[dropcap]A[/dropcap]s 1944 dawned, the Arsenal of Democracy was in full swing. Production had soared in 1943, giving Allied troops a cornucopia of weapons, ships, planes, and tanks. The Allies had taken Sicily and landed in Italy, the long-awaited invasion of France was imminent, and American forces were steadily advancing toward Japan. Victory was in the air, but that scent brought its own dangers: complacency and overconfidence in industry and the workforce. These insidious foes, officials feared, threatened to prolong the war and put American lives at risk.

To counter this, Washington devised an unusual and ingenious plan to give a wakeup jolt to the defense industry with a headline-grabbing public relations blitz, culminating in the largest and most spectacular pep rallies the nation had ever seen. The goal, Life magazine said, was “to arouse and inspire the people of a critical industrial area to still greater effort in the momentous months of 1944.”

On the surface, wartime production was above reproach. Aircraft manufacturing had jumped from 19,433 planes in 1941, to 47,836 in 1942, and to 85,898 in 1943. Shipbuilding had leaped from 1,334 naval vessels in 1940-41, to 8,035 in 1942, and to 18,434 in 1943. Beneath the surface, however, things were not as rosy as they seemed, government officials insisted. Despite seemingly robust production levels, officials claimed the numbers could and should be higher.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt defined the problem in his 1944 State of the Union address. “Overconfidence and complacency are among our deadliest enemies….That attitude on the part of anyone—government or management or labor—can lengthen this war. It can kill American boys,” he said.

“Last spring—after notable victories at Stalingrad and in Tunisia and against the U-boats on the high seas—overconfidence became so pronounced that war production fell off,” Roosevelt explained. In June and July 1943 alone, he said, “more than 1,000 airplanes that could have been made and should have been made were not made. Those who failed to make them were not on strike. They were merely saying, ‘The war’s in the bag, so let’s relax.’”

Roosevelt echoed an alarm officials had been sounding since mid-1943, when Donald M. Nelson, chairman of the War Production Board, had warned of overconfidence in the workplace and urged defense workers “to put everything we have into another burst of productive energy.” In July 1943, Vice Admiral Frederick J. Horne, vice chief of naval operations, had thrown cold water on complacency when he predicted that the Pacific War could last until 1949 and called expectations of an imminent German collapse “wishful thinking.”

Since the beginning of the war, the government sponsored rallies at defense plants to spur workers on. In early 1943, Tom and Alleta Sullivan, whose five sons were lost at sea in the Pacific, toured shipyards and urged greater production so that “many more sons will come home to their mothers.” Returning war heroes spoke at other defense plants. Officials chose Los Angeles as the focal point of their special 1944 publicity blitz because the West Coast, especially California, was a booming epicenter of wartime production. West Coast aircraft plants built about 38 percent of the nation’s planes, and its shipyards accounted for about 44 percent of its merchant ships. Twenty-seven billion dollars flowed to the West Coast through production and building contracts, and many companies rode the wave, including a little outfit called Hewlett-Packard that went from nine employees and $37,000 in sales in 1940 to 100 employees and one million dollars in sales in 1943.

California’s workers had never had it so good. Unemployment fell from 15.2 percent in January 1940 to 0.3 percent in October 1943, and the Golden State topped the nation in per capita income. So many people came west for work that observers began calling the boom the “second Gold Rush.” John Steinbeck’s Okies had found the promised land.

If defense workers, especially in California, could only be spurred to greater effort, officials reasoned, industrial output would meet the government’s lofty goals and help bring the war to an expeditious end.

THE PUBLIC RELATIONS offensive began with a two-day meeting, January 8-9, 1944, between government officials and 650 West Coast industrial and labor leaders, public officials, and radio and newspaper executives in Los Angeles. Time magazine called the meeting a “facts-of-life” talk with “West Coast bigwigs.” The government’s message was clear: don’t let up because the war was a long way from being over.

The surprise guest at the conference was Admiral William F. Halsey, just back from the Pacific, who provided the hellfire and brimstone when he told the audience, “The only good Jap is one that’s been dead six months. The only thing to do is to kill all of them.”

Other speakers were more sedate in tone. They acknowledged progress in the war, but, the New York Times said, “expressions of confidence…were tempered with warnings about the tremendous obstacles to be faced.” There were “more jungles, many more islands” to be taken on the road to Tokyo, said Undersecretary of War Robert P. Patterson. The German army still had the will to fight and, in fact, had more than three times as many combat troops as when the war began, said Colonel Curtis H. Nance, an army intelligence officer.

As for industrial output, a peak in production had not been reached yet and was not even in sight, said Rear Admiral W. H. P. Blandy, former chief of the navy’s Bureau of Ordnance. Brigadier General Frank Armstrong Jr., who had led some of the earliest bombing raids in Europe, claimed the air force lacked the planes needed to bring Germany to its knees, and army Major General W. D. Styer beseeched union officials to impress on workers that “they aren’t making nuts and bolts, or lumber or sheet metal, but are passing the ammunition to the soldiers.”

The heart-to-heart talk was only a warmup for the extravagant centerpiece of the campaign. The site was the LA Coliseum, home of the 1932 summer Olympics and a venue that seated more than 100,000. That capacity was tested when nearly a quarter of a million people jammed the Coliseum on the evenings of January 8 and 9 for the show.

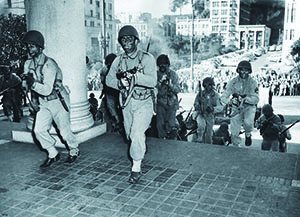

Craftsmen had converted the football field into a lifelike Pacific atoll, complete with palm trees and enemy fortifications. One hundred and fifty soldiers from the 140th Infantry Regiment stormed the field with machine guns, grenades, and field pieces in an attack that, Life magazine said, “rocked the stadium with thunders of combat and mottled the vast arena with flakes of fire.” As the troops pressed their attack, Life said, “geysers of earth rose into the air and smoke curled across the field in green, floodlit scarves.” A wind machine, donated by a nearby movie studio, enhanced the special effects. As spectators watched the attack, bright searchlights pierced the nighttime sky as wave after wave of U.S. Army Air Forces planes zoomed over the stadium. The victorious troops advanced, and an army chaplain delivered last rites to the fallen.

With ears ringing and heads spinning, the audience stood, reciting en masse a solemn pledge to “devote myself wholeheartedly to the war effort” and “to do all in my power to stay on the job and finish the job.” The show ended with a rousing version of “God Bless America.”

For the next week, the government saturated West Coast airwaves and newspapers with public service announcements imploring industry workers to “stay on the job and finish the job.” Time brought the message nationwide by featuring talks with business and labor leaders in its January 17 edition, and Life carried a photo spread of the Coliseum event in its January 24 issue. “Stay on the job and finish the job” became a rallying cry, appearing on lapel pins worn by war workers and on patriotic posters hung in defense plants.

The stay-the-course show went on the road to northern California later that year, playing to more than 350,000 war workers at Seals Stadium in San Francisco and at the University of California’s Memorial Stadium in Berkeley. “So impressive was the War Show,” said the Berkeley Daily Gazette, “that it is believed most of the 210,000 who witnessed it here have renewed their determination to ‘stay on the job and finish the job.’”

The Daily Gazette was right; defense workers got the message loud and clear. In 1944, American airplane production rose 12 percent, and naval shipbuilding jumped 58 percent. Combat boot production soared from 605,000 pairs to 12.6 million pairs, and the output of bazookas jumped from 98,284 to 215,177. Thanks to those workers who stayed on the job, America’s soldiers, sailors, and Marines had the tools needed to finish the job and come “home alive in ‘45.”✯