Major conventional warfare seems to have gone out of style. Strategic analysts peering into the future see wars with shadowy “non-state actors” like al-Qaeda, or international crime syndicates like the Zetas in Mexico, or even pirates plying the waters off the Horn of Africa. I know a lot of people in the defense community, and I’m not giving away secrets when I say that is very much how they view things. More and more, the U.S. Army casts its future in terms of “building partner capacity”—helping poorer countries defend themselves against terrorism or natural disaster.

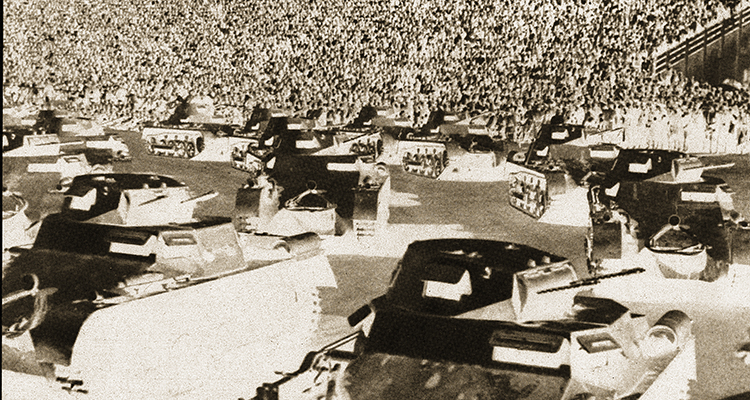

Recently, though, a strange thing happened on the way to the future. Political crisis erupted in Ukraine, Russia seized Crimea after protests by Russian nationals living there, and now all Ukraine seems to be threatened by its larger neighbor. The headlines seem out of place, even shocking, in our post-Cold War world: a chest-thumping dictator, tanks massing at the Ukrainian border, enemy forces threatening the Donbas—the heavy industrial districts of Eastern Ukraine. The headlines read like something out of 1939 or 1940.

Of course, this magazine’s readers have probably never been taken in by notions of eternal peace, the abolition of conventional warfare, or of a world so globalized that war between major players would be economic suicide for everyone concerned. You are a savvy bunch and you know that these ideas were common in the 1930s—a time, like our own, when the international financial system came close to collapsing, and when serious economic doldrums seemed unshakeable. War made little sense then, either, and yet a war broke out—one that rocked civilization to its foundations.

The 1930s saw dictators posture and strut, armor mass on borders, and demands arise for boundary rectification. Adolf Hitler’s ultimatum to Czechoslovakia to hand over the Sudetenland—where ethnic Germans were clamoring to unify with Germany—nearly led to war in 1938. It would have, had the western powers not abjectly surrendered at Munich.

Next, Hitler demanded Poland yield access across the “Polish corridor” and return Danzig, heavily German but a Free City administered by the League of Nations and meant to give Poland a port. This time, Britain and France hung tough. They had guaranteed Poland’s security if Germany invaded, and when Germany did so, the western powers declared war on Germany and World War II was on.

You don’t have to read deeply to see the similarities. Ethnic Russians live all over the countries unshackled when the U.S.S.R. crumbled: Ukraine, Moldova, Belarus, the Baltic states. If dispossessed Russians have real grievances, Russia can exploit them. If they don’t, Russia can foment them. And some potential targets, like Estonia, already have a security guarantee from the West. It’s called NATO.

I’m not predicting World War III, and if I were, then you should be backing away slowly; historians make terrible prophets. But this situation should serve as a reason to keep studying World War II. Note how little issues can mushroom into global violence. Take the current U.S. strategic “rebalancing”—moving military resources away from Europe and toward the Pacific—with a grain of salt. Events have a way of upsetting the best-laid strategy. Europe hasn’t had a major land war in 70 years, but that is not the same thing as saying it will never have another. And Europe still matters to U.S. security.

And yes, perhaps it might be a good idea to keep some supposedly obsolete heavy metal—M1 tanks and M2 Bradleys and F-16 strike aircraft—oiled and ready. The maniacs of al-Qaeda are still lurking out there, wishing us harm, and the military needs to go after them in its own way. But who knows what else is out there, ready to plunge the world into war? If World War II taught us anything, it’s that you can never predict the day or the time.

Originally published in WWII magazine’s July/August 2014 issue.