As usual, the odds were against the Royal Air Force. This time it was just one Heinkel bomber, but with an escort of 17 Messerschmitts, crossing the white cliffs of Dover before wheeling north toward the RAF base at Duxford.

Squadron Leader Ron Chadwick acquired them on ground-control radar, but could only send two fighters to intercept them. “We are expecting our foreign visitors in 10 minutes, Spitfire red leader,” he radioed. “Keep your eye open for them.”

“Spitfire red leader here. I have sighted our visitors.” The Spit pilot called his wingman, flying a Hawker Hurricane: “Remember, they don’t know we’re here. Let’s go in and surprise them.”

Outnumbered almost 10-to-1, the two Brits swept down on the black-crossed intruders…and pulled up in front of them, wagging wings in greeting. The “Luftwaffe” leader’s response on landing at Duxford has gone unrecorded, but it was in Spanish, not German. This wasn’t 1940; it was May 1968, and the Spits and ’Schmitts were to spend the summer filming the greatest World War II air combat epic of all: Battle of Britain.

A Man and a PLan

Producer Ben Fisz had flown Hurricanes for the RAF and Polish air force in the war. He pitched his concept as a British The Longest Day—the 1962 20th Century Fox D-Day movie—but in the air. “This will be the biggest picture ever made in Great Britain, and possibly the biggest in the world,” enthused Fisz.

But the idea of a big-budget air war epic with no Yanks in it almost never got off the ground. American studio bosses thought the initial script “awfully English” until James Bond producer Harry Saltzman brought director Guy Hamilton (Goldfinger) aboard. “What we want to do is show what it really was like,” Hamilton said. “How it was to be involved in aerial combat. The kind of timing and sheer animal ability it took.”

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

United Artists and virtually every big-name British actor of the day—among others, Sir Laurence Olivier, Michael Caine, Trevor Howard, Christopher Plummer and Robert Shaw—got on board (though not Sean Connery, then distancing himself from Saltzman and the Bond franchise). Securing the film’s other “stars” fell to former RAF Group Captain Thomas “Hamish” Mahaddie, veteran of Bomber Command’s Pathfinder Force and a film industry warbird wrangler. “Within 10 days I had found out that there were over 100 Spitfires still left in the world,” he said. “They were not all airworthy, but they had possibilities.”

Most were late-war models, with four-blade props, wing cannons, teardrop canopies, pointed rudders and clipped wingtips. They were altered to Battle of Britain–era Mk. I standards except for their Merlin and Griffon engines (note six exhausts per side instead of the correct three). Stunt doubles were built from the ground up, several with motorcycle engines enabling them to taxi before being blown up.

Hurricane Search

Hurricanes, which outnumbered Spitfires during the battle, had not fared so well after the war. The Ministry of Defence could supply just three, only one of which could fly. Manufacturer Hawker Siddeley provided another, and one was flown in from Canada, disassembled, aboard an RAF C-130. The sixth, a rare Sea Hurricane Ib, could taxi but tended to overheat in the air.

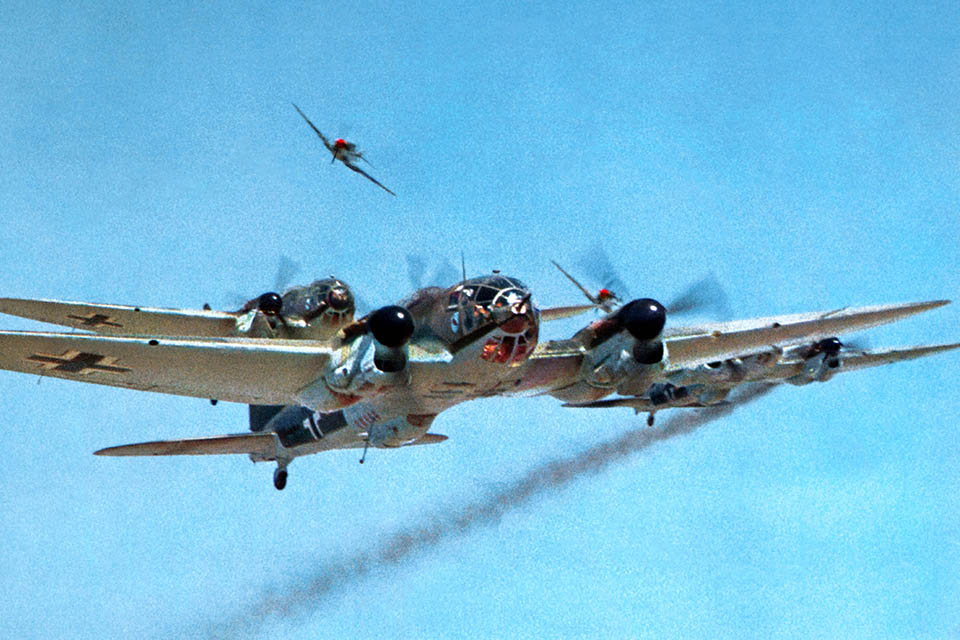

Finding German warbirds was even harder. No Junkers Ju-87s were available at all; the Stukas in the movie are all radio-controlled flying scale models. Former Luftwaffe Lt. Gen. Adolf Galland, a battle veteran who had joined the film company as technical adviser, told Mahaddie: “Why don’t you try Spain? Their bomber force is composed of Heinkel bombers, though they use Rolls-Royce Merlin engines in them nowadays instead of Mercedes-Benz. Their fighter force used to use Messerschmitts, too—with Merlin engines also—but I hear they’re scrapping them. They might let you buy them.”

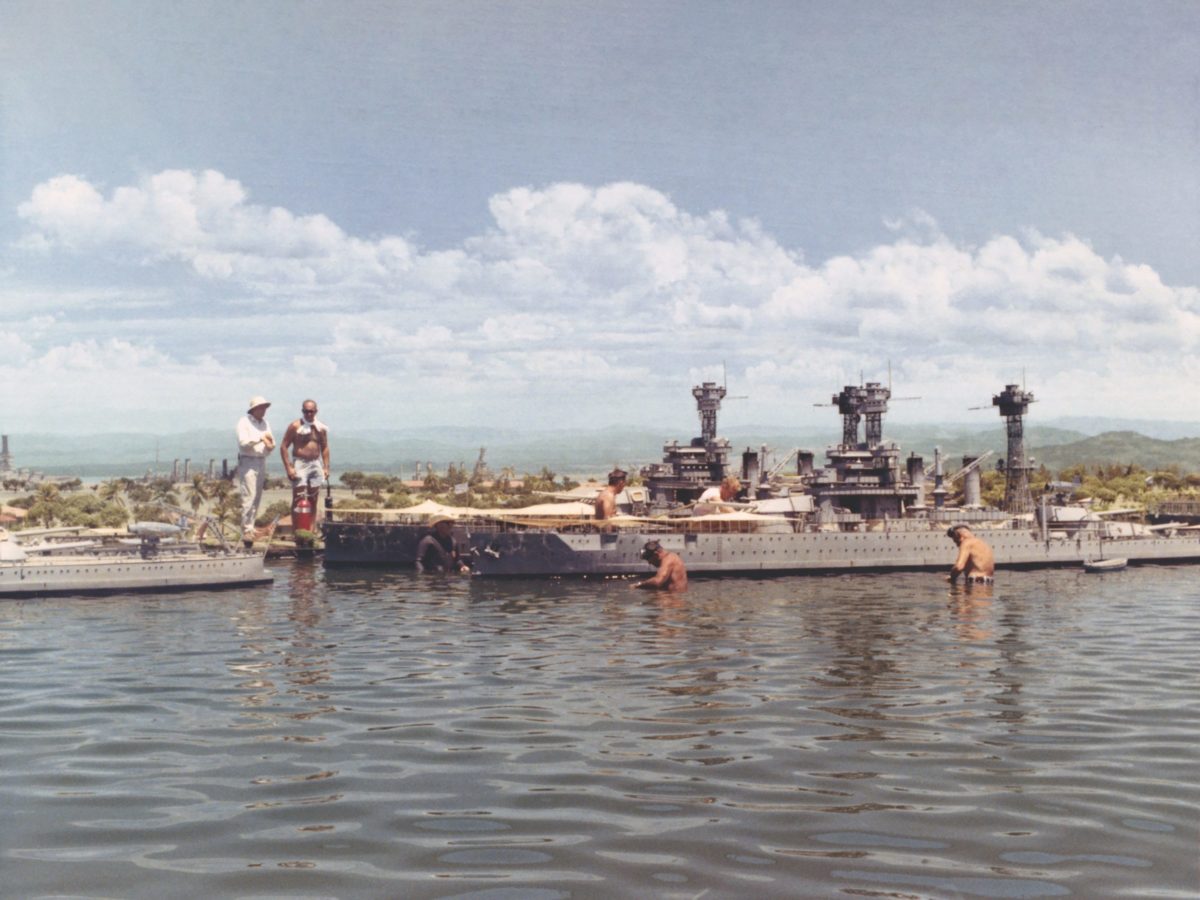

Flying to Tablada Airfield on the outskirts of Seville, Mahaddie found eight Hispano Aviación HA-1112 M1L Buchóns (essentially license-built, Merlin-powered Me-109Gs) being sold off by the Spanish air force, along with sufficient parts to build some 20 more. He bought the lot for $2,250 each. Representatives of the Confederate Air Force (today’s Commemorative Air Force) from Texas had purchased four Buchóns and agreed to loan them and the CAF’s Spitfires to the filmmakers on the condition they could fly them in the air combat scenes and play bit parts as Luftwaffe officers. Given aileron struts, squared wingtips and dummy guns fitted to the wings and engine cowls (but retaining the Merlin engines, hence their almost P-40ish nose scoops), the Buchóns were as close to battle-era Me-109E models as they could ever be.

Acquiring the Heinkels, however, was not a matter of money. Madrid’s CASA 2.111s—Merlin-powered Heinkel He-111s—were not for sale. Since the Spanish government was squabbling with Britain over Gibraltar, prospects of a bomber fleet for the movie were slim until Rolls-Royce threatened to withhold parts. Then Madrid agreed to lend the entire flotilla, with crews, free of charge, except for painting Luftwaffe camouflage and insignia and repainting in Spanish colors afterward.

Supporting Cast

Seville’s airfields stood in as Luftwaffe air bases when filming began in March 1968. As the Spanish countryside looked nothing like Kent, the bomber scenes were filmed out over the Atlantic. For a counterattacker, Fleet Air Arm veteran, aircraft restorer and replica builder Vivian Bellamy flew a Spitfire IX fitted with a long-range external tank via Bordeaux to Madrid. “I decided to show them what a Spitfire could do,” he recalled, “so when I took off I gave the aircraft 108 lbs of boost, and it literally shot into the sky, followed by a low flypast down the runway. As I was about to turn on course for Seville, the airfield control tower came on the radio and said ‘Would you do that again please.’”

A war surplus B-25, known as the “Psychedelic Monster” for its garish high-visibility paint scheme, served as camera plane. Aerial photographer John Jordan, who had lost a leg to a helicopter blade filming 1967’s You Only Live Twice, invented a “parashoot” to hang underneath a helicopter while aircraft whirled around him. (In 1970 he would die in a fall from a B-25 while filming Catch-22.) Future airshow commentator John Blake of the Royal Aero Club served as dogfight choreographer. “We used to fly a racetrack pattern with the Heinkels,” he recalled, “and the Messerschmitts were in the standard wartime finger four formation, but considerably closed up so that they would fit into the camera frame. We also used to get the filming sequences all lined up ready, and then a fleet of Spanish fishing trawlers would come into shot below us and we would have to go around again.”

And that was when they were able to fly at all. The rain in Spain, it seemed, fell mainly on the planes. One aerial shoot per day was par; two was lucky. Filming fell behind schedule. Costs began to mount, and tensions rose.

The Spanish insisted their Heinkels join a ceremonial NATO flypast, which meant, on top of time lost, stripping and then replacing their Luftwaffe markings at an estimated cost of £1,000 per aircraft. Director Hamilton put up such a fuss that it was agreed to leave the bombers in Nazi warpaint, which surely garnered double-takes from ex-Allied brass at the event. And with only a limited number of concrete dummy bombs made, their bomb-run scene had to be done in one take. According to Blake, “On the allotted bomb-dropping day we flew south, instead of flying our usual westerly direction. The Heinkels set off and actually headed in the direction of Gibraltar. At that time General [Francisco] Franco was having one of his tantrums about the British and Gibraltar, and I did actually wonder whether the Spanish pilots were going to drop the concrete bombs on Gibraltar! Thankfully they didn’t and the scenes were shot successfully.”

Veteran Pilots, Old grudges

Galland had flown with the Luftwaffe Condor Legion during the Spanish Civil War, but rejected the whole premise of a Battle of Britain. “We made a number of attacks against England between July and September,” he said. “Then we discovered that we were not achieving the desired effect, and so we retired.” But Hamilton, who had lived through the Blitz, served in the Royal Navy and survived the infamous decimation of Convoy PQ-17 by Luftwaffe bombers and U-boats, openly detested Germans. He ultimately threw Galland off the set.

English battle veterans had been named technical advisers too: Group Captains Douglas Bader and Peter Townsend, Wing Cmdr. Robert Stanford Tuck and Squadron Leaders James “Ginger” Lacey and Bill Foxley, who had suffered terrible burns in a 1944 Vickers Wellington crash. Although from quite different generations, the actors gained new respect for the WWII pilots. “I can remember listening in Canada, night after night, to Edward R. Murrow on the radio describing the progress of the battle,” Christopher Plummer said. “Now to meet these guys like Bader and Lacey and Townsend is really something.”

Airborne Movie Magic

The pilots were less impressed by the film stars. Shaw, taxiing a Spitfire, trod a little too hard on the brakes and stood it on its nose. And Lacey complained: “I’m having the devil’s time getting the actors to be authentic. I can’t get them to cut their hair. In those days, we were all close cropped, and these chaps look like bloody Beatles. They all say they dasn’t cut their hair; they’ll ruin their image.”

The pilots had cemented their image in the summer of 1940 and didn’t concern themselves now. Lacey even brushed off being awarded the Distinguished Flying Medal with Bar by no less than King George VI: “The king asked me what I’d got the medal for. I said I’d forgotten. Well then, he said, what about the bar? Well, I’d forgotten that too. He must have thought I’d come to pick up the medal for a pal of mine.”

Nor did they have much good to say about their old enemies turned Cold War allies. “It was quite a shock visiting Duxford air base today,” Bader told reporters. “That was my base during the war. I went out there today and saw all those Kraut airplanes, and I thought, what’s going on?”

“Well,” Lacey told him, “if it hadn’t been for the Battle of Britain they might really have been there.”

For the London bombing scene the studio bought an abandoned tea warehouse and demolished it, along with a derelict section of the city waterfront that had actually been heavily bombed in 1940 and, a generation later, condemned by the authorities. The hangar that gets blown up in the attack on Duxford really was a hangar at Duxford, and really was blown up, though it took two tries.

Rotten LUck

Unfortunately the bad weather followed the production to England, with similar effect on the flying schedule. “I was contracted for six weeks,” said CAF founder Wilson “Connie” Edwards, “and 11 months later I was still getting shot down—128 times, and that doesn’t count the practice runs. I could tell right quick I wasn’t gonna win the war.” (Edwards didn’t complain too loudly. In lieu of payment, he received 16 of the Buchóns, including a rare two-seat trainer. He traded two of them back for a Spitfire Mk. IX, and kept the rest at his ranch in Big Spring, Texas, until selling the last of them off in 2014.

Grounded by rain and forbidden to hit the pubs, the battle veterans loitered around the airfields and nursed old wounds. “I loathe those crooked swastikas,” Bader told reporters. “…When you saw one of them go up in smoke one was delighted and one never thought about anyone being inside them.” Asked for the moral of the movie story, he said, “Surely the lesson is that one forgives but that one doesn’t forget. It’s as simple as that.”

Bader had lost both legs in an aircraft crash, but famously hadn’t let that stop him from flying fighters. He demonstrated for reporters how a double amputee gets in and out of a Spitfire and then, on request, did the same in a Spanish Messerschmitt, but came away wiping his hands. “You know, even if I was blind, I’d know I’d been in a bloody Kraut kite,” he said. “You can tell by their smell!”

That Buchón had likely never seen Germany. Robert Shaw said aghast, “I never knew people talked like that.”

Galland, despite losing two younger brothers—also fighter aces—in the war, had personally seen to Bader’s good treatment after his capture, but received little thanks for it and now harbored something of a grudge. Yet as filming wound down Galland and Stanford Tuck took the tandem-seat 109 up for a flight together, and Stanford Tuck later became godfather to Galland’s son.

Bad Blood

Bad blood still simmered, however, between adherents of Air Chief Marshal Hugh Dowding and former No. 11 Group commander Keith Park on one side, and Bader and former 12 Group commander, the late Air Vice Marshal (later Air Chief Marshal Sir) Trafford Leigh-Mallory on the other. In the battle, Leigh-Mallory’s “Big Wing” strategy, depending on who tells the story, either failed to support Park’s 11 Group or was not supported by it. “We are going to break a few eggs,” director Hamilton had promised, “by showing for the first time some of the smelly things that were going on down below, in the Air Ministry, while the battle was being fought in the air.”

Park, in 1968 a city councilor in Auckland, New Zealand, had kept tabs on the production and disparaged it in the Kiwi press, especially when Rex Harrison, who had actually been one of his junior officers in 1940, withdrew from playing him. “There was a dirty little intrigue going on behind the scenes among Air Ministry staff and the group immediately to the rear of No. 11,” Park told reporters. “As a result of this intrigue, just after the Battle of Britain was won, the Air Ministry sacked Dowding, and I was sent off to a training command.”

Pilots had taken sides in 1940 and clung to them in 1968. To the consternation of Stanford Tuck, Lacey called Leigh-Mallory “a clot.” Matters came to a head when Dowding himself—then 86, wheelchair-bound, nearly blind and still bitter—visited the Battle of Britain set. He was rolled in to view rushes of the scene where Olivier, playing him, tells a stuffy air minister that Britain’s back is to the wall: “Our young men will have to shoot down their young men at the rate of four to one.” When the lights came up, production paused while the famously stoic air chief marshal wept.

Dowding was seen to coach Trevor Howard, playing Park, and afterward wrote his former group leader, “I hope I can relieve you of any apprehensions as to the treatment you will receive at the hands of the film company.” Battle of Britain doesn’t try to resolve the Big Wing controversy, but simply gives Dowding what he did not get during the war: credit for victory. “If it hadn’t been for him, old boy,” Bader admitted to Shaw, “we might be digging salt out of a Silesian salt mine,” and on second thought, “…I’d probably be dead, but your generation would.”

Crash and Burn

That fact flew over the heads of audiences and reviewers. “The aerial scenes are allowed to run forever and repeat themselves shamelessly, until we’re sure we saw that same Heinkel dive into the sea (sorry—the ‘drink’) three times already,” opined film critic Roger Ebert, clearly no aviation buff. After all the expense—and going up against late-’60s antiwar sentiment and cynicism—Battle of Britain not only failed to turn a profit, but lost $10 million globally.

Since then, however, video sales have more than made up the difference, and it remains a cult favorite. A long-running Hollywood rumor has it that 20th Century Fox has signed director Sir Ridley Scott, who describes the subject as a passion of his, for a new movie on the battle. As many of the original’s warbirds are still flying, and so many more are being restored that there are more Spitfires and Hurricanes available now than in 1968, using real planes might be cheaper than CGI. And a whole new generation might hear those same Merlins roar again. ✯

—Frequent contributor Don Hollway wrote about making The Blue Max in our July 2015 issue. For further reading, he recommends: Battle of Britain: The Making of a Film, by Leonard Mosley, and Battle of Britain: The Movie, by Robert J. Rudhall.

You can convert your own HA-1112 M1L Buchón into a “Movie Messerschmitt,” just click here.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.