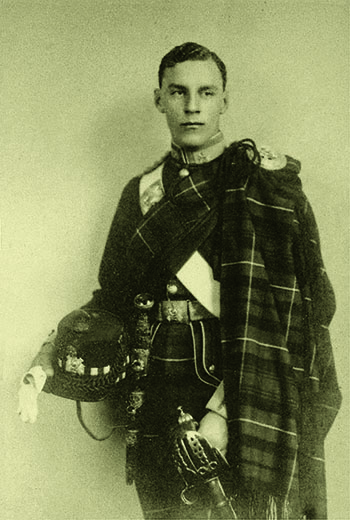

[dropcap]F[/dropcap]or more than a year, Major Geoffrey Keyes had craved action. He wanted to prove himself—as a soldier and as a son worthy of his illustrious father, Roger Keyes, a First World War hero and one of the greatest sailors of his generation.

Young Geoffrey was slight of build, sensitive, and unsuited to war in many respects. Still, in June 1940, he had volunteered for combat and now, 12 months on, he was about to get a taste of it. But as he and his 140-strong landing party waded through the surf onto the sand along the western coast of Syria, there was a problem: they were at the wrong beach. They should have come ashore north of the Litani River—from where they would assault barracks held by Vichy French forces—but they had landed to the south.

Keyes took the error in stride. He informed his men and ordered them to drop their heavy haversacks. He would lead them north, ford the Litani, and attack as planned.

The commandos struck out toward the river, passing through a company of Australian infantrymen who had come ashore nearby. The Australians had seven collapsible canvas boats, but warned Keyes that enemy forces on the other side of the river had repeatedly prevented them from crossing. Keyes took the boats and pushed on toward the 40-yard ribbon of water. Suddenly, a flare burst in the dark sky. Then all hell broke loose.

THE JOURNEY THAT LED the commandos to a Syrian beach began one year earlier, when British prime minister Winston Churchill instructed his chiefs of staff to raise a special service unit of irregular troops to strike at the Germans. By fall 1940, more than 2,000 men had volunteered and were organized into a dozen commando units. Keyes was posted to No. 11 (Scottish) Commando.

Commanding officer Colonel Dick Pedder quickly molded the volunteers in Keyes’s unit into a well-drilled troop that considered itself a match for any enemy force. At the end of January 1941, the unit sailed for the Middle East, where Vichy French forces—allied with their German conquerers—had allowed the Luftwaffe the use of Vichy airfields in Syria to launch attacks on the British. But for several months, the men of No.11 Commando endured a frustrating series of aborted raids and cancelled operations.

When they received a rush order on June 3 to embark from their Cyprus base, the commandos were skeptical they would see action. In fact, their first real test lay ahead—an opportunity to demonstrate that a battalion-size force of elite troops could fulfill Churchill’s demand for “a vigorous, enterprising and ceaseless offensive” against the enemy.

The commandos first sailed to Egypt’s Port Said, where Colonel Pedder set off for Jerusalem to confer with General Sir Henry Maitland Wilson, commanding officer of British forces in Palestine and Trans-Jordan (then a British Protectorate, now Jordan). To square off against a Vichy army of 35,000 men, General Wilson had at his disposal the 7th Australian Infantry Division, part of the 1st Cavalry Division, a brigade of Indian soldiers, a small number of Free French soldiers, and No. 11 Commando.

Pedder’s men were to land on Syria’s western coast near the Litani River—“a green fast stream bearing rich banana groves on its banks,” in the words of Australian war correspondent Alan Moorehead. The commandos would eliminate enemy resistance and seize a bridge to enable the 21st Australian Infantry Brigade to advance toward Beirut. The river, however, was much more than a stream—up to 40 yards wide near its mouth—and Wilson cautioned that the bridge had probably been demolished. Scarce intelligence suggested that two Vichy battalions were holding fortified positions facing south.

Pedder split his force into three small troops for the operation. Geoffrey Keyes would lead X Troop, which would land just north of Litani River and conduct the main push to Qasmiye Bridge. Pedder would command Y Troop and provide support, while the smaller Z Troop would land two miles north of the river, near the Kafr Badda Bridge, to block enemy reinforcements.

For the eager commandos, it was new territory—and disarmingly picturesque. As BBC correspondent Richard Dimbleby wrote, “the coastal front in Syria was attractive to look at. There was the warm Mediterranean, incredibly blue, breaking gently on the rocks and inviting you to leap in and swim. There were little beaches and fresh green ground lying behind them, and in the background there were the hills flanking the coastal plain…. It was good to look at. It was hell to fight in.”

ON THE WARM AND STILL MORNING of June 9, the commandos’ troopship arrived off the Syrian coast. At 3 a.m., their 11 assault craft approached the beaches—and the plan quickly went haywire. Pedder’s Y Troop was the first to come ashore, and it immediately came under heavy machine-gun, rifle, and mortar fire from 300 yards to the south. “We crawled off the beach and advanced along a dried river bed,” recalled Regimental Sergeant Major Lewis Tevendale. Nearby, Lieutenant Gerald Bryan, a laconic 20-year-old Ulsterman who had volunteered for the commandos from the Royal Engineers, tried to untie the lifebelt attached to his rifle as he advanced along a ditch. The ditch soon narrowed and he had to climb out into the open. “The ground was flat with no cover,” Bryan remembered. “The machine guns were now firing fairly continuously.”

As Y Troop continued to move inland, Bryan paused to survey a map with one of his corporals. Suddenly, there was a crack. The corporal fell forward, shot through the eye by a sniper. Vichy French soldiers opened fire from only 20 yards away. After scrambling for cover, the commandos shouted to one another that an enemy 75mm gun emplacement was up ahead; its crew was firing at them from slit trenches. Bryan barked orders and led his commandos in a low crawl toward the enemy position. When they were within range, they hurled grenades and charged, killing the French soldiers. “It was rather bloody,” Bryan remembered dryly.

One of his men, Sergeant Tommy Worrall, was an artilleryman by training and quickly familiarized himself with the French artillery gun. “We seized one of their 75s in the battery,” he recalled, “and with it blew two of the three remaining cannon from the face of creation at a distance of 20 yards.” Worrall then disabled the firing pin of the gun with a rifle butt and dashed across open ground to join the others at Colonel Pedder’s position.

Pedder explained that Keyes’s X Troop had come ashore several miles south of their intended location and was behind schedule. So he ordered Bryan to provide fire support while he led Y Troop’s headquarters section toward the enemy barracks and high ground east of a banana plantation known as Aiteniye Farm that comprised several rudimentary buildings encircled by barbed wire entanglements.

“We took up what positions we could but there wasn’t much cover,” Bryan said. French forces quickly spotted his men and engaged them with heavy small-arms fire. “The whole time bullets spat past my head and sounded very close,” he recalled. Bryan’s luck held, but a sniper shot a fellow officer, Lieutenant Alistair Coode, in the chest. Coode went down, coughing blood.

Further inland, Pedder led his men forward, Sergeant Major Tevendale at his side. They moved along a deep gully north of the barracks. There, Tevendale recalled, they captured “several prisoners, who were guarding large quantities of explosives and ammunition stored in two separate quarries.”

Pedder left a detachment of men to guard the prisoners and headed northeast, only to come under fire from machine guns and snipers concealed in the trees to their front. “It was hell,” a commando recalled. “French machine guns and snipers were there by the score. Deliberately, they permitted us to advance, and then when we went down on our knees or otherwise sought cover from their machine guns, the snipers perched in trees behind us had a go.” Pedder decided to withdraw south to try and link up with X Troop, but enemy fire intensified.

It was then, Tevendale recalled, that a bullet grazed Pedder’s helmet; “he turned around to joke with us, regarding his good luck,” when more bullets struck Pedder in the head and back. He died instantly.

Relentless enemy fire forced Bryan’s men to fall back. He ordered them to sprint to scrub about a hundred yards distant. “All the time bullets were fizzing past much too close for comfort and we kept very low,” Bryan recalled. “Sergeant Worrall, who had already been wounded, decided to run for it, to catch us up, but a machine gun got him and he fell with his face covered with blood.”

Then Bryan felt a jackhammer pain in his legs. He dragged himself into a hollow and surveyed the damage. “There was a gaping wound in my right leg just above the foot,” he remembered. He fumbled in his pocket for a morphine pill, swallowed it, and tried to stop the bleeding. The section stayed pinned down for the next two hours, after which enemy fire suddenly increased and 25 Vichy soldiers advanced out of the scrub, bristling with bayonets. They captured Bryan and his men.

With all the headquarters section’s officers struck down, Tevendale led the men to high ground. They took positions along the road connecting the Vichy barracks to the river, firing on enemy forces who were pulling back from heavy Australian shelling. But, Y troop could not keep the enemy at bay; by late afternoon, Vichy forces had captured Tevendale and his men.

FURTHER NORTH, Captain George More led Z Troop ashore like a malevolent breeze off the sea, moving inland over the main coastal road toward the high ground east of the Kafr Badda Bridge. They encountered four trucks of Vichy French soldiers, some trying to unload two Hotchkiss heavy machine guns. The commandos killed the enemy soldiers and destroyed the trucks.

Then Lieutenant Tommy Macpherson, a 20-year-old Scot and an accomplished sportsman, led his section toward the bridge, about three-quarters of a mile away. Given the flat, open terrain, the commandos had no choice but to make a frontal assault.

The Lebanese-French troops they faced were well dug-in and had at least two machine guns and mortars, but were, Macpherson recalled, “of somewhat unenthusiastic quality.” When the enemy saw the commandos charge and heard their Gaelic yells, they abandoned their positions on an otherwise fiercely fought morning, leaving behind their wounded and heavy weapons.

After losing Kafr Badda Bridge, Vichy forces counterattacked at noon with eight light armored vehicles. After neither side gained an advantage, six more Vichy armored cars arrived by 4 p.m. At the prospect of facing 10 armored vehicles, the commandos on the bridge fell back toward the beach. There, they linked up with the rest of Z Troop and Captain More, who ordered them to withdraw south and cross the Litani. He split Z Troop into two parties: one set off for high ground to the east and successfully crossed the river; the other descended toward the beach, where enemy forces quickly pinned them down with heavy machine-gun fire. Unable to move, the commando party was forced to surrender.

To the south, Geoffrey Keyes and X Troop were still sheltered in hastily dug slit trenches, as enemy fire—75mm guns, 81mm mortars, and heavy machine guns—swept the 200 yards of open ground that lay between them and the southern bank of the Litani River. Keyes surveyed the ground and radioed for artillery support to suppress the Vichy forces. As the Australians dropped a heavy barrage on the Litani’s opposite bank, Keyes sent seven commandos across the river in a collapsible boat. They slithered into thick scrub and began throwing grenades toward the enemy positions. By midday, Keyes sent seven more men across, and the 14 commandos on the north bank convinced 35 Vichy soldiers to surrender. They secured a 25mm antitank gun and several heavy machine guns. They also had the presence of mind to grab some rations of French bread.

After Keyes forded the river, the commandos ate their first meal of the day and discussed what to do about the last Vichy artillery piece in the area—a 75mm gun that, although 1,000 yards away, continued to shell the Litani’s south bank. The gun was well hidden and Australian artillery had been unable to knock it out. With information from their new prisoners, the commandos turned the newly captured 25mm antitank gun around so it was pointed north. They fired three shells to range the enemy’s 75mm gun and, with a fourth shot, destroyed it.

By evening, X Troop took up defensive positions in a well-fortified machine gun emplacement while the Australian brigade pushed on toward Aiteniye Farm. Unknown to Keyes and the Australians, Aiteniye contained 24 recently captured commandos from George More’s Z troop. The Australians attacked at around 9 p.m. and, after an hour-long engagement, drove off the Vichy forces and freed the commandos.

Unaware of the Australians’ success, Keyes rose early the next morning, determined to lead a crushing assault on Aiteniye. But as he surveyed the objective, he was stunned to see Captain More walking toward him—with a senior French officer holding a white flag. The Vichy French had decided to surrender rather than risk annihilation.

As the Australians accepted the French surrender, the three troops of No. 11 Commando linked up and could finally rest. Keyes received an “awful shock” to learn that Colonel Pedder was one of five commando officers killed, with 123 casualties. But Keyes also learned of his commandos’ courage and acts of bravery during their baptism of fire: a medic had crawled through enemy fire to aid a wounded comrade before being killed himself, two sergeants repeatedly went into enemy-held woods to hunt for snipers, and a Y Troop officer captured 80 Frenchmen.

By midday, the 21st Australian Brigade crossed the Litani River to begin advancing toward Damascus, where the Vichy French, with Luftwaffe support, continued to put up stiff resistance. The Syrian capital fell on June 21, and the Allies continued north to Lebanon. On July 10, Vichy commander General Henri Dentz asked for an armistice; it went into effect four days later.

ALTHOUGH NO. 11 COMMANDO achieved its objectives during the battle, the operation had been rife with setbacks. British leaders reassessing how best to utilize their units of special troops soon decided to disband the commando units in the Middle East; they found too few well-trained troops willing to fill their depleted ranks. The aggressive, thrill-seeking personalities sought action elsewhere. Some returned to their parent units, others volunteered for the Long Range Desert Group, and several dozen volunteered for a new unit that came to be known as the Special Air Service (SAS).

In November 1941, former commando David Stirling parachuted into Libya with 55 SAS men—many originally from No. 11 Commando. Stirling sought to prove that small teams of elite soldiers, using the advantage of surprise, could exact greater damage on the enemy than an entire battalion. Over the next 18 months, they raided Axis airfields in the desert, destroying at least 325 enemy aircraft and killing hundreds of enemy soldiers.

On the same day that Stirling launched his operation, Geoffrey Keyes led an audacious mission to assassinate German general Erwin Rommel at his headquarters in Libya. But their intelligence was faulty, and Keyes perished during the failed raid.✯