IN LATE AUGUST 1917 A BATTERY OFFICER in the Royal Garrison Artillery serving on the Western Front wrote to a friend in England, “We have been under shell fire all day—as all days, and all nights….[They] got a direct hit on our dugout 4 days ago as we were having lunch. We were shelled this morning with 11-inch, just before breakfast….Last night three shells fell slap in the middle of my gun-pit.” The recipient of the letter was the expatriate American poet and art critic, Ezra Pound, and the correspondent the 34-year-old author and painter, Percy Wyndham Lewis. Several weeks later Lewis was at the Third Battle of Ypres, better known as Passchendaele. In his memoir of the Great War, Blasting and Bombardiering, Lewis described being at the center of the salient: “Shell after shell pounded down without intermission upon this central artery of the battlefield….Its crashing shells were just troublesome thunderbolts.”

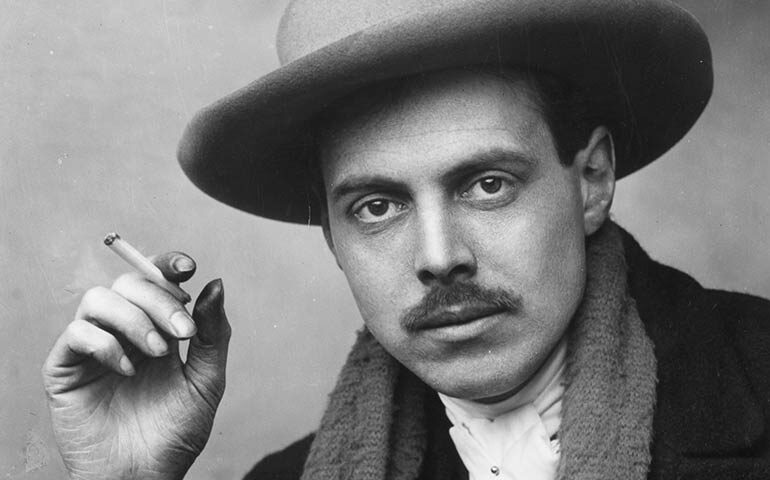

Lewis had known Pound since before the war, when they were both involved in Vorticism, the modernist movement in British art and poetry. Led by Lewis, the movement’s young artists and writers renounced traditional sentimentality in favor of a compromise between Cubism and Futurism, with geometric abstraction as their modus operandi. They considered the machine as “the greatest Earth-medium.” The mouthpiece of Vorticism, Blast, appeared for the first time in July 1914. When war broke out a few weeks later, the Vorticists welcomed it in the hope that it would destroy the old, established ways. Though they soon realized the true horror of the conflict, they did not abandon their modernist approach to war, creating a body of work that was a mix of realism and abstraction.

While Lewis was on leave in England in November 1917, a friend suggested that he apply to a war-art program spearheaded by the Canadian government. Lewis did so, and by early December he was back with his battery but serving as an official war artist with the Canadian War Memorials Scheme. He set to work rendering his experiences as an artilleryman, conscious that the Canadian art committee wanted pieces that were more representational than his usual avant-garde style. The Canadians had also commissioned him to do a painting, and A Canadian Gun-pit was the result. Painted in a realist style, it depicted two gun emplacements at the moment a gun is being readied for action. The piece disappointed him, and he called it “one of the dullest good pictures on earth.”

A couple of months after A Canadian Gun-pit was exhibited, Lewis had a one-man show of his war drawings at the Goupil Gallery in London. Titled Guns, the exhibition showcased 55 works of the suffering and injury caused by the fighting. Lewis wrote in the forward to the catalog: “I have attempted here only one thing: that is in a direct, ready formula to give an interpretation of what I took part in in France.” In a number of the pictures the human figures were represented as almost metallic abstractions, and Lewis’s colorization only added to that impression. Other canvases contained more realistic forms or mixed realism and abstraction. One of them, The Battery Shelled, showed three soldiers caught in a bombardment. It was a precursor to a monumental canvas that he would paint for a hall of remembrance that the British were planning.

In contrast to A Canadian Gun-pit, this painting—A Battery Shelled—was done in a more abstract style. While still depicting a battery of siege guns, the view is from above and there is no use of perspective; rather, the size of the figures and the tones define the space. Set amid a landscape pulverized by bombardment into a rutted, mazelike terrain impeding movement, small orange-colored figures scramble around in the middle distance, “all draggingly and as though wounded, because they know it is no good moving quickly,” Lewis wrote in another letter. The figures are angular, mechanical objects. Some are wounded, and an officer directs other men to assist a fallen comrade, while other figures service their heavy weapons. Behind them, shattered trees meld with zigzag patterns trailing through a gray-white sky, suggestive of shells in midair.

WHEN A BATTERY SHELLED WAS FIRST SHOWN at London’s Royal Academy in December 1919, visitors were perplexed by the apparent contradiction in style between the abstract human forms caught in the heat of the explosions and three realistic figures of soldiers who stand above the devastation in the left foreground of the canvas. One of them, silhouetted against a white circular stretch of sky that may denote an explosion, is smoking a pipe as he looks down with indifference toward two small figures just below him. Another of the three soldiers, his back to the viewer, also seems unmoved by the battle action. The third soldier wears a tired expression and looks away from the battle. Could he represent the artist himself? And are these men part of the action, or resting from it, even invalided? Or will they shortly be entering the fray and thereby become automatons transformed by the industrialization of the war? Art critic Richard Cork suggests that by separating these three figures from the rest of the scene Lewis may have “wanted them to signify his own postwar mood, newly awakened from the ‘sleep’ and questioning the viability of the more ‘geometrical’ idiom employed in the shell-wrecked landscape.”

This angular, jarring work reflected Lewis’s pre-war avant-garde technique, and that drew criticism. The Daily Graphic called the painting “distasteful and inappropriate.” But some reviewers were most positive: The Times’ critic felt that the artist had allowed nature to “intrude her irrelevancies, nor has he submitted to any convention of design.” Overall, the negative reception of the painting had a lasting effect on Lewis’s career.

The painting had been Lewis’s personal meditation on war. He knew the fighting firsthand and empathized with the common soldier. His composition had attempted to capture the power of technology and machine-age weaponry and its domination over men during the Great War, making humans no more than industrial waste. As Samuel Hynes wrote in A War Imagined, if the conflict had been a “nightmare in reality, then only a distorting, defamiliarizing technique could render it truthfully—art would have to become ‘untrue but accurate.’ ” A Battery Shelled certainly achieves that.

PETER HARRINGTON, a frequent contributor to MHQ, is curator of the Anne S. K. Brown Military Collection at Brown University. He writes and teaches on military art and artists.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2016 issue (Vol. 28, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: From the Avant-Garde to the Gun Pit—and Back.