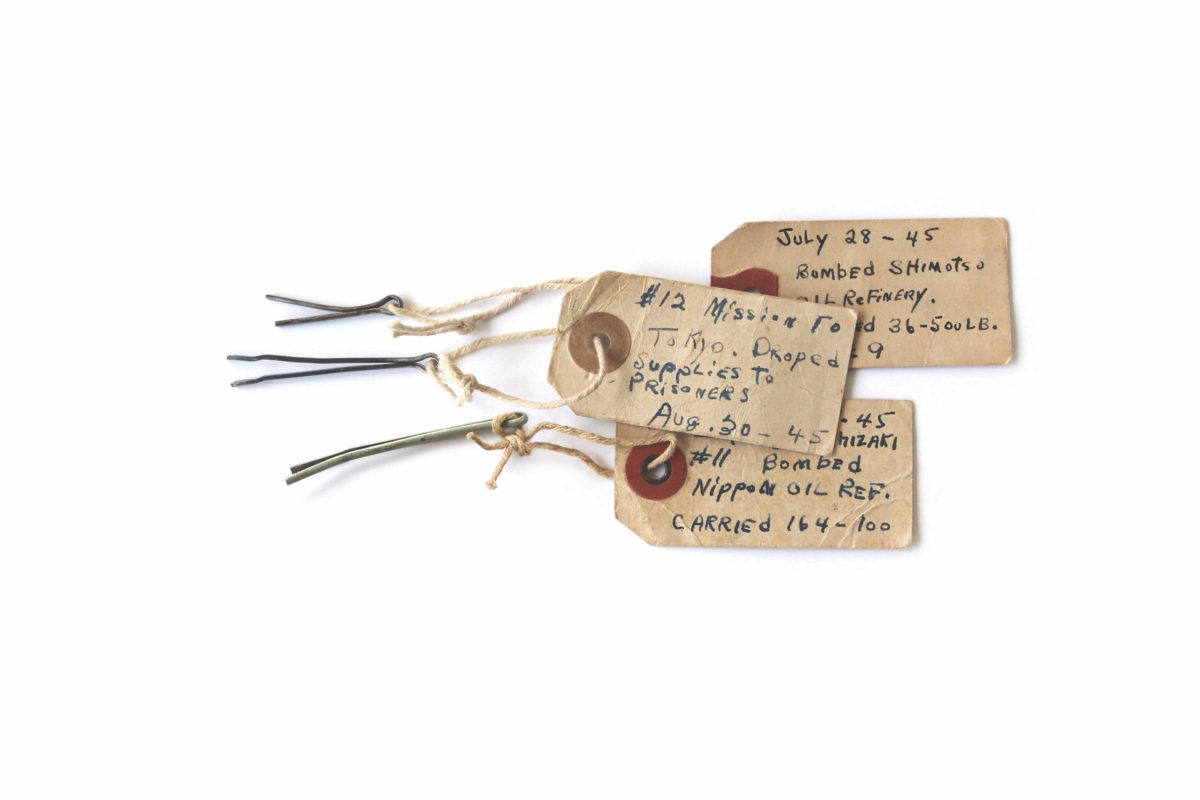

My father, Sherman Oxendine, was a B-29 tail gunner flying missions over Japan in the last months of the war. He kept a collection of bomb-arming pins, all labeled with the target, date, and bomb load—but there’s one I’m especially curious about. One of his tags indicates a supply drop for prisoners. Why would there have been a bomb pin for that kind of drop?

—David Oxendine, Huntsville, Ala.

Needless to say, readying high explosives for flight was deadly serious business. These simple cotter pins, attached to manila tags, fit into a hole in every bomb fuze, physically blocking the firing plunger from inadvertently striking the detonator. Just before flight, ground crewmen rigged another safety device into the system—an arming wire—which disabled the spinning vanes of the fuze until the moment the bomb was dropped. Once the arming wire was installed, the cotter pin could be safely removed from the fuze. As a result, discarded fuze tags commonly littered the bomb bays of American aircraft.

Fliers in both Europe and the Pacific picked up the wayward tags and scribbled the date and target on them, creating a souvenir from each of their bombing missions. These pocket-sized curios became a sort of fragmented diary of a crewman’s combat career. The National WWII Museum and other institutions exhibit sets of tags quite similar to the ones penned by your father.

Once the shooting war ended in the Pacific, B-29 bombers kept flying. But instead of hauling bombs, the aircraft now lugged chow and supplies to 158 prisoner of war camps in Japan and enemy-occupied territories. These airdrops delivered 4,470 tons of lifesaving material urgently needed by men who had undergone years of brutal captivity.

The aircraft of Operation Swift Mercy hefted wooden boxes strapped into bundles and rigged to descend to earth under cargo parachutes. No fuzes, detonators, or bombs were involved. So why the extra fuze pin in your father’s collection? By this time—what would be his 12th trip to Japan—your father was invested in tradition. If he didn’t find a way to commemorate this final operation, he’d always be one tag short.

There was another reason, too; your father’s humanitarian flight to the Tokyo area on August 30, 1945, was still, technically, a combat mission. Even with little chance of encountering enemy flak or fighters, every grueling and dangerous Superfortress flight over thousands of miles of water flirted with calamity. As a result, up until the moment the surrender documents were signed a few days later, on September 2, every B-29 crewman who made the flight got credit for a “combat mission”—even if they were delivering clothes, medicine, and meals instead of TNT and napalm.

Your father most likely picked up a discarded tag from an earlier offensive operation and inscribed it with all the pertinent data for his August 30 mission of mercy, thus telling the story of each and every one of his precarious assignments, including the last. —Cory Graff, Curator

Have a World War II artifact you can’t identify?

Write to Footlocker@historynet.com with the following:

— Your connection to the object and what you know about it.

— The object’s dimensions, in inches.

— Several high-resolution digital photos taken close up and from varying angles.

— Pictures should be in color, and at least 300 dpi.

Unfortunately, we can’t respond to every query, nor can we appraise value.