In August 1943 members of the highly classified Wright Project departed Virginia’s Langley Field for service in the South Pacific. Ten Consolidated B-24D Liberator bombers—equipped with an untried combat electronics system and designated SB-24s—and their handpicked crews were off to join the Thirteenth Air Force, then battling the Japanese in the Solomon and Bismarck Islands. The project’s leader, Colonel Stuart “Stud” Wright, had a letter in his breast pocket with the letterhead of U.S. Army Air Forces Headquarters, signed by no less a person than Commanding General Henry “Hap” Arnold. The Arnold letter instructed all commands to help the unit deploy as soon as possible and provide all necessary support.

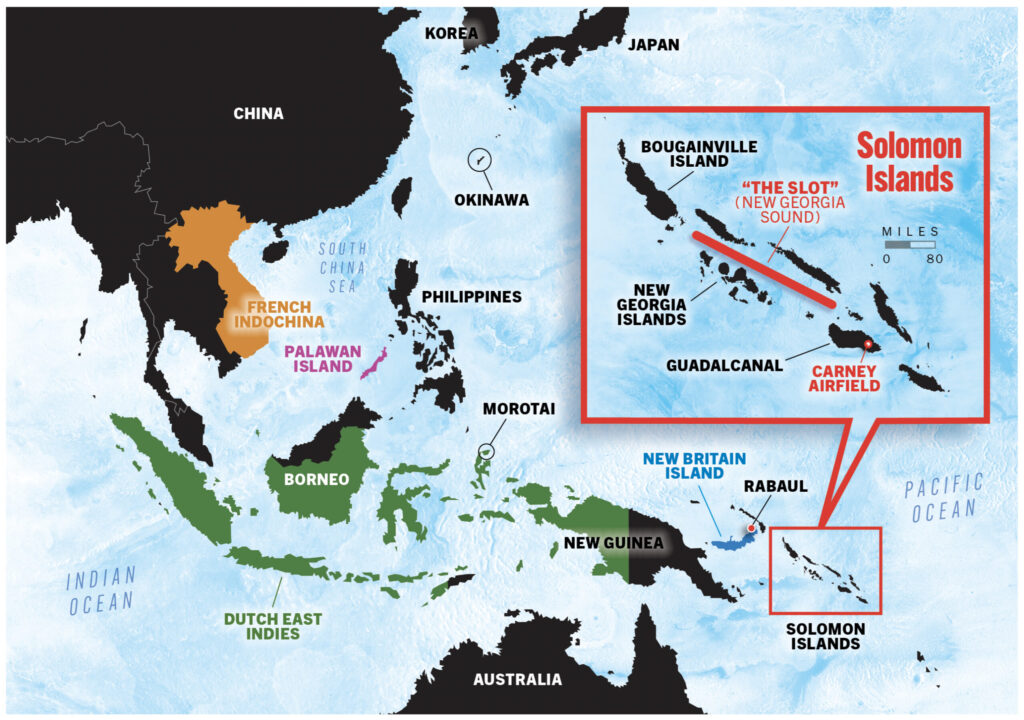

Wright and his team touched down at Guadalcanal’s Carney Field on August 23, 1943, and, initially designated as the 394th Bombardment Squadron (Heavy) of the 5th Bomb Group, flew their first combat missions three days later. Before long the Wright group became known as “the Snoopers.”

The project’s ten crews—100 officers and men—and aircraft intended to prove the combat effectiveness of an electronics system devised by Radiation Laboratory, a research and development team of civilian scientists and engineers at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge. Working closely with the 1st Sea Search Attack Group at Langley Field, the lab’s technology would allow an aircraft to fly into to the blackness of night, spend 10 or more hours hunting over large swatches of enemy-dominated ocean, detect targets at great distances, and home in on them with precision low-level attacks. A single nightstalking aircraft could seek prey from 5,000 feet or more, then drop to a thousand feet or less to strike, unseen by the target vessel until the bomb blasts lit up the night. The attacking aircraft would then speed away to return home safely at daybreak.

While good intelligence frequently suggested where the SB-24s should look for its targets, just as frequently an aircraft’s advanced microwave search radar detected enemy ships from distances of 50 to 70 miles. A competent operator could use the SCR-717-B radar to position the attacking aircraft for an out-of-the-night run, catching a moving target with a bomb spread triggered by the onboard APQ-5 computer that allowed a precision release of a string of 500-pound bombs.

But these low-level attacks took their toll on the unit as the enemy fought back. And while Colonel Wright had warned his men that many would not return, the loss of two of the 10 original crews within a few weeks would be sobering.

Although Wright’s men had been attacking targets almost every night from the day of their arrival, the first really “big show” occurred on the night of September 28-29, 1943. The U.S. Naval Intelligence Group alerted ComAirSols, the Guadalcanal-based command that coordinated and directed all air operations in the South Pacific at the time, that a Japanese resupply convoy, comprising a bevy of fast transports escorted by a half-dozen destroyers, would be making a supply run down “The Slot,” the nickname for the sea passage from Bougainville Island through New Georgia Sound and on to Guadalcanal. ComAirSols tagged Wright and his SB-24s to find, track, and attack the convoy.

Captain Franklin T.E. Reynolds and his crew took the lead in the SB-24 Coral Princess, found the targets, and determined the convoy’s position, course, and speed. Reynolds’ radar operator identified 11 ships and he selected the largest, a cargo vessel, for his attack. The system performed with perfection. Reynolds made a beam-on run at 1,000 feet altitude and 135 knots indicated air speed, and the computer toggled a string of six bombs spaced at 75-foot intervals. The bombs walked across the ship, delivering two direct hits and four near misses. Fires were soon raging out of control, with the flames visible for 20 miles.

Reynolds summoned other SB-24s out that night to join in his attack and they used the fire as a beacon when they arrived. Captain John Zinn and the crew of Uncle’s Fury were next but failed to make any hits as anti-aircraft fire increased. Major Leo Foster, who would take over command when Wright went home to report on the unit’s success, led the second wave into the convoy. Flying in Devil’s Delight with Wright as copilot, he and his crew dropped bombs that just missed a frantically maneuvering destroyer, then climbed atop the action to direct more incoming aircraft. Bums Away, piloted by Lieutenant Bob Lehti, was next into the fight. The SB-24 found a target and started a low-altitude bombing (LAB) run, but Lehti banked away moments before release when the identification-friend-or-foe (IFF) system malfunctioned and signaled that the ship he was attacking was a U.S. Navy vessel. Lieutenant Ken Brown in Ramp Tramp, hearing Lehti communicate that his IFF was sending confusing signals, checked his IFF and also elected not to attack out of concern that the ships were American.

Two other SB-24s soon arrived, delayed because they had to recruit airmen from other aircraft to fill out their crews. Lieutenants George Tillinghast and Fred Martus, each in the aircraft they had brought over from Langley Field, The Lady Margaret and Gremlins’ Haven, rolled in last on the now scattered ships. By this time the Japanese had shaken off the shock of the attack and responded with a heavy volume of fire. Although darkness did hide the SB-24s’ approach, the Japanese were able to pick up the attackers as they made the final run to their bomb release points, making the aircraft highly vulnerable as they passed over their targets.

Martus selected his ship, took the lead, and radioed to Tillinghast, “This is Martus. Have them in sight. We’re going in.” Tillinghast followed Martus into the fight but selected a different ship, which he just missed. He then climbed to 10,000 feet and circled the fires below to establish contact with the Martus crew, these two being the last of the attackers to depart for home. But there was no trace of Martus and the crew of Gremlins’ Haven.

The loss of the Martus crew came in the wake of the crash of Lieutenant Bob Easterling’s Princess Slipp a few weeks earlier. In the early morning of August 31, that SB-24 had reached base badly shot up while attacking Japanese vessels and it had crashed while attempting to land at Carney Field, killing all 10 men on board. The losses hit the project hard. As one veteran remarked some 35 years later, “Now it was personal, the easy times were over.”

As October moved into November, and Admiral William Halsey’s forces fought their way up the Solomon Island chain, the Wright Project SB-24s found themselves not only hunting Japanese shipping but also directly supporting the U.S. Navy cruiser-destroyer task groups that combated Japanese forces determined to disrupt Allied landings in the advance toward Rabaul, Japan’s main naval and air base on New Britain Island.

One such decisive black-of-night encounter between speeding warships was the Battle of Empress Augusta Bay. In this case a powerful Japanese cruiser-led task force attempted to wreak havoc an Allied amphibious landing at Cape Torokina on Bougainville Island. On the night of November 1-2, 1943, the strike force, under Admiral Sentaro Omori, left Simpson Harbor at Rabaul. Its two heavy cruisers, two light cruisers, and brace of destroyers intended to attack the 14,000 men of the U.S. 3rd Marine Division who had splashed ashore earlier that day. Opposing this strike force was a U.S. task group comprising four light cruisers and eight destroyers under the command of Rear Admiral Aaron S. “Tip” Merrill. Every sailor in Merrill’s command knew the Japanese were coming hard at them, steaming for a fight. But they did not know from where they were coming, when they planned to attack, or how many vessels they had.

That evening the XIII Bomber Command sent the SB-24s of Lieutenants Vince Splane and Duward Sumner into the night to patrol separate sectors of New Britain Island’s St. George’s Channel, the most likely path of the Japanese approach. Sumner in Ramp Tramp found Omori first, his SCR-717-B radar detecting the Japanese from 35 miles out. Sumner positioned his plane overhead as his radar operator fine-tuned his scope so he could count the ships, allowing Sumner to radio an alert to provide course, speed, and number of vessels to Merrill’s task group. Sumner alerted Splane’s crew, aboard their favorite squadron aircraft, Devil’s Delight, and Splane closed to back up Sumner. Splane’s radar was performing exceptionally well that night and picked up Omori’s task force at 75 miles. With Splane now joined overhead to continue the tracking mission, Sumner sought and received permission from ComAirSols to attack. Over a two-hour period, Sumner made several LAB attacks, one of which near-missed the light cruiser Sendai. He then turned over the tracking of Omori’s strike force to Splane and Devil’s Delight. In his after-action mission report Sumner noted that issues with his bomb release mechanism affected his attacks. But even Sumner’s failed attempts impacted Japanese plans. Omori, his battle flag flying from the veteran heavy cruiser Haguro, realized he was being tracked. Recognizing they had lost the element of surprise and faced an alerted Allied force, Omori and his headquarters elected to forgo one element of the attack, causing a group of troop-laden destroyers to abort their mission and turn back to Rabaul.

Splane tracked Omori for an hour, radioing updated details to Merrill, who maneuvered his task group to intercept the Japanese. At this point, well after midnight, Devil’s Delight received permission to mount its own LAB run. Splane had his radar operator pick out the strongest radar signature and homed in to deliver “six five-hundred-pound bombs in a 30-foot interval release sequence that walked right up to the side of the ship.” Banking away, Splane knew he had damaged the flagship and rattled its bridge crew. The attack had caught the cruiser by surprise and Splane received no fire from the Haguro on this run nor on a follow-up attack up the wake that just missed the cruiser.

Omori was flustered and confused. He changed course, then reduced speed to assess the damage to his ship and determine the overall situation. He had damage to his hull and, as rain pelted his bridge and scout planes delivered reports of sighting Merrill’s ships, Omori’s tight formation lost needed cohesion. The Japanese soon encountered Merrill’s radar-equipped task group, well-organized and waiting for their enemy. Merrill’s destroyers leaped to the battle and released their torpedoes, as the light cruisers, their radar tracking the Japanese and directing gunfire, maneuvered to gain best advantage.

By four in the morning, it was over. Omori limped back to Rabaul with the light cruiser Sendai sunk, a destroyer rammed and sunk in the battle’s confusion, two other destroyers badly damaged, and Haguro and sister ship Myokodamaged. In the morning, Merrill’s superior, Admiral Thomas Kinkaid, dispatched a special thank you to Halsey at ComAirSols at Guadalcanal for a “splendid night tracking mission.”

The following night, three more SB-24s lifted off into the darkness, this time into the face of a rain squall, to begin the hunt anew. Operating independently of any bomb group and mostly flying single-aircraft missions, these specialized airplanes and their crews continued their fight against Japan for the next 22 months as the unit moved forward across the Pacific. Over time, the 868th Bombardment Squadron, as they would soon be formally designated, increasingly fought during the day, not just at night.

U.S. Army Air Forces Lieutenant Walter N. Low was 21 years old when he took his crew of 10 young men to war in the Pacific in the spring of 1945. They joined the 868thin April when it was based at Morotai, an island in the Moluccas in the Dutch East Indies.

Major Baylis Harriss had been recently appointed squadron commander. A Texan with years of combat experience, he was rebuilding the squadron with additional crews and new aircraft, while pushing his men to undertake longer missions designed to build unit cohesion and confidence.

Lieutenant Low’s first mission occurred on May 6. He and his crew received their baptism of fire attacking the Japanese airdrome at Mandai in the Dutch East Indies. Three days later they hit the Samarinda shipyards on Borneo with the bomber’s normal load of six 500-pound bombs, and three days after that they struck Kendari airfield to crater the runways and keep it unserviceable. They flew five more missions in May, all attacks against shipping facilities, airdromes, and vessels in this same area.

In early June the Low crew kept up this pace, flying missions against many of the same targets in the Dutch East Indies. On June 12, Low and his crew flew to the Flores Sea on a daylight search for shipping, where they found and attacked a collection of small cargo vessels. And on June 18 Low and crew flew as a two-ship mission to hit Oelin Airdrome. Both planes came home with feathered props, having nearly run dry on fuel. On that mission Low had drawn the B-24 Lady Luck II as his airplane. The airplane had arrived in the squadron a few weeks before, already had a dozen missions to her credit, and was regarded by all who flew her as a “solid airplane.”

Late July found the squadron preparing to relocate to Okinawa to join the air campaign against the Japanese home islands in preparation for the planned invasion of Kyushu. The landing on Kyushu, the first of two such operations designed to force a surrender on the ground in Japan, was scheduled to occur sometime in late October or early November of that year. It was assumed that the period of August to November 1945 would be one of intense combat for the 868th above and around the four home islands, where Japanese resistance would be fierce. But as the ground elements of the squadron packed their equipment to head north in July, the combat crews of the 868th still operated in the Dutch East Indies.

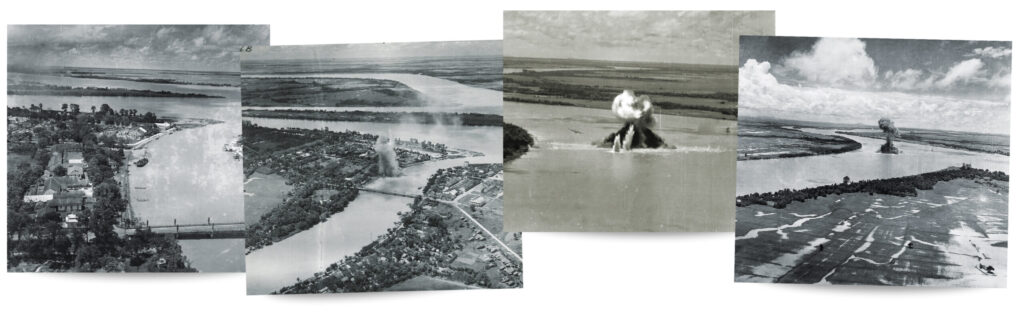

That third week in July, higher authorities directed the squadron to strike farther west to hit targets in French Indochina. Their mission was to search and destroy Japanese shipping along that coast to block the flow of any oil or military supplies to the home islands. Lieutenant Low, in the company of three other squadron aircraft commanded by Lieutenants Mel Jensen, Hensen Sprawls, and George Koonsman, hunted at low level on July 21. The mission was a long one, with the four aircraft departing home base at Morotai before daylight and staging through an advanced airfield on Palawan Island in the Philippines to extend their range. Reaching the French Indochina coast at midday, they discovered shipping targets aplenty, most sheltering in the harbors or slightly upstream in the rivers. This was virgin territory, at least for the far-ranging 868th SB-24 Liberators, and the four hunters made the best of it, bombing and strafing several small merchant ships. One of the mission crews flew inland and destroyed a railroad bridge. The four aircraft returned safely to home base, holed by ground fire but suffering no casualties.

On this day, Low and his crew followed an 868th tradition of attacking at a very low level, bombing from 500 feet or below, then following up with multiple gun runs at 200 feet or less, skimming the water to fire into the sides of vessels with sustained bursts from their .50-caliber weapons. Unlike the dark-of-night LAB missions that had placed the 868th in a league of its own, and to which the unit would soon return in the campaign over the Home Islands, these missions were all by daylight. The hunting Liberators were seen by the vessels they attacked and the result was often a ship-to-airplane shootout.

Two days later Low reprised his visit to the French Indochina coast on his twentieth combat mission, on this occasion in aircraft 808. When he spotted a large tug dragging two oil barges on the Bassac River, Low rolled in to make a bombing run, pushing his luck at a mere 200 feet in altitude. Three 500-pound bombs hit dead center and the barges exploded in a massive fireball, with orange flames shooting into the sky and a dense plume of smoke rising in a mushroom cloud to 1,500 feet. Although his bombs were fused to delay for four seconds to allow an attacker to drop at low altitude, the detonation of the bombs and their target rocked the aircraft. As it came off the target, veteran squadron ship 808 had its waist windows blown out and the airframe twisted. Low was thrown from his seat and landed on the flight deck.

Low reclaimed his seat and he and copilot Don McDermott struggled to regain control of their crippled plane. But serious damage had been done and the aircraft was doomed. A few miles out, over open waters and headed home, number two engine burst into flames and had to be feathered. A fuel leak made it clear that the aircraft could not make it to Palawan, and a decision was made for the crew to bail out. Koonsman flew alongside Low and maintained communications with him, while managing to contact a U.S. submarine in the area. After confirming an emergency rendezvous with the rescue sub, the 10-man crew of Low’s airplane prepared to bail out. Low reached the pick-up point and made three runs over the location as all crew members safely parachuted. Low was the last to jump.

The following day, Lieutenant Sprawls set out on the same course, staging again from Palawan, to search for the missing crew. By then it had become certain that the submarine had not picked up the missing airmen and that Low and his men were adrift somewhere in the South China Sea. Three of the crewmembers managed to survive and were rescued after several days in the water. The other seven perished. Walter Low one of those who survived.

In July 1945, the squadron lost a total of 21 officers and men missing in action and saw its roster reduced to 13 combat-qualified crews and 12 aircraft. But new crews were reporting in, and new aircraft were arriving to replace losses. Importantly, the increased operational tempo established by Major Harriss was the highest ever reached by the unit and this achievement was recognized by the Far East Air Forces leaders. The squadron was now primed to complete its move north to join the final campaign of the war and was ordered to relocate to Okinawa in the final days of the month. The 868th would begin operations over the home islands in early August 1945, well prepared for a war that all assumed would extend into the summer of the following year, if not longer.