AS AN AMERICAN BOY growing up during the 1960s, I loved World War II movies, for all the obvious reasons: the action; the cool tanks, aircraft, and warships; the clear-cut contest between heroes and villains. Our family’s television offered a cornucopia of them, available almost constantly. But there was also film I watched, night after night, that bore scant resemblance to those World War II movies from which I derived my picture of warfare. It was the Vietnam War combat footage that dominated the evening news. The grunts in Vietnam neither looked, talked, nor acted like the soldiers I saw in movies, and the cause for which they fought often seemed dubious, even to them.

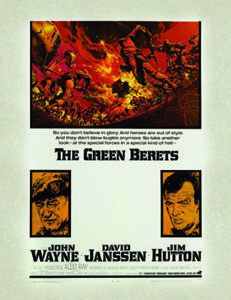

Worse, it became clear that a growing number of my countrymen were ambivalent about the war. I found this alarming; so did screen icon John Wayne. He decided to make a propaganda film that would inspire more support for it, focusing on the U.S. Army Special Forces—elite troops trained in unconventional warfare. Most Americans had heard of them, thanks to “The Ballad of the Green Berets,” Billboard’s number-one single for 1966, written and sung by Army Special Forces medic Barry Sadler.

Wayne commissioned a screenplay for the film, based loosely on Robin Moore’s novel The Green Berets. The script worked overtime to argue that the Vietnam War was the moral equivalent of World War II, the quintessential “good war” of heroes against bad guys. It did so not just rhetorically but by its choice of story. The first draft called for the Green Berets to infiltrate far above the demilitarized zone and kidnap a prominent North Vietnamese general—a plot familiar to any filmgoer who had seen a movie about a World War II commando raid. However, when Wayne took the script to the U.S. Department of Defense to secure its assistance in making the film, the department objected that the kidnapping did not correspond to the primary Green Beret mission—and anyway, the United States ground forces conducted missions exclusively within South Vietnam.

After listening to these and other concerns, Wayne produced a new screenplay that was now a shotgun marriage between the World War II commando raid genre and the western, another reliable vehicle for starkly portraying good guys and bad guys. The commando raid remained, but preceding it was a long segment about the defense of a remote fire base (nicknamed Dodge City) against an all-out North Vietnamese assault. The revised script passed muster, and thereafter The Green Berets received lavish production assistance from the U.S. Army, with dozens of Huey helicopters placed at the film crew’s disposal and a platoon of native Hawaiian soldiers given administrative leave to serve as Vietnamese extras. Standing in for Vietnam was Fort Benning, Georgia. Wayne both directed and starred in The Green Berets. Released in June 1968, it was the only major theatrical film about the Vietnam War to appear while the conflict was still underway.

The first scene sets forth the film’s ideology as starkly as possible. Colonel Kirby (John Wayne) looks on as two Green Berets sergeants brief an assembled group of liberal journalists. One of them, George Beckworth (David Janssen), tells the NCOs, “There are lots of people that believe this is a war between the Vietnamese people. Let’s let them handle it.” “Let them handle it?” echoes one sergeant, tossing a number of captured weapons onto the table in front of Beckworth and naming the Soviet-bloc country in which each was manufactured. “It doesn’t take a weight to fall on me or a hit from those weapons to recognize that what’s involved is Communist domination of the world.”

The Vietnam War is thus a struggle between freedom and slavery—the same trope as with the Axis, except that it is now applied to the Communists. It’s also made clear that the Nazis have nothing on the Viet Cong in terms of their willingness to commit atrocities. And, of course, The Green Berets draws strong parallels between the sneaky, treacherous Viet Cong and those sneaky, treacherous “Japs,” familiar from older World War II movies.

Critics excoriated The Green Berets when it appeared, partly for its politics but primarily because it was simply a dreadful film, made so in part by Wayne’s insistence on retaining the World War II commando raid sequence even though the preceding segment, which deals with the defense of the fire base, is so lengthy and dramatic that the raid itself becomes anticlimactic. But it is telling that Wayne refused to discard it. He understood all too well the iconic power of World War II as “the good war.” And The Green Berets succeeded in transforming Vietnam into something an eight-year-old American boy could understand. I loved it.