One of the classic war films in American cinematic history almost never have made it to the silver screen.

THROUGHOUT ITS HISTORY, Hollywood has had a symbiotic relationship with the U.S. Armed Forces. The film industry has drawn heavily from the military for authenticity, particularly the use of ships, aircraft, and other equipment—and often of actual service personnel as movie extras. The military, in turn, has benefited from Hollywood as a major public relations vehicle to place it in a positive light. Some film projects have been so promilitary that support from the armed forces has been unstinting. Others have been so fundamentally antiwar that support has been out of the question. Still other movies have been problematic—one major example being 1954’s The Caine Mutiny, based upon Herman Wouk’s 1951 bestselling novel.

The film tells the story of a World War II destroyer–minesweeper and its crew, who gradually become convinced that the ship’s captain, Lieutenant Commander Philip Queeg, is dangerously unstable. His executive officer, Lieutenant Steve Maryk, decides to relieve Queeg—a decision backed by the other officers—when the captain appears to become unglued during a typhoon. Maryk is subsequently court-martialed and charged with “conduct to the prejudice of good order and discipline,” but he is acquitted after his defense attorney, Lieutenant Barney Greenwald, exposes Queeg’s mental instability when the captain takes the witness stand.

According to Lawrence H. Suid’s Guts and Glory: The Making of the American Military Image in Film (2002), when film producer Stanley Kramer sought the navy’s assistance in bringing the novel to life, the navy had any number of concerns, starting with the film’s title: couldn’t it be The Caine Incident instead? The navy was also suspicious of Kramer, who had a reputation as a maverick. Kramer could have dodged the need for the navy’s help by focusing on the court-martial itself—Wouk had already written and produced a play, The Caine Mutiny Court-Martial—or by utilizing ship models. But Kramer insisted that the production required the scale and realism that only actual warships could provide. When Wouk appeared to back away from the project after the navy balked, Kramer accused the writer of being “some sort of jellyfish.”

The film might never have been made but for the intervention of Admiral William M. Fechteler, the navy chief of operations, who overrode the objections of his subordinates—including the admiral who served as chief of information—and ordered full cooperation for the project. Ultimately this included, among other things, the loan of an aircraft carrier and two destroyer-minesweepers to represent the Caine. Why did Fechteler do this?

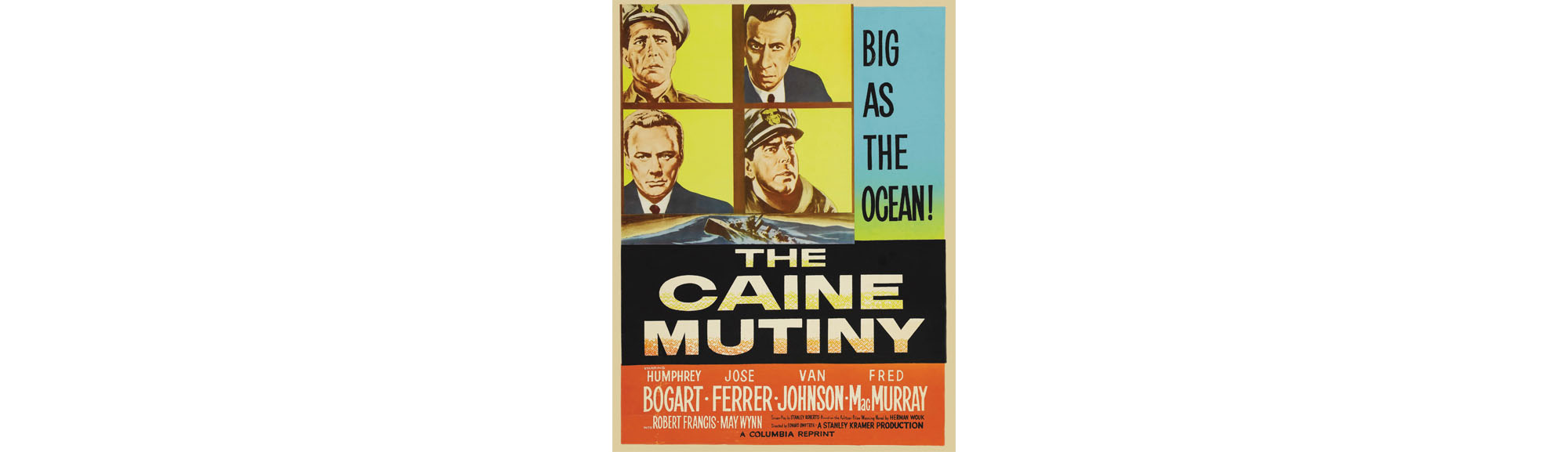

To start, Fechteler seemed not at all concerned that the film might cast the navy in a negative light. He wondered only how Wouk, a naval reservist who had served during the war aboard two minesweepers, could have encountered “all the screwballs I have known in my thirty years in the navy.” But Fechteler also intuited that the navy’s support would influence the filmmakers to portray the service positively. Ultimately the movie, released in June 1954 with Humphrey Bogart in the role of Queeg—one of Bogart’s most memorable performances—underscored the fact that the Caine was atypical of the rest of the fleet.

The film also made Queeg a more sympathetic figure, and the navy’s decision to place him in command more understandable. In the novel, Queeg is dangerously insane. In the film, he is shown as a dedicated officer who is simply worn out by years of strenuous duty and robbed of needed support by his subordinates. Despite having saved Maryk’s hide, defense attorney Greenwald has nothing but contempt for the officers of the Caine. “You didn’t approve of his conduct as an officer. He wasn’t worthy of your loyalty, so you turned on him…. If you had given him the loyalty he needed, do you think the whole issue would have come up in the typhoon?”

That is one way that Kramer vindicated Fechteler’s decision. Kramer also argued, correctly, that film audiences would understand that the navy was basically competent—how else could it have won World War II?—and that the Caine was therefore an aberration. And, inevitably, he dedicated the film to the U.S. Navy and included the disclaimer that there had never been a mutiny aboard a navy vessel (although a well-known mutiny had occurred in 1842 aboard the USS Somers). It remains the case, however, that without Fechteler’s intervention, one of the classic films in American cinematic history would never have made it to the silver screen. ✯