In October 1914, as the series of flank ing movements known collectively as the “Race to the Sea” exhausted them selves near the town of Arras in the Artois, German and French troops faced off across a narrow no-man’s-land that ran roughly along the Arras-Bethune road. Rifle pits were dug, which were then joined to become trenches, and the line hardened into one of the most violently contended stretches of the Western Front.

Travelers along that road today are left in no doubt that these few miles of sleepy French route nationale were once the scene of immense slaughter: Walled cemeteries rise like bleached islands out of rain-swept fields of wheat, and deserted country roads wander past craters whose depth and dimensions defy any plow to reclaim them.

About five miles out of Arras, the road dips and winds through the village of Souchez, before it climbs the lower slopes of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, a long, narrow promontory that rises some 500 feet out of the rolling countryside like the prow of some immense ship. Even before the Great War, this butte with its commanding view and its then-modest church were a place of local pilgrimage. Today, the fact that Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and the villages nestled in its shadow were once a vast charnel house is obvious–the flat summit, crowned by an outsize and rather hideous church and a freestanding observation tower, is awash in a regimented sea of crosses. Some 20,000 of them occupy 26 acres, and the remains of another 22,000 men are jumbled in ossuaries.

With little effort of imagination, one conjures up the time when this peaceful countryside was the scene of such unbelievable slaughter. The historical literature, limited to a few sparse memoirs or the bleak prose of battlefield narrative that records the movement of battalions, regiments, or divisions, offers little help. The Battle of the Marne in 1914 and Verdun in 1916, both of which produced a profusion of accounts, seem to fit the stereotypes of glorious victory or heroic sacrifice better than what amounted to the pointless butchery of the Artois. Those who survived tended to keep silent about their experiences. It was a battle that, in military terms, achieved nothing–and yet produced unintended consequences. If nothing else, it must be counted as the prototypical trench slaughter of the Great War.

The real objectives of the attack Vimy Ridge, rising just across a valley, and the immense northern European plain that beckoned beyond–were not reached until the end of the war. Nor did the generic name of the Second Battle of the Artois with which the high command officially baptized the offensive capture the public imagination. Only the ruins of the church that presided over the fields of sacrifice offered a sufficiently dramatic focus. As for Vimy Ridge, it would become a shrine not of the French who died on its slopes but of the Canadians who eventually conquered it in 1917.

In the late spring of 1915, General Joseph Joffre designated the unremarkable villages of Sauchez, Ablain-Saint Nazaire, and Carency nestled at the foot of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette, and those empty fields that rise gently past the straggling crossroads of Neuville- Saint Vaast toward the summit of Vimy Ridge, as the stepping-stones to his planned breakthrough on the Western Front. Why Joffre believed that this offensive would prove to be the magic one is unclear. A limited but powerful attack in the same sector in December 1914 had been repulsed, as had a spring assault on the Saint-Mihiel salient and attacks that pounded German positions in Champagne throughout February and March. In his memoirs, Joffre claims that in March 1915, when General Ferdinand Foch, commander of the northern army group, proposed a second offensive in the Artois, he thought it “premature.”

Nevertheless, by mid-April plans were well advanced for an attack set to jump off on May 1; Joffre had become convinced that the arrival of British reinforcements together with the creation of several new French divisions would free the manpower necessary for the operation. Following the battle, he justified his persistence in keeping up the pressure for six more bloody weeks by the need to come to the aid of the Russians; their front was punctured at Gorlice in southern Poland on May 2 and their armies hurled into a massive retreat. A second objective of the offensive was to prevent disruption of Italian mobilization following the decision of that country on April 26, 1915, as the French suggested unkindly, “to rush to the aid of the victors.”

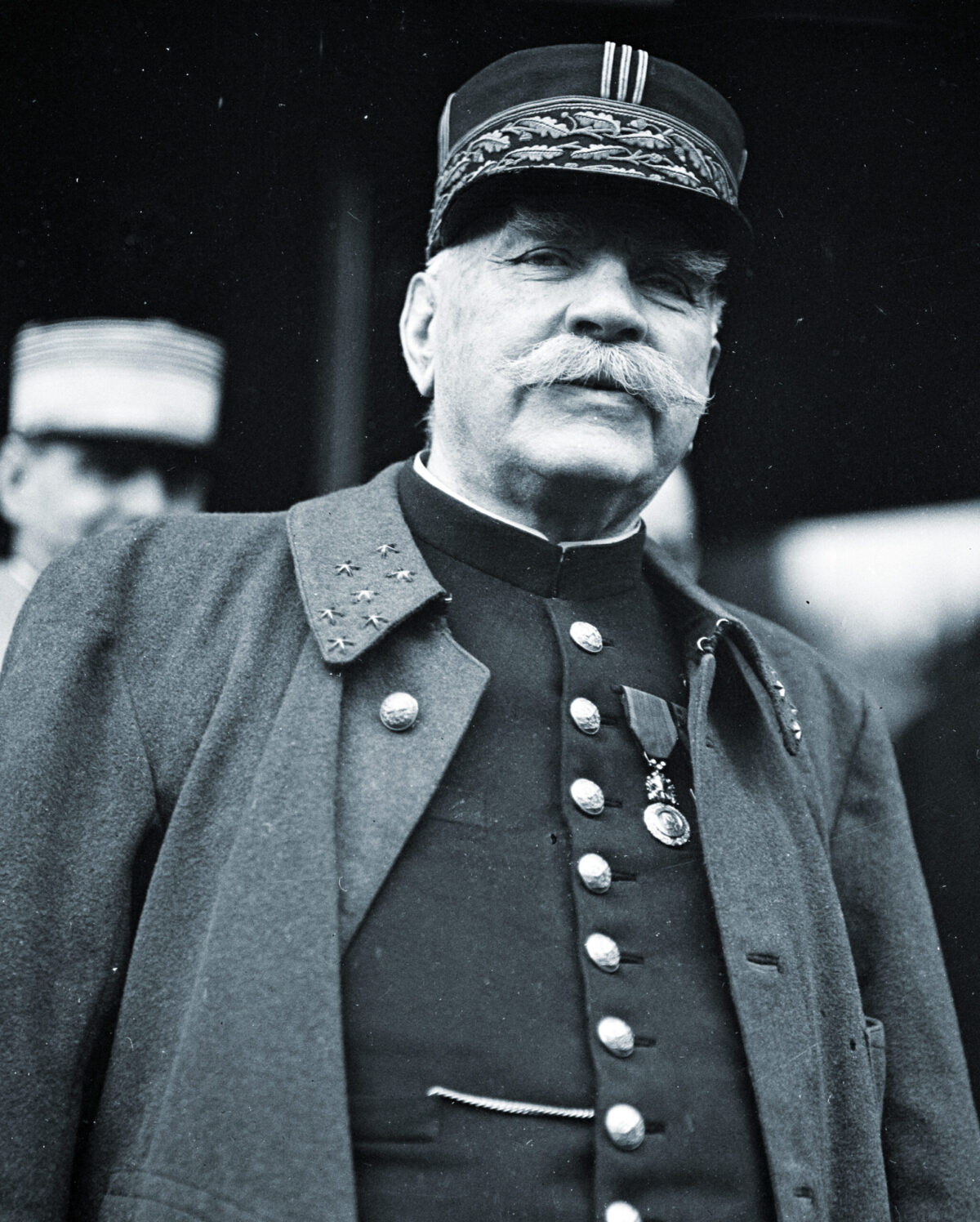

The offensive was assigned to General Victor Louis Lucien d’Urbal, the commander of the Tenth Army. Tall, with a large head, thick handlebar mustache, and gray hair cropped into a flattop, the 57-year-old d’Urbal looked every inch the soldier when he assumed his command in early April 1915. D’Urbal’s steady leadership during the Race to the Sea won him the command of the Tenth Army. His service record includes a note by Foch, who praised his immediate subordinate in the Artois as “having always shown great character, straight and uncomplicated, sound judgement, a very great authority, a firmness and spirit of decision above reproach, an open-minded and methodical attitude, the spirit of a great leader organized to achieve success. A first class army commander.”

Not everyone shared Foch’s high opinion of d’Urbal. Joffre, whose imperturbability was legendary, considered him excitable. General Philippe Pétain, who commanded the 33rd Corps charged with attacking Vimy Ridge, worried that his orders to create a “breakthrough …pushed from beginning to end with the most extreme vigor and finished off by a pursuit undertaken without delay and pressed without let up” were unrealistic given the shortage of artillery and, even more, of munitions. Colonel Marcel Givierge, serving with the codes and ciphers section in Paris, complained of the “singular mentality” of d’Urbal’s intelligence chief, who refused to forward intelligence gathered from German radio intercepts to General Headquarters.

All of this, however, is to bring to bear the selective judgment of hindsight. On paper, at least, French hopes appeared bright even though logistical problems caused them to postpone the offensive to May 7. (Last minute bad weather added another 48 hours to the wait, so that the attack ultimately jumped off on May 9.) Both the terrain and manpower appeared to favor the attackers. The German positions clung precariously to a series of ridges that formed the last natural barrier between the French army and the open plains of northern France. French troops were already entrenched on the butte of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. A successful attack there to dislodge the Germans from their last hold on the easternmost tip and the slopes of that hill would allow them to support the main thrust toward Vimy Ridge, which angled off toward the south from the foot of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette.

Strength also appeared to be in the French favor. In late April the Russians had reported the presence in the east of eight to 10 German divisions lifted from the Western Front. Their places in France had been taken by second-class territorial divisions. The attention of the German high command was obviously directed to the east. Joffre had concentrated 20 divisions in Artois opposite only six enemy divisions, which gave him a numerical edge of around 200,000 men to 60,000 Germans. But when the Germans began to detect the French buildup in April, they shifted another six divisions from Belgium toward the threatened sector.

In addition, diversionary attacks were planned by the British, who had brought their strength in France to eight army corps. And while Pétain complained that the artillery provisions were inadequate, they were the most massive yet seen in the Great War–1,200 guns, with more in reserve. By May 8, the day the French opened their preliminary bombardment, morale was high. They discounted the failure of an early–evening raid to secure a web of trenches known as the “Ouvrages Blancs” (White Works) that the Germans had spun through the chalk soil between Neuville and Carency.

At six o’clock on the morning of May 9, the French guns opened a barrage that was, by the standards of the time, of incredible ferocity. The high command calculated that their artillery could place 18 high-explosive shells on each yard of front, and the barrage appeared to realize that density of fire. At ten o’clock, troops on a 12-mile front running from Chantecler, a suburb of Arras, north to Aubers Ridge in the British sector rose out of their trenches and moved forward under a brilliant spring sunshine.

The results were almost everywhere disappointing. The British attack, which followed a minimal preparatory barrage of only 46 minutes, was the first to falter. Within an hour the British command had recognized the futility of sending waves of men against German machine-gun nests left undisturbed by the shrapnel shells that composed 92 percent of their munitions inventory. But by the time they suspended their attack, they had suffered 9,500 casualties.

That same day, the French 21st Corps attacking Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and Ablain-Saint-Nazaire had advanced barely 200 yards in the teeth of murderous German artillery counterbarrages and machine guns whose fire plunged down upon the attackers from the slopes above. At one place on Notre Dame-de-Lorette, French and Germans occupied the same trench, separated by sandbags hastily piled up. They dueled with grenades for shell holes or bits of ground known only by map designations such as sap V or point Q. To the west of Vimy, the 77th Infantry Division burrowed into the ground as German artillery fire brought down the trees that lined the Bethune road and left the wounded screaming for help. But the barrage was of such intensity that it prevented both retreat and reinforcements, forcing the troops to burrow into the earth as best they could.

At 9:35, Colonel H. Colin of the 26th Infantry Regiment observed through his trench periscope that the two mines meant to explode beneath the network of German trenches known as the Labyrinth, which sheltered Neuville, had not been pushed forward far enough, and detonated harmlessly in no-man’s land. He also began to doubt the effectiveness of the barrage when he peered over the parapet to observe its effects at the moment of maximum intensity and immediately drew the fire of German snipers whose bullets only moments before had shattered his periscope.

At 10 o’clock, when he ordered the four companies in his first wave forward, his fears were realized. No sooner had the troops left their lines than he heard the German machine guns clank to life over the noise of the regimental band, brought into the forward trench to blow the charge and then a stirring rendition of ” Les Gars du 26e” (“The Boys of the 26th”). He watched helplessly as two of his companies were entangled in the undestroyed enemy wire and annihilated. He sent the second wave forward to support the remnants of the other two companies, which had managed to reach the German lines. But concentrated machine gun fire shot down this attack before the men had jogged more than a few yards. In 10 minutes he had lost 700 soldiers. He ordered his third wave to remain where they were. One of his company commanders spent the remainder of the morning firing at German snipers who were methodically finishing off French wounded twitching in no-man’s-land. The Tenth Army’s battle diary reported laconically on May 10, “The enemy shot our wounded.”

May 9, however, was not just a day of unrelieved disaster for the French. Other elements of the 20th Corps, of which Colin’s 26th Infantry Regiment was part, managed to infiltrate Neuville–but, as the official report put it, in an “indescribable disorder,” unable to dislodge Germans who fought from the cellars and ruins along the heavily bombarded streets of the rural village.

The center of the French attack between Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and Neuville had been assigned to the 33rd Corps, commanded by General Pétain. Before 1914, he had been considered one of the French army’s maverick officers, because he preached the virtues of firepower against offensive á outrance (offensive to the limit) school of officers like Foch. The outbreak of war had demonstrated in striking terms Pétain’s professional competence. The colonel who in July 1914 had been preparing a quiet retirement had been a corps commander within a year. In 1917, he was to be named french army commander in the wake of the mutinies of that spring.

In many respects, Pétain’s assignment was the least difficult, but he prepared it intelligently and methodically. While the 70th Division on the left of his line had to deal with Carency, he cleverly screened off that village from the south and southeast rather than attack it head-on. This allowed the 77th Division in the center of his line to surge forward through German trenches badly disorganized by French artillery fire to reach the Chateau de Carleul and the cemetery of Souchez, at the foot of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. Some elements of the 77th even got as far as Givenchy, a village that flanked the Vimy Ridge; here the French were close to a breakthrough.

However, the laurels of the day fell to the French Foreign Legion, which spearheaded the attack of the Moroccan Division on Pétain’s right. Though the 2nd Regiment de marche depended administratively on the 1st Regiment of the Foreign Legion at Sidi-bel-Abbes in Algeria, it was not made up of grizzled veterans of North Africa. Rather, its ranks were filled by idealistic and often middle-class foreigners who had volunteered to fight for France and democracy in the euphoria of mobilization in 1914. Breaking with the iron tradition of the legion, these recruits had been arranged into nationally homogeneous battalions or companies of Russians, Poles, or Greeks who carried their national flags into battle.

The legion rapidly overran the Ouvrages Blancs, which had defied the French surprise attack the previous evening. Though these trenches were expected to be difficult to take, they were thinly garrisoned and had been badly disorganized by the French artillery barrage. Having seized their initial objective, the legionnaires forged ahead, impulsively, even enthusiastically, toward a shoulder of Vimy Ridge that the French maps designated as Hill 140. It was here that their real problems began. To their right, the 156th Infantry Regiment had been stopped cold before the crossroads of La Targette. The 156th was later criticized for not maneuvering to seal off La Targette and Neuville. Because they did not, the legionnaires attacking toward Vimy Ridge were subjected to a murderous flanking fire. German artillery began to find their range. Incredibly, however , the legion reached Hill 140 within the space of two hours, companies and battalions mixed together and largely leaderless.

The Swiss poet Blaise Cendrars, who had joined the legion in Paris when war was declared, gazed out over the Flemish plain that beckoned to the north. The scene to the rear was less reassuring. The attack had left a wake of desolation- stragglers, deserters, liaison officers throwing away their cumber some signaling gear, and piles of dead and groaning wounded who were strewn over the churned earth. More sinister were the groups of Germans who had escaped attention in the haste of the French advance, and who now began to reemerge from their bunkers to pot the legionnaires from the rear. Cendrars’s squad crawled back through the blasted bunkers and collapsed trenches to knife and shoot those who resisted. He discovered to his relief that many preferred to surrender rather than fight against the Foreign Legion, which prewar German propaganda had denounced as a collection of cutthroats and gangsters: ” ‘Die Fremdenlegion!’ “ Cendrars wrote. “We put the fear of God into them. And, in truth, we were not a pretty sight.”

One of the squad, Ganero–an avid hunter who, despite the terror of the attack, had retained the presence of mind to shoot a rabbit scared up by the advancing troops and fix it to his belt was apparently killed by the blast of an artillery shell. The men threw some soil over his blood-soaked body and left him, the rabbit still attached. Ten years later, Cendrars was amazed to run into Ganero in Paris–very much alive and equipped with an “American leg,” which he put on every Sunday to go to the cinema. Ganero forgave his comrades for leaving him for dead, but refused to absolve the stretcher-bearers who had stolen and eaten his rabbit.

The chaos that Cendrars witnessed to his rear was not merely a normal by product of battle, but symptomatic of a deeper confusion produced by the unexpected success of the advance. Desperate appeals for reinforcements could not be satisfied, because the high command held their reserves between five and eight miles behind the original attack lines to protect them from German artillery fire. As almost all the officers, including the regimental commander, had been killed in the attack, no one was able to organize the defense of Hill 140. The brigade commander, Colonel Theodore Pein, whose exploits as a camel corps commander had won him fame in North Africa before the war, came forward, only to be shot down by German snipers.

German shells began to slam into the ridge like runaway freight trains, spew ing out shrapnel and clouds of noxious smoke. Less comprehensible to the legionnaires was the fact that their own artillery also be gan to pummel their positions, and continued to do so, causing great carnage, despite a desperate waving of flags and signaling panels. On the plain in front of them, the legionnaires could see German reinforcements disembarking from city buses requisitioned in occupied Lille, so close that they could read the advertisement boards. Without officers, reinforcements, or machine guns, the legionnaires gave ground in the face of the inevitable German counterstroke that broke over them that afternoon.

The day cost the 2nd Regiment de marche its commander, all but one of its battalion commanders, 41 other officers, and 1,889 legionnaires, or 50 per cent of strength, but won for it the compensation of the croix de guerre. This was the first in a series of decorations that would leave the legion, whose units on the Western Front were amalgamated in the autumn of 1915 into the celebrated RMLE (Regiment de marche de la Legion etrangere), the second most-decorated unit in the French army by the war’s end.

Although the advance by Pétain’s 33rd Corps of up to two and a half miles into the German lines, with the capture of 2,000 prisoners as well as a dozen guns and almost 50 machine guns, had left d’Urbal exultant, the success was illusory. By the afternoon of May 9, the German command had already begun to recover its composure French aircraft reported the arrival of German reinforcements, the first in a steady buildup that within a few days would swing the odds heavily in favor of the defense. And as d’Urbal prepared to reinforce success by urging the 33rd Corps to advance “with the greatest speed” before the enemy could bring up his reserves, Petain demurred. In the view of the future commander of the French armies, an advance toward Vimy and the open country beyond was out of the question so long as it had to be funneled between the enemy-held villages along his flanks.

Petain won the argument in the short run. As the French prepared systematically to reduce Ablain, Carency, Souchez, and Neuville, the deficiencies of their army-and consequently, of Joffre’s strategy of breakthrough-were laid bare. Although the French had massed what appeared to be an impressive number of guns for the Artois offensive, most of them were 75s, light straight-trajectory fieldpieces created for mobile warfare, which lacked the ability to strike the enemy in fortifications or behind hills. Nor had they the power to destroy his deep bunkers. Advances were limited to around 3,000 yards, because the 75s could not support a deeper penetration.

The Artois offensive at the height of its intensity was backed by only 355 guns with a caliber greater than 75 millimeters, and many of these were of an antiquated slow-firing design. Shells were also at a premium, a situation complicated by the fact that poor-quality munitions caused barrels to rupture with increasing frequency. So artillery commanders, their casualties mount ing, slowed their rate of fire, and saw the number of gun tubes actually diminish even though five artillery divisions were sent to reinforce the front during the course of the battle. Mean while, the Germans massed their artillery at a rate that quickly left the French desperately outgunned.

Nor in 1915 were French artillery tactics very sophisticated. While the Germans created false batteries, or fell silent when French spotter planes were above so not to reveal their positions, the French took little trouble to camouflage or protect their guns. The absence of enfilade fire, as well as what one French commander called “the moral barrier of sector limits,” which meant essentially that commanders refused to deviate from rigidly established fire plans, reduced artillery effectiveness still further. French barrage patterns were so predictable that the Tenth Army command complained on May 17 that the Germans merely waited until the French barrage lifted, a sure sign of attack, before opening up on exposed French infantry. The Tenth Army command urged French gunners to “nuance” their barrages, appearing to stop to encourage the German guns to fire prematurely, and then resume their bombardment.

In close fighting, the French were at a disadvantage because of their inferiority in trench mortars and machine guns. Colin complained that his soldiers were sent to attack the Labyrinth with antique grenades armed by pulling a string. By mid-May, Pétain’s troops were so short of grenades that he ordered his engineers to manufacture petards, improvised trench bombs, to make up the deficit. While Pétain has received high marks from military historians for refusing to advance until the villages along his path could be occupied, his lack of artillery would make his follow-up attacks costly.

On May 12, the 20th Corps on his left inched its way along the plateau of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette and up its northern slopes to seize the church, or what was left of it. At the south foot of the butte, Ablain was declared a French possession, although the Germans still clung to a few shattered houses. Carency fell to Pétain’s 33rd Corps, complete with 1,000 prisoners, and Pétain prepared to seize Souchez.

However, this would prove a perilous and mostly frustrated enterprise so long as the Germans clung to Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. Attacks on May 14 and 17 designed to isolate the defenders on the slopes of the butte did little to dent enemy defenses in Souchez, and left d’Urbal seething with impatience at the cautious approach of his subordinate. The tone of his communications became increasingly strained as replacing the familiar “tu” with which he had addressed his successful corps commander after May 9 with the more formal “vous”–he urged Petain to seal off Souchez with a screen of troops and push on toward Vimy. While Pétain pretended to obey, he concentrated his artillery on pockets of German resistance that clung to fragments of Ablain and the slopes of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette. But attacks on the cemeteries of Abla in and Souchez on May 22 and 25-26 yielded minuscule advances.

The reasons for the lack of progress were fairly obvious. By May 20, the Germans had matched and surpassed the French in the weight and quality of artillery, a dominance that they maintained for the remainder of the campaign. Pétain complained that German gunners, guided with unerring accuracy by observers aloft in numerous balloons and aircraft, obliged his troops to keep to their bunkers in the daytime and slowed his attack preparations. Furthermore, attacks inadequately supported by artillery exhausted his infantry, and he asked to postpone a second push until his infantry could recover.

On Pétain’s right, the 39th Infantry Division, whose advance before Neuville had for three weeks been measured in inches rather than yards, much less miles, was relieved on May 26 by the 5th Infantry Division under General Charles Mangin. A veteran of numerous colonial expeditions including the epic march across Africa from the mouth of the Congo River to Fashoda on the upper Nile in 1898, an event that had brought France and Britain to the verge of war, Mangin was an aggressive commander who did not hesitate to risk his own skin in the front lines–he once dared one of his regimental commanders to join him in raising his head above the trench parapet during intense German sniping. His motto was “Faire la guerre, c’est attaquer.” (“To make war is to attack.”) However, at Verdun in 1916 his willingness to pitch his division into costly attacks would win him the nickname of “the Butcher.”

On June 1, after sitting for four days under constant German bombardment, the 5th Division jumped off before Neuville. For a week, the 5th did no better than their hapless predecessors in the 39th. The Germans had transformed the village houses into a web of defenses that had to be assaulted piecemeal. The deficiencies of French artillery preparation were such that on the second day Mangin called off all attacks. When he renewed them on the following day, progress was held up by Germans congregated in a single house, which was attacked by the entire 36th Infantry Regiment for a week before it finally fell into French hands. On June 5, despite intense German fire, the 129th Infantry Regiment broke into the center of the village. When a group of Germans attempted to surrender, a corporal, a cigar dangling from his lips, shot several of them out of hand, before handing the nine surviving POWs to his company commander with the recommendation that he shoot the rest if they proved a nuisance. Two days lat er the 36th finally cracked the German defenses and captured another portion of the village.

Captain J. La Chaussee led his company of the 39th Infantry Regiment through shallow trenches, over walls, and beneath collapsed roofs and strands of barbed wire to prepare the final assault to clear Neuville, his men cursing as their cumbersome packs snagged on the debris. Hardly had they arrived than General Mangin appeared, dressed in red trousers and a braided kepi. “What I want is a fuite en avant [flight forward],” he shouted at the battalion commander. La Chaussee watched as one of his sections rushed forward, only to be caught by a flanking fire from the German defenders. “One man who was out in front of his comrades was struck by a bullet at the very moment that he reached a wall, behind which he probably hoped to shelter,” La Chaussee remembered. “Disarmed by the shot, as he struck the wall with his fist crying: ‘AH!’ a second bullet hit him. He squatted down his body trembling. He held out his arms and shouted: ‘Mother!’ A third shot finished him off.” The remainder of the section, which was within a whisker of annihilation, was saved by the arrival of a soldier from an engineering unit, who broke up the troublesome German defenses with a few well-placed grenades.

On June 9, after a concentrated artillery barrage, the last defenders were cleared from the northeast corner of the village. (La Chaussee noted that, contrary to the French practice of packing the front lines, the German forward positions seemed to be occupied only by an elusive handful of grenadiers and snipers, the start of the defense-in-depth concepts that in later months were to frustrate every French offensive innovation.) The Frenchmen pulled together debris of the vill age to construct individual shelters as the German shells rained down around them–harmlessly, as it turned out, because most were shrapnel, which had little destructive power against well-dug-in troops.

The Germans had left behind three 77mm artillery pieces, 15 machine guns, many grenades, and over 1,000 corpses. But the French success had been a costly one–the cellars of the village were filled with dead and dying French soldiers whose evacuation had been impossible amid the chaos of destroyed houses. The 5th Infantry Division counted 3,500 casualties at Neuville. Once they were withdrawn to the rear, the survivors of La Chaussee’s 39th Infantry Regiment threw themselves into a wild celebration, with soldiers dressed up as clowns. One private entertained Mangin, who attended the festivities, with an original musical composition played out on his machine gun. The assault upon Neuville allowed the 20th Corps to devote its full attentions to the Labyrinth, that maw of trenches, bunkers, and shell holes that had swallowed Colin’s 26th Infantry Regiment on the first day of the attack. By June 16, after bitter, close-quarter fighting with mines and grenades, most of the Labyrinth was in French hands.

When d’ Urbal resumed his offensive on June 16, he had 20 divisions with more in reserve, supported by 800 light and 355 heavy artillery pieces, each with 800 shells; 12 German divisions faced him. This time, he prepared to exploit the expected breakthrough by keeping his reserves close to the front.

The breakthrough never materialized. For those soldiers preparing the approaches to the northwest of Notre Dame-de-Lorette for the corning offensive, the reason was obvious: They were locked in a siege war of such ferocity that no attack had a chance of advancing more than a few yards. They spent the daylight hours with forty men crammed into shelters designed for a dozen. Anyone who sought to escape the flea-ridden suffocation of the bunkers for a little fresh air invited a hailstorm of German artillery. As darkness fell, they emerged exhausted from their pestilential holes to shore up positions that had been churned and mangled by daytime bombardments, a labor interrupted by flares that obliged everyone to freeze as the shadows gradually lengthened before blending once again into the blackness of the lunar landscape, or by shelling and the ceaseless chatter of machine guns. They incorporated corpses into trench walls. A shell erupted only a few yards from the position of Corporal Louis Barthas and disinterred a body, upon which a swarm of black flies immediately coagulated. “What a stark contrast such a tempest makes in the midst of the calm serenity of a beautiful summer night,” he reflected.

On June 16, Pétain’s corps, spear headed by the Moroccan Division, did make some serious progress toward Hill 119, one of the lower slopes of Vimy Ridge across from Sauchez. They held their positions despite enfilading fire from Sauchez, which still defied the best efforts of the French to take it. The relative success of the Moroccan Division was spoiled by mutinies in two battalions of the legion. A battalion of Greeks, complaining that they had enlisted to fight Turks, not Germans, had to be forced to attack by Algerian tirailleurs riflemen with fixed bayonets. A second battalion composed of “Russians”–they appear to have been mainly Jews of Eastern European descent living in Paris, who had been cast into the legion against their will–refused to fight and agitated to be transferred out of the legion; nine of them, seven Jews and two Armenians, were executed. The mutinous “Russians” protested that they had met much anti-Semitism in the legion and preferred more congenial, and perhaps less dangerous, service in a French line regiment.

During the night of June 22-23, the advanced trenches occupied by the Moroccan Division on the slopes of Hill 119 were abandoned after Pétain concluded that they had become too costly to defend. Elsewhere the Germans, firmly entrenched, threw back the French attacks by concentrating all their artillery on the French infantry, ignoring the largely ineffective French counter battery fire, and then launching quick counterattacks. The French put down their failure to the lack of artillery and the inexperience of their junior leadership: “Our battalions often only attacked straight ahead, bravely, but without dreaming of maneuvering,” the official history concluded, and lamented the fact that ground won at the cost of so much blood was so often forfeited in counterattacks.

Though they tried to put a good face on it, the results of the Artois offensive were disastrous for the French. Since German control of Vimy Ridge was never seriously threatened, the French objective of a strategic breakthrough was never close to being realized. Nor did their attack do anything to halt the precipitous Russian retreat. In his memoirs, Erich von Falkenhayn, the German commander, devotes hardly a paragraph to the Artois offensive in the course of a long chapter on the German breakthrough in the east. The series of attacks in May-June cost the Tenth Army 102,000 casualties. And while the French estimated German losses at around 80,000, Berlin admitted to less than 50,000: “Certainly, there were deplorable losses on the German side,” Falkenhayn confessed. “But they were small in proportion to the greater dam age inflicted on several occasions upon this more numerous enemy.”

D’Urbal’s failure in Artois sent his career into a slow decline. He remained commander of the Tenth Army long enough to lead it in the Third Battle of Artois, which took place between September 25 and October 18, 1915, over much of the same ground . Sauchez was liberated, as were the last few yards of Notre-Dame-de-Lorette remaining in German hands, but at the cost of another 48,000 casualties. The hill that dominated the battlefield was a French pos session once again. But it was no more than a formless heap of shell craters, stinking, rat-infested bunkers, and decomposing corpses. The chapel that had once crowned its summit had been blasted into oblivion. The view from the summit–one of the few bits of high ground the Allies possessed on the Western Front–remained impressive, if more inaccessible than ever. It was one of the scant consolations d’ Urbal could take with him after he was relieved of command. For the rest of the war, his main duty was to inspect cavalry depots.

But the Second Battle of the Artois was an important turning point in the war, though one that was not immediately recognized. For some contemporaries like Pétain and a growing number of French parliamentarians, Joffre and Foch had failed to draw the obvious conclusion that they lacked the strength to make the breakthrough, that strategically the effect of their attacks upon German operations else where was minimal, that they should wait until their British allies had built up their strength and their own heavy artillery had come on line.

Instead, Joffre and Foch allowed themselves to be convinced that they had come within an eyelash of victory on May 9, that their failure had been technical rather than systemic: If they had possessed just a little more artillery, if the reserves had been held within striking distance of the lines of attack, if offensive operations had been pursued with audacity, surprise, and method, then their armies would have punctured the front and spilled through the breech into the enemy’s rear. “The opportunity for success is fleeting and the opportunity is lost if the reserves do not intervene on the spot,” Joffre had concluded when the battle was barely a week old. This theory would be tested in September in Champagne, with equally disastrous results.

The Second Battle of the Artois had at least two important long-term effects on the French army. First, it accentuated the trend in the French command to depend upon firepower and the “controlled battle.” This came as the Germans began to emphasize flexible small-unit tactics, which ultimately culminated in the infiltration techniques perfected at Verdun, Riga, and Caporet to before being used with initially devastating success on the Western Front in 1918.

This does not mean, however, that the French command failed to draw the “correct” lesson from their experience. After all, the storm-trooper tactics used by the Germans failed ultimately to deliver victory. But more to the point, those techniques probably would not have worked well in the French army, which lacked a tradition of devolution of command responsibility to lower levels, was less well trained and armed for trench warfare, and less able to define and disseminate a doctrine, especially one based on the trench experience of lieutenants and captains. In the French context, it was far easier for the staff “mandarins” to perfect the organization, coordination, and control of attacks than to turn practice and tradition on its head by relinquishing the control of the fighting to lower-echelon commanders. So while the French recognized that their army lacked the flexibility to allow them to seize fleeting opportunities, the ability of their military culture to deal with them effectively was limited. But in its continued reliance on these murderous offensives, the French command nearly destroyed its own army.

Second, this battle also marked the beginning of a shift from a strategy of percee, or breakthrough, to one of grignotage–the realization by the French high command that the breakthrough was not possible until German reserves had been “nibbled” away. The American military historian Leonard V. Smith has argued that this strategic shift reflected a deeper psychological change that came over the French army, as its soldiers became increasingly reluctant to sacrifice themselves for what they saw as the unrealistic goals of their commanders. This change was already apparent as early as the autumn of 1915, when attacks in the Artois and in Champagne were broken off by units on their own initiative, the first step in a series of confrontations between French soldiers and the high command over the conduct of operations, which climaxed in the mutinies of the spring of 1917. French soldiers remained committed to victory, but refused to be sacrificed in “useless violence” that brought that goal no nearer. The sacrificial elan of the first year was gone, not to return in this war–or in the next.

It was this psychological shift that was ultimately responsible for the success of Philippe Pétain as a commander. The Artois experience confirmed that in Pétain the French possessed a commander with vision, who concluded that his country was engaged in a war of attrition and that it must husband its resources, especially its manpower. But Pétain also recognized that the confidence of the french soldiers in the ability of their commanders to deliver victory had been shaken in the Artois, a confidence eroded further by the carnage of Verdun in 1916 and by the utter failure of Nievelle’s 1917 “bataille de rupture” at the Chemin des Dames, which goaded many of them into mutiny. Pétain realized that French soldiers were not against the war, merely that they opposed the way it was being fought. But for France, that recognition almost came too late.

DOUGLAS PORCH currently serves as a Professor of National Security Affairs at the Naval Postgraduate School, and is the former Chair of the Department of National Security Affairs for the Naval Postgraduate School at Monterey, California