thrill which often accompanies tours of battlegrounds from any era. The Cross Keys battlefield is easily walked, easily understood, and as others have said, one of the “prettiest” battlefields in Virginia.

Mindful of all this before I sold and moved away from my farm, I placed a preservation easement on the 40 acres in perpetuity with the Virginia Outdoors Foundation (VOF) in 1994—the first easement of its kind in the Cross Keys area. This initiative on my part did not come without a price. The farm became instantly devalued and difficult to sell because, in the place of limitless options for agriculture and agribusiness, there were strictures: no building or structure could be erected without permission of the VOF, no residential development, no commercial industry, and most importantly, no disturbance to the topography.

After two years of unsuccessful listings with realtors, I wound up selling the farm at auction, barely breaking even on my original investment. I was quite satisfied, however, knowing that I had done the right thing by preserving this historic acreage for all time.

Or so I thought. Fast-forward to 14 years later: the current landowner decides to build a horseback riding ring, more than an acre in size, breaching a ravine along the property line—basically filling it to a height of 12 feet and leveling off the top. Staffers at the VOF grant it approval. Giant yellow machines are brought in to do the work. The resulting flatness, considerably wider than the ring itself, looks like the deck of an aircraft carrier.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

As I stare at it from across the fence, I cannot think of a more incongruous intrusion upon the gently rolling terrain. There was obviously leftover soil, too, which got graded into an adjacent hillock like an oversize ski mogul. The ring itself has been packed with many truckloads of fine gravel, and board fence delineates its boundaries.

But there’s more. What the staffers at the VOF and the landowner didn’t realize—and apparently never bothered to find out—is that this particular ravine figured prominently in the 1862 battle, for it lies at the heart of the area where the Union troops advanced to meet the hidden Confederate line and were repulsed with frightful casualties. In other words, the ravine and its surroundings are as hallowed as hallowed ground gets. And now the ravine is no more.

So I’m standing there, looking across the barbed wire at this desecration that’s already four years old. Apparently, nobody did anything to try to stop it (I certainly wasn’t notified). Two adjectives, heedless and thoughtless, come to mind. I can hardly believe my eyes. As Grantor, I feel betrayed, and I also feel a sense of shame. In the intervening years, I moved on with my life, never doubting that the easement had teeth and was enforceable. Besides, I was under the impression that 1860s battlegrounds were all but sacrosanct in the public’s consciousness.

At this point, I can only make a plea, on behalf of all Americans, that the full measure of my preservation easement be honored. I’d like to see the Virginia Outdoors Foundation and the current landowner admit what I think is an egregious error, and immediately make amends. That same squadron of heavy equipment should be brought back to undo the desecration, so the ravine is no longer bridged by 12 feet of fill dirt. If it were returned to its original state, visitors to the Cross Keys battlefield, now and in the future, will be able to better visualize the attack and subsequent slaughter that transpired on a sunny late-spring day 150 years ago.

Peter Svenson is an artist and writer who now lives in Fayetteville, N.Y. His other books include, Starter Home: Discovering the Past in Central New York.