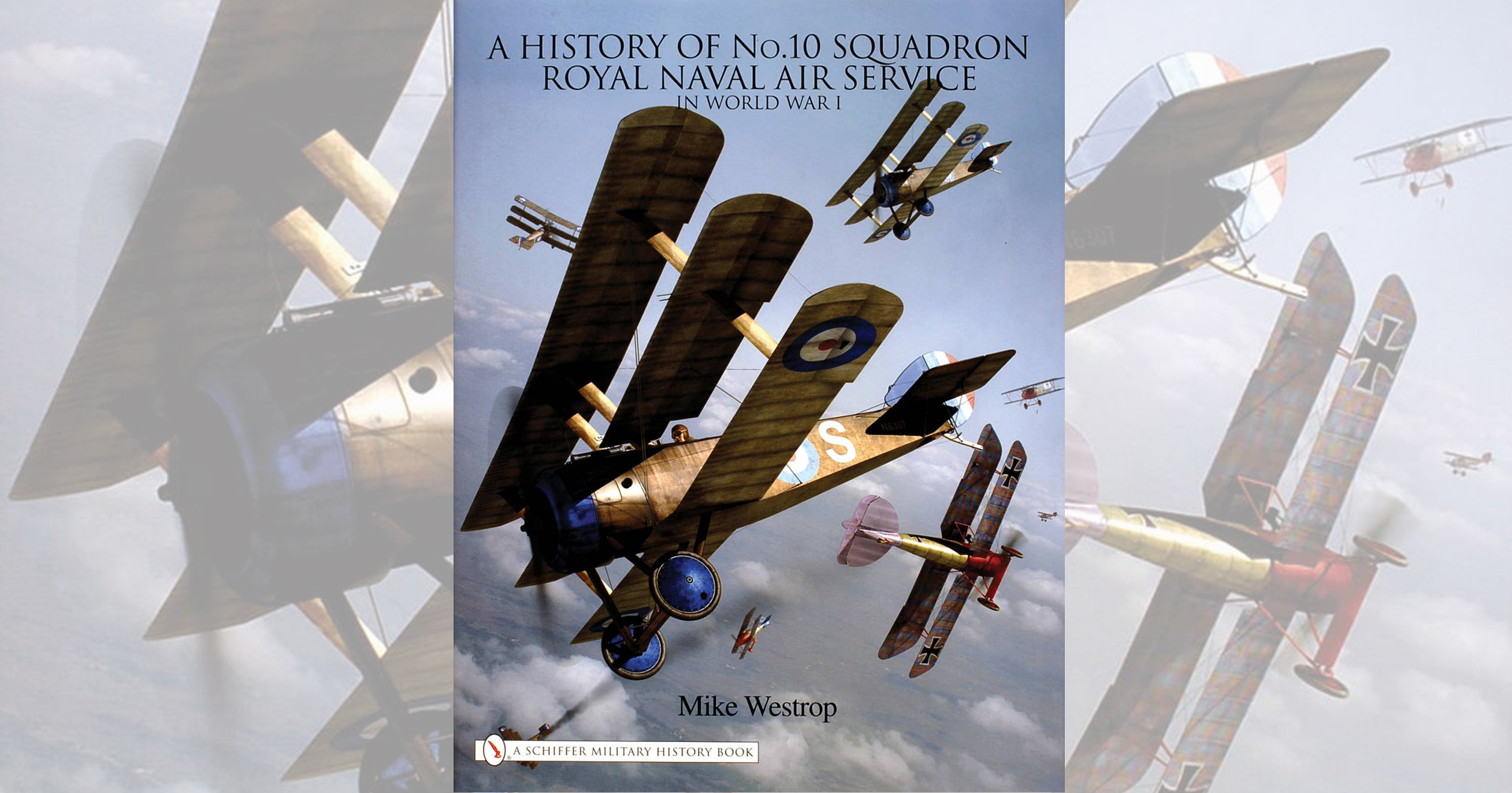

A History of No. 10 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service in World War I by Mike Westrop, Schiffer Publishing, Ltd., Atglen, Pa., 2004, $59.95.

Histories of noteworthy squadrons and groups from World War II have been appearing regularly in recent years, the research behind them yielding increasing amounts of detail and illustrations. Less common have been World War I units, even though several of them achieved fame in their time, such as France’s Stork Group and Lafayette Escadrille, the United States’ 94th “Hat in the Ring” Aero Squadron and Germany’s Jagdgeschwader I, better known to posterity as the Red Baron’s Flying Circus.

Another World War I outfit that gained relatively brief but memorable renown was “Black Flight B of Naval 10,” a flight of five Sopwith Triplanes within No. 10 Squadron, Royal Naval Air Service (RNAS), that for a few months challenged the best fighters and pilots the Germans had over the Western Front. Its Canadian pilots, Raymond Collishaw, W. Melville “Mel” Alexander, Ellis V. Reid, Gerald E. Nash and John E. Sharman, all became aces (Collishaw’s 60 victories place him among the war’s highest-scoring fighter pilots) and derived notoriety from the black noses, wheels and vertical stabilizers by which they identified their flight and the names they gave their triplanes—respectively, Black Maria, Black Prince, Black Roger, Black Sheep and Black Death.

The History of No. 10 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service in World War I, another hefty addition to Schiffer’s ever-expanding library, covers all of Naval 10 from the squadron’s formation in February 1917 up to its redesignation as No. 210 Squadron on April 1, 1918, when the RNAS and the Royal Flying Corps were amalgamated into the Royal Air Force. British author Mike Westrop’s work provides the real exploits that lay behind the legends of Naval 10—and also reveals a darker patch on the squadron’s war record. By the autumn of 1917, Naval 10 had suffered such heavy casualties in the course of unrelenting intense combat over the Flanders sector that its commander, acting on the feedback of some officers, refused to send his pilots on missions. That led to his being relieved of command and the squadron being transferred to a quieter sector in a state of disgrace, though the act of mutinous insurbordination was discretely downplayed, lest it affect other units. Eventually the pilots of Naval 10—and No. 210 Squadron—redeemed their honor, but details of the mutiny are revealed here for the first time.

Schiffer says that The History of No. 10 Squadron Royal Naval Air Service is to be the first in a series of books devoted to Britain’s World War I naval squadrons. If the scholarship, photographs and color illustrations are as lavish as Naval 10’s treatment, then the series should do well—at least among World War I buffs and aviation enthusiasts interested in a multiwinged change of pace from Mustangs and Messerschmitts.

Originally published in the March 2006 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.