On the afternoon of April 18, 1861, Baltimore Mayor George W. Brown dispatched a strong letter of warning to Abraham Lincoln. “The people are exasperated to the highest degree by the passage of troops,” Brown wrote, “and the citizens are universally decided in the opinion that no more should be ordered to come. The authorities…did their best to day [sic] to protect both strangers and citizens and to prevent a collision, but [in] vain….it is my solemn duty to inform you that it is not possible for more soldiers to pass through Baltimore unless they fight their way at every step.”

Earlier that day five companies of Pennsylvania militia and a detachment of 4th Artillery Regulars ran into a rock-throwing mob at the Bolton Street station. Nicholas Biddle, a 65-year-old black orderly, caught the brunt of the crowd’s wrath. That incident, though minor, reflected the sectional tensions which destined America for civil war.

It was another thread in the seemingly endless tangle of problems facing the embattled U.S. president. Since December 1860, death threats had been pouring into Lincoln’s office. More than half a dozen states had already left the Union, and more were sure to follow. In the week leading up to the Baltimore confrontation, matters worsened. Confederate batteries fired on the besieged Federal garrison at Fort Sumter, and Virginia passed an ordinance of secession, leaving only a strip of river between the unguarded Union capital and enemy territory.

On top of this the president had to contend with Baltimore, a city the British once branded “a nest of pirates.” Its deeply pro-Southern populace made it unfriendly ground for the Rail Splitter, who had won a paltry 4 percent of its total popular vote in the last election. And now he’d received a letter in which Baltimore’s mayor expressed his citizens’ “universally decided” wish that he withdraw his order for 75,000 troops.

The suggestion was completely out of the question. The Confederate Army was preparing for battle just across the Potomac. Without a substantial military force to protect it, the U.S. capital remained an inviting target, and Northern troops’ shortest route was through the major railroad hub of Baltimore, the North’s gateway to the South. Lincoln knew that if Union forces were denied this vital transportation route, the North would lose the war before it started. He would have his soldiers, and he would have to get them by way of Baltimore—even if they had to fight their way through as Brown had warned.

The next morning a wood-burning locomotive chuffed south along the Philadelphia, Wilmington & Baltimore Railroad carrying 700 members of the 6th Massachusetts Volunteer Militia, the first outfit drilled and equipped to answer the president’s call for troops. Like the Minutemen of 1775, the 6th’s ranks had reported for duty without question or delay. On April 16, Major Benjamin Watson closed his law office in Lawrence with scarcely two hours’ notice. In Lowell 17-year-old Private Luther Ladd traded his machinist’s apron for a uniform and buff trimmings. Addison Whitney left his job in the Middlesex Corporation’s No. 3 spinning room. When members of this 11-company regiment—once farmers, merchants, tradesmen and lawyers—left for Washington, they were heralded by Northerners as the Union’s heroic protectors.

But the journey’s romance soured for the new troops as their train neared Baltimore. The regiment’s commander, Colonel Edward F. Jones, held dispatches from railroad officials warning that his men would likely meet strong resistance there. It was a stark contrast to the trip’s first 300 miles, throughout which jubilant crowds hailed them with refreshments and patriotic demonstrations at every station.

They would find no such hospitality below the Mason-Dixon Line, where a warlike mood prevailed. Quartermaster James Munroe issued each man aboard the train 20 rounds of ball cartridges in preparation for their arrival at the Baltimore station. According to Private William Gurley of Company K, all accepted their lot “solemnly [and] with unchanged features,” then capped and loaded their .58-caliber Springfields as ordered.

Few of the men spoke as they neared the city. The metallic scraping of ramrods and the train’s rhythmic clatter were the only sounds that filled the coach—that is, until Colonel Jones entered the car and broke the silence with an ominous set of instructions. “The regiment will march through Baltimore in column of sections, arms at will,” he announced. “You will undoubtedly be insulted, abused, and, perhaps, assaulted, to which you must pay no attention…even if they throw stones, bricks, or other missiles….[B]ut,” Jones added, “if you are fired upon and any one of you is hit, your officers will order you to fire. Do not fire into any promiscuous crowds, but select any man whom you may see aiming at you, and be sure you drop him.”

With that, Jones moved on to the next car, leaving Gurley and his comrades to contemplate their fate. Ghastly images of mob violence flashed in their minds as they approached the northeast waterfront and Fort McHenry’s ramparts came into view, with a Union flag still flapping in the breeze.

Around noon the 6th pulled into the PW&B’s President Street depot, where things seemed eerily quiet. Their arrival went largely unnoticed by pedestrians, most of whom hadn’t yet realized that the train was carrying Federal troops. The calm wouldn’t last.

Rumors of the Federals’ arrival had already begun circulating, and Baltimore’s residents and local leaders made no secret of their disdain for the Union’s new administration. Some Baltimoreans’ distaste for the new president had no doubt been heightened by a recent incident involving Lincoln himself. Just two months before, the president-elect opted to sneak through Baltimore under cover of darkness, to avoid a possible assassination plot. Southern cartoonist Adalbert Volck lampooned that humiliating maneuver in an etching, Passage Through Baltimore, depicting a cowardly-looking Lincoln peeking through the side door of a boxcar.

Like all Washington-bound passengers arriving from Philadelphia, Lincoln had to switch trains at the B&O line’s Camden Station, a mile and a half west of the PW&B’s depot. Because a city law prohibited the passage of locomotives along busy thoroughfares, however, drivers had to use horses in teams of four to pull each car across town, where railroad workers then recoupled them to a B&O engine. The tedious transfer took passengers around the city’s harbor, four blocks north on President Street, a mile west on Pratt and two blocks south on Howard. Lincoln had traveled the route while the city slept in February, but on April 19 the 6th Massachusetts was about to make that trip in broad daylight, through streets teeming with Southern sympathizers. This short distance between stations would test the newly minted Union troops’ mettle as soldiers.

Baltimore had always been seen as an explosive city, hypersensitive to the shifting currents of politics. The present crisis was no exception. While most Baltimoreans felt that Lincoln should keep his hands off the South, there was also a smaller contingent of Confederate zealots there who were more than willing to go to war over it. Sending Northern troops through their hometown was like putting a lit match to a powder keg.

Railroad officials, keenly aware of the danger, wanted nothing more than to get the Massachusetts men out of town as quickly as possible. Before Colonel Jones could even begin organizing his planned march, workers had uncoupled the engine and hitched teams of bay mares to each car. In swift succession they rolled out of the yard and onto President Street. What happened next would catapult the 6th Massachusetts to near-mythic status—and also doom Baltimore to a lengthy military occupation.

Inside the rail cars, the air was thick with tension. Every man tightened his grip on his Springfield, and most avoided looking out the windows, for fear of locking eyes with a pro-Confederate rough. Meanwhile bystanders couldn’t help but notice the soldiers; their military caps and upright muskets betrayed the railcar passengers’ identities. By the time they had gone just a few blocks, the 6th had attracted an angry crowd, spewing a torrent of epithets punctuated by cheers for “Jeff Davis!”

The growing mob followed the line of cars, now seven long, as it turned onto Pratt Street, the east–west axis of the waterfront. By this time its ranks had swelled to several hundred. Suddenly the onlookers unleashed a shower of paving stones and gunfire on the seventh coach, which was carrying Major Watson and 50 troops. Two men were hit in the head and upper body with bricks, while another soldier lost his thumb to a pistol shot. Holding up his bloody hand, the latter requested permission to return fire, which Major Watson promptly granted. That volley repelled the rioters long enough for the major and his men to escape. Their car was the last to make it to Camden Station, arriving windowless and riddled with bullet holes.

Back at Pratt Street, an orgy of destruction unfolded. Rioters dumped heavy anchors and cartloads of sand onto the tracks. Charles Pendergast, a shipping agent who profited handsomely from transport between Baltimore and South Carolina’s Charleston Harbor, handed dockworkers crowbars and pickaxes with orders to pry the rails from the cobblestones and put the road out of commission.

Merchant Richard Fisher, in the middle of a business transaction with a Spanish sea captain, watched the rioters in horror from the second floor of his counting house. “You seem much agitated,” remarked the mariner. “This is nothing. We frequently have these things in Spain.” Fisher replied, “In Spain this may mean nothing; in America, it means Civil War.”

To the four companies stranded at the PW&B’s depot, it meant marching through a gauntlet of narrow streets flanked by tightly packed rows of brick buildings—terrain that put the 6th at a marked disadvantage. Military training of the day involved Napoleonic tactics for open battlefield scenarios, not a crowded, urban landscape such as Baltimore’s. What’s more, the Union men faced a plain-clothed enemy familiar with every inch of the neighborhood.

Once word came that the tracks were now impassable, the 220 men who still needed to reach Camden Station wheeled into columns outside the President Street depot under the command of stout Captain Albert S. Follansbee. Without hesitation, he gave the order to march. But as the columns moved forward, they were surrounded by a howling mob of secessionists shouting that they would kill every “white n——” of them before they reached Camden Station.

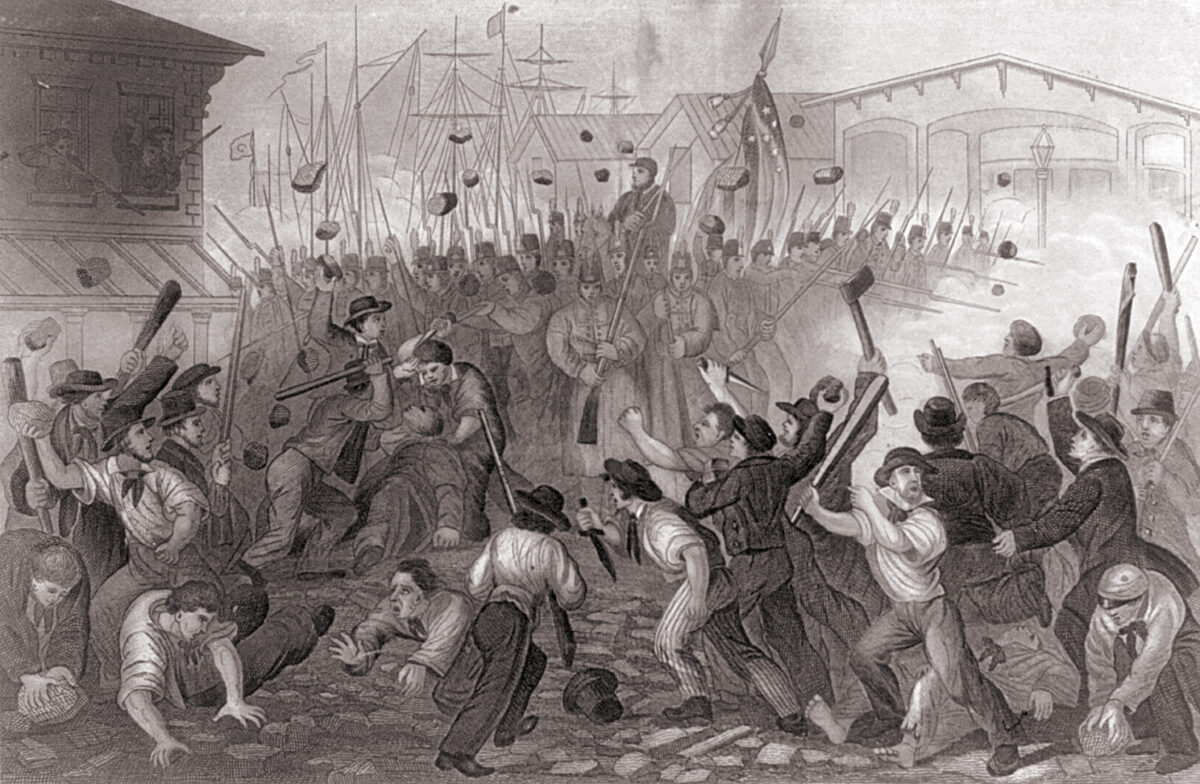

The soldiers pressed on while onlookers pelted them with anything they could throw. The rioters had littered their path with makeshift barricades, to slow the troops’ progress. One rioter drew a swell of cheers from the mob as he took up position at the front of the 6th’s line, marching oafishly while dangling a Southern Palmetto flag from a piece of flimsy lumber. Three blocks of this charade was all that Lieutenant Leander Lynde could take. He coolly stepped out of line, ripped down the flag and shoved it under his coat, then rejoined the march as though nothing had happened. The crowd responded with a fusillade of bricks and gunfire that injured at least six troops.

Meanwhile Mayor Brown rushed east on Pratt Street to find the bridge near President Street covered with anchors and scantling. He curtly ordered nearby police officers to clear the obstructions, then hurried off to meet the advancing Massachusetts soldiers. They rounded the bend from President Street at the double quick, firing haphazardly at the mob, which was close on their heels. Just moments earlier some of Follansbee’s men had been attacked. A few were shot or beaten senseless.

The mayor and Follansbee met at the base of Pratt Street, and Brown introduced himself. “We have been attacked without provocation,” gasped the winded captain. Brown nodded, adding the laughably obvious recommendation, “You must defend yourselves.” Follansbee pushed on without a word. No one was safe. Bullets whistled past from all directions, striking rioters, soldiers and bystanders.

Four blocks west, at the corner of Gay and Pratt streets, the mob let loose a heavy barrage of stones and hot lead. “[That’s] right! Give it to them!” a rioter shouted. “They won’t shoot, they’re too afraid of their cowardly necks!” shrieked another.

Finally Follansee barked out the order to fire. The 6th’s men raised their rifles and delivered a volley, then jogged 200 feet to South Street, where more stones and pistol shots rained down. Again the 6th returned fire. Eleven rioters dropped in that salvo, one of them hit in the throat.

That kept the mob at bay temporarily. But two blocks farther on, near the corner of Light Street, rioters hit the 6th’s men again, this time killing teenager Luther Ladd, who just two days before had traded his machinist’s apron for regimental dress. As the soldiers brought their guns to shoulder, Mayor Brown ran forward, shouting at them, “For God’s sake, don’t shoot!” Given the noise and chaos at that moment, it’s unlikely that anyone heard him.

The regiment fired into the crowd one last time before Police Marshal George Proctor Kane and 50 officers arrived to form a barrier between the troops and the mob. To ensure that no one attempted to pass, Kane, a burly, no-nonsense tough, raised his revolver and cried out, “Keep back, men, or I shoot!” Kane’s reputation intimidated even the roughest thugs, helping to quell the riot. Moments later the 6th was able to march the rest of the way to Camden Station, where they boarded a train to Washington, D.C.

Though the fighting had lasted less than an hour, there was a sizable butcher’s bill. From the 6th Massachusetts, Addison Whitney, Luther Ladd, Sumner Needham and Charles Taylor were killed during the march. What’s more, Taylor’s face had been smashed beyond recognition from repeated blows with heavy paving stones. Thirty-six others in the regiment were wounded, many of them seriously. Of the rioters, 11 died—among them a ship’s cabin boy who was hit in the stomach by a stray bullet. Countless others stumbled away to nurse their wounds.

Reaction to the riot extended well beyond Baltimore. Many Americans, North and South, had still held out some hope that the conflict might be resolved before much blood was shed. North Carolina Congressman A.W. Venable, for example, had optimistically proclaimed that he would be able to wipe away every drop of blood shed in the war with a handkerchief.

The events of April 19 extinguished that last spark of hope. It was now clear that a long and bloody conflict lay ahead. The men of the 6th Massachusetts Regiment came to Baltimore with romantic notions of war. They left knowing how bitter it would be.

Journalist Michael Williams’ forthcoming book City Under the Guns tells the story of the military occupation of Baltimore.