AS HE CONTEMPLATED THE SCENE AT BRISTOE STATION, VIRGINIA, on the evening of August 27, 1862, Major General John Pope of the Union army was in a surprisingly upbeat mood. Although three crack Confederate divisions under Major General Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson had cut his railroad supply line to Washington, D.C., and forced him to pull back from the Rappahannock River, Pope remained stubbornly optimistic. “Jackson, [Richard S.] Ewell, and A. P. Hill are between Gainesville and Manassas Junction,” the 40-year-old commander of the Army of Virginia informed his subordinates. “If you will march promptly and rapidly, at the earliest dawn of day, upon Manassas Junction, we shall bag the whole crowd.”

Such unbridled optimism was typical of Pope, who made up in self-confidence what he lacked in tact. A little over a month earlier, on taking command of the Army of Virginia, Pope had bombastically promised to deliver the victories President Abraham Lincoln had long been hoping for.

Born in Kentucky and raised in Illinois, Pope was the son of Nathaniel Pope, an influential federal judge and longtime friend of Lincoln. After graduating from the U.S. Military Academy in 1842, Pope worked as a topographical engineer, surveying routes in the West for the much-anticipated transcontinental railroad, and serving in the Mexican-American War under Brigadier General Zachary Taylor. Commissioned a brigadier general in the United States Volunteers at the outset of the Civil War, Pope first exercised command in Missouri under Major General John C. Frémont (the first in a series of officers with whom he would clash during the war). His capture of Confederate-held Island No. 10 on the Mississippi River in April 1862 and his role in the capture of Corinth, Mississippi, the next month so impressed Lincoln that he brought Pope east in late June 1862 and put him in command of the newly formed Army of Virginia.

The new army—and Pope’s appointment to lead it—grew out of Lincoln’s manifest unhappiness with Major General George B. McClellan’s conduct of operations against Richmond, Virginia, in the just-concluded Peninsula Campaign. Recalling most of the soldiers in McClellan’s Army of the Potomac to northern Virginia, the president aimed to use them to beef up Pope’s forces and help him conduct offensive operations that would produce the sort of military victory McClellan had failed to deliver.

Lincoln’s decision left Pope brimming with bravado. “Let us understand each other,” he thundered in a proclamation issued to his army in July.

I have come to you from the West, where we have always seen the backs of our enemies; from an army whose business it has been to seek the adversary and to beat him when he was found; whose policy has been attack and not defense.…I hear constantly of “taking strong positions and holding them,” of “lines of retreat,” and of “bases of supplies.” Let us discard such ideas. The strongest position a soldier should desire to occupy is one from which he can most easily advance against the enemy. Let us look before us, and not behind. Success and glory are in the advance, disaster and shame lurk in the rear.

While Pope wasn’t entirely wrong about the overall direction of the Union effort in the East, his attitude did not endear him to his new command. Brigadier General Alpheus S. Williams would privately ridicule Pope’s “pompous orders” and “high sounding manifestoes,” which, he said, “greatly disgusted his army from the first.” In a letter to his daughter in September, Williams declared:

“When a general boasts that he will look only on the backs of his enemies, that he takes no care for lines of retreat or bases of supplies; when, in short, from a snug hotel in Washington he issues after-dinner orders to gratify public taste and his own self-esteem, anyone may confidently look for results such as have followed the bungling management of his last campaign. More insolence, superciliousness, ignorance, and pretentiousness were never combined in one man.”

Samuel D. Sturgis, one of Williams’s fellow generals, was pithier in expressing his disgust for Pope, saying: “I don’t care for John Pope one pinch of owl dung.”

WHILE POPE POSTURED, ROBERT E. LEE ACTED. Having frustrated McClellan’s advance on Richmond, the commander of the Army of Northern Virginia turned to the new Union threat. On July 13, a day after Pope’s forces occupied Culpeper Court House, bringing them about 30 miles north of the vital railroad junction at Gordonsville, Lee sent Stonewall Jackson with two divisions of infantry and an artillery battery—10,000 men in all—north to protect the junction. “I want Pope to be suppressed,” he told Jackson. The two Virginians were incensed at Pope’s treatment of southern civilians. Pope had ordered his men to live off the land wherever they were and to take whatever they wanted from families living there. He had also demanded that all male noncombatants swear an oath of allegiance to the federal government. Those who refused were to be expelled from the area, and anyone caught returning would be hanged as a spy. Furthermore, anyone daring to contact members of the Confederate army—even parents writing to their sons—would likewise be subject to execution. Pope, Lee said with rare vehemence, was nothing more than a “miscreant.”

The opposing armies clashed first on August 9 at Cedar Mountain, eight miles south of Culpeper. There, Jackson won a hard-fought victory, inflicting nearly twice as many Union casualties (2,400) as his Confederates suffered (1,350). At the same time, Lee learned from intelligence sources that Major General Ambrose Burnside’s IX Corps had arrived from North Carolina to reinforce Pope in Northern Virginia, while McClellan’s army was leaving the Peninsula. Lee sent Major General James Longstreet, whom he called “my old war horse,” and several divisions north to join Jackson behind the Rapidan River. If Lee could strike Pope before he could link up with McClellan and Burnside, the Southerners might claim a significant victory.

Lee arrived at Gordonsville on August 15 to take control. A week later, he sent Major General J. E. B. Stuart, his vaunted cavalry commander, raiding around Pope’s right flank and rear; Stuart struck the general’s headquarters at Catlett’s Station on August 22. The effort to burn the railroad bridge over Cedar Run, an important link to Pope’s supply line, was frustrated when heavy rain flooded the roads. Despite this bad luck, Stuart managed to carry away hundreds of Union prisoners as well as Pope’s personal baggage, dress coat, and dispatch book. Captured documents revealed that reinforcements from the Army of the Potomac were about to arrive, while probes across the river showed that Pope’s defensive line along the Rappahannock River was strong. Faced with an unacceptable stalemate against a burgeoning enemy army, Lee decided to have Jackson take his three divisions around Pope’s right flank to cut the main Union supply line at Manassas Junction, where the Orange & Alexandria Railroad connected with the Manassas Gap Railroad.

Jackson’s seasoned “foot cavalry” swiftly marched north to Salem, covering 25 miles in a day. The next morning the Confederates advanced through Thoroughfare Gap, west of Haymarket, where the Manassas Gap Railroad cut through the Bull Run Mountains six miles west of Gainesville. The gap, an officer reported, was “a rough pass…at some points not more than a hundred yards wide.” Jackson and his men reached Bristoe Station around sunset—another 25 miles of marching. After derailing a Union supply train, Jackson sent Brigadier General Isaac R. Trimble with two infantry regiments and cavalry to secure Manassas Junction.

When the Confederates reached the depot on the morning of August 27, they found an embarrassment of riches, from lobster to oranges (“all the delicacies,” one of them would later recall). The hungry soldiers gorged themselves on the booty, stuffing into their backpacks, hats, and pockets whatever they could not devour on the scene. Jackson, a teetotaler, had wisely ordered his officers to break open and dump hundreds of barrels of whiskey, wine, and brandy to prevent drunkenness in the ranks. On the night of August 27, Jackson’s men began moving toward Groveton to take up a position west of where the Warrenton Turnpike crossed Bull Run. There, Jackson would wait for Lee and Longstreet to join him with the rest of the army.

POPE, SIZING UP THE SITUATION THAT EVENING, CONCLUDED THAT THE REBELS HAD UNWITTINGLY handed him a golden opportunity. Major General Irvin McDowell’s wing of the army, which included his own corps and the corps commanded by Major General Franz Sigel, was marching east along the Warrenton Turnpike and would soon reach Gainesville. Once there, McDowell’s men would be able to block any attempt by Jackson to escape back through Thoroughfare Gap—even assuming that he wanted to do so. McDowell could then advance on Manassas Junction while the rest of Pope’s command moved on Jackson from the south. Jackson and his men would be trapped.

As Jackson’s men feasted at Manassas Junction on August 27, McDowell dutifully marched his command east along the Warrenton Turnpike. The three divisions of Sigel’s corps took the lead, followed by a division of Pennsylvania Reserves commanded by Brigadier General John F. Reynolds. Next was Brigadier General Rufus King’s division, with Brigadier General James B. Ricketts’s division bringing up the rear. Unlike Pope, McDowell was deeply concerned that the enemy might use Thoroughfare Gap as something other than an escape route. What if the rest of Lee’s army was aiming to head through the gap to reunite with Jackson’s forces? In that case, McDowell worried, things could turn bad for the Federals very quickly.

McDowell’s unease was underscored by the reports he had received from Brigadier General John Buford, whose brigade of cavalry had spent much of the day on the other side of the Bull Run Mountains. There, they had engaged elements of what was unmistakably Longstreet’s wing of the Confederate army, putting up such stiff resistance that at one point Longstreet felt compelled to deploy his entire command between Salem and White Plains.

Buford knew that he could not prevent Longstreet’s 25,000-plus men from reaching Thoroughfare Gap, and he made sure that McDowell knew it too. Around 9 p.m., with Buford’s reports in hand, McDowell made his way to Sigel’s camp at Buckland Mills, where the turnpike crossed Broad Run three miles from Gainesville. Entering the small house where Sigel had his headquarters, McDowell wasted no time getting to the point. “General Sigel,” he asked, “what would you recommend?” Sigel informed McDowell that his scouts had reported that Longstreet had been at Salem, nine miles west of Thoroughfare Gap, earlier that day and was expected to reach Gainesville by 9 a.m. the next morning. This matched the information McDowell had received from Buford and reinforced his growing concern that Longstreet would try to come through Thoroughfare Gap in the morning.

Sigel speculated that Jackson and Longstreet intended to link up at Gainesville. “If we start early in the morning,” he told McDowell, “we can reach there before Longstreet and we can whip Jackson.” As McDowell wrestled with his options, an exhausted Sigel lay down on a sofa. “I told General McDowell that as soon as he had come to an understanding with himself,” Sigel later reported, “he should please notify me.” Then he fell asleep.

At about 11:30 p.m., after studying a map for more than an hour, McDowell finally reached a decision. Something, he realized, had to be done about Longstreet. McDowell drew up orders directing Sigel’s corps and Reynolds’s division to march to Haymarket, four miles east of Thoroughfare Gap, and confront Longstreet. Meanwhile, King and Ricketts would march to Gainesville, where they would be ready either to go to Sigel’s aid or to move on to Manassas Junction.

McDowell would not have the chance to reap the potential rewards of his well-considered orders. Shortly after he issued them, Pope’s own order to move his command toward Manassas Junction on the 28th (“Be expeditious, and the day is our own”) arrived from Bristoe Station. McDowell decided to drop his plan. Instead, Sigel and Reynolds, as well as the rest of his command, would move toward Manassas Junction in accordance with Pope’s order.

Unlike McDowell, neither Longstreet nor Lee felt undue anxiety over the situation. They had left the Rappahannock River the previous afternoon with three divisions of infantry and were at Orleans before the end of the day. The next day, a courier reached Lee with a report from Jackson saying that matters were well in hand, that the route through Thoroughfare Gap was clear, and that nothing stood in the way of reuniting the Army of Northern Virginia. Lee and Longstreet marched their men to Salem on a now hot and dusty August 27, reaching it in the late afternoon. Elements of the Union cavalry, undoubtedly belonging to Buford’s command, made a sudden appearance at Lee’s bivouac, but an aggressive response from the general’s men sent the Federal horsemen into retreat. That evening Longstreet’s men reached White Plains, and Confederate scouts reported that Thoroughfare Gap was still clear.

CONTRARY TO POPE’S EXPECTATIONS, JACKSON WAS IN NO DANGER of being “bagged” on August 28. While Longstreet’s men camped at White Plains, Jackson ordered his men to move to Groveton on the Warrenton Turnpike. This placed them close enough to Thoroughfare Gap to make linking up with Longstreet eminently feasible. The men filed behind a low ridge north of the turnpike and then lay down behind the ridge to rest. They were, a Confederate later remembered, “packed in there like herring in a barrel.”

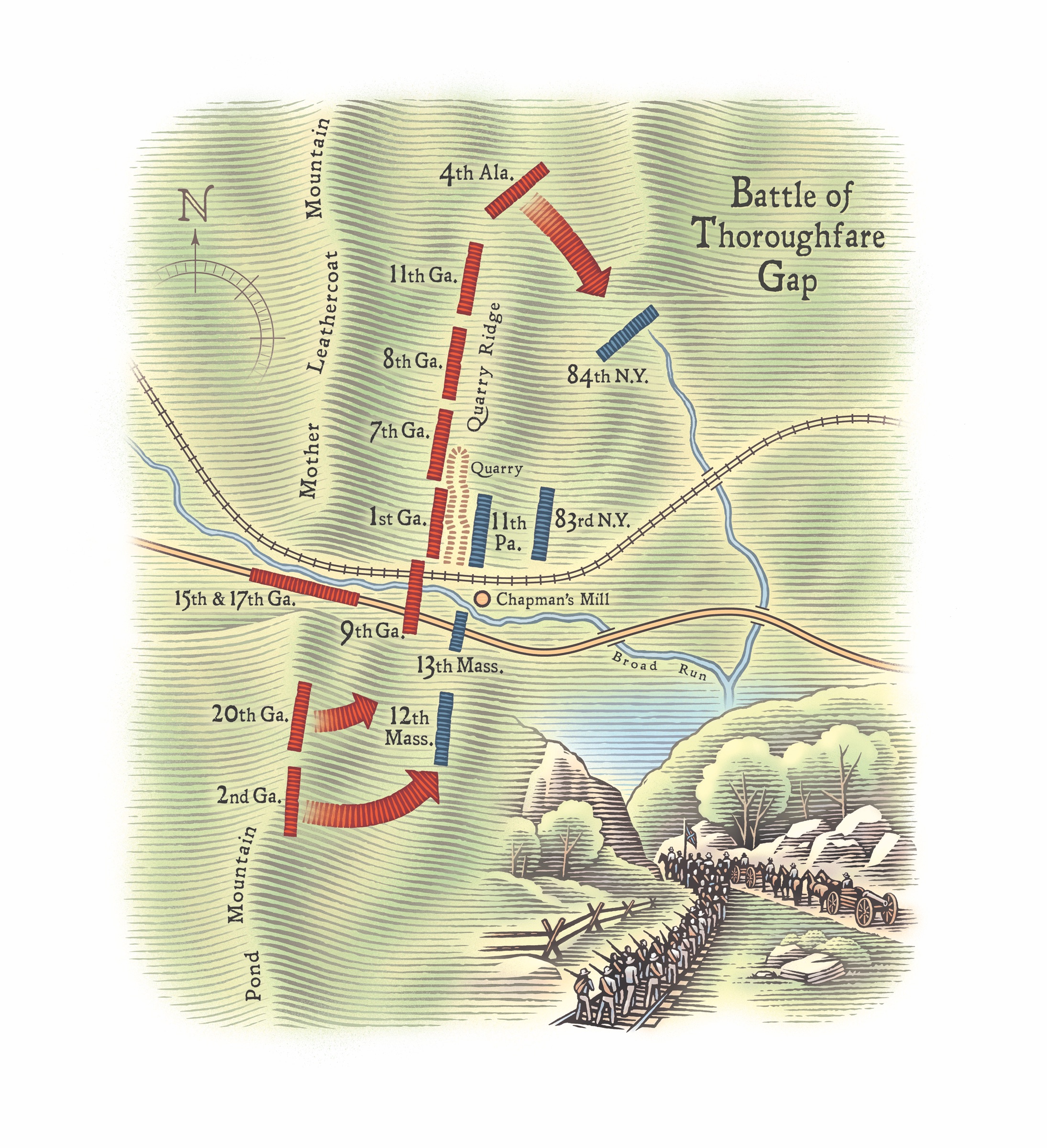

By late morning on August 28, Longstreet’s lead elements were poised to enter Thoroughfare Gap. After advising Jackson that the rest of the army would join him the following day and briefly contemplating the idea of calling an end to the march, Lee directed Longstreet to go ahead and push a brigade into the gap. Around 3 p.m., Colonel George T. Anderson’s brigade from Brigadier General David Rumph Jones’s division entered the gap. “Tige” Anderson had led his five regiments of Georgians throughout the Peninsula Campaign earlier that year. As they marched toward the western entrance to Thoroughfare Gap, the Confederates passed Galemont, a large estate belonging to lawyer Thomas B. Robertson. On the property was the Broad Run station of the Manassas Gap Railroad, which passed through Thoroughfare Gap en route to Manassas Junction. As they passed Galemont, Anderson’s men could look left and see the rugged slopes of Mother Leathercoat, a small mountain that, according to local legend, George Washington himself had named during his days as a surveyor.

Mother Leathercoat marked the southern end of the section of the Bull Run Mountains that ran north about six miles to Hopewell Gap. Looking right, Anderson’s men could see Pond Mountain, which ran south from Thoroughfare Gap for about four miles to a point where the Warrenton Turnpike cut through the mountains near New Baltimore. As the Confederates passed the narrowest point in the gap, they were about 13 miles northwest of Manassas Junction and could see the high ground of Quarry Ridge north of Broad Run about 500 yards in front of them.

Despite his well-founded concerns about what might be coming his way from Thoroughfare Gap, McDowell aimed to do his best to meet Pope’s demand for an aggressive advance on Manassas Junction on August 28, while also wisely exercising some discretion in managing his command. Sigel, Reynolds, and King, he decided, would march on Manassas Junction. Ricketts’s division, however, after reaching Gainesville, would only move on Manassas Junction, McDowell cautioned, “if on arriving there no indication shall appear of the approach of the enemy from Thoroughfare Gap.” McDowell’s orders further directed that Ricketts “be constantly on the lookout for an attack from the direction of Thoroughfare Gap, and in case one is threatened, he will form his division to the left and march to resist it.”

In addition, McDowell decided to send Colonel Sir Percy Wyndham’s 1st New Jersey Cavalry to Thoroughfare Gap to keep a watch out for Longstreet’s command. Wyndham and his men went to work the morning of August 28 cutting down trees to obstruct the road between Haymarket and Thoroughfare Gap.

Shortly after 9:30 a.m., elements from Wyndham’s command patrolling west of the gap made contact with Longstreet’s command, and Wyndham promptly sent word back to his superiors. McDowell, who accompanied King’s division that morning, was not surprised at the news. He immediately directed Captain Craig Wadsworth of his staff to find Ricketts. Wadsworth located Ricketts and his four brigades on the turnpike between Buckland Mills and Gainesville and gave him McDowell’s order to take his command to Thoroughfare Gap to support Wyndham.

Ricketts, a 45-year-old West Point graduate, had played a conspicuous role as the commander of an artillery battery at the Battle of First Manassas, where because of some dubious tactical decisions by one Irvin McDowell, he had been wounded and captured. Although Ricketts had seen action at the Battle of Cedar Mountain after his exchange and return to duty, the fight for Thoroughfare Gap would be his first significant test as a division commander.

RICKETTS DIDN’T SEEM DAUNTED BY THE PROSPECT. Arriving at Haymarket, he promptly directed the 5,000 men in his command to discard their knapsacks and sent skirmishers toward Thoroughfare Gap. Soon Ricketts’s men ran into Wyndham’s men falling back from the gap, which they reported was already in possession of the enemy. Ricketts responded by directing the commander of his lead brigade, Colonel John W. Stiles, to move toward the gap with all possible speed. Brigadier General Abram Duryée’s and Colonel Joseph Thoburn’s brigades would follow, with Brigadier General Zealous Tower’s brigade held in reserve.

Stiles had assumed command of his brigade only three days earlier, but like Ricketts he showed commendable alacrity in moving his men toward the gap. But Stiles’s progress, Ricketts later complained, was “entirely obstructed” by the fallen timber that Wyndham’s men had placed across the road earlier in the day. Finally, Stiles’s lead regiment, Colonel Richard Coulter’s 11th Pennsylvania, managed to reach a point less than a mile from the gap. There, as a company from the 12th Massachusetts pushed forward as skirmishers, Coulter’s men deployed into line before resuming their advance. Not long after doing so, the Federals made contact with Colonel Benjamin Beck’s 9th Georgia, which Anderson had sent forward to reconnoiter. Beck responded by deploying into line himself before finding the Federals in greater numbers than he could handle and falling back toward Chapman’s Mill. The five-story sandstone gristmill on the banks of Broad Run below Quarry Ridge had helped to feed American soldiers in every war dating back to the French and Indian War, including the Confederate army that defended northern Virginia the previous winter.

As the Georgians fell back, Stiles moved up the rest of his brigade and pushed forward with Colonel Fletcher Webster’s 12th Massachusetts on the left, Colonel Samuel H. Leonard’s 13th Massachusetts in the center, and Coulter’s men on the right, with the 84th New York supporting them. Backed by six pieces of artillery, Stiles’s men advanced until they reached the vicinity of Chapman’s Mill. In their front they found Anderson’s command, with the 9th Georgia in position to the right of the mill and the other four Georgia regiments struggling to move up the rugged slopes of Mother Leathercoat to Beck’s left. The hill was so steep that the men had to grab hold of bushes to haul themselves up.

Fire from Lieutenant Charles Brockway’s section of Battery F, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, forced the men in Beck’s command who had sought shelter inside Chapman’s Mill to abandon it. At this point, some of Leonard’s men entered the mill and worked their way up to the second floor to get better shots at the enemy. The bulk of the two Massachusetts regiments in Stiles’s command crossed to the south side of Broad Run. There, elements from the 12th Massachusetts skirmished with the Confederates, but otherwise the regiment was not heavily engaged. Meanwhile, to the north, the men of the 1st Georgia extended the Confederate line up Quarry Ridge and soon found themselves in a tough fight with Coulter’s Pennsylvanians, who had pushed up the ridge and established a strong line on the other side of a 15-foot-deep quarry trench. Neither side seemed able to gain an advantage. “I was near enough to the federal line,” W. H. Andrews of the Georgia Regulars later wrote, “to have touched bayonets with the man in front of me.”

BY NOW RICKETTS REALIZED THAT WHATEVER HOPES HE HAD OF DRIVING the Confederates back through Thoroughfare Gap were decidedly unrealistic. As all but one of the other divisions under McDowell’s command had moved in the direction of Manassas Junction (with no shortage of fumbling and thrashing about as the high command tried to determine Jackson’s whereabouts), there was no prospect of receiving assistance. The other division, King’s, was also out of reach, having marched east along the turnpike until it found itself hotly engaged with Jackson’s command near Groveton. The fighting that began there on the afternoon of August 28 could be heard at Thoroughfare Gap. “I felt that the sound of each gun was a call for help,” a Confederate later recalled.

Lee, also hearing the sound of fighting, rode to a hill west of the gap to monitor the situation. After issuing the necessary orders to get elements from his command moving up forward on either side of the gap, he calmly accepted an invitation to dinner with Thomas Robertson at his Galemont estate and left the battle in the hands of his subordinates.

As Stiles’s and Anderson’s men exchanged fire on Quarry Ridge and east of the gap near Chapman’s Mill, skirmishers from Leonard’s regiment began climbing the slopes of Pond Mountain. As they approached the summit, they ran into the 2nd and 20th Georgia from Colonel Henry L. Benning’s brigade, which had been ordered to ascend the mountain and turn the Federal left. Reaching the summit first, Benning’s men quickly sent the Massachusetts men back down the mountain. Confederate Colonel John Coussons, who served as a scout that day, later memorialized the Georgians’ feat. “Never, perhaps, in all the tide of time was an unnoted stroke of war more fruitful of results than was that headlong scramble over the mountain,” Coussons wrote in 1906. “It saved Stonewall Jackson from destruction; it opened the way for Longstreet; it reunited Lee’s army; it made the Second Battle of Manassas a possibility and an actuality; and thus crowned the campaign of 1862 with the best balanced battle and the most brilliant victory ever won on American soil.”

To deal with the situation on the other end of the line, Confederate brigadier general Evander M. Law’s brigade received similar orders to ascend Mother Leathercoat. Unfortunately for Law, the local guide assigned to him got lost. Law and his men finally managed to reach the crest after an exhausting climb, only to find themselves facing what Law later described as “a natural wall of rock which seemed impassable.” Law’s men managed to locate a narrow crevice that, while only able to accommodate a single man at a time, allowed enough men to squeeze through and help Law resume the advance against the Union right. The delay gave Ricketts time to bring up Colonel Samuel Bowman’s 84th Pennsylvania from Thoburn’s brigade and check the threat to his right. Bowman’s arrival stabilized the situation, and the bitter struggle on the ridge ended that evening with neither Anderson nor Law able to achieve much against the Federal defenders.

By then, however, Ricketts had decided that he had accomplished all he could. “Considering our position untenable and all efforts to take the pass unavailing,” as he would later write, Ricketts ordered his men to retreat. At Haymarket he located Buford’s and Brigadier General George Bayard’s cavalry brigades, which covered his withdrawal to Gainesville. That evening, understandably worried about his command’s isolation, Ricketts decided to pull back to Bristoe Station, thus clearing the way for Lee to reunite Longstreet’s and Jackson’s commands on August 29. His stout but futile stand had cost Ricketts about 90 casualties, the majority coming from Coulter’s regiment.

IN THE END, IT WAS ALL FOR NAUGHT. TO ANYONE WHO COULD LOOK AT A MAP of northern Virginia, the military importance of Thoroughfare Gap was hard to miss. Yet from the time he learned of Jackson’s raid on Manassas Junction, Pope focused so much on his effort to “bag” Jackson that he rendered himself oblivious to the possibility that Longstreet’s command might use the gap to reach Jackson and the battlefield. It was one of the most remarkable failures of generalship in the entire war. On the night of August 28, Pope was still telling his staff, “The game is in our own hands, and I do not see how it is possible for Jackson to escape without very heavy loss, if at all.” He issued new orders to his corps commanders, laying the groundwork for the series of assaults they would launch on Jackson’s position the next morning.

The subsequent two-day Battle of Second Manassas, fought on much the same ground as the first battle 13 months earlier, ended in another humiliating defeat for the Union. A critical turning point in the campaign came, as McDowell and other Pope subordinates had anticipated, when Longstreet brought his wing of the Confederate army through Thoroughfare Gap to a position from where he could launch a massive counterattack on August 30 that forced Pope’s army to leave the field in defeat. After losing nearly 14,000 men, including more than 1,700 dead, Pope retreated to Washington. Contradicting his earlier vainglorious pronouncement about always seeing the back of the enemy, it was now Pope’s own back that was being glimpsed—however fleetingly—as he dashed into the safety of the capital. His father’s ever-loyal friend President Lincoln said, “Pope did well, but there was an army prejudice against him.”

After Pope’s failure to secure Thoroughfare Gap, that prejudice only increased. Lincoln hastily transferred him to Minnesota, where he had somewhat better luck fighting outnumbered and outgunned Sioux warriors in the Dakota War of 1862. Then again, there were no mountain gaps to defend in Minnesota—and no Stonewall Jackson or Robert E. Lee sitting in council with the Dakota chiefs. MHQ

Ethan S. Rafuse is professor of military history at the U.S. Army Command and General Staff College. The author of Manassas: A Battlefield Guide (University of Nebraska Press, 2014), he is the 2018–2019 Charles Boal Ewing Chair in Military History at the U.S. Military Academy at West Point.

[hr]

This article appears in the Summer 2019 issue (Vol. 31, No. 4) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Asleep at the Gap

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!