“I was never a talker, even with my crew. But I’d try to do the best I could to get back to base.”

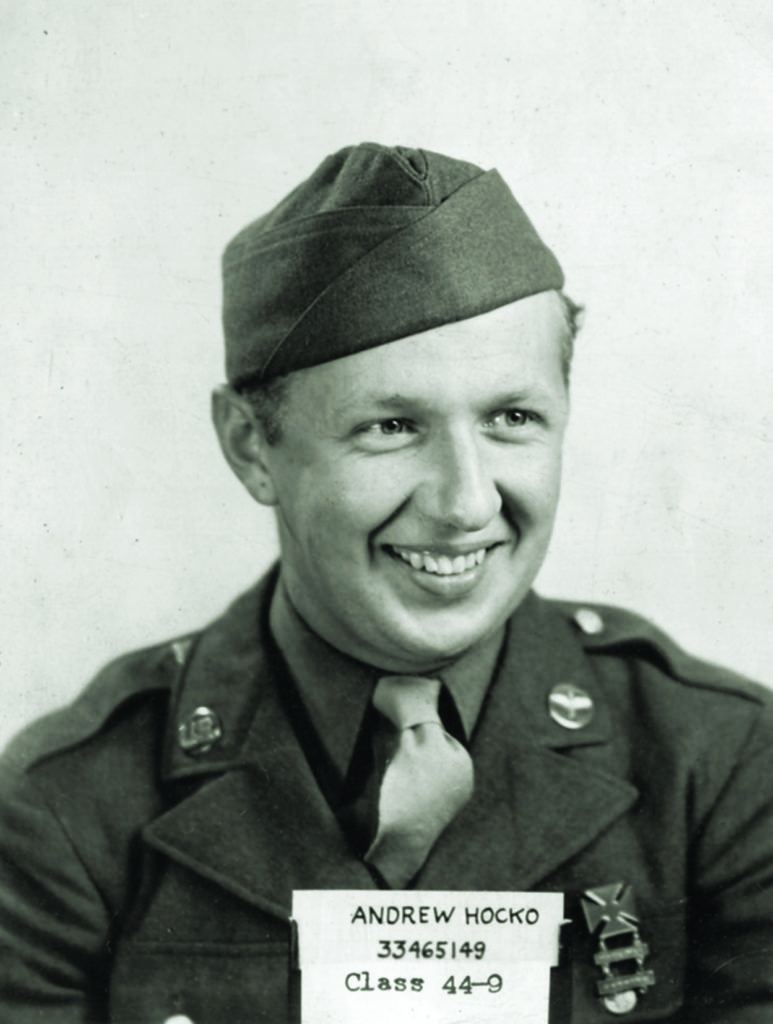

Andrew Hocko Jr., the son of Slovakian immigrants who settled in Scranton, Pennsylvania, coal country, was a waist gunner aboard Double Trouble, a B-24J Liberator bomber that took off from Pandaveswar, India, on February 13, 1945. Joined by five other bombers from the Tenth Air Force’s 493rd Squadron, 7th Bomb Group, Double Trouble winged southeast over Calcutta and the Indian Ocean before turning east en route to the jungled borderlands between Burma and Thailand. The low-level, “in-and-out” mission would take 15 hours—assuming they returned safely.

The B-24s’ objectives were two railroad bridges—one steel-and-concrete, the other a rickety wooden trestle—spanning the Mae Klong River near Kanchanaburi, a town in western Thailand. The structures were two among hundreds of bridges punctuating the Japanese-engineered 258-mile “Death Railway”—the construction of which claimed the lives of 16,000 Allied POWs and 100,000 Asian conscripts.

A 1952 novel and 1957 movie, The Bridge on the River Kwai, depict a fictional commando raid on a wooden bridge spanning a different, smaller river. However, to memorialize the Death Railway and promote tourism, local authorities now designate Kanchanaburi’s stretch of the Mae Klong as the “River Kwai.” Today these particular bridges (rebuilt since World War II) hold strong symbolic meaning. But in 1945, to Andy and his Double Trouble crewmates, they were little more than coordinates on a map.

During a conversation last November, Andy—who turns 96 in May and is retired from a 30-year records management career at the U.S. Information Agency and residing in Maryland—recalled his World War II odyssey from Scranton to Pandaveswar and a celebrated bombing mission.

How did your war begin?

I was a small guy—97 pounds—when I was drafted in 1942 after graduating high school. I went to Atlantic City [New Jersey] for basic training. The motel we stayed at was right on the beach. The next thing I knew I was going to Elizabeth, New Jersey: the Signal Corps. I was a lineman. I climbed the poles to work on power lines.

But you made it to the Army Air Forces.

I think I was out in California [with the Signal Corps] when I signed up; I wanted to see if I could get in. I ended up in Amarillo [Texas] for more training.

You practiced gunnery from the back seat of a training aircraft. Tell me more about that.

We shot at [aerial target] balloons. [The pilot would say] “Shoot,” so I did. Afterward he would say, “Finished shooting? OK, hold on….,” and back down we’d go. I qualified as a ball turret gunner for the bombing unit I joined—the 493rd Bombardment Squadron—stationed in the Mojave Desert.

Tell me about flying aboard the B-24 to India.

The B-24 was noisy. We flew out of New Jersey in September 1944. Then to New York, Connecticut, New Hampshire, Nova Scotia, the Azores, Algiers, Cairo. When we got to Karachi [now part of Pakistan], the engineer got malaria, so I had to take over [as engineer]. My first mission was actually not with my crew. I was a tail gunner with another crew for a bombing mission to Bangkok. Over Burma, on the way back, a plane flew by. It was a Japanese observation plane; he waved at me, so I waved back to him.

What types of missions did you end up flying aboard Double Trouble?

We would most always bomb railroads, railroad bridges: medium-elevation bombing missions at about 2,000 to 3,000 feet with regular bombs. We had 297 hours of bombing missions. Once we flew to China to deliver gasoline, so I spent Christmas 1944 in China.

These were long missions without protection from fighter escorts. How dangerous were they?

The only thing we faced over the target was light antiaircraft fire—machine guns. We removed the ball turret after a couple of months because we had no enemy plane activity. When our nose gunner spotted antiaircraft fire, he opened up. I was now a waist gunner, and I used a camera to take pictures of our missions.

Were you operating the camera during the February 13 mission against the bridges across the Mae Klong River?

Sometimes we had the camera, sometimes we didn’t; this time I had the camera. They told us, “No testing the camera until you’re in a mission.” I’m sitting on the floor. A hatch door near the back of the plane was open. I tried to take a picture when the bombardier said: “We dropped the bombs.” I even saw where the bomb dropped. I pushed the camera “trigger;” it wouldn’t work. I shook the camera handle. Next thing, the tail gunner said, “The bridge is down.” So, I took the camera and tried it once more. And that’s when I took the picture.

That was a pretty hectic and consequential mission. Are there any others that stand out to you?

One time an enemy bullet came into the bomb bay. It hit a terminal [and loosened some wires]. I knew one of the wires connected to a fuel transfer pump. I got out my pliers, traced the wires, and spliced two ends back together.

So, without that connection, you wouldn’t have enough fuel to get back. How does that make you feel now?

Well, I’m alive. I was able to do what I had to do. I was never a talker, even with my crew. But I’d try to do the best I could to get back to base. That’s what I was interested in: getting back safely. ✯

This article was published in the June 2020 issue of World War II.