Vasily Vereshchagin put himself in harm’s way to paint war as he saw it. In the process he became a pacifist.

VASILY VERESCHAGIN WAS GROOMED, FROM NEARLY THE TIME HE WAS BORN in 1842, to be an officer in the Russian military. When he was eight years old his well-to-do parents sent him to the Alexander Cadet Corps, a military school at Tsarskoye Selo, south of St. Petersburg, and three years later he entered the Sea Cadet Corps in St. Petersburg. Some 15 years later he would graduate from the naval school first in his class, but he no longer saw a life for himself in the military. He wanted to be an artist.

Vereshchagin enrolled in the Imperial Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg, and in 1864 he went to Paris to study at the École des Beaux-Arts under Jean-Léon Gérôme, the famous French painter and sculptor.

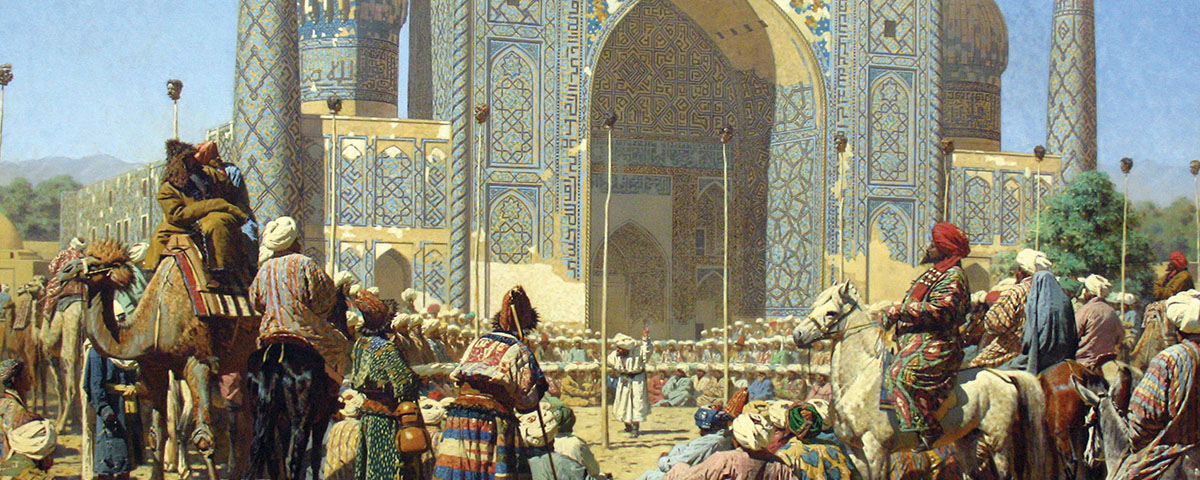

His first taste of war came in 1868, when, at age 26, he was invited to accompany the Russian army under General Konstantin von Kaufman to Turkestan (now Uzbekistan), from where Kaufman was to direct Russia’s active campaigns of expansion. (“I went to find out what war, about which I had read and heard so much, was really like,” he later said.) During the weeklong siege of Samarkand, Kaufman left to defend the Emir Muzaffar, and Vereshchagin took command of the fortress. There, some 500 Russian soldiers, half of them wounded, fought off an army of thousands. When Kaufman returned, the soldiers told him that if it hadn’t been for Vereshchagin’s leadership, they would all have been killed. Kaufman was so impressed that he awarded Vereshchagin the Cross of St. George. Vereshchagin wore it proudly for the rest of his life.

The experience marked a significant turning point in Vereshchagin’s life. From then on he repeatedly traveled to areas of conflict, often putting himself in harm’s way. “It would be impossible to achieve the aim I have set myself, to give society a picture of war as it really is, by observing battles through binoculars from a comfortable distance,” he once wrote. “I have to feel and go through it all myself. I have to participate in the attacks, storms, victories and defeats, experience the cold, disease and wounds. I must not be afraid to sacrifice my flesh and my blood, otherwise my pictures will mean nothing.”

Vereshchagin returned to Turkestan in 1869; journeyed to the Himalayas, India, and Tibet in 1873; then went back to India in 1884. Despite the difficulties he confronted—he almost froze to death in the Himalayas and fell ill with a fever as he attempted to cross the Ganges in South India—Vereshchagin managed to complete more than 150 sketches and paintings along the way. In this early work he concentrated on the brutality of war, from paintings of the dead or dying to barbarians holding up the severed heads of imperial officers, and he soon became famous for his realistic battle scenes and portraits of the people of Asia.

In one of his first major paintings, The Apotheosis of War (1871), Vereshchagin depicts hundreds of human skulls stacked in an enormous pyramid, with ravens scavenging the scene for carrion. In They Celebrate (1872), the viewer sees, from behind, a throng of people encircling a row of decapitated heads mounted on top of tall poles.

When Vereshchagin’s work was exhibited in the West, many were shocked by his realistic portrayals of atrocities. Russian and German military officials, fearing how Vereshchagin’s gruesome depictions would affect recruiting, demanded that his work be pulled from public display. Even Kaufman, his friend, accused him of falsifying history.

Vereshchagin, however, saw things the other way around; most painters, he thought, falsely glorified war. One prominent Russian artist, he wrote, typically painted each battle as the military commanders “wanted it to be known and not as it really happened.”

AS HE MATURED AS AN ARTIST, VERESCHAGIN MOVED FROM DETAILED DEPICTIONS of bloody combat scenes to more symbolic images. In The Road of the War Prisoners he uses loose, expressive brushstrokes to convey the emotional toll of the horrors during the Russo–Turkish War of 1877–1878, based on his experience of seeing thousands of Turks freeze to death as they were marched to prisoner-of-war camps. Tsar Alexander II rejected Vereshchagin’s openly antiwar creation, along with its companion piece, A Resting Place of Prisoners. In The Requiem, Vanquished, Vereshchagin shows a Russian priest giving last rites to a field of dead Muslim soldiers. When the painting was first exhibited in St. Petersburg, Russian generals became angry with Vereshchagin for empathizing with the Turks and discrediting the Russian army. Vereshchagin’s reply: “You see the naked truth.”

As one of the first painters from the West to realistically portray cultural life and landscapes across Central Asia and northern India, Vereshchagin joined other Russian Orientalists in advancing an aesthetic as well as an ideological point of view. Fascinated by the customs and traditions of the region, Vereshchagin painted it through the eyes of beggars and slaves. His Opium Smokers (1868), Beggars in Samarkand (1870), and Sale of a Slave Child (1872), for example, attracted just as much attention as his war pieces. Vereshchagin also painted such architectural landmarks as the Taj Mahal and made many portraits of Indians, nomadic people, and Muslims, as well as masterful landscape paintings, such as Glacier on the Road from Kashmir to Ladakh.

In 1871 Vereshchagin married German-born Elizabeth Maria Mary Fischer, who in the years to come would often accompany him on his travels. The couple settled in Munich—the only rival to Paris as an intellectual center for art and artists. During this time he produced paintings at a prodigious clip, beginning each day at 5 in the morning. Russian philanthropist Pavel Tretyakov, a patron of the arts who would go on to found the Tretyakov Gallery in Moscow, supported Vereshchagin by buying 138 of his paintings and about 400 drawings.

In 1872 the Vereshchagins moved to Mezon-Laffit, France, about 10 miles outside of Paris, and four years later moved into a house that Vereshchagin designed. Vereshchagin also designed a workshop on wheels he used there. By rotating the studio as the sun moved, he could always take advantage of the best light for painting.

In 1883 Vereshchagin traveled to Syria and Palestine and was captivated by the beauty of the Holy Land. The short trip he had planned turned into a two-year adventure. In his Palestine Series, which he completed at his home in France in 1884 and 1885, Vereshchagin depicted Jesus and other religious figures in a commonplace manner, stripped of their usual glorification. The series was so controversial that it disappeared from public view shortly after its European debut. The paintings were banned in Russia; in Vienna the Catholic clergy declared them heretical.

In 1888 Vereshchagin exhibited 100 of his paintings in the United States. The show, which toured for two months, was a phenomenal success, and the entire collection was sold at auction. It also would, in time, bring Vereshchagin a second wife: Lydia Vasilevna Andreevskaya, the young pianist he had invited to play Russian music in the venues of his American touring exhibition.

Settling in Moscow with Lydia in 1893, Vereshchagin began to work on a series of 20 paintings inspired by the novel War and Peace, by Leo Tolstoy. In preparation he traveled to the site of the Battle of Borodino, visited museums, met with historians and biographers of Napoleon, and read everything he could find on the subject. (Vereshchagin would also write a book about the war.)

Vereshchagin’s epic “1812” series included two paintings depicting the Battle of Borodino and 14 depicting the monthlong occupation of Moscow by Napoleon’s army. The paintings were first exhibited in 1895 in Moscow and St. Petersburg. As was his custom, Vereshchagin wanted to sell his entire series as a unit, but there were no takers. In 1902, his representatives finally managed to sell the series to Tsar Nicholas II for the equivalent of $2 million in today’s currency. After years of being rejected by Imperial Russia, Vereshchagin had finally triumphed.

In 1904, with the onset of the Russo-Japanese War, Vereshchagin traveled to the Far East, where he visited American troops in the Philippines and Russian troops in Manchuria. Vice Admiral Stepan Makarov invited him aboard his flagship Petropavlovsk. Going out on a raid the morning of April 13, they encountered Admiral Heihachiro Togo’s Japanese navy. Makarov decided not to fight, but the Petropavlovsk, in turning to retreat, struck two mines and blew up. Most of its crew, including Makarov, and Vereshchagin were killed. Within minutes the ship sank. According to eyewitnesses, Vereshchagin spent the last minutes of his life coolly painting the scene in front of him, a council of war presided over by Admiral Makarov. Miraculously, the painting was recovered almost undamaged.

“Does war have two sides—one that is pleasant and attractive and the other that is ugly and repulsive?” Vereshchagin once said. “No, there is only one war, that attempts to force the enemy to kill, injure, or take as many people prisoner as possible, while the stronger adversary beats the weaker until the weaker pleads for mercy.”

Vereshchagin used his art to speak for those who could no longer speak for themselves and asked questions, through his art, that few others dared to ask. Indeed, Vereshchagin’s voice in this realm was so resolute that, three years before his death, he was nominated for the first Nobel Peace Prize. MHQ

CATHY LOCKE is an award-winning painter, illustrator, and writer who specializes in Russian art of the 19th and 20th centuries. She teaches graduate courses at the Academy of Art University in San Francisco and is the editor of Musings-on-art.org.

[hr]

This article appears in the Spring 2018 issue (Vol. 30, No. 3) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: The Painter Provocateur

Want to have the lavishly illustrated, premium-quality print edition of MHQ delivered directly to you four times a year? Subscribe now at special savings!