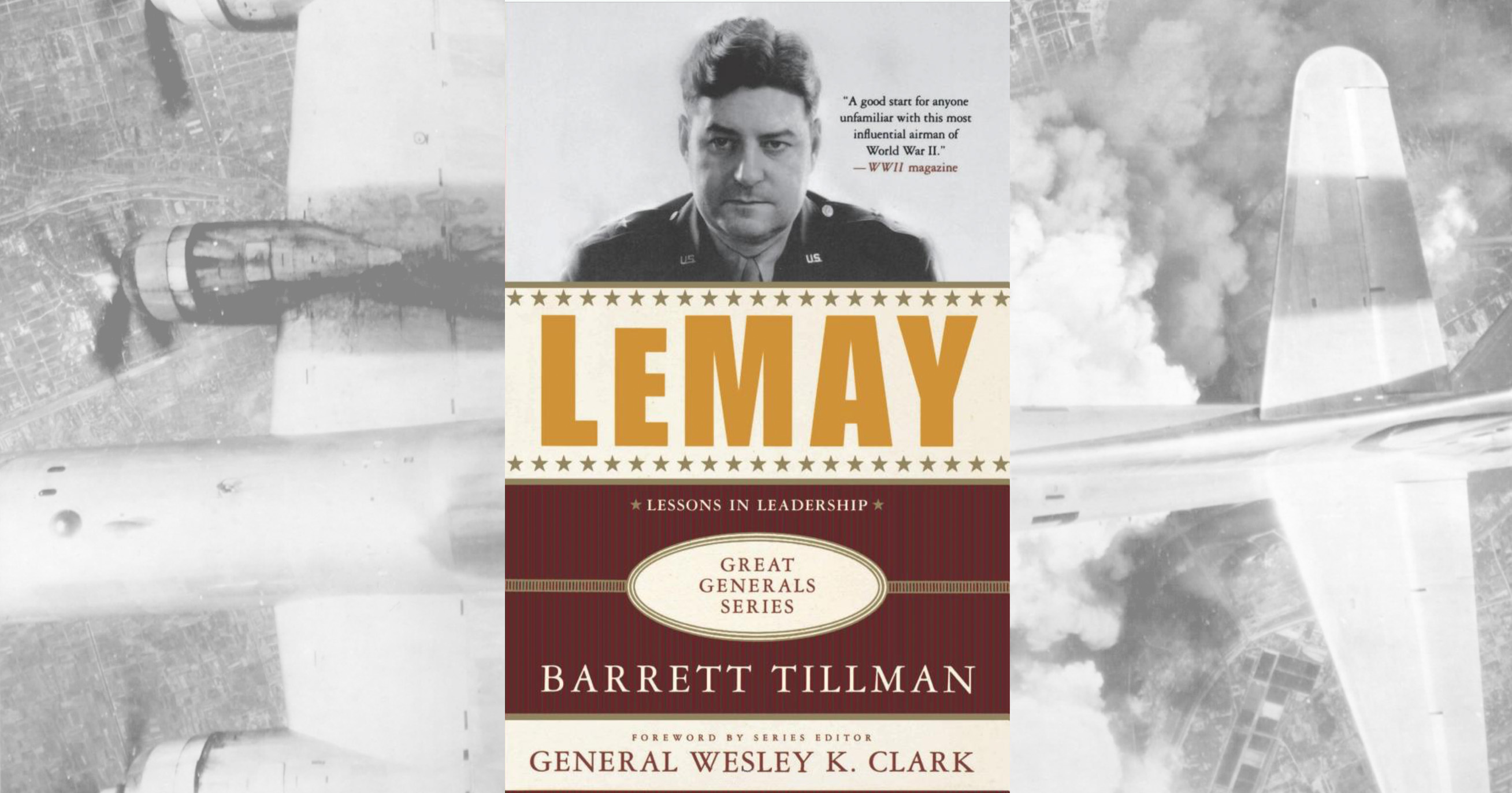

LeMay by Barrett Tillman,(Palgrave-Macmillan, New York, 2007, $21.95)

One day in the 1980s, former U.S. Air Force radar specialist Sam Korth met retired General Curtis E. LeMay at an airshow and asked him if a popular story about him was true. Had the World War II bomber leader actually smoked one of his favorite Cuban cigars while standing under the wing of a Convair B-36, and been warned that the massive Peacemaker might explode? The general had reportedly responded, “It wouldn’t dare.” LeMay grunted, then told Korth: “I started that story. But I always followed my own orders.”

That apocryphal incident reflects the rough-hewn spirit of Curtis Emerson LeMay: an innovative self-starter, a stern advocate of training and discipline, and a direct, candid man with minimal charisma. Yet LeMay was warmly regarded by those who knew him best, and colleagues spoke of his “heart of gold” and “great feeling for the troops.” As one subordinate noted, “Curt LeMay irritated many people, but he usually ended up right.” Major General Ira C. Eaker, second commander of the Eighth Air Force during WWII, described him as a “today general” and his best combat leader, while the equally legendary General James H. Doolittle believed LeMay was probably “the best air commander the United States or any other nation ever produced.”

The life story of Curtis LeMay, a highly decorated air commander who led from the cockpit and listened far more than he spoke, unfolds in LeMay, a finely balanced and insightful biography by Barrett Tillman. He has done a masterful job of portraying the complex, controversial airman whose career has been less heralded than those of some other WWII heavy-hitters.

Born in Columbus, Ohio, to Erving LeMay, a steel worker and handyman, and his wife Arizona, young Curtis displayed energy and ambition from the start. He worked hard to achieve Eagle Scout rank and dabbled with engines and electronics, built a crystal set and preferred tinkering and hunting to socializing.

LeMay decided that applying for a West Point appointment was too daunting, so instead he joined the Ohio National Guard. Despite his poor academic standing, he demonstrated the persistence that would mark his long career, setting his sights on becoming an aviation cadet.

LeMay became the finest navigator in the Army Air Corps. He helped to develop the famed Norden bombsight, and led a Boeing B-17 heavy bomber group of the Eighth Air Force in England. He later commanded the 4th Bombardment Wing, working to perfect pattern bombing and formation tactics while maximizing the B-17’s defensive firepower and laying the groundwork for long-range missions.

A tough taskmaster, LeMay constantly sought to instill discipline in his crews. Around the briefing rooms and hangars, as well as out on the tarmac, LeMay was known as “Iron Ass.”

Assigned to the Far East in August 1944 after his sterling service in the skies over Europe, General LeMay faced a new enemy, the Japanese, with a new weapon, the Boeing B-29 Superfortress. He led the XX and XXI Bomber commands in China and the Mariana Islands, respectively, and directed punishing fire raids against Tokyo and other Japanese cities.

LeMay also played a major role in selecting Hiroshima and Nagasaki as targets for the first atomic bombs. Tillman, in fact, makes a case that LeMay and Fleet Adm. Chester W. Nimitz were the two commanders most responsible for defeating the Japanese empire.

After WWII ended, LeMay commanded the U.S. Air Force in Europe, organized the Berlin Airlift and, at the apex of his career, headed Strategic Air Command, America’s Cold War spearhead. He later became Air Force chief of staff, and subsequently ran as Governor George Wallace’s vice presidential candidate in 1968.

For his literate, definitive portrait of the intrepid yet largely uncredited airman whose career ranged from 1920s biplane fighters to the North American XB-70 Valkyrie bomber of the early 1960s, Barrett Tillman deserves the highest praise.

Originally published in the July 2007 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.