Their Maryland: The Army of Northern Virginia From the Potomac Crossing to Sharpsburg in September 1862, a new book by Alex Rossino, published by Savas Beatie, explores in detail General Robert E. Lee’s 1862 Maryland Campaign. The following is Appendix A, which examines paintings created by artists on both sides depicting the Confederate army’s trek to Sharpsburg, Md., that September. Reprinted with permission of Savas Beatie.

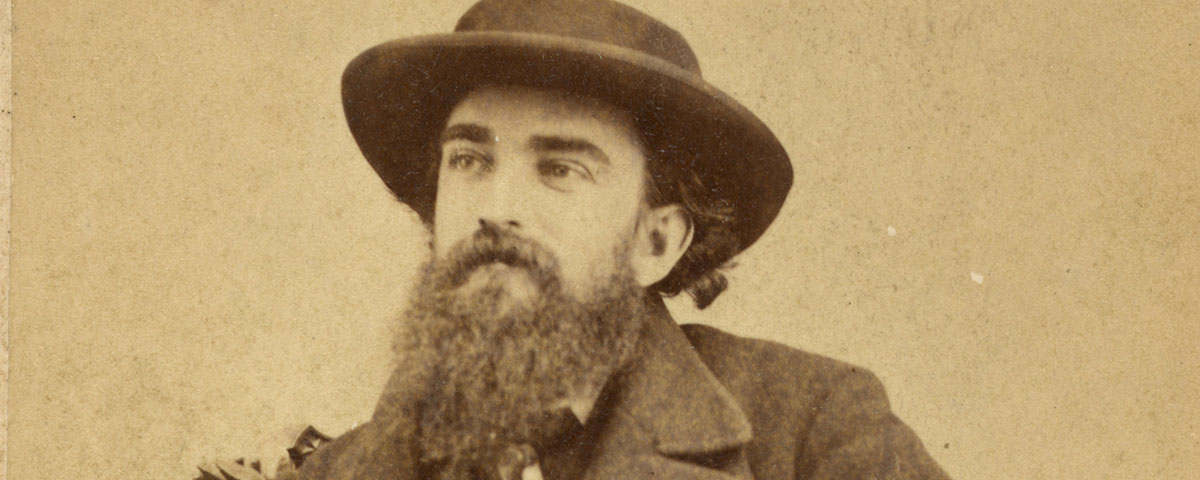

Alfred Waud’s Nearly Forgotten Sketch

Alfred R. Waud created his sketch of the Army of Northern Virginia’s Potomac River crossing first. An intrepid illustrator born in London, England on October 2, 1828, Waud found employment in early 1862 as a sketch artist with Harper’s Weekly. He was assigned to cover Federal military operations and traveled through Virginia drawing events until the calamitous defeat of John Pope’s army at the Battle of Second Manassas in late August of that year. Caught up in the chaos surrounding the Federal retreat, Waud quickly found himself trapped behind Confederate lines. However, instead of attempting to return to Washington on the south side of the Potomac River, he decided to trail the Confederate army north through Leesburg, Virginia.

According to a September 7 report sent by Alfred Pleasonton, the Army of the Potomac’s cavalry commander, to the headquarters of Maj. Gen. George McClellan, Waud traveled through Leesburg before crossing into Maryland at White’s Ford with James Longstreet’s command on September 6. Troopers with the 1st Virginia Cavalry screening the right (eastern) flank of Lee’s army apprehended Waud soon thereafter, resulting in a fanciful drawing of them that a notation in the artist’s diary says he completed on September 7. Waud then produced his drawing of Lee’s army crossing the Potomac on September 8, although he later captioned the image “Previous to Antietam. Rebels crossing the Potomac. Union scouts in foreground.”

Waud sketched his original in pencil, but some unidentified individual, perhaps another artist at Harper’s Weekly, later rendered it as a black-and-white watercolor painting. Oddly enough, only Waud’s sketch of the 1st Virginia Cavalry appeared in Harper’s on September 27, 1862. His river sketch seems to have been forgotten and might have been lost forvever had the estate of banking mogul John Pierpont Morgan Sr., not donated a collection of Civil War era drawings to the Library of Congress that included Waud’s image.

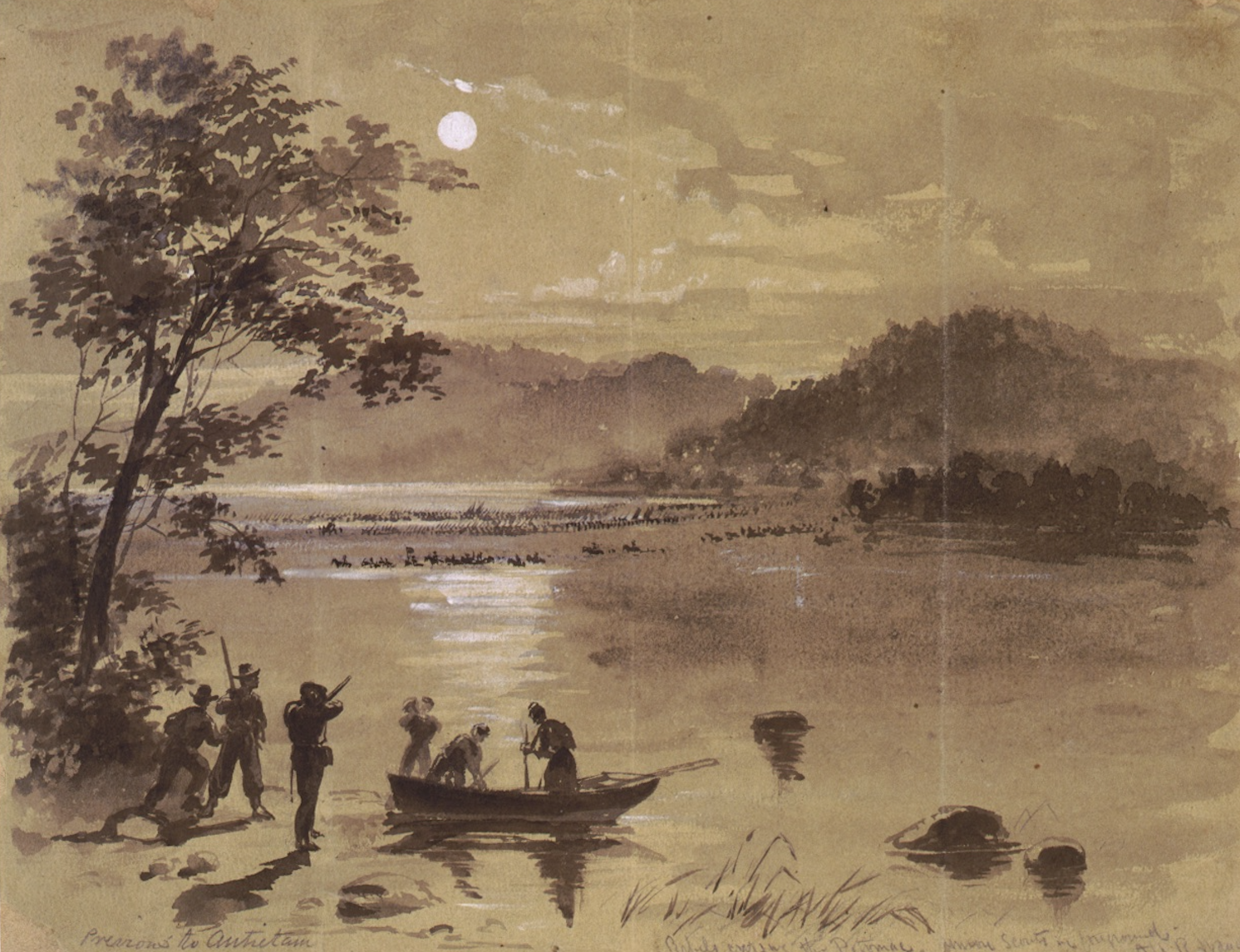

Even though Waud crossed the Potomac with Longstreet’s men, there are aspects of his image which make it clear he chose not to depict that particular event. The first of these is the mountainous terrain in the background. There are no hills near White’s Ford that approach the height shown by Waud. The same is true of the crossing points used by J.E.B. Stuart’s cavalry farther south of the ford, specifically Conrad’s Ferry (known after the war as White’s Ferry) and Edwards’ Ferry. The setting for the crossing is therefore a work of imagination, with Waud depicting the Confederate columns in a romanticized landscape of wooded hills sloping down dramatically to the river. He may have been attempting to depict the Catoctin Mountain range, but there is no evidence to confirm that.

Whatever the case might have been, Waud clearly relied on details he learned from Rebel horsemen in Maryland to help compose his image. For example, the bright moon hanging in the upper-center of the drawing is accurate for the crossing made by a portion of J.E.B. Stuart’s men. Wade Hampton’s cavalry brigade forded the Potomac on the “clear moonlit night” of September 5, a fact Waud could only have known if he learned it from the Rebels in Leesburg or those he met on the Maryland side of the river. In addition, Conrad’s Ferry is located close to the Ball’s Bluff battlefield, something Rebel troopers likely mentioned to orient Waud, which could explain why he incorporated the impression of wooded hills to the south of the Confederate column in his image. Taken together, the presence of these hills and the moonlit night suggest that Waud tried to capture the sight of Confederate cavalry traversing the river at Conrad’s Ferry. He did not witness the crossing with his own eyes, however, making the sketch more an informed artistic portrayal than a reliable depiction of the event itself.

Nast’s Propaganda Drawing

Thomas Nast’s drawing appeared in the September 27, 1862, issue of Harper’s Weekly and, like Waud’s image, it is a combination of fact and fiction. The German-born Nast resided in New York City at the time, suggesting that he drew his image based on contemporary reports of Confederate operations in Maryland. Several of the details in Nast’s depiction are interesting in that they clearly reflect information which appeared in newspapers at the time. The first of these details is the pontoon bridge in the center-rear of the image. Nast did not assign a location to his drawing, writing in his caption that it showed “The Rebel Army Crossing the Fords of the Potomac for the Invasion of Maryland.”

The September 27 issue of Harper’s Weekly, likely based on a report that appeared in the Philadelphia Inquirer on September 9, mentioned a Union army pontoon bridge that the Rebels had captured on the Peninsula and placed at Noland’s Ferry for artillery and supply wagons. Engineers with the Army of Northern Virginia did not assemble the bridge until a couple of days after the initial Rebel crossing, however, so Nast’s drawing clearly conflated how he imagined the initial crossing must have looked with news about it that came out several days later.

Another detail worth mentioning is the men on the left side of the drawing waving their hats. Contemporary reports circulating in Maryland and Pennsylvania noted how a portion of the population sympathetic to the Southern cause greeted Lee’s army with some enthusiasm. The available evidence also hints that the closer to the Potomac a community sat the more likely its inhabitants were to support the Confederacy. Nast probably heard stories along these lines, leading him to show local sympathizers emerging from their hiding places to greet the arriving Rebel cavalry and point it north toward Frederick City.

The presence of Confederate cavalry in the column’s vanguard is a final detail to consider. Reports from Federal observers on nearby Sugarloaf Mountain noted the presence of Rebel horsemen on the canal berm as early as the morning of September 5. Frederick County residents also spotted riders in advance of the main Rebel force, men who most likely belonged to Lige White’s border cavalry from Loudoun County, Virginia. These outriders approached Frederick City ahead of the main Confederate column, with the first rider to appear in Frederick announcing that “he belonged to White’s company of border cavalry, and was the advance of Lee’s army that would soon be up.” Nast surely learned details like these from reports about the Confederate incursion spreading north in September.

Curiously, Nast’s sketch also depicts the crossing taking place by moonlight. Appearing like wraiths out of the darkness, Rebel troopers approach the Maryland shoreline in a swarm. There is menace in their appearance, reflecting the panic experienced by Unionists in Maryland upon hearing of the Army of Northern Virginia’s approach. Here Nast seems to have chosen to incorporate details about Wade Hampton’s cavalry crossing at Conrad’s Ferry on the night of September 5. Depicting the Southern army’s river crossing at night, even though it took place over a number of days and nights, struck an ominous tone that would have resonated with Nast’s anxious Northern audience. His image contained elements of fact, but the vocally pro-Union, anti-slavery Nast nevertheless used the subject to communicate fear of the ragged horde of Rebel troops that had descended on Maryland. This fact renders his drawing both a simple illustration and a complex piece of propaganda.

Redwood’s Postwar Reminiscence

Born in Lancaster, Va., on June 19, 1844, Allen Christian Redwood is the only artist of the three examined here to have fought in the war. Redwood’s pre-war connections to Maryland ran deep, perhaps firing in him a special interest in Confederate military operations in the state. The 17-year-old Redwood attended schools in Baltimore, Md., and Brooklyn, N.Y., before enlisting in the 55th Virginia Infantry when the war broke out. Following a number of engagements, Redwood found himself taken prisoner during the Second Battle of Manassas and sent to a prison camp for several months. His capture in August 1862 meant that Redwood missed the Maryland Campaign before he was exchanged in time to fight at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg. A wound received in the latter engagement knocked him out of action for a second time, but he eventually became well enough to rejoin the Army of Northern Virginia and serve out the remainder of the war.

Redwood made numerous sketches of the things he witnessed during the conflict, including the crossing of the Potomac by Lee’s army in 1863 en route to Pennsylvania. It is apparently this experience that he drew upon when making his sketch of Stonewall Jackson’s men crossing at White’s Ford. Three elements of the sketch’s content and one detail about its context make this evident. The first element is a difference between what the image purports to show and how the White’s Ford crossing is described in the historical sources. The sources state that Jackson’s men waded the ford in ranks of four with arms locked or hands held to ensure no man drowned during the passage. The men in Redwood’s drawing are not crossing in an organized column. Admittedly, the organization of Jackson’s command could have broken down as the crossing went on, but in Redwood’s case he was not present when the event occurred so he could not have known about it.

The second element is the column’s disappearance into the distance. It is a dead giveaway that Redwood did not draw what comrades might have told him about 1862, but rather what he recalled from his own experience traversing the Potomac during the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863. When Jackson’s column reached Maryland in September 1862, it took a hard left up the towpath of the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal before crossing the canal via a makeshift bridge at Lock No. 26. Redwood’s drawing shows the Rebel column moving straight up the hillside in the distance from the river.

Additionally, and this is the third revealing element, the equipment carried by the men does not match the stripped-down appearance of Jackson’s troops in the Confederate army’s first Northern offensive. According to Frank Mixson of the 1st South Carolina Volunteers, before reaching the Potomac the troops received orders “to leave all their baggage” behind. “On this trip,” noted Mixson, “we had nothing but a haversack, canteen, and a blanket or oil cloth besides the accoutrements gun, cartridge box, and scabbard.”

The men in Redwood’s drawing are exceptionally well-equipped for a Rebel column in September 1862, the month when the ramshackle state of Lee’s army reached its nadir. Several men are carrying bulging knapsacks and one man on the far left waiting to enter the river is sporting the widely-hated white leggings that most troops quickly discarded in 1861. Although possible, it is unlikely that by the time of the Maryland Campaign any seasoned member of Jackson’s hard-marching command would have still worn shoe gaiters, unless perhaps he intended to weather constant ribbing by his sharp-tongued comrades.

As for the drawing’s context, Redwood probably made the sketch at the request of his friend and student, Sophia Herrick. Redwood met Herrick after the war when she worked as an associate editor of the Southern Review magazine. She subsequently joined Scribner’s publishing house and worked as an assistant editor for The Century Magazine until her retirement in 1906. Redwood was one of the many artists that the Century Company retained to produce illustrations for their series on Civil War events and his work is featured in the multi-volume Battles and Leaders of the Civil War series that first appeared in 1884.

Volume 2 contains Redwood’s White’s Ford drawing on page 621 as an illustration for the “Stonewall Jackson in Maryland” article penned by Henry Kyd Douglas. Its appearance in the earlier volume suggests that Redwood made the sketch specifically for that subject. Then, when Volume 3 appeared, Redwood submitted an altered version of the same drawing (see page 250) captioned “Confederates at a Ford.” His changes in the image are confirmed by the presence of the soldier wearing the white gaiters in both drawings. Redwood’s drawing in volume 3, however, shows the man standing in a slightly different pose. In short, Redwood’s sketch is neither historically accurate nor drawn from memory. Redwood never made it to Maryland in 1862, forcing him to rely on his memory of events for the Gettysburg Campaign in 1863 and apply those details to his depiction of the White’s Ford crossing in 1862.

Drawings of the September 1862 Potomac Crossing: Accurate or Fanciful?

None of the sketches examined here can be considered authentic depictions of the events themselves. The best that can be said about the drawings is that each shows Confederate columns at different crossing points, those being Conrad’s Ferry (Waud), Noland’s Ferry (Nast), and White’s Ford (Redwood). Simmering tensions in Maryland raised fears in Washington and elsewhere north of the Mason-Dixon Line that the populace would rise in revolt and join the Rebel war effort once Lee’s army appeared in the state. Confederate Southerners hoped that exactly this sort of event would come to pass, bringing “downtrodden” Maryland into the Secessionist fold.

Waud’s and Nast’s images convey a sense of the drama and foreboding that attended the arrival of Robert E. Lee’s men north of the Potomac River while Redwood’s drawing presents a more straightforward, although idealized, portrait. Each image served a purpose intended at the time, but none of them captured the events as they occurred. The best that can be said about the sketches is that they fit neatly within the genre of Civil War art akin to the modern-day depictions produced by Mort Künstler, Don Troiani, Keith Rocco, and others. The drawings are evocative as illustrations and they were useful as propaganda, but relevant as depictions of the actual historical events they are not.