July 1863 was an extraordinarily bloody and decisive month, beginning with a three-day confrontation between General Robert E. Lee’s Army of Northern Virginia and Maj. Gen. George G. Meade’s Army of the Potomac around the Pennsylvania town of Gettysburg. On the 4th, the Confederates suffered defeat at Helena, Ark., and, more important, surrendered the essential Mississippi River stronghold of Vicksburg. For four days in the middle of the month, violence erupted in New York City, where rioters protesting the draft—incited primarily by Irish immigrants—began a melee that morphed into murderous attacks against the city’s black population. On the 18th, a valiant but poorly coordinated Union attack on Fort Wagner outside Charleston, S.C., demonstrated on a grand scale the courage of black soldiers under fire. The 54th Massachusetts Infantry’s opening assault that day bore a grisly 121 casualties—54 known dead. All of these events were tipping points of some sort, and another—in the scrubby hill country of what is now Oklahoma—cannot be overlooked. On July 17, 1863, the fate of Indian Territory was being decided at a stagecoach stop known as Honey Springs.

BETWEEN 1831 AND 1850, members of what were known as the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, and Seminole) had been driven west from their homes in the American Southeast to settle in what the U.S. government designated “Indian Territory.” They, too, would be divided during the Civil War. Within the tribes, some subgroups remained loyal to the Union while the majority embraced the Confederate cause for various cultural or economic reasons. A good many Cherokee, for example, were slaveowners.

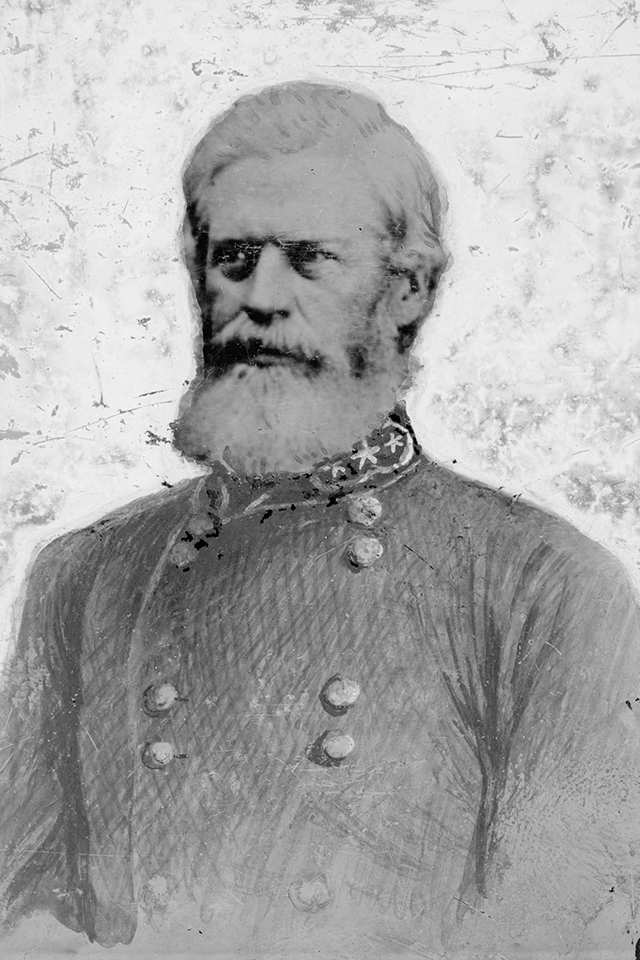

A key figure during this turbulent period was Douglas Hancock Cooper, a Mississippi-born Mexican War veteran who earned the trust and respect of many tribesmen as an agent to the Chickasaw. When war broke out in 1861 and Cooper took a rebel stand, Confederate Secretary of War Leroy Pope Walker ordered him to “take measures to secure the protection of these tribes in their present country from the agrarian rapacity of the north.” Parlaying his popularity into widespread allegiance, Cooper formed the 1,400 man-strong 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw Mounted Rifles.

As Cooper and another pro-South agent, Albert Pike, arranged alliances between Confederate authorities and the Civilized Tribes, Federal forces were being withdrawn from Indian Territory, and the frontier as a whole, to deal with the burgeoning conflict in the East. Cooper quickly joined with Texas and Arkansas troops under Colonel James McQueen McIntosh to win a succession of victories. The final one, at Chustenahlah on December 26, 1861, forced some 9,000 pro-Union Indians to seek succor at Fort Row, Kan. Nearly 2,000 would perish in this new exodus, which came to be called the Trail of Blood on Ice.

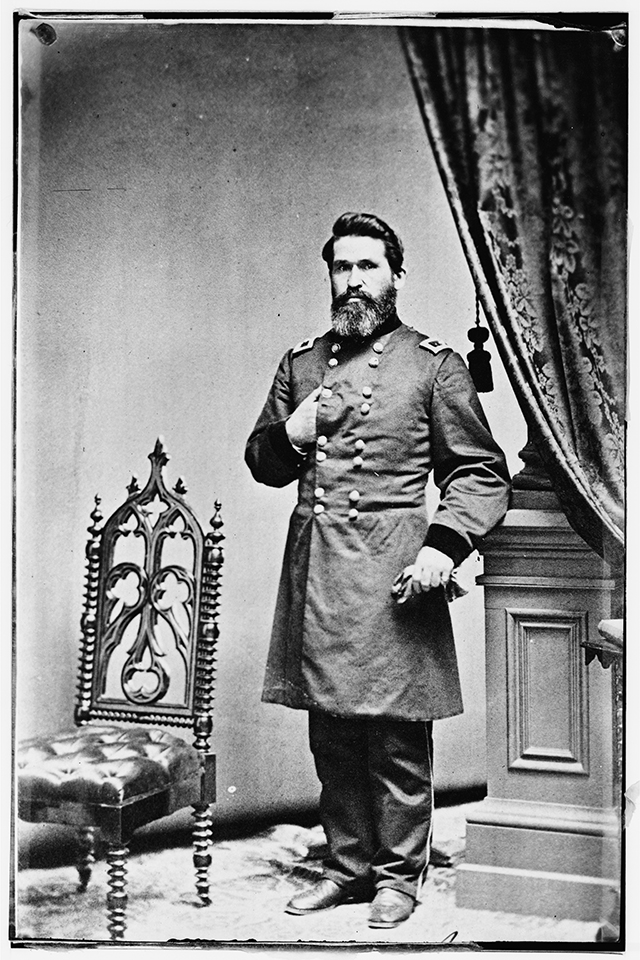

Until June 1862, Confederate control of Indian Territory went virtually unchallenged. That would change with the arrival of Union officer James Gilpatrick Blunt. A staunch Republican abolitionist, Blunt had moved to Kansas in 1856, fighting alongside John Brown and eventually serving on the committee drafting the state constitution. At the Civil War’s outset, Lt. Col. Blunt led the 2nd Kansas Volunteers, but on April 18, 1862, he was made a brigadier general commanding the Department of Kansas.

The Cherokee, Creek, and Seminole units under Blunt’s command convinced him of the importance of earning Indian loyalty. Of the three Indian regiments he organized, most of the 1,200 men in the 3rd Indian Home Guard were Cherokee who had defected from the Confederate side.

In late June 1862, Blunt launched an offensive that took the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah on July 10, but soon petered out because of overstretched supply lines and the incompetence of the expedition’s commander, Colonel William Weer. Later that summer, Albert Pike, now a brigadier, was instructed to lead an offensive in Missouri. Judging his forces and logistics insufficient, Pike tendered his resignation. On September 30, his replacement, Cooper, won a victory at Newtonia.

A subsequent series of setbacks, however, compelled Cooper to withdraw south of the Arkansas River. In January 1863, inexperienced Brig. Gen. William Steele assumed command of Rebel forces in the region, but he wisely stayed put at his Fort Smith headquarters, leaving Cooper as Indian Territory’s de facto leader.

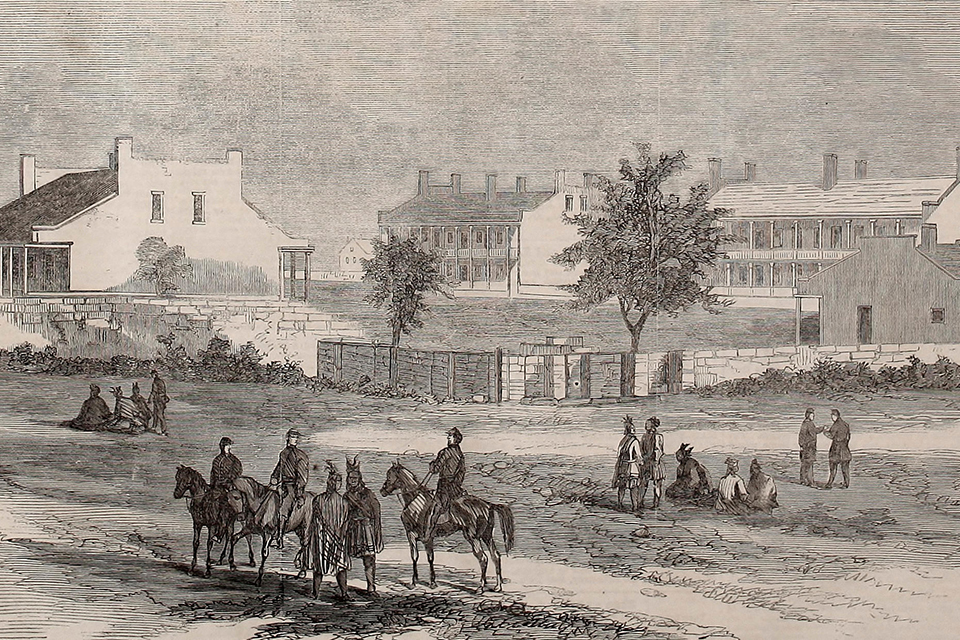

When a Union force under Colonel William A. Phillips reoccupied Fort Gibson in April, Cooper responded by concentrating about 6,000 men at Honey Springs, roughly 20 miles southwest of the fort. Located along the Texas Road—the main transportation route connecting Indian Territory with Texas, Kansas, Missouri, and Arkansas—the stage depot and provision point at Honey Springs consisted of a frame commissary building, a log hospital, several arbors, and a row of tents. The local springs that inspired its name provided ample water for horses and livestock.

Phillips had a key disadvantage in having to rely on a 175-mile-long supply line from Fort Scott in Kansas, and both Fort Gibson and the supply trains that sustained it suffered constant harassment from Rebel mounted detachments. In addition, a 3,000-man Confederate brigade under Brig. Gen. William Lewis Cabell at Fort Smith was poised to march north if needed.

Blunt, meanwhile, was also engaged in a political struggle in Kansas. Though Blunt had Senator James H. Lane’s support, Governor Thomas Carney and Maj. Gen. John A. Schofield, commanding the Army of the Frontier, detested him. A U.S. Military Academy graduate, Scho-field bore great contempt for what he considered rash gambling by the non-West Point doctor-turned-general.

Blunt, in turn, believed that Schofield was too cautious, referring to his headquarters as the “hind quarters of the department.”

Even after Blunt was promoted to major general, Schofield split the Department of Kansas into the District of the Border under Brig. Gen. Thomas Ewing and the District of the Frontier under Blunt, who grumbled that his command was “reduced in proportion as my rank was increased.” Only Lane’s influence canceled out the efforts of Carney, Schofield, and Ewing to have Blunt removed entirely.

By June 1863, Blunt and his officers decided that a bold move leading to a convincing victory was the only way Blunt could reverse his flagging fortunes. He gathered his forces to attack Cooper’s Confederates before they could consolidate their overwhelming numbers and strike first.

In late June, a 300-wagon Union supply train, as well as reinforcements from units such as the 2nd Colorado Infantry and the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry, set out from Fort Scott. By the time the train reached Cabin Creek on July 1, its commander, Colonel James M. Williams, had learned from captured Rebels that 1,600–1,800 Indians under Colonel Stand Watie awaited him in rifle pits on the other side of the creek.

The creek had swollen above shoulder height, so Williams corralled his force and prepared for a crossing the next morning. The Federals opened with a half-hour artillery bombardment followed by a charge by the 3rd Indian Home Guard that was thrown back. Williams ordered forward the 9th Kansas Cavalry, whose troopers managed to gain a bridgehead. Williams then personally led his regiment, the 1st Kansas Infantry (Colored), in a headlong charge across the creek and into the brush.

Watie had 65 killed; Union casualties ranged from three to 23. Williams promptly resumed his trek to Fort Gibson.

Cooper, now a brigadier general, began making plans to retake Fort Gibson as soon as he could be joined by Cabell’s 3,000-man brigade from Fort Smith, expected to arrive by July 17. For Phillips, who learned of Cooper’s intentions from Union spies and Confederate deserters, help was on the way, however. Faced with the prospect of pitting his 3,000 troops against 6,000 Rebels, with another 3,000 about to join them, Blunt resolved that the best defense would be a good offense. He left Fort Scott headed for Fort Gibson on July 5.

Blunt became ill during the excursion, possibly from malaria. But on July 15, though suffering from what he called “burning fever” and recurring chills, Blunt oversaw completion of flatboats to transport his men across the Arkansas River and issued six-day rations.

At midnight on the 16th, Blunt led 250 6th Kansas Cavalry troopers, as well as four artillery pieces, toward the swollen river. At a ford 13 miles down the road, Blunt’s vanguard encountered 100 Confederate pickets, driving them away with artillery. The Union commander then turned downstream to the mouth of the Grand River, a tributary of the Arkansas River, and had his force cross on the flatboats. Several men drowned in the process.

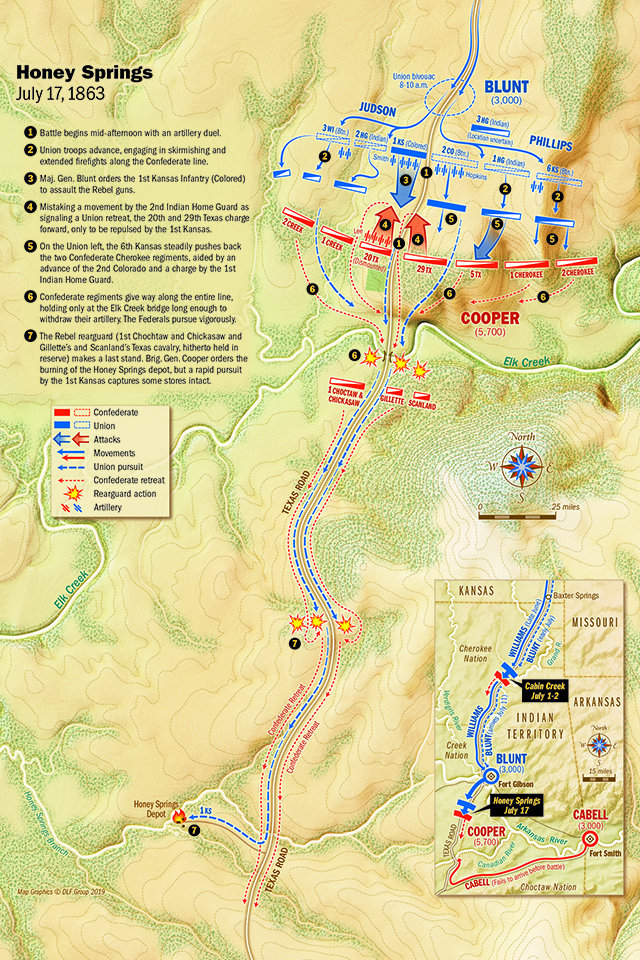

Despite his malady, Blunt spent 24 hours in the saddle, with only a four-hour rest period. At 4 a.m. on July 17, amid pouring rain, the Union troops broke camp and advanced down the Texas Road. Near Chimney Mountain, Company F of the 6th Kansas Cavalry skirmished with enemy scouts. Five miles north of Elk Creek, the company was attacked by Colonel Tandy Walker’s 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment and Captain L.E. Gillette’s Texas Squadron, forcing Blunt to commit the rest of the 6th Kansas to the vanguard’s aid to drive the Rebels back to Honey Springs.

Walker soon realized that the cheap grade of Mexican gunpowder his men were using readily absorbed moisture, degrading its effectiveness—a handicap on top of the Confederates’ general shortage of up-to-date weaponry. For example, compared to the mixed bag of hunting rifles, smoothbores, and shotguns the Confederates carried, the 1st Kansas was equipped primarily with Springfield M-1842 muskets that fired buck and ball (i.e., cartridges combining a .69-caliber round ball with three buckshot).

While reconnoitering near Honey Springs, Blunt and his staff spotted enemy soldiers forming in a shallow crescent-shaped battle line in the woods that lined the Texas Road. Suspecting an ambush rather than a pitched fight, Blunt’s chief of staff, Lt. Col. Thomas Moonlight, reckoned “the enemy never for a moment supposed that we were anything more than the cavalry and artillery force which had driven him from his entrenchments the day before.”

At 10 a.m., after breakfast and a brief rest period, Blunt formed two columns, hoping to conceal his numbers for as long as possible. He then marched his troops to within a quarter-mile of the Confederates before rapidly deploying them into line. The 1st Brigade on the Union right, under Colonel William R. Judson, included the 2nd Indian Home Guard, the 1st Kansas Infantry, and six companies of the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry. On the left, Phillips’ 2nd Brigade had six companies of the 2nd Colorado Infantry, the 1st Indian Home Guard, and detachments of the 6th Kansas Cavalry. In support were six 12-pounder Napoleons, four 12-pounder mountain howitzers, and two 6-pounder steel howitzers of the 2nd and 3rd Kansas Light Artillery.

Cooper’s line consisted of the 1st and 2nd Cherokee Mounted Rifles on the right, the 1st and 2nd Creek regiments on the left, and Colonel Thomas Bass’ Texas Brigade (20th Texas Cavalry, Dismounted; 29th Texas Cavalry; and 5th Texas Partisan Rangers) at center. Just left of the Texas Road was Captain Roswell W. Lee’s four-gun battery.

Cooper’s force straddling the Texas Road, concealed behind trees and brush upon undulating terrain, totaled about 5,700, as he had sent Watie’s Cherokee Regiment to Webber’s Falls, hoping for a diversion. The gambit served only to keep Watie’s 300 crack troops out of the coming battle, and Cooper further canceled any supposed numerical edge he had by holding the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw regiment and two squadrons of Texas cavalry in reserve.

The battle began at midafternoon when Blunt sent out skirmishers from his line and Phillips ordered Captain Henry Hopkins’ battery of the 3rd Kansas to open fire. Lee’s Battery—consisting of three 12-pounder mountain howitzers and an experimental 2¼-inch bronze mountain rifle, one of only 18 produced at the Tredegar Iron Works in Richmond, Va.—promptly returned fire.

The Texans drew first blood in the duel, with a direct hit on one of Hopkins’ Napoleons, killing or wounding six gunners and four horses. In response, two of Hopkins’ guns hit a Rebel howitzer, killing or wounding all its men and horses. The superior range and accuracy of the Confederates’ 2¼-inch howitzer was put to good use against the Union officers on high ground beyond the main battle line, its shells killing one of Blunt’s aides and narrowly missing Captain Edward A. Smith of the 2nd Kansas Battery.

Despite another rain squall that further dampened their gunpowder, the 1st and 2nd Cherokee held their own during a general dismounted assault by the 6th Kansas Cavalry. Cooper bolstered his right flank with reinforcements from the 20th Texas and the 2nd Choctaw and Chickasaw, then returned to the center to survey the Union line and realized that it was “larger than reported…and larger than I supposed they would bring from Gibson.”

As fighting on the Union left raged hand to hand, Blunt ordered Smith’s battery to deploy to the left and ordered Williams to “move your regiment to the front and support this battery” and to take the Confederate guns “if the opportunity offers.” Williams ordered “fix bayonets” and led the 1st Kansas forward. Advancing on the regiment’s immediate left was the 2nd Colorado, and elements of the 3rd Wisconsin Cavalry worked toward finding a way around the Rebels’ left flank.

Like Blunt, Williams was an abolitionist and made sure his black troops knew full well they were engaged in what he considered a “holy war” and offered reminders of the so-called “Sherwood Massacre” on May 18, 1863, when guerrillas led by Thomas Livingston overwhelmed and promptly murdered a 16-man 1st Kansas foraging party in Sherwood, Mo. “Show the enemy this day that you are not asking for quarter, and that you know how and are eager to fight for your freedom,” Williams declared. “[K]eep cool and do not fire until you receive the order, and then aim deliberately below the waist belt.”

Since its formation in August 1862, the 1st Kansas—most of whose men were escaped slaves from Arkansas, Missouri, and Indian Territory—had drilled zealously and first put their training to good use in a skirmish at Island Mound, Mo., on October 29, 1862. Besides the regiment’s exemplary motivation and discipline, one of Blunt’s officers noted that with the locally savvy 1st Kansas “we had men who knew every highway, byway and hiding place and also all the men whether rebel or Union men.”

At Honey Springs, Williams led his regiment to within 40 paces of the 29th Texas before ordering it to fire. The Texans fired at the same moment, however, severely wounding Williams. In the exchange, the 29th’s commander, Colonel Charles DeMorse, was wounded in the hand.

Williams’ deputy, Lt. Col. John Bowles, took charge and ordered the 1st Kansas to reload and fire from a prone position. Meanwhile, to its right, the 2nd Colorado’s marksmen “killed a great number, and not a man was found but was not shot in the head or neck.”

What would be the battle’s turning point began when the Federals’ 2nd Indian Home Guard unintentionally strayed between the 1st Kansas and the two Texas regiments. When Bowles shouted for the Indians to withdraw to the Federal line, the Texans overheard him and assumed the Yankees were falling back and mounted a charge in hopes a minor breach could be turned into a general rout.

Although aware of their deficient powder situation, the Texans were confident an onrush of Lone Star State steel would convince the 1st Kansas’ black soldiers to drop their weapons and run. They were wrong. The 1st Kansas stood fast until the Rebels were within 25 paces, then Bowles gave the order and nearly 700 M-1842 rifle-muskets cut a deadly swath through the assailants. The Texan regimental colors

fell, only to be snatched up by another soldier, who in turn went down when the well-drilled and disciplined black soldiers swiftly reloaded and fired again. When a third Texan raised the banner anew, another volley cut him down. At that point the Confederates had enough and withdrew, allowing the 2nd Indian Home Guard to counterattack and be the unit to seize the fallen colors—to the 1st Kansas’ chagrin.

Cooper noted that the Indians were “wet and disheartened by finding their guns almost useless,” which soon produced what Dallas W. Bowman of the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw admitted was a “general stampede.” Judging his position north of Elk Creek untenable, Cooper ordered the bridge held until he could get his surviving artillery and troops across. With Union forces in continuous pursuit, the Confederates maintained some cohesion for 1½ miles until they reached the Honey Springs Depot.

While the 1st Choctaw and Chickasaw and the Texas cavalry squadrons made a stand, Cooper sent away the artillery and baggage trains and had the depot’s buildings and extra supplies set on fire. The 1st Kansas arrived in time to put out some fires and recover stores of bacon, dried beef, flour, sorghum, and salt. The Rebels also left behind a reminder of what was at stake: 500 pairs of iron shackles.

The four-hour Battle of Honey Springs ended at 2 p.m. when Blunt, still suffering an intense fever, called a halt, noting that his “horses and infantry were completely exhausted…” He bivouacked for the night while wounded soldiers were tended to and the dead—Union and Confederate alike—given proper burials. At 4 p.m., as his battered troops retreated eastward, Cooper came upon Cabell’s 3,000-man force from Fort Smith—too late to retake the battle’s initiative. Later the next day, Blunt led his force, victorious but low on ammunition, back to Fort Gibson.

Though Cooper reported he inflicted more than 200 casualties, with his own as 134 dead and wounded and 47 captured, Blunt recorded his losses as 17 killed and 60 wounded, and that he had buried 150 Confederates, taken 77 prisoners, and wounded an estimated 400. Cooper later sent a letter of appreciation to Blunt for his adversary’s decision to bury the Confederate dead the same as his own.

The state of Oklahoma (formed from Indian Territory in 1907) regards Honey Springs as the Gettysburg of the Trans-Mississippi Theater. Strategically, however, it might

have been more significant. Blunt’s victory did more than merely save his and Senator Lane’s political fortunes—it marked the end of organized fighting in Indian Territory. The loss of the depot and its supplies was disastrous for the Confederates, already operating on a logistical shoestring. They abandoned Fort Smith in August. From then on, their diminishing presence in the territory would belong primarily to mounted guerrilla units such as Watie’s Cherokees and William Quantrill’s raiders.

Of note is that Honey Springs was also the only major Civil War battle in which white soldiers were in the minority—on both sides. One day before the 54th Massachusetts became martyrs at Fort Wagner, the 1st Kansas was pivotal in Honey Springs’ outcome. In his official report, Blunt gave the regiment its due: “The First Kansas (Colored) particularly distinguished itself; they fought like veterans, and preserved their line unbroken throughout….Their coolness and bravery I have never seen surpassed; they were in the hottest of the fight, and opposed to Texas troops twice their number, whom they completely routed.”

The Honey Springs settlement vanished after the war under the growing Missouri, Kansas & Texas Railroad, but nearly 3,000 acres of the battlefield survives in McIntosh County, Okla. The battle flags of the 1st Kansas Infantry can still be seen at the Kansas state capitol in Topeka.

Jon Guttman is research director of America’s Civil War and other HistoryNet publications.