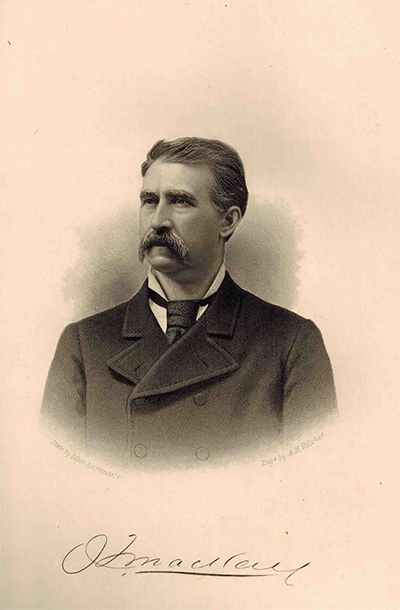

Californian Gregory Crouch has written about mountain climbing in Patagonia (Enduring Patagonia) and World War II aviation in Asia (China’s Wings: War, Intrigue, Romance and Adventure in the Middle Kingdom During the Golden Age of Flight). He sticks closer to home in his latest book, a narrative nonfiction account of industrialist John Mackay and Nevada’s Comstock Lode that’s a lot more than a biography. The Bonanza King: John Mackay and the Battle Over the Greatest Riches in the American West also takes in social history, Irish-American history, the slums of New York, Western mining towns, mine disasters, strikes, bank kings, frontier justice, engineering and myriad other topics. Crouch spoke with Wild West about the book and his interest in the Old West.

After writing about Patagonia and China, what brought you home to the American West?

China’s Wings, my World War II flying story, was a fascinating and all-absorbing project with one crucial problem—every time I wanted to get the flavor of a location, it was on the far side of the Pacific. I spent a month in China early in my research, but I could only afford to go once. Visiting a few other times would have been helpful. So when I needed a new story, I wanted something closer to home. I live in Walnut Creek, about 15 or 20 miles east of San Francisco. Ferreting around in the early history of San Francisco, I kept running into connections to the old Comstock Lode. My mom had taken me to Virginia City in the 1970s, when I was about 10 or 12, and I had really fond memories of that trip. I decided to dig into it.

I read every book I could find about Virginia City and the Comstock Lode. Lots have been written in the last 140 years. Most struck me as falling into one of two camps—either arid and academic and devoid of story, which is boring, or else in love with the whiskey, the gun smoke and the hookers with hearts of gold, which is bullshit. I thought I might be able to hit the sweet spot between those two extremes with a balance of accuracy and story that focused on the struggle to control the Comstock Lode when it was the richest place in the world.

How did you settle on John Mackay?

He’s the only person who could carry the whole epic, from common miner to Bonanza King. He’s the seminal figure in the history of the Comstock Lode.

How did you go about researching the complex history of the Comstock?

I read as much as humanly possible about every aspect of the story. As a researcher, my goal is to so completely saturate my brain with stories, language, photos, illustrations, impressions, sensations and details that four-color visions form in my mind in answer to the question What happened? Once I’m seeing the story in my head—literally seeing it—I try and translate those images into language that tells the story. I have a hard time writing without that.

Technologically, I was greatly helped by the digitization of 19th-century newspaper archives in the last decade or so. That allowed me to process a large quantity of information in a reasonable amount of time—more than others have been able to get through, I think. That made a huge difference. I wouldn’t have been able to do such a thorough job with the old microfiche system. That takes forever. You’d get frustrated and cut things short.

What were the most enjoyable aspects of researching and writing the book?

Of the research? Finding eyewitness accounts in the old newspapers. Far-flung correspondents writing letters back to their parent newspapers were staples of 19th century newspapers. Those correspondents writing from Virginia City helped me see the story of the Comstock Lode in its full glory from the remove of 140 years. I had particular fun with Mary Jane Simpson, “Lady Correspondent” of the San Francisco Chronicle. In the early 1870s Simpson expended many column inches disparaging a strike on the 1,100-foot level of the Crown Point and Belcher mines, railing against it as a “put-up job” to “puff” the stock. She couldn’t have been more wrong. The strike proved to be the apex of an immense ore body. Belcher miners had their revenge when they sent three mules down the shaft to haul ore cars a thousand feet underground. They named one in her honor. Tracing the story of Simpson—the mule—from her first descent underground to her tragic and terrible end several years later filled me with wonder and joy. I’m often astonished by what you can learn if you just keep digging.

Of the writing? Fun? You’re kidding, right? Writing is like digging an endless ditch. In that respect, it’s a lot like mining. I’ve been describing the last push to finish The Bonanza King as “U.S. Army Ranger School for writers.” Six months of 12-hour days, three months of 14- to 18-hour days, three weeks of 20-hour days, then in the last week I pulled three all-nighters. Ranger School was easier. But hey, do hard things, right? They’re the only ones worth doing. I enjoyed Ranger School and I enjoyed writing The Bonanza King. I’d do them both again.

What I really did enjoy about the writing was trying to incorporate the language of the West and of the mining frontier into the story in a manner I hoped would delight modern readers.

‘In my perfect world, a reader of The Bonanza King would open the endnotes on their phone or tablet and scroll along with the reading, finding themselves totally convinced with the accuracy of the story while being thoroughly entertained’

Are you always such a bulldog when it comes to research?

Yes. Narrative nonfiction is my favorite genre to read, by far, and in my opinion a great piece of narrative nonfiction cracks open a world you didn’t know much about with a factually accurate and compelling story. When I’m reading nonfiction, and I hit a wonderful scene, I want to ask the writer, “How do you know that? You weren’t there.” So I flip to the endnotes. In most cases only direct quotations are attributed. About everything else I’m left thinking, Well, maybe. Why should I take your word for it? Quite frankly, I’m not always convinced.

Well, I wasn’t on the old Comstock, either. Why should you take my word for it? You shouldn’t—unless I can convince you that I’m a reliable storyteller. That’s what I aim to accomplish with meticulous endnotes. I want you to see the raw material from which I constructed each important scene. I want you to check my facts. I want you to follow my thought processes and arguments. My hope is that the discipline of meticulous endnotes will convince you I’m a reliable storyteller, as well as provide you with some extra enjoyment. Because endnotes are wonderful.

My editor gave me the option of massively reducing the endnotes and bibliography and putting them at the back of the book or of publishing them whole on my website. For better or for worse, I chose the latter. In my perfect world, a reader of The Bonanza King would open the endnotes on their phone or tablet and scroll along with the reading, finding themselves totally convinced with the accuracy of the story while being thoroughly entertained.

How long did the research take? And the writing?

From start to finish a little bit less than four years.

How does that compare to previous projects?

China’s Wings took eight. But life had me under siege for much of that time, so it’s not a great comparison.

The book often reads like a who’s who of 19th-century America. Who had the biggest influence on Mackay’s life and career, and why?

William Sharon, I think. He was the man Mackay had to dethrone in the battle to control the Comstock Lode. As Mackay’s principal adversary, he almost certainly exerted the most direct influence.

What brought Mackay to the West?

Hope. Mackay came West hoping that hard work and dedication would allow him to transcend the opportunities available to an uneducated Irish immigrant in New York. If Mackay had stayed in New York, more than likely he’d have worked as a ship’s carpenter for the rest of his life, for meager wages. He came west in late 1851, at the tail end of the Gold Rush, by which time the details of California were well known to Eastern audiences. He did not come West expecting easy-made riches. By 1851 that California myth had long since been exploded.

How did Mackay became the Bonanza King, and why he didn’t care much for that title?

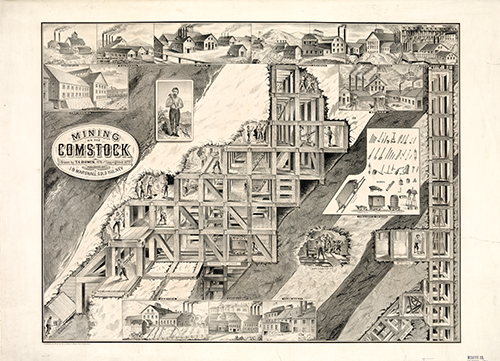

Mackay’s competitive advantage was his legendary capacity for hard work. When Mackay arrived on the Comstock Lode in the spring or early summer of 1859, a few weeks after the lode’s discovery, he didn’t have a nickel to his name. From there he worked his way up from nothing. He took a job working for $4 a day in somebody else’s mine to make the money he needed to survive. He also worked a second shift of hard labor in exchange for “feet,” meaning a share in the mine’s ownership. A mine that claimed a 400-foot slice of the Comstock Lode would divide itself into 400 feet, each “foot” representing a 1/400ths share in the mine’s ownership, just like a share of stock in a modern company. That “sweat equity” represented Mackay’s first accumulations of capital.

Mackay received an education in the art and science of deep, hard rock mining in the same steady manner, by working his way up from the bottom rung. Owners, superintendents and foremen recognized his incredible work ethic and leadership qualities and moved him up, first to timberman, then to job boss and gang leader, underground foreman, foreman and, eventually, superintendent.

Wise speculations in “feet” and his incredible work ethic put him on the road to becoming “Bonanza King.” He had several mining successes—and a few failures—on his way up, always battling the pernicious “Bank Ring” of California capitalists fronted by Sharon, who controlled the best mines. In the 1870s Mackay and his three junior partners—all Irishmen—went “all in” on another mining venture and found a colossal ore body more than 1,000 feet below the streets of Virginia City. Miners came to call it the “Big Bonanza,” and it proved the most valuable concentrated body of gold and silver ore ever discovered. With it Mackay eclipsed the Bank Ring. And since Mackay controlled the Big Bonanza, that made him the “Bonanza King.”

Mackay loathed the nickname. He was a modest, self-effacing. “It doesn’t make anything of me but a millionaire with a swelled head,” he’d say.

What was Mackay like as a family man?

By all accounts John Mackay was devoted to his wife and two sons. Mackay’s wife, Louise, had been married before, to a promising young doctor who developed a powerful thirst for “the territorial destructive,” whiskey, an addiction to one of the only useful medicines in his doctor’s bag, opium, and almost certainly abused Louise and their daughter, Eva. The doctor died of tetanus, probably from injecting himself with an infected needle.

A few years after he married Louise, Mackay formally adopted Eva, which reflected his affections.

‘Of the magnates, Mackay was the richest of them all, by a large margin, and much more widely admired’

How does Mackay compare to lode namesake Henry Comstock?

Of the magnates, Mackay was the richest of them all, by a large margin, and much more widely admired. Henry Comstock is the foil to Mackay’s success. When Mackay had nothing in the early days, Comstock was rich. Comstock owned several important slices of the lode that came to bear his name. Comstock sold out in the first season, squandered his money in ill-fated speculations and was soon forced to return to prospecting. He spent most of the next 10 years searching for “another Comstock” in eastern Oregon, Nevada and the Idaho, Montana and Dakota territories. He never found it. By 1870 $100 million had been “raised” from the lode that bore his name. The man himself was destitute. Outside of Bozeman, Montana Territory, in September 1870, Comstock clenched the barrel of a revolver between his teeth and pulled the trigger. In the 10 years after his death another $200 million came out of the Comstock mines. Mackay’s share of that wealth made him one of the richest men in the world.

Incidentally, Henry Comstock is buried in Bozeman’s Sunset Hills Cemetery, just a few yards from the grave of Nelson Story, the man who drove the first herd of cattle from Texas to Montana—the epic cattle drive that inspired Larry McMurtry’s classic Lonesome Dove. That two such significant Western figures ended up buried so close to each other boggles my mind.

No mining history is complete without a cave-in or other disaster. Talk about the disastrous mine fire of 1869 and how that affected the Comstock and Mackay.

Mining today is a dangerous profession. Mining in the 19th century was staggeringly dangerous. When I first started the research, I thought “caves” or collapses would be a miner’s greatest fear. Not even close. A cave only kills those men directly underneath, and signs of impending collapse usually give miners opportunity to flee. The disaster miners fear before all others is fire. Comstockers worked by the light of open candle and lantern flames in mines shored by hundreds of thousands of feet of dried, compressed timber. They lived in fear of fire, for an underground fire sucks the oxygen from the atmosphere of an entire mine, fills it with smoke and stifling gas, and inflicts a horrible, suffocating death on men far from the conflagration. Every person stuck underground dies an agonizing death.

On Wednesday, April 7, 1869, a miner committed one of mining’s cardinal sins on the 800-foot level of the Yellow Jacket mine—he left a candle burning unattended. The tiny flame spread to the mine timbers. As the fire spread, and the mine filled with smoke, the dozens of men underground fought for space on the “cages”—the elevators that lowered and raised men, supplies and ore from the mines. About half escaped. The rest did not. The fire killed 37 men in the Crown Point, Kentuck and Yellow Jacket mines, made 10 widows and killed the fathers of more than 20 children. The sources for that episode are good. It was the first scene I wrote.

Mackay had made his first big “raise” out of the Kentuck mine in 1866 and 1867, and although he’d sold his interest in the mine more than a year before the fire, he’d worked alongside many of the men killed underground.

What do you want readers to take away from The Bonanza King?

The flavor of life in Virginia City during the Comstock heyday, the sense of Mackay as one of the great forgotten men in U.S. history, and an understanding of what an important role the Comstock Lode played in 19th century America—it was the Silicon Valley of the age.

What’s the one question you want to be asked about the book?

This isn’t really an answer, but ever since I became interested in John Mackay and the Comstock Lode, whenever I’m confronted by something that seems difficult, I ask myself, “What would John Mackay do?”

And the answer is obvious — he’d push up his sleeves and get to work.

What’s next for you?

I’m exploring options. Know any good stories? I’ve hit on a few good ones, but haven’t yet carved anything in stone. But I enjoyed my time on the Comstock Lode. I’d like to stay in the Old West. WW