Christmas Day 1935 turned out to be a busy one for the 23rd and 72nd Bombardment Squadrons of the U.S. Army Air Corps in Hawaii. Stationed at Luke Field on Ford Island, inside Pearl Harbor on the island of Oahu, the soldiers spent the holiday preparing for an unusual mission: dropping live ordnance on an erupting volcano.

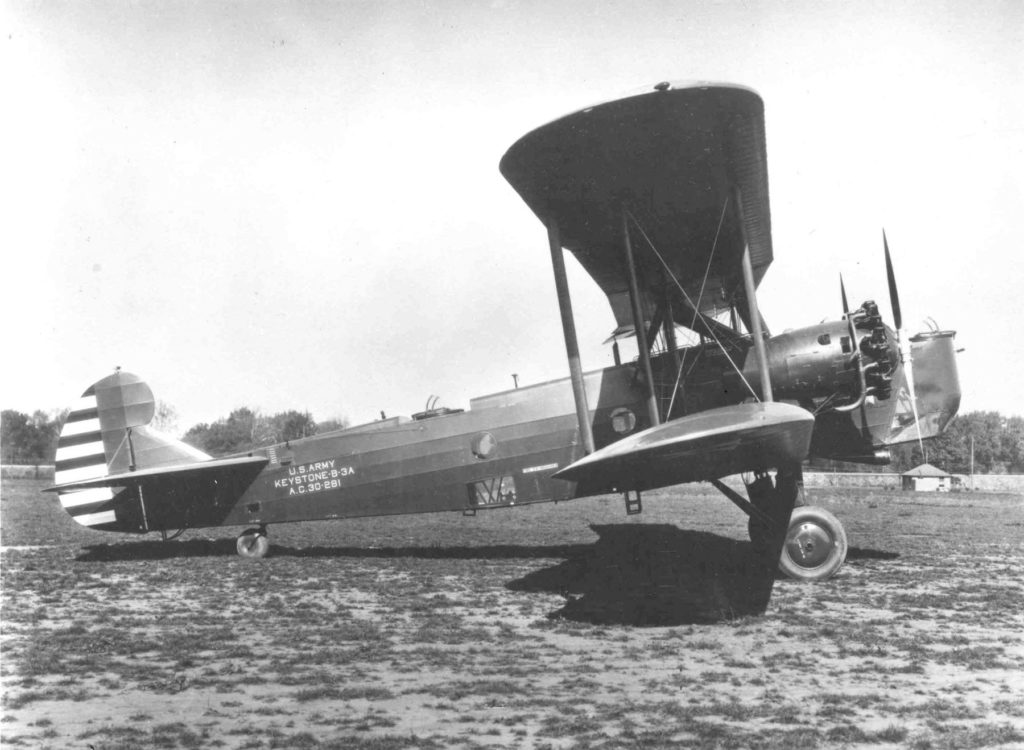

On the orders of the Hawaiian Division’s intelligence officer, groundcrews made sure the 10 Keystone B-3 and B-6 biplane bombers were ready for the first-of-its-kind operation. The squadrons would fly from Oahu to the big island of Hawaii and bomb the Mauna Loa volcano to stop it from spewing lava that threatened the community of Hilo and its 20,000 residents.

This bizarre scenario began November 21, when Mauna Loa started erupting. Thomas Jaggar, founder of the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory, became concerned by what he saw on the volcano’s north face. Red-hot magma was flowing through lava tubes at the rate of about one mile per day. It wouldn’t be long before it placed Hilo in danger. Jaggar decided to approach the Army and see if the military could do something to cut off the lava flow.

Explosives had been considered before to stop the volcano. When Mauna Loa erupted in 1881, local officials discussed the idea of using dynamite to shut off the lava flow but never followed through. Jaggar was thinking the Army could send an overland expedition to set off TNT charges, but chemist Guido Giacometti suggested that Army bombers might be more effective. Jaggar traveled to the Hawaiian District headquarters at Schofield Barracks and met with the intelligence officer there. He was Lt. Col. George S. Patton Jr., who would later gain fame as one of World War II’s most successful and controversial generals.

Patton approved the scheme and assigned the operation to the Army Air Corps’ Lt. Col. Asa N. Duncan, commander of the 5th Composite Group at Luke Field. Duncan gave orders to the 23rd and 72nd bomber squadrons, accompanied by a detachment from the 50th and 4th observation squadrons, to prepare for a unique mission.

On December 26, 10 bombers, two amphibious planes and two observation aircraft flew to Hilo Airport, where an operations base was established. The weapons and groundcrews traveled to Hilo by ship. After refueling, one of the seaplanes took Jaggar and some of the bomber pilots to identify the lava tubes he had selected as targets, located about 8,500 feet up the northeast slope of Mauna Loa.

With the objectives clearly defined, soldiers affixed ordnance to the bombers’ wings. The aircraft were light bombers built by Penn-sylvania-based Keystone Aircraft. The B-3 was a biplane powered by twin Pratt & Whitney R-1690-3 engines; the B-6 was similar, with more powerful R-1820-1 engines. (Keystone bombers, including the B-6, were the last biplanes the U.S. Army Air Corps ordered.) Each plane was fitted with 600-pound MK 1 demolition bombs, as well as 300-pound dummy bombs for aiming purposes.

The next day, the pilots flew two missions of five bombers each. They first dropped their dummy ordnance for sighting, then made final runs and released the MK 1 bombs at two locations. Ground observers reported direct hits with the 20 bombs. Lt. Col. Duncan flew in one of the observation planes to check on the results. “It was found that five bombs hit the stream itself, three in the flowing lava of the first target and two directly above the tube of molten lava of the second target,” he reported. “One of these caved in the tunnel. Three other craters were within five feet of the stream, the explosions throwing ashes into the red lava. Two others were within 20 feet of the target.” Duncan said the pilots estimated that “seven other bombs fell within 50 feet of the stream.”

The bombers had been spot-on with their attack and the magma flow began to slow. It ceased altogether within a few days, and Hilo was saved from being wiped off the map. Jaggar was pleased with the results and thanked the Army Air Corps for their efforts. “The Army, on one day’s work, has stopped a lava flow, which might have continued indefinitely and have caused incalculable damage to the forest, water resources and city,” he stated in the Air Corps News Letter of January 15, 1936.

Others, including the pilots, remained unconvinced the aerial bombings had actually made much of an effect. Scientists believed then—and still do—that the volcano likely ceased erupting on its own. Harold T. Stearns, a government geologist who flew in one of the bombers and later wrote Geology of the State of Hawaii, didn’t think the explosives had stopped the flow of lava at all. “I am sure it was a coincidence,” he wrote.

In 1942, the Army Air Forces bombed Mauna Loa again, this time to prevent Japanese vessels offshore from using the glowing lava to spot the island. Again, the results were mixed, with most volcanologists believing that the eruption stopped by itself. Unexploded ordnance from both missions was found at the site in 2020.

To this day, the 5th Composite Group—now the 23rd Bomb Squadron of the 5th Bomb Wing, stationed at Minot Air Force Base in North Dakota—is remembered for its strange encounter with Mauna Loa. In fact, the squadron’s patch, featuring bombs striking an erupting volcano, seemingly commemorates that moment in its history.

Except it doesn’t. According to historical records, an early version of the patch showing the bombs and volcano was approved by the Secretary of War on September 20, 1931—four full years before the historic bombing mission. Instead, the artwork was intended to symbolize the unit’s proximity to Mauna Loa as well as its firepower—two things that just happened to intersect in December 1935.