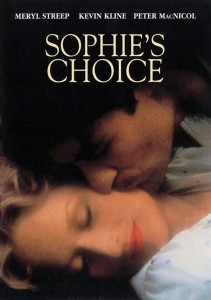

The phrase “Sophie’s Choice” has entered the vernacular to mean an impossible dilemma, a choice that is morally unbearable. It comes from the title of William Styron’s acclaimed 1979 novel which was later adapted into a 1982 film starring Meryl Streep as Sophie, in a powerful performance that won her an Academy Award for Best Actress.

The phrase “Sophie’s Choice” has entered the vernacular to mean an impossible dilemma, a choice that is morally unbearable. It comes from the title of William Styron’s acclaimed 1979 novel which was later adapted into a 1982 film starring Meryl Streep as Sophie, in a powerful performance that won her an Academy Award for Best Actress.

By now, everyone knows that Sophie was a Polish Holocaust survivor forced to choose which of her two young children would live and which would die. She gradually reveals that truth, like the peeling of an onion, to an aspiring writer named “Stingo” (Peter MacNicol), who befriended Sophie and her lover Nathan (Kevin Kline) two years after the war at the Brooklyn boarding house where the three live, and who also narrates the film from a vantage point many years later. That truth haunts the movie—director Alan J. Pakula described the film as a ghost story—but so does the man who made her choose, a nameless SS camp doctor (Karlheinz Hackl).

The film contains two flashbacks. The SS doctor appears in both. The first and longest unfolds over 32 minutes as Sophie, a Catholic, explains that she was arrested for stealing a contraband ham and sent to Auschwitz with her two children. Her seven-year-old daughter, Eva, was taken directly to the gas chambers while her nine-year-old son, Jan, went to the Kinderlager, the children’s camp. Because she spoke fluent German, Sophie found herself working in the residence of Auschwitz commandant Rudolf Höss (Günther Maria Halmer).

The second flashback runs just under six minutes and depicts Sophie and her children’s initial arrival at Auschwitz, including the moment when the terrible choice is forced upon her.

Let’s take these in chronological order, not the order in which they appear in the film. Upon arrival at Auschwitz, Sophie and her children join a long line of others as they wait for whatever the Nazis have in store for them. The SS doctor—who holds the rank of Hauptmann, or captain—walks slowly and dispassionately along the line of arrivals. He has not yet made any decisions about which people will go to the labor camps and which will be immediately gassed. Sophie’s striking beauty makes him halt.

“You’re so beautiful,” he whispers to her. “I’d like to get you in bed.”

He asks if she is a “Polack” or one of “those filthy Communists.” She says nothing. He starts to walk away. She decides to call after him.

“I am not a Jew! Neither are my children! They’re not Jews. They are racially pure. I’m a Christian. I’m a devout Catholic.”

That gets the doctor’s attention. He turns slowly and walks back to her. “You’re a believer?

“Yes, mein Hauptmann. I believe in Christ.”

“So you believe in Christ, the Redeemer?”

“Yes.”

The doctor looks at Jan, then Eva, whom Sophie is carrying in her arms.

“Did He not say, ‘Suffer the little children to come unto Me’?” A short pause. Then: “You may keep one of your children.”

She cannot comprehend this at first. He explains that one of her children can stay but the other must go, and she has the “privilege” of making the choice. She screams repeatedly that she cannot choose, but finally he snaps, saying that if she does not choose, he will take them both. Only when a guard reaches out to seize Jan and Eva does Sophie say, “Take my baby! Take my little girl!” The camera follows Eva, who screams hysterically as the guard carries her away like a sack of potatoes.

The first on-screen flashback, which chronologically takes place weeks later, follows Sophie’s experience in camp commandant Höss’s household. It includes a scene in which Höss has lunch on his patio with the SS doctor. In the flashback’s context in the film, the audience does not yet know who the doctor is, and Sophie barely appears in the scene (she is the servant). Her back is turned to the camera as she brings Höss a bottle of wine. In that sense, the scene is a slight cheat: Sophie could not know the content of the conversation and therefore could not later recount it to Stingo, and she would surely have recognized the SS doctor. But it is an indispensable window into the darkness at the center of Sophie’s Choice.

“You are looking well,” Höss says to the SS doctor, who has just returned from leave.

“Ja,” responds the doctor. He is pensive. “I hardly drank after I left here,” he says quietly, implying that he has been relying on alcohol to endure his duties at Auschwitz. “Can you imagine? My father asked me what kind of medicine I practice here. What can I tell him? I perform God’s work. I select who shall live and who shall die.” He pauses, then asks: “Is that not God’s work?”

In this scene, Pakula, who wrote the screenplay in addition to directing the film, is trying to convey William Styron’s speculation in the novel about the SS doctor who offers Sophie the “choice” and what motivates him. Looking back, the mature Stingo believes that the doctor must have been “unique among his fellow automata: If he was not a good or a bad man, he still retained a potential capacity for good and his strivings were essentially religious.” But the state-sanctioned, industrialized slaughter at Auschwitz seemed to be beyond good and evil. It removed sin, and in the doctor’s mind it therefore removed God.

“Was it not supremely simple, then,” Stingo writes, “to restore his belief in God and at the same time affirm his human capacity for evil by committing the most intolerable sin that he was able to conceive?” ✯

Originally published in the July/August 2016 issue of World War II magazine. Subscribe here