At 1:36 on the morning of May 4, 1942, air-raid sirens began to wail ominously over the historic city of Exeter in southwest England. Awakened by the ululating alarm, thousands of anxious citizens, many still in their pajamas, stumbled through the darkness to the comparative safety of their backyard air-raid shelters. Although Exeter had so far been spared the carnage suffered by other British cities in the war, a couple of isolated raids the previous week had set a worrying new precedent. The worst was still to come.

The Luftwaffe began to drop the first in a barrage of 10,000 incendiary bombs on the city at 1:51 a.m. Raining like hailstones from the inky sky, the heavy ordnance swiftly set off a raging inferno amid Exeter’s dense downtown streets lined with rows of old combustible wooden buildings. Adding to the chaos, agile German bombers soared low over the firestorm, attacking the floundering emergency services with machine gun fire.

By dawn, the scale of the damage had become chillingly clear: 156 people were dead, 563 were injured and 400 shops and 1,500 houses had been destroyed. In total, 30 acres of Exeter lay in smoldering ruins.

“Exeter is the jewel of the west,” trumpeted German radio later that day. “We have destroyed that jewel, and we will return to finish the job.”

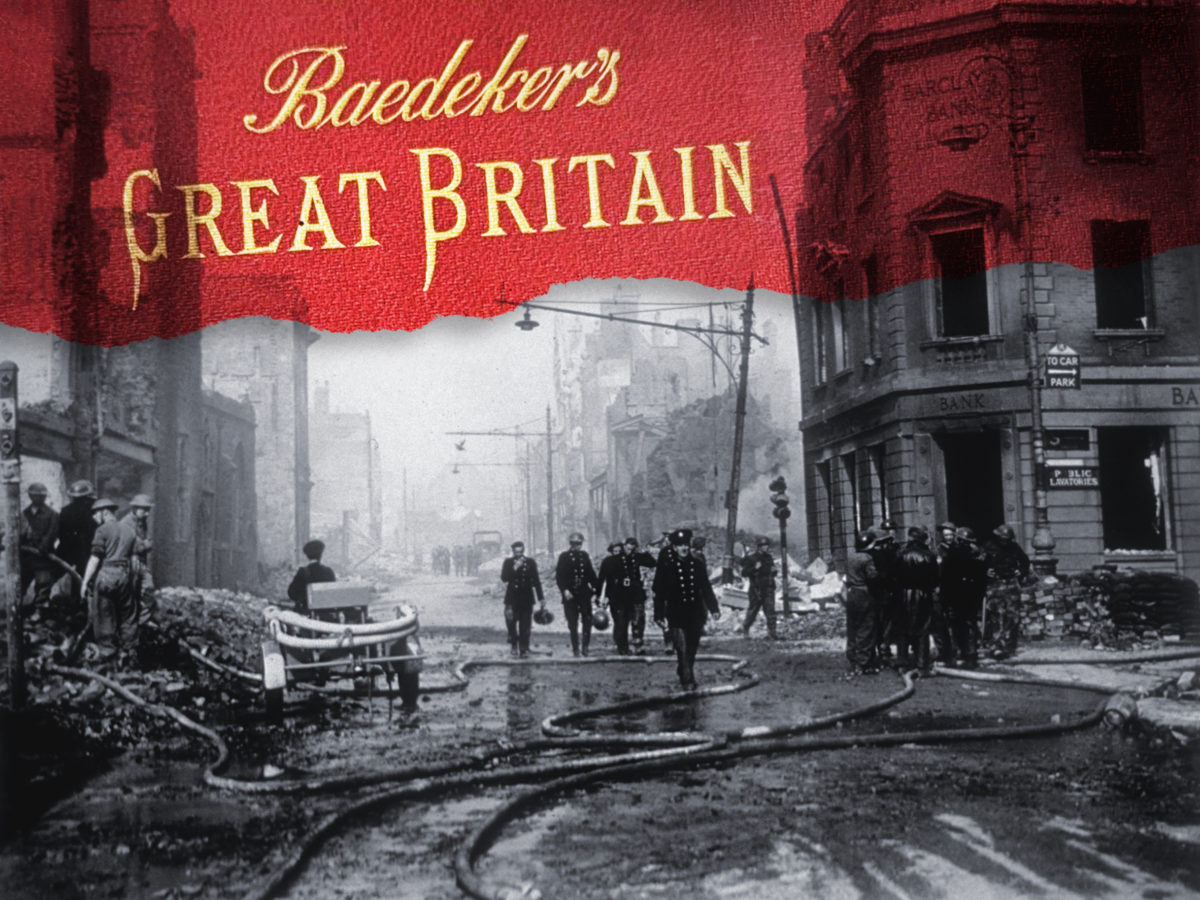

It was a harrowing message that characterized a new era of cultural destruction in World War II. Exeter, a town with a long history in the wool trade crowned by a magnificent Norman-Gothic cathedral, was of no military or strategic importance. Instead, it had been targeted in retaliation for a British air attack on the historic north German city of Lübeck five weeks earlier. In a petulant tit-for-tat exchange, the Nazis had — purportedly — chosen Exeter because it featured prominently in a 1937 edition of the German-produced Baedeker guidebook to Great Britain.

“We’ll go out and bomb every building in Britain given three stars in the Baedeker,” declared Gustav Braun von Stumm, deputy head of the press arm of the Nazi Foreign Office, in a statement on April 24, 1942. Thus began a chapter of the war that became known as the Baedeker Blitz.

Guidebooks to Light the Way

In the early years of international travel before World War II, the idea of using a tourist guidebook to plan devastating bomb attacks would have seemed insidious and far-fetched. Baedekers, the most respected and iconic travel tomes of the era, were designed for peace-seeking explorers rather than military strategists.

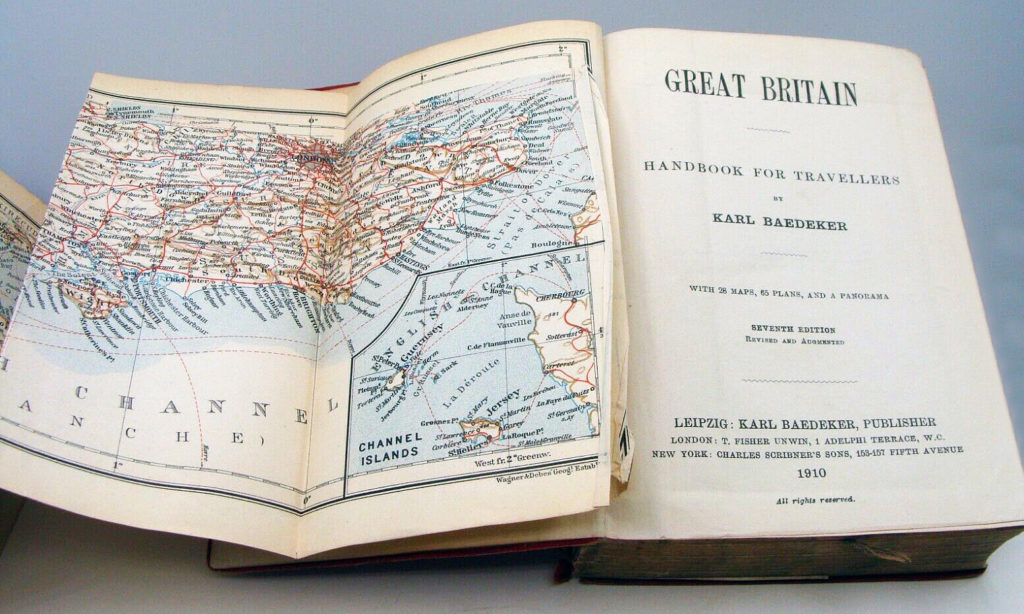

Founded inauspiciously by German publisher Karl Baedeker in 1827, the fledgling book company gradually morphed from a small family concern into a hugely successful business that published guides in multiple languages, including English. By the early 20th century, the distinctive volumes with their red jackets and elegant gold lettering covered countries as diverse as Spain and India and were renowned for their exhaustive research and meticulous maps. Karl, who had been affectionately christened the “father of modern tourism,” died in 1859, but his sons and grandsons stepped into his shoes and carried on the family legacy.

During a protracted golden age starting in 1900, an astounding 233 Baedekers were published in fewer than 15 years. Fueling an emerging tourist industry, the indispensable guides were name-checked in works of literature and mined by eminent archaeologists of the era. E. M. Forster incorporated them enthusiastically into his novel “A Room with a View,” T. S. Eliot mentioned them in an abstract poem, and British writer and military leader T. E. Lawrence (better known as Lawrence of Arabia) referenced them during excavations in the Middle East. By the 1920s, the term “to baedeker” had become a synonym for “to travel.”

However, the firm’s reputation for accuracy and unbiased opinion was given a serious jolt after the rise of Hitler. From the mid-1930s onward, the Nazi propaganda machine began to heavily vet Baedeker guides, editing their history sections and adjusting widely accepted facts to suit Nazi ideology. In 1936, the company produced a special book for the Berlin Olympics that promoted the views of Hitler’s regime, and, in the early 1940s, they were commissioned by Hans Frank, head of the Reich’s administration in occupied Poland, to write a guide to the German-run territory. Among the book’s questionable commentaries, it portrayed Polish Krakow as a historically German city, referenced whole areas to be “free of Jews,” and identified Auschwitz as a train stop.

Things took a more nefarious turn during World War II when a German general admitted using a Baedeker guidebook to help draft plans for an important military operation. In February 1940, General Nikolaus von Falkenhorst was given little more than a day by an impatient Hitler to pad out the details of Operation Weserübung, the upcoming invasion of Norway. “I went out and bought a Baedeker, a travel guide, in order to find out just what Norway was like. I didn’t have any idea,” the general later told the tribunal at Nuremberg. Five hours after making his book purchase, and with the help of some typically precise Baedeker maps and directions, von Falkenhorst had enough information to give the Fürher the plan he wanted.

It was a harbinger of things to come.

A Lull in the Bombing?

By 1942, the Blitz — the Luftwaffe bombing campaign that for nine months in 1940 and 1941 had rained down on Britain’s largest cities, with London bearing the brunt of the storm — had entered a relative lull. Running against the flow of events, the Lübeck raid in March marked the first time the Royal Air Force had bombed a German city with force and precision, resetting the unofficial rules of air combat in northern Europe.

Lübeck was a beautiful Hanseatic city with an old medieval core on the Baltic Sea. Its strategic value was limited. But as the war stretched into its third year, the British Air Ministry, seeking to turn the tide in the conflict, issued a new “Area Bombing Directive” on Feb. 14, 1942. Orders were dispatched to Bomber Command, headed by the pugnacious commander-in-chief, Arthur “Bomber” Harris, to hit German factories and industrial areas but also to “focus attacks on the morale of the enemy civil population.” If the people saw their ancient buildings and grand cathedrals burning, the ministry reasoned, it would seriously affect their support for the war.

It was a novel but flawed argument. While the Lübeck raid flattened many priceless monuments and left more than 300 civilians dead, it did little to dampen German spirits, perhaps because the country’s cities had suffered little in the war so far. Furthermore, reprisals were swift. In mid-April, Hitler widened the scope of the German Blitz to include terror attacks directed at civilians and cultural sites. Up until then, Luftwaffe bombings had primarily targeted Britain’s key ports and industrial centers. London, Liverpool, Hull, Southampton, Glasgow, Belfast and Coventry had been hit throughout 1940 and 1941, but after Lübeck, the course of the campaign noticeably shifted.

Selecting their new targets with the utmost care, the Germans opted to hit an attractive assemblage of historic English cities with substantial firepower. Ominously earmarked for bombing raids were placid Exeter, Georgian Bath, medieval Norwich, Roman-founded York, and the cathedral city of Canterbury, the inspiration for Geoffrey Chaucer’s seminal “The Canterbury Tales.”

To what extent military planners dipped into the Baedeker guide to Britain to procure their on-the-ground intelligence is uncertain. The loose-tongued Gustav Braun von Stumm had quickly been reprimanded by Joseph Goebbels after his unscripted Baedeker remarks. The German propaganda minister was incensed that his fellow press agent had publicly alluded to hitting cultural targets. Von Stumm’s reference to bombing “three-star” buildings wasn’t even accurate. Baedeker guidebooks only awarded a maximum of two stars to city sights in the 1940s, and many of the locations the Luftwaffe ended up bombing (including Exeter Cathedral) had one-star ratings.

Notwithstanding, the five cities chosen by the Germans to be unceremoniously blitzed shared a wealth of historical heirlooms listed in the Baedeker guidebook, from Norwich’s 12th-century cathedral to York’s medieval walls. Not expecting attacks from the air, urban defenses in these non-industrial population centers were poor, with few of the protective antiaircraft emplacements and barrage balloons common in London and other big cities.

The attacks were designed to inflict maximum damage. Organizationally, they involved up to 80 aircraft flying two sorties per night, mostly heavy Junker Ju-188 bombers mixed with some lighter Dornier Do-17s. Kampfgeschwader 2 and several other units from Luftwaffe Air Fleet 3 were tasked with undertaking the deadly missions, flying out of bases in northern France.

(Bundesarchiv Bild 183-L21844)

Exeter was the first place to be hit on the nights of April 24 and 25 when, despite poor visibility, it was “softened up” with an initial spate of low-level bombing before the Luftwaffe returned to ignite its deadly firestorm on May 4.

Bath was the next victim, with three raids spread between April 25 and 27. The city suffered abnormally high casualties (417 killed) mainly because its citizens assumed that the incoming bombers were heading toward the larger, more strategic port of Bristol, 13 miles away, and failed to take adequate protection. The city’s elegant Georgian Assembly Rooms saw the most high-profile damage. Their interiors were so badly burned out that postwar repairs took more than 20 years to complete.

Norwich suffered two devastating raids on April 27 and 29, and while its famous cathedral emerged mostly unscathed, over three-quarters of the city’s houses sustained some level of damage. York got off more lightly, although there were still 79 listed deaths, and the medieval riverside guildhall was gutted.

Canterbury was hit a month later, in early June, in three separate raids. Miraculously, its cathedral — an ancient pilgrimage site — survived, although 800 other buildings were destroyed and 43 people lost their lives.

As spring turned to summer, the true cost of the Baedeker raids became clear: 1,637 killed, 1,760 injured and over 50,000 houses destroyed, not to mention losses of irreplaceable heritage, some of it dating back centuries. But German losses were also high (approximately 40 aircraft were lost over the summer) and Britain’s Bomber Command was quick to retaliate.

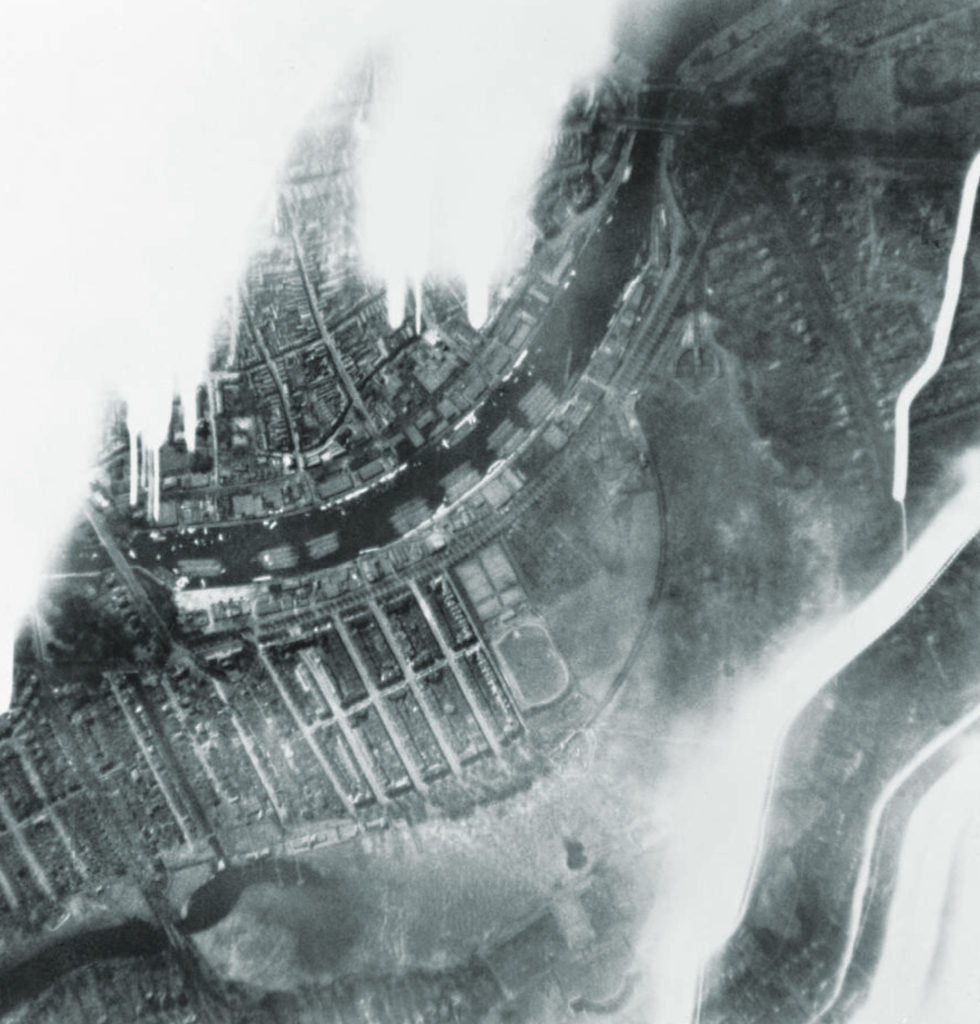

On May 31, 1942, the RAF caused substantial damage to the cathedral city of Cologne on the Rhine River in the first of what became known as the “thousand bomber raids.” The pummeling of Cologne dwarfed any individual strike in the Baedeker Blitz, taking the lives of 462 civilians, making 58,000 homeless and destroying 61 percent of the urban area — all in a single night.

By July 1942, the wave of German bombings had noticeably simmered. But, although the worst may have been over for Britain’s cities, the Baedeker Blitz didn’t cease overnight. Germany’s targeting of cultural sites continued, albeit with less precision and intensity as the tide of the war began to turn against the Nazis. Throughout 1942-43, the Luftwaffe revisited Canterbury, hit the market town of King’s Lynn in East Anglia and caused damage to the south coast seaside resorts of Hastings, Eastbourne and Bournemouth, among others. However, by 1943, German forces were having to deal with existential threats elsewhere, most notably on the Eastern Front and in North Africa. Soon, RAF bombings exceeded those meted out by the weakened Luftwaffe in both regularity and damage. Furthermore, the British had had time to reinforce their ground defenses and offer protection to their most vulnerable cities.

While the Baedeker raids of 1942 marked a notable shift in wartime tactics, they ultimately did little to achieve their main goal: to seriously dent the morale of the British population. There was plenty of material damage and a tragic number of deaths (although far fewer than the 43,000 who perished in the 1940-41 Blitz). Exeter saw the heart torn out of its city center, losing its main library, the architectural masterpiece of Bedford Circus, numerous churches and a choral school. Norwich’s railway station was reduced to rubble, and Bath lost two iconic churches. But by 1944, the Germans were starting to see more losses than gains. With their air force considerably weakened vis-à-vis the RAF, they lacked the manpower and will to continue with the costly bombing campaign.

Keep Calm and Carry on

Rebuilding after the raids once the war was over was a complicated and lengthy process that stretched into the mid-1960s. It wasn’t all bad news. By luck, divine intervention or exceedingly good craftmanship, all the cathedrals in the targeted Baedeker cities escaped with minimal damage. Exeter Cathedral lost St. James’s Chapel courtesy of a single high explosive bomb; Canterbury lost a library on the cathedral precinct; and Norwich cathedral was saved by the brave and speedy actions of its firefighters. While many other historic buildings collapsed or were so badly damaged that they had to be demolished, plenty more, such as York Guildhall, were successfully restored.

Today, while the rebuilding might be over, the danger hasn’t completely evaporated. Hiding beneath the surface, unexploded ordnance continues to bring back echoes of a distant conflict. As recently as February 2021, 2,600 homes in Exeter had to be evacuated to allow for the controlled detonation of a 2,200-pound bomb that had lain dormant for nearly 80 years.

Bad for business

As for Baedeker, the war, not surprisingly, wasn’t good for business. In an increasingly dangerous Europe, tourism flickered out and the books were little used after 1939. The 1940 guide to Holland was null and void before it was even published, thanks to the Nazi invasion of the Low Countries, while the 1943 Baedeker guide to occupied Poland (which recommended that readers bring a gun for nighttime driving) had few takers. Calamity arrived in December 1943 when Baedeker’s Leipzig headquarters was destroyed in an RAF bombardment that wiped out the firm’s entire archive. However, in common with the British cities that had once been bombed in its name, the company diligently regrouped and rebuilt. In 1949, Karl Friedrich Baedeker, great-grandson of founder Karl, published the first postwar Baedeker, a guide to the northern German states of Schleswig-Holstein. In 1951, the firm restarted publishing guidebooks to London. The book series survives to this day, albeit under different ownership. It has since been usurped in sales and influence by more modern brands such as Lonely Planet and Fodor’s.

While the Baedeker Blitz has never been repeated, World War II wasn’t the last time military personnel tapped guidebooks for planning purposes. During the 2003 Iraq War and its aftermath, the U.S. military purportedly used Lonely Planet’s Middle East guide for information on the economy, government and important embassies and buildings. “It’s a great guidebook,” reflected U.S. ambassador Barbara Bodine several years later, “but it should not be the basis of an occupation.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.