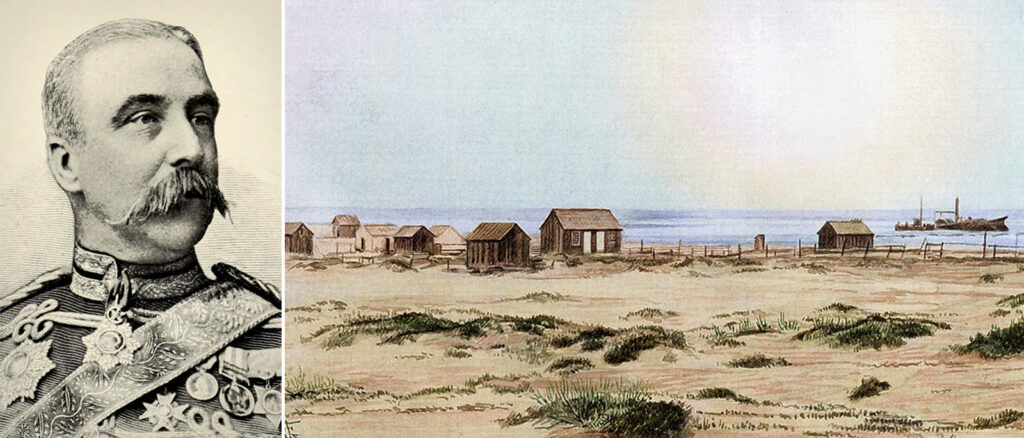

Arthur James Lyon Fremantle left Great Britain aboard a ship on March 2, 1863, headed for the northern border of Mexico. After a long voyage, the young British army officer finally arrived on April 1 “at the miserable village of Bagdad” on the Mexican side of the Rio Grande. Despite considerable speculation at the time, Fremantle was in America only as a tourist and not as an official governmental observer of the United Kingdom—the widespread uncertainty of his status undoubtedly caused by Fremantle’s choice of daily attire, a full British military uniform resplendent with a corresponding bright red jacket.

Initially, Fremantle was inclined to side with the North in the Civil War, as were many of his fellow English citizens because of an inherent disapproval of slavery. He would soon switch his allegiance to the South, however, partly because he admired the Southern reputation of gallantry and determination, and also because “of the foolish bullying conduct of the Northerners.” As Fremantle would note: “I was unable to repress a strong wish to go to America and see something of this wonderful struggle.”

As he attempted to cross onto Texas soil, Fremantle was briefly detained and questioned by a half-dozen Confederate officers. Ever the keen observer, the British citizen noted that the troopers—all from Colonel James Duff’s “Partisan Rangers,” the 33rd Texas Cavalry—were similarly attired in “flannel shirts, very ancient trousers, jack-boots with enormous spurs and black felt hats ornamented with the lone star of Texas.” Despite their unkempt appearance, the Texans treated Fremantle with inestimable kindness.

While conversing with Fremantle, Duff’s troopers lamented that they were currently unable to visit some friends across the Rio Grande, alluding to a clandestine foray they had made about three weeks earlier that now put them in jeopardy. One particularly boastful Texan excitedly divulged that “he and some of his friends made a raid over there three weeks ago and carried away some ‘renegadoes,’ one of whom named [William W.] Montgomery, they had left on the road to Brownsville.”

Fremantle could tell by the smirks on the Texans’ faces that something disagreeable had clearly happened to this individual named Montgomery.

Meeting “Ham”

About noon, Fremantle left the officers and, along with a companion, headed toward Brownsville. The foreigner noted the country was mostly flat and contained an abundance of mesquite trees. Everyone they met, it appeared to Fremantle, carried a six-shooter, although he felt there seldom seemed a need for one. The duo had traveled about nine miles when they encountered an ambulance. They were informed that one of the passengers was Confederate Brig. Gen. Hamilton P. Bee, commander of Brownsville, to which Fremantle handed over his letter of introduction originally intended for Maj. Gen. John Magruder. Upon perusing the papers, Bee disembarked from the vehicle and formally presented himself to the British subject.

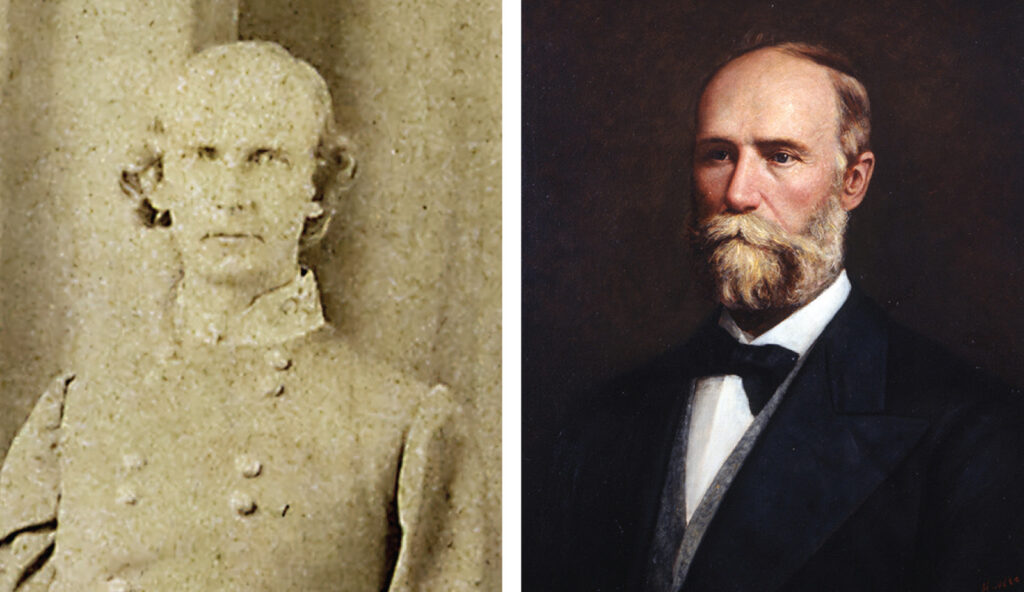

Bee had a famous brother, Barnard E. Bee Jr., who had been killed at the First Battle of Manassas and immortalized by giving then-Brig. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson the sobriquet “Stonewall.” The younger Bee, “Ham,” had accompanied his parents to the Lone Star republic decades before, and his father became part of the fledgling Texas government.

Seeing limited military service in the Mexican War, “Ham” used his political connections to secure the rank of brigadier in the Texas Militia and subsequently the Confederacy not long after the Civil War began. Bee plied the two travelers with “beef and beer in the open.” Fremantle recalled that they all talked politics for more than an hour while getting further details on the Montgomery affair. Bee elaborated that the episode was conducted without his authorization and that he was regretful it had happened.

Soon, Fremantle and his companion were on their way and, not quite 30 minutes later, came upon Montgomery’s final resting place. The victim, Fremantle wrote, “had been slightly buried, but his head and arms were above the ground, his arms tied together, the rope still around his neck, but part of it still dangling from quite a small mesquite tree. Dogs or wolves had probably scraped the earth from the body, and there was no flesh on the bones. I obtained this my first experience of Lynch law within three hours of landing in America.”

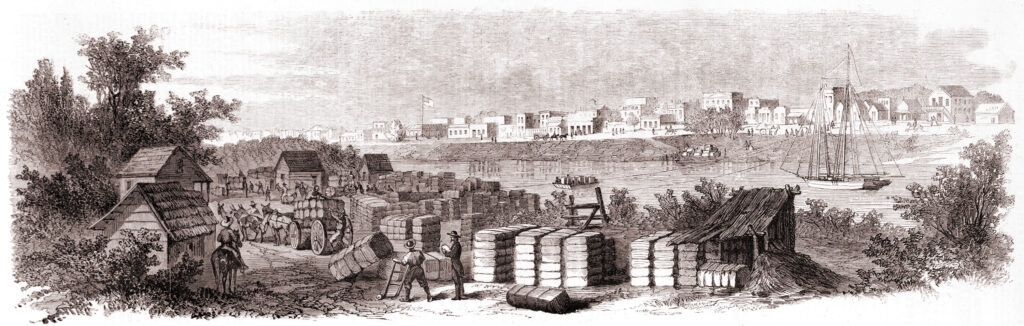

A Cross-border Conflict

The origins of the raid across the river into Mexico began with feuding Texans. Montgomery, along with Texas transplant Edmund J. Davis, had fled south of the border to start a cavalry unit composed of Unionists from the Lone Star State. Located in a foreign country, they could safely recruit members under the protection of the Mexican authorities. The Unionists became emboldened that the Texans could do nothing without illegally crossing the border to apprehend them. The Yankee sympathizers, The Tyler Reporter noted, “had just stood over the river” and “begun a series of indignities which were very provoking” and eventually “their cowardly natures—prompted them to peer at and insult our brave boys.”

Davis’ exodus to Texas had come in 1848, after the Mexican War. Ironically, one of his earliest friends was Hamilton Bee. They both sold cattle to the U.S. Army, and the future Southern general was the best man at Davis’ wedding. Before the Civil War, Davis had been elected district attorney and then district judge. His popularity and organizational skills helped get him duty as a colonel and then brigadier general of cavalry in the Union Army, followed by a postwar stint as governor of Texas.

Montgomery’s background was more shady, and he had even been acquitted in a shocking murder trial—his lawyer none other than Andrew Jackson Hamilton, future military governor of Texas during the war. Montgomery had started out as a horse and sheep rancher before elevating his portfolio to capital crimes.

Meeting in Union-held New Orleans, Davis and Montgomery were assigned to send loyal men from Matamoros to the Crescent City as recruits for the proposed Federal cavalry unit.

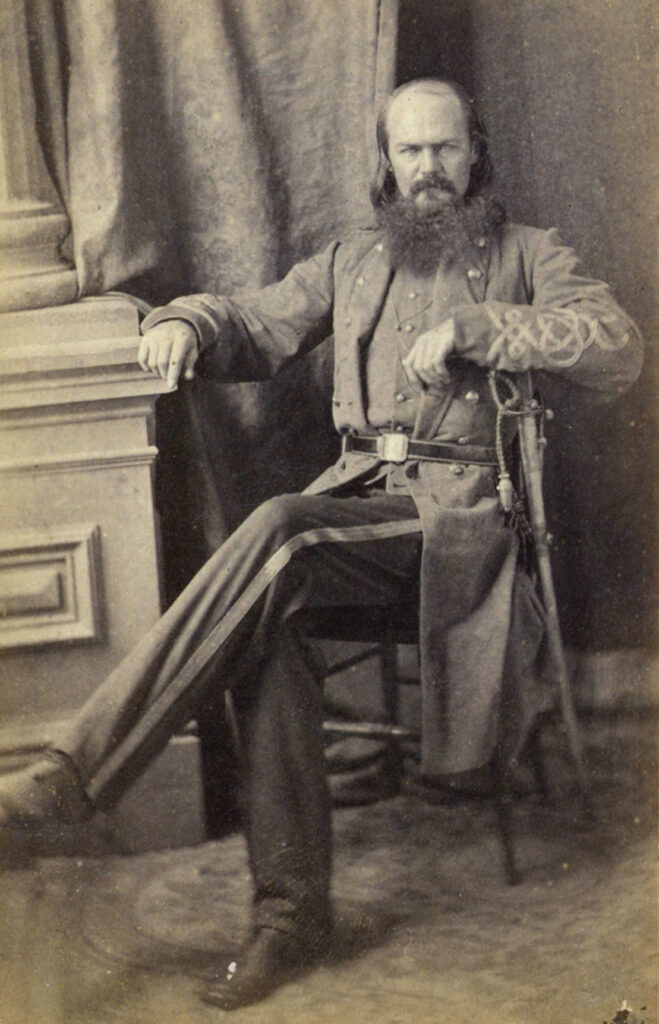

In 1864, when Fremantle had his notes published in a book, he identified the leader of the murderous gang who had captured Montgomery and Davis and had killed the former. And though his publisher refused to print the name of the culprit in the text, Fremantle’s details about the perpetrator were included in the volume. A few days after his discovery of Montgomery’s remains, the Englishman jotted down: “We were afterwards presented to ________, rather a sinister-looking party with long yellow hair down to his shoulders. This is the man who is supposed to [have] hang[ed] Montgomery.”

Frustrated by the “despicable” behavior the Unionists had displayed, the Confederates vowed revenge. One of Duff’s men, a self-described Mexican-American Confederate named Santiago Tafolla, recalled, “about midnight, Col. [George William] Chilton came from Brownsville with a small group of men. They immediately woke us up and told us to go across the Rio Grande to capture certain men there who had been harassing us daily.” The Southerners secreted themselves across the river in three small boats after receiving specific instructions from Chilton that they were not to harm anyone, especially Mexican nationals. With Chilton in the lead, the small group stormed the customs house along the riverside and pulled out Davis and “a man named Montgomery who, according to what people said, was an evildoer.”

Another of Duff’s Partisan Rangers, an Englishman named R.H. Williams, remembered that on their way to Bagdad, Chilton explained to the group that their mission was to capture Davis and other leaders of the 1st Texas Cavalry (U.S.). Noted Williams: “Now these deserters and their boasting talk…had riled the boys very much, and they were ‘blue mouldy’ to get at them.”

A correspondent accompanying the insurgents wrote: “Surrounding the house in which Col[onel] Davis was said to be, [they]…ordered [him] to surrender, and I regret to say, he did so.” But Montgomery “fought like a wild cat and wounded two of the men badly with his bowie-knife before he was overpowered.”

The Yankee sympathizers being hunted had been alerted by the accidental discharge of a Confederate’s weapon. As Tafolla revealed:

“The day was dawning and at the sound of the shot, we saw men pop up from different directions. As it was now daylight and we were on Mexican soil, we were ordered back. To do that we had to pass through the village, which by this time had been totally alarmed. So as we approached the houses, we were greeted by a rain of bullets from the houses, from the windows and from the doors. But we had received orders not to fire. Before we could reach the Rio Grande, the local judge came out to ask us why we had crossed over to Mexico. We told him we were supposed to take certain Americans prisoner, but that we had strict orders not to violate any Mexican laws.”

At the time, Chilton was swiftly moving his force back across the Mexican border; the Kentucky native was serving as Bee’s brigade ordnance officer. He gave orders to transport the prisoners to Brownsville with Montgomery’s hands tied behind his back astride a horse, while Davis was allowed to mount his ride unrestrained. To his captors, Montgomery stated, “All I ask is that I be treated as a prisoner of war.” Chilton replied that he would be treated as he deserved, a foreshadowing of Montgomery’s deadly fate. Along the route back to Brownsville, the despised Montgomery was hanged, or as The San Antonio Herald documented, “immediately went up a tree.”

De-escalation

Davis’ wife had swiftly contacted the Mexican governor, Albino Lopez, who was in the area, and explained that her husband had been abducted. Lopez immediately called for the men’s return. Bee found himself amid a potentially major international incident and feigned ignorance of the incident. A month before, Bee and Lopez—together with Confederate agent Jose Quintero—had negotiated an extradition agreement. The particulars of the accord assured the extradition of persons accused of murder, embezzlement, theft, and robbery of cattle or horses without any previous notification of the authorities on the other side of the border. Furthermore, if a pursuit of a criminal began on one side of the border and continued on the other side, the posse had permission to continue to follow them. Unfortunately, these kidnappings were not covered in the aforementioned document. The news of the situation provoked great rage in Matamoros. Groups of protesters paraded down its streets angrily shouting anti-Confederate slogans. When it was discovered that Montgomery had been killed, the Mexicans became even more upset. Lopez was so furious that he threatened to close the border and arrest all Confederate officers currently in Matamoros. Lopez followed up on his stance in a missive to Bee complaining not only about the Davis kidnapping but other less publicized incidents. He also requested a battalion of sharpshooters from the military and began organizing his own local militia in case of a martial confrontation with the Texans.

Finally, Bee relented and returned Davis to Mexico, which at least de-escalated the tensions. Quintero fired off a dispatch to the Confederate capital in Richmond, Va., informing his superiors of the peaceful resolution. He also notified Santiago Vidaurri, another governor in northern Mexico, of the incident crossing the border. Vidaurri had treasured his alliance with the Confederacy, as it greatly assisted his impoverished area.

“The bitter enemy of our cause,” Quintero reported, had been removed to Brownsville, where Montgomery would be “permanently located.” Vidaurri only seemed curious as to why it had taken the Confederates as long as it did to act on the situation.

Blame for the hanging of Montgomery continued to be debated on both sides of the river. Davis identified Sergeant H.B. Adams of Duff’s command as the person in charge of the lynching detail, and a Unionist in Mexico, Captain William H. Brewin of Yager’s Texas Cavalry Battalion, as a participant, though that accusation could not be confirmed by a corroborating witness. The Confederates tried to justify their actions in hanging Montgomery by claiming he led the forces that had killed a citizen named Isidro Vela, along with some cotton teamsters. This raid, carried out under a U.S. banner, happened in December, however, while Montgomery was busy recruiting in New Orleans.

Other Southerners accused Montgomery of murdering two men near Corpus Christi. They described Montgomery as being “of Kansas notoriety” and was considered a “noted jayhawker and murderer.” In all likelihood, Montgomery’s only true crimes were antagonizing the Confederates across the river and wounding two Confederates during his abduction.

Months later, the Federals controlled the area in which Montgomery’s remains were located. One member of the burial crew remembered: “I found the bones of Capt. Montgomery interred about one foot in the ground, except his right arm, which I found in the fork of a tree, some distance from the tree on which he was hanged.” At 3 p.m. December 19, 1863, Montgomery was given a proper military funeral in Brownsville. A soldier with the 19th Iowa Infantry witnessed the funeral procession and a stirring eulogy by Hamilton, Montgomery’s former attorney and now governor. He recalled a list of those condemned as having a part in Montgomery’s death, including Bee, Philip N. Luckett, Chilton, Brewin and Richard Taylor, who was field commander of Confederate forces in Louisiana.

Chilton was later publicly condemned for actually joining in Montgomery’s hanging, but his true crime was commanding the expedition, and in ordering the heinous execution that caused such a fiasco with the Mexicans. Both Fremantle and Tafolla positively identified Chilton as the ringleader of the hanging. Although Fremantle didn’t mention Chilton specifically by name, a glance at Chilton’s photograph would confirm he certainly matches the description the British soldier had made.

Fremantle returned to England after having achieved the adventure he sought by his travel through Texas and by witnessing the Battle of Gettysburg. His account of his trip was published the ensuing year. Seeing the writing on the wall with Vicksburg’s surrender, Tafolla deserted the Confederate Army in March 1864 and headed for the safety of Mexico. His memoirs were not published until 2010.

Richard H. Holloway, who writes from Alexandria, La., is a senior editor of America’s Civil War.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2024 issue of America’s Civil War magazine.