When Florida seceded from the Union on January 10, 1861, the new Confederacy viewed Pensacola’s naval shipyard and railroad link as invaluable assets to the Southern cause. On January 12, Florida and Alabama state troops, along with many local citizens, forced U.S. Commodore James Armstrong to surrender the naval shipyard. In the bargain, the Southerners also acquired a million-dollar dry dock, workshops, warehouses, barracks, a hospital, 175 cannons, projectiles and ordnance stores.

The shipyard and nearby railroad were indeed great prizes, but the Federal occupation of Fort Pickens, which commanded the harbor at the mouth of Pensacola Bay, nullified all these advantages. As long as Federal forces held Fort Pickens, the Confederates would not be able to use Pensacola Harbor effectively. Deprived of any shipments of goods and materials via the harbor, the railroad would be of little value in helping to supply the Rebel armies in the field; and the enemy presence at the fort posed a constant danger to any Confederate activity at the shipyard.

Lying at the western tip of Santa Rosa Island, Fort Pickens — like Fort Sumter in Charleston Harbor — presented a dilemma for Abraham Lincoln and his new administration. Both forts were occupied by Federal troops in Rebel territory. Fort Pickens, however, lay on the seacoast and could easily be reinforced by sea, whereas Fort Sumter, located well inside Charleston Harbor, could be cut off from naval support by well-placed Confederate artillery batteries around the harbor. Fort Pickens could never be isolated as long as the United States had a strong navy.

At the beginning of 1861, Fort Pickens stood empty. Fort McRee, across the harbor inlet from Fort Pickens, was occupied by a caretaker and his wife. The only U.S. troops in Pensacola — a small garrison of artillerists of Company G, 1st U.S. Artillery — were quartered in Fort Barrancas, an old Spanish fort just west of town. Their commander, Lieutenant Adam J. Slemmer, recognized his precarious position. He learned that Florida troops were gathering in town, and he suspected that Fort Barrancas would be seized along with the nearby naval shipyard. Shortly before midnight on January 8, 1861, guards at Fort Barrancas fired shots at figures lurking near the fort. Slemmer, fearing for the safety of the garrison, sensed that further hostilities were imminent. He reported that 20 men had been seen, although later accounts indicated that there were only two. At any rate, these ‘first shots of the war spurred Slemmer into action.

On January 10, the same day Florida seceded, Slemmer, with the support of Commodore Armstrong, evacuated his 51 soldiers, along with 30 sailors, from the shipyard and transported them to Fort Pickens. Named after Revolutionary War General Andrew Pickens, the fort was built to accommodate 250 guns and 1,200 men. Slemmer believed it would be the easiest of the three forts to defend and eventually reinforce. Two days later, the Florida troops occupied Forts Barrancas and McRee.

Any immediate attack on Fort Pickens was forestalled by the so-called Buchanan truce. Under this agreement, negotiated by U.S. Senator Stephen Mallory of Pensacola and President James Buchanan (who was still in office in January 1861), secessionists would not attempt to seize the fort as long as Federal reinforcements were not landed there. Temporarily safe from attack, Slemmer refused three Confederate demands for surrender. The political situation, however, was rapidly changing, and the fragile truce did not last long. Lincoln was inaugurated as president in March 1861, and he immediately ordered Union troops to reinforce Fort Pickens. In April (the same month that the Confederates bombarded Fort Sumter), Slemmer’s tiny garrison was reinforced by several companies, and Colonel Harvey Brown was put in command of the fort.

Meanwhile, on March 11, Brig. Gen. Braxton Bragg had assumed command of the approximately 7,000 Confederate troops in the Pensacola area. Bragg was a capable trainer and organizer of troops, and he lost no time in fortifying positions along the waterfront. He was unhappy, however, about his raw recruits’ lack of discipline and experience. Bragg contemplated attacking Fort Pickens, but did not believe he had the necessary means to mount a full-scale siege. He also knew that the Federal Navy had complete control of the Gulf, and thus believed that the fort would be untenable even if captured. Bragg failed to fully appreciate the fort’s strategic potential. Forts Barrancas and McRee were not sufficient to fully control the harbor. Without Fort Pickens, the Confederate occupation of Pensacola was meaningless, and Bragg could not take advantage of the military and commercial benefits of the harbor. Events were taking shape, however, that soon would force Bragg’s hand.

On September 14, 1861, the Confederate schooner Judah, moored to a wharf at the naval shipyard, was boarded and set ablaze by a raiding party from USS Colorado. Federal naval officers had learned that Judah was being outfitted as a privateer and determined to destroy her before she could put to sea. Judah was set on fire, and three of the Yankee raiders were killed. In retaliation for the burning of the schooner, Bragg ordered an attack on the Federal fortifications on Santa Rosa Island. His soldiers were restless and eager to have a go at the Yankees. Bragg ordered Brig. Gen. Richard H. Anderson to assemble an expeditionary force of about 1,100 men for the sortie.

Although he wanted to punish the Yankees for their egregious deed, Bragg seems to have had no intention of attempting to capture Fort Pickens itself. In a letter to his wife dated October 10, he declared that it was Billy Wilson and his crowd that I fondly hoped to destroy. Colonel William Wilson and five companies (C, D, F, H and K) of the 6th New York Volunteers were encamped about a mile east of Fort Pickens. Wilson, a New York City politician, was a colorful character, and his Zouaves were an undisciplined and unruly lot. The regimental mascot was a billy goat, which had been taught to butt with force and precision. Wilson’s force numbered 14 officers and 220 men. (Other estimates put Wilson’s force at closer to 400 effectives; however, those estimates may have included Company G, which was posted not in the camp but at nearby Battery Lincoln. Moreover, the regiment’s ranks had been thinned somewhat by sickness caused by bad water and the hot Florida sun.)

Anderson ordered his selected detachments of troops to assemble at the naval shipyard on the evening of October 8. There, they embarked aboard the wood-burning steamer Time for the short ride to Pensacola. While en route, the troops were divided into three battalions. Anderson placed Colonel James R. Chalmers of the 9th Mississippi Regiment in command of the first battalion, 350 strong. The second battalion, numbering 400 soldiers, was placed under the command of Colonel J. Patton Anderson of the 1st Regiment of Florida Volunteers. Colonel John K. Jackson, 5th Regiment Georgia Volunteers, assumed command of the 260-man third battalion. An independent company of 53 men under Lieutenant James H. Hallonquist, lightly armed with pistols and knives, was equipped for spiking cannons and burning enemy structures. In addition, a detail of medical officers and support personnel accompanied the expedition.

Upon arrival at Pensacola at 10 p.m., Anderson transferred a portion of his force to the steamer Ewing and several barges so that the troops could be landed more quickly on Santa Rosa Island. A third steamer, Neaffie, was requisitioned to assist with the barges. Shortly after midnight on October 9, the flotilla departed for Santa Rosa Island. The harbor crossing was swift and uneventful, and the troops landed at about 2 a.m. on a secluded beach roughly four miles east of Fort Pickens.

Once ashore, the battalions mustered around their respective commanders, and Anderson set his plan in motion. He directed Chalmers to advance westward along the northern shore of the island. Patton Anderson’s battalion was to cross the narrow strip of the island and turn westward along its southern Gulf shore. Jackson was instructed to follow in the rear of Chalmers’ battalion. At the first sign of contact with the enemy, he was to move to the center of the island and deploy his battalion as a link between the other two. Hallonquist followed in the rear of Jackson’s column. Anderson hoped to locate and rout Wilson’s Zouaves, overrun their cantonment and destroy the fortified batteries that lay between the cantonment and Fort Pickens. There is no indication that the general’s plan called for any offensive action against the fort itself.

The long march in the darkness over shifting sand dunes peppered with prickly pear cactus and sand spurs was toilsome and fatiguing for the soldiers. Still, the three Southern columns moved quickly and quietly; the element of surprise was critical to the success of the mission. To enable themselves to distinguish friend from foe in the darkness, the Confederates tied strips of white cloth around their left arms.

At about 3:30 a.m., scouts from Chalmers’ column were fired upon by a lone Zouave sentinel. The shot went wild, and the sentry was quickly dispatched; but the alarm had been sounded. Wilson hastened to form his command on the parade ground in front of the camp hospital. Guards informed him that about 2,000 armed men in two columns were marching upon us; that the pickets were all attacked about the same time. Wilson immediately sent his orderly to Fort Pickens to inform Brown of his situation.

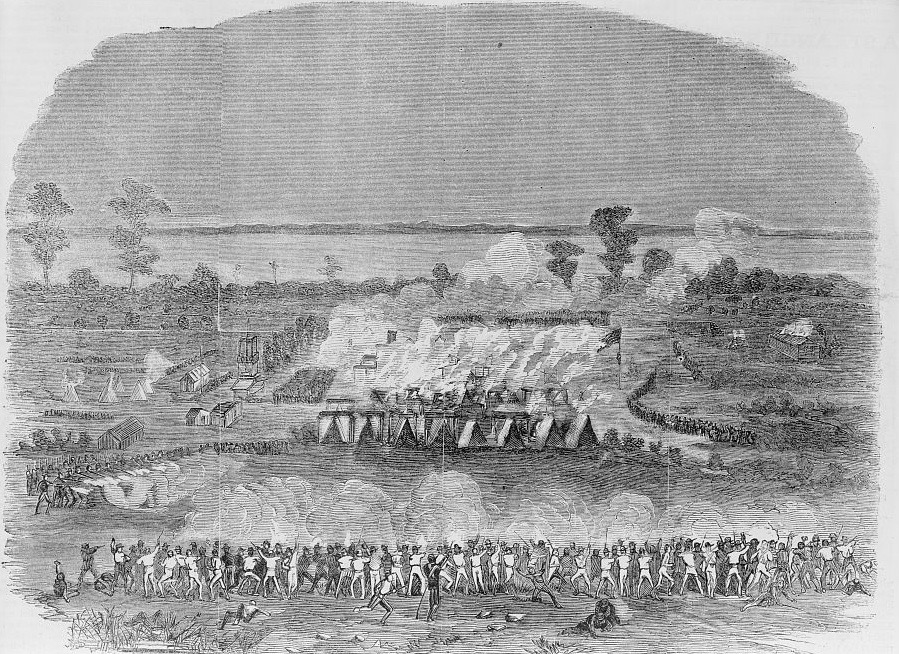

The sound of gunfire was Jackson’s cue to advance toward the center of the island. He ordered his men to fix bayonets and led them forward, sweeping aside the Federal pickets. They arrived at the Zouave cantonment, dubbed Camp Brown by the Federals, ahead of the other two battalions. The Zouaves were taken completely by surprise in their tents. The sight of Jackson’s charging troops was too much for the ill-trained volunteers to bear. They wavered under the heavy fire and fled toward Batteries Totten and Lincoln. Wilson did his best to rally his panic-stricken men but was unable to check their flight. Elated at their easy triumph, the Rebels stopped to plunder the evacuated camp. In doing so, however, they lost the precious momentum they needed to complete their victory.

It was not long before the battalions of Chalmers and Patton Anderson joined in the pillage of Camp Brown. The camp was thoroughly looted, and a great deal of property was stolen or destroyed. By 4 a.m., Hallonquist’s men had spiked a number of cannons and set the camp ablaze. Amid the chaos, General Anderson reassembled his troops. He quickly realized, however, that his plan of attacking the Federal batteries near the fort was impractical. Dawn was near, and the Federals were alert and ready. In the morning light his steamers would be easy targets for the Union gunboats in the bay. There simply was not enough time to mount a successful assault. Anderson therefore abandoned his original plan and issued orders for a full and orderly retreat back to the steamers.

Meanwhile, at Fort Pickens, Brown sounded the alarm and readied his garrison to repel the invaders. After ensuring that the ramparts were manned, he ordered Major Israel Vogdes to take two companies of regulars, about 100 men, to the relieve the 6th New York. Vogdes was reinforced en route by Company G of that regiment (which had been posted at Battery Lincoln), and the troops advanced along the beach of the north shore. He sent the New Yorkers ahead as skirmishers, with orders to protect the right flank of his column. In the pre-dawn darkness, however, the men of Company G somehow got lost amid the sand dunes and were not seen again for the duration of the encounter.

Vogdes and his regulars continued their march east along the beach in search of the Confederates. At a point just east of Camp Brown, a large force of Confederates, moving east in retreat, hit the column from the right and rear. In the darkness, the Union detachment had unwittingly marched past the attacking Confederate battalions. Now Vogdes was blocking their withdrawal.

Vogdes quickly realized his predicament. He was cut off from the fort and greatly outnumbered. He swung his detachment to the right and attempted to advance. Withering Confederate fire forced the Federals to fall back toward the Gulf side of the island, and in the process Vogdes was captured. His detachment, now under the command of Captain John Hildt, took up positions behind the dunes and fought to hold the Confederates back. After a sharp skirmish, the Federals were pushed aside, and the Southerners’ escape route was again open. Hildt continued his withdrawal to the south shore of the island. Along the way, he captured the Confederate medical detail left behind to care for the wounded.

At about 5 a.m., Brown ordered an infantry company and artillery battery under Major Lewis G. Arnold to march to the support of Vogdes. Arnold, upon learning of Vogdes’ capture, rallied Hildt’s men and directed a rapid pursuit of the fleeing Confederates. In their hasty retreat, the Rebels soon found themselves outflanked and harassed by Arnold’s riflemen. As the Confederates boarded the waiting steamers and barges, the Yankees fired on them from behind the closest dunes with considerable effect. General Anderson, shot through the left elbow, was among those wounded. The Rebel soldiers, crowded on the decks of their transports, returned the fire. After some delay, caused by a fouled screw on Neaffie, the flotilla pulled out of range of Arnold’s rifles and returned to Pensacola.

Florida’s first major land battle of the Civil War was over. Both sides claimed victory, and accounts of the battle and its resulting casualties varied. General Anderson viewed his expedition as a complete success. He commended the alacrity, courage and discipline of his men and reported his losses as 18 killed, 39 wounded and 30 captured. He estimated enemy losses at 50 to 60 killed and about 100 wounded.

Bragg, for his part, believed the enemy had been properly chastised for burning Judah. He also reported his expedition as entirely successful and, like Anderson, believed the enemy losses were much heavier than his own. He commended the troops and their commanders for their gallantry under such arduous circumstances. Bragg observed that 11 of the 13 Confederate dead recovered from the field had bullet wounds in the head, in addition to body wounds, which led him to infer that the disabled men had been executed.

In his report, Brown listed Federal casualties at 14 dead, 29 wounded and 24 captured. He was harshly critical of the conduct of the 6th New York troops, charging that they disgracefully ran and took shelter under our batteries. Regimental historian Gouverneur Morris viewed the matter in an entirely different light. In Morris’ biased and mostly inaccurate account of the engagement, Anderson’s force was numbered at 2,500 crack troops. Morris claimed that the 6th did not wildly flee their camp but fell back in good order…firing steadily, and that, contrary to reports, the regiment had not been stampeded or broken. He wrote that the 6th pursued the fleeing Rebels. Morris also exaggerated the number of Confederate dead at 400 and declared that the 6th New York had won a tidy victory. Colonel Wilson, in a similar exaggeration, reported 500 enemy soldiers had been killed or wounded.

In his vainglorious account, Morris was highly critical of Brown, blaming him for not preparing for the possibility of Bragg’s attack. He believed Brown was the only officer on Santa Rosa Island who did not recognize the almost certain probability of such an attack. Furthermore, Morris contended, Brown did not entrench the 6th, did not have their field battery organized, did not rise to the situation as it unfolded and did not properly press the pursuit.

The Battle of Santa Rosa Island resulted in no strategic gain for the Confederates, but Bragg felt that it gave his men confidence, raised their morale and made them stronger. The raid was also significant in that Anderson had been able to transport a large body of infantry across the bay and advance them to within close range of the fort without being detected. A Yankee regiment was scattered, and a camp was burned. Indeed, Anderson’s success begs the question of whether a larger force, supported by artillery, could not have accomplished the same feat and then gone on to seize Fort Pickens. In any case, the raid alerted the Federals to the danger, and the Southerners lost the element of surprise. Confederates never again assaulted Santa Rosa Island or Fort Pickens.

The Federal invasion of Tennessee in early 1862 caused the Confederates to withdraw from Pensacola. On May 9, the last Confederates to leave set fire to the naval shipyard and other military installations. On May 10, acting Mayor John Brosnaham surrendered the city to Union Lieutenant Richard Jackson. For the remainder of the war, Pensacola was in Union hands. The Federal Western Gulf Squadron used the shipyard as a base of operations, and Fort Barrancas provided a starting point for numerous Union raids and expeditions into Alabama and western Florida. One such expedition led to the Battle of Fort Hodgson.

The Battle of Fort Hodgson is also known as the Battle of 15-Mile Station, the Battle of Cantonment and the Battle of Camp Gonzalez. On July 21, 1864, a Federal force of 1,100 men departed their base at Fort Barrancas under the command of Brig. Gen. Alexander Asboth. Their orders were to march north in support of a raiding party dispatched by Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman. Sherman’s powerful army was closing in on Atlanta, and he planned to send Maj. Gen. Lovell H. Rousseau with 3,000 horsemen to destroy the railroad network that linked the Atlanta defenders with Confederate supply and munitions depots in central Alabama. Their mission complete, the raiders were to rejoin Sherman’s army near Atlanta. If they found it impossible to return to Atlanta, they were to head south toward the Union enclave of Pensacola. Asboth was directed to look out for Rousseau between July 20 and 25 and assist him as needed.

Asboth received Sherman’s directives on July 20 through a letter from his superior, Maj. Gen. Edward R.S. Canby, military director of West Mississippi, headquartered in New Orleans. Asboth immediately organized a strong task force, consisting of two combat teams. The first team, commanded by Colonel William C. Holbrook, was made up of four companies of the 7th Vermont Veteran Volunteers, 82nd Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry, and six companies of the 86th Regiment, U.S. Colored Infantry. The other team, commanded by Colonel Eugene von Kielmansegge, included four unmounted companies of the 1st Florida Cavalry, one section of the 1st Florida Battery, and Company M of the 14th New York Cavalry.

The teams departed Pensacola on July 21 in two separate columns. They rendezvoused north of the city and took the road running parallel to the Alabama & Florida Railroad. By the following morning, Asboth’s task force had reached 15-Mile Station. There they encountered an outpost of Confederates who greeted them with musket fire. Union skirmishers returned fire, and before long the Rebel pickets retreated toward their main camp. Asboth then deployed his entire force for an attack. Directly in front of the enemy camp, Holbrook’s 7th Vermont and 82nd U.S. Colored troops formed a double battle line, with four companies in reserve. The 86th U.S. Colored was also held in reserve. On the crest of a hill near the road, the 1st Florida Battery was posted. Kielmansegge formed his troops into a single line on Holbrook’s left flank. When preparations were completed, Asboth gave the signal to advance.

In the Confederate encampment, three companies of the 7th Alabama Cavalry, 360 strong, under the command of Colonel Joseph Hodgson, braced for Asboth’s attack. Through overwhelming strength of numbers, the Federals quickly drove the Rebels from their camp. Fortunately for the Confederates, Hodgson, in anticipation of an enemy advance, had ordered the construction of a wood and earthen fort about a mile north of his main camp. The fort, dubbed Fort Hodgson in his honor, had been completed on the afternoon of July 21. The Confederates fled to this new fort and delivered a vigorous fire on the Federals, whose advance was temporarily halted.

With the Confederates safely sheltered in their fort, Asboth called for artillery support. Following a bombardment from the two guns of the 1st Florida Battery, the Union infantry surged up the hill toward the fort. After about half an hour of fighting, Hodgson realized that his position was untenable. Fearing that his outnumbered horsemen would be killed or captured if they continued the fight, he ordered a hasty retreat. Asboth, with only a single company of cavalry, was unable to pursue the Confederate troopers in earnest. The chase was abandoned after three miles, and the Federals returned to the captured fort.

Asboth reported that only one of his men, from the 82nd, had been wounded in the day’s action. From local farmers he learned that the Rebels had retreated toward Pollard, Ala., with more than 30 wounded, leaving behind one mortally wounded trooper, whom Asboth left at a nearby farmhouse. Seven Alabamians were captured, one lieutenant and six troopers. The Federals also captured Hodgson’s official papers and muster rolls, a large red battle flag with 13 stars, a considerable amount of commissary and quartermaster stores, 17 horses with equipment, 18 sabers, 23 guns, ammunition and 23 head of cattle. The victors dined happily that evening on Rebel beef. The next morning, Fort Hodgson and the encampment were burned, along with the captured stores.

From questioning a captured 7th Alabama private, Asboth learned that Rousseau’s cavalry detachment had fought and won three battles with the Confederates in Alabama, successfully completed their mission and safely returned to Sherman’s army near Atlanta. The information would prove to be accurate. Asboth was disappointed that he would not get the chance to assist Rousseau; his services were no longer required. Nonetheless, he elected to proceed north to Pollard, Ala., and later that day fought a second skirmish with the 7th Alabama Cavalry. On July 24, however, Asboth received word that a Confederate cavalry force of 1,300 men, including a light battery of six guns, was riding hard from Mobile to intercept him. With no official purpose at hand — and no desire to face a superior force of cavalry — Asboth turned south and headed for Pensacola. His task force returned to quarters at Fort Barrancas on July 25. The troops had marched 72 miles in four days, suffering only a single combat casualty.

The Battle of Fort Hodgson was a decisive victory for Asboth, but it was by no means a major event. In comparison to the great battles of the Civil War, it was little more than a footnote in history. Neither the Union nor the Confederacy gained a strategic advantage or benefited militarily from the engagement. By the middle of 1864, the outcome of the war was in little doubt. The two main Confederate armies in the field were on the run. The Federals controlled the Mississippi River and exercised complete dominance of the seas. The Battle of Fort Hodgson was significant only in that it illustrated the Confederacy’s inability to protect itself from even minor incursions at this late stage of the war. Due to dwindling manpower and materiel resources, the Confederacy could not prevent Union forces from establishing footholds on its shores and operating with impunity in its territory.

Pensacola, deep in the heart of the South, remained in Federal hands for the last three years of the war. Fort Pickens, the key to the city’s shipyard and harbor, flew the Stars and Stripes throughout the entire conflict. In a way, the city never completely left the Union; and its early return to Federal jurisdiction foreshadowed the inevitable fate of the overall Confederate cause.

This article was written by Gary Rice and originally appeared in the January 1998 issue of America’s Civil War magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to America’s Civil War magazine today!