The U.S. Army recognized the vital outlet that music provided, but G.I.s preferred parody songs of their own invention over wholesome tunes pushed by top brass.

SINGING has long been part of military life, and the U.S. Army wanted to keep this heritage alive as it mobilized and trained more than eight million soldiers to fight in Europe and the Pacific. The army believed that group singing was important for “morale building through soldier participation” and “emotional stability through self-entertainment,” explained Captain M. Claude Rosenberry, who helped set up the army music program.

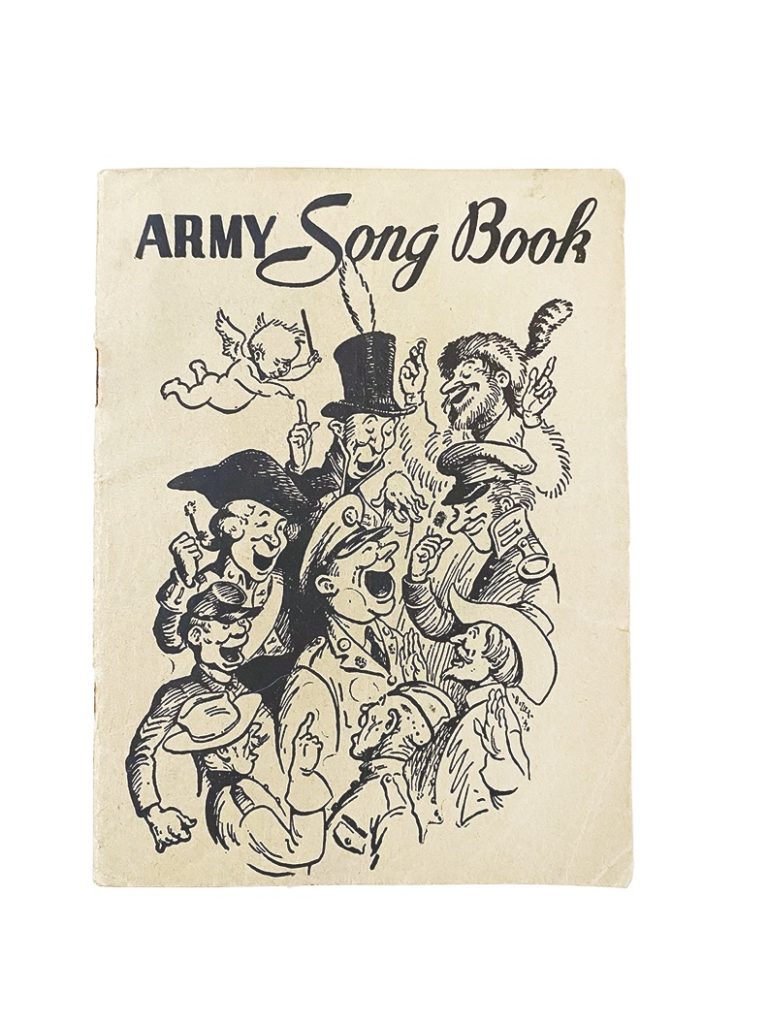

Wanting things done its way, the army adopted a regimented approach to music. In 1941, it published its official Army Song Book, containing 67 patriotic, folk, and service songs like “The Star-Spangled Banner,” “America the Beautiful,” and “Pop! Goes the Weasel,” and it expected soldiers to learn all 67 songs. The Quartermaster Corps even wrapped pamphlets of religious tunes around rations to make sure wholesome material reached the front. The army organized officially sanctioned sing-alongs and envisioned every platoon with a barbershop quartet and a “camp-fire instrumentalist (guitar, ukulele, etc.)” and each company with a song leader and “accordionist,” Captain Rosenberry wrote.

These by-the-book efforts fell flat. The army could tell men what to do, but G.I.s dug in their heels at being told what to sing and when to sing it. Soldiers, a New York Herald Tribune editorial noted, “follow only one rule in their choice of songs. They do not sing what is expected of them by their elders.” They snubbed army-organized song sessions, too. Their attitude was “spontaneous or nothing,” noted Sergeant Mack Morriss, a South Pacific correspondent for Yank magazine.

In place of songs with the army’s imprimatur, the men invented their own, making up countless verses for current hits, patriotic anthems, and well-known folk songs. Their improvised lyrics, or parodies, were often sarcastic, sometimes bawdy but always brutally honest. Their verses stretched the limits of poetic license and sometimes obliterated the boundaries of good taste, but they carried a power professional songwriters would envy and provide a glimpse, available nowhere else, into what it was like to be young, in the service, and fighting the biggest war in history.

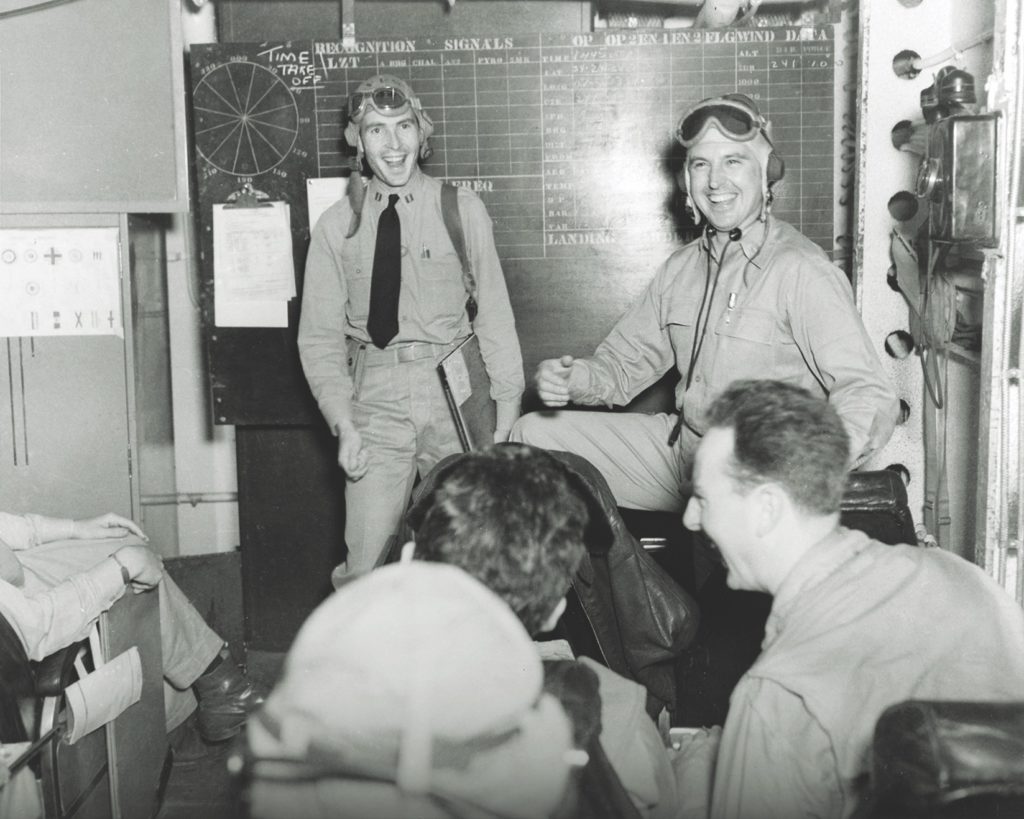

THE FATHERS OF THESE G.I.s had marched to France in 1918 belting out “Over There,” “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” and “Mademoiselle from Armentières,” and their sons carried on this tradition. They lifted their voices “at beer parties and such get-togethers…on long boat trips where there is not much else to do,” and while riding on open trucks, wrote Corporal Pete Seeger, a folksinger who served in the Pacific and whose musical career spanned more than 50 years. Collective singing made it possible for servicemen “to feel comradeship, to be happy together without being emotional, or not visibly, and thus unmanly,” said Samuel Hynes, a Marine flier in the Pacific and later a professor of literature at Princeton University.

The men’s parodies were more than a way of amusing themselves and passing the time. They served as a vital outlet to relieve wartime anxiety and the frustrations of military life. A soldier will endure almost anything “as long as he is permitted to grumble, protest and joke about his fate, to ridicule his leaders and to assert his essential autonomy and personal dignity,” noted folklorist Les Cleveland, a New Zealander who fought in the Pacific and in Italy. In fact, irreverent songs were often “the only means at their disposal for the expression of their subversive fears and frustrations,” Cleveland explained.

The men considered the offerings in the official army songbook to be lame—more appropriate for grammar-school children than for soldiers. Stateside composers churned out dozens of patriotic songs like “Der Fuehrer’s Face,” “Goodbye Mama (I’m Off to Yokohama),” and “You’re a Sap, Mister Jap,” but the G.I.s dismissed these anthems as “a lot of drivel…about as shallow as a coat of paint,” Sergeant Morriss wrote. None was “a good, honest, acceptable war song,” army cartoonist Bill Mauldin concluded. Parodies filled the void.

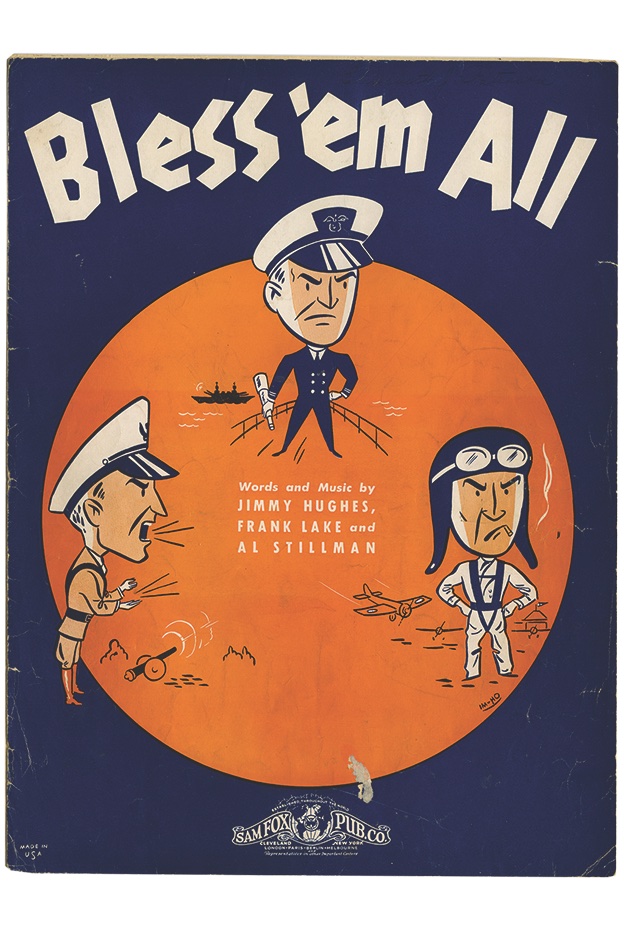

ACROSS THE GLOBE, the song American servicemen most liked to sing and parody was “Bless ’em All,” a British waltz to which they added their own lyrics. In 1917, a 37-year-old Englishman, Fred Godfrey, wrote the tune to amuse his pals in the Royal Naval Flying Service, and it became an underground favorite with British troops. In 1940, English songwriters Jimmy Hughes and Frank Lake polished it up, and it soon enjoyed wide public popularity in Great Britain. It crossed the Atlantic and was featured in American wartime films like A Yank in the R.A.F, Captains of the Clouds, and Guadalcanal Diary, and on recordings by artists like Guy Lombardo and his Royal Canadians.

Its rollicking chorus begged for group singing—“Bless ’em all/Bless ’em all/The long and the short and the tall”—and its lyrics were already charmingly irreverent toward military life: “There’ll be no promotions/This side of the ocean/So cheer up, my lads/Bless ’em all.” It was tailor-made for parodies because “any words chosen at random seem to fit,” naval intelligence officer Otis Cary explained, but its intangible appeal was what endeared it to the troops. “The song isn’t a fighting song—it doesn’t yell blood & thunder, but people sing it,” Sergeant Morriss noted: “It has guts.”

The elimination of “bless” was the first change the G.I.s made. “It shouldn’t require much imagination for even the most shy and sheltered person to know what word replaced it,” infantryman Dick Stodghill said. The four-letter substitute, unspeakable in polite circles, was a staple of the G.I. lexicon. Servicemen would have been “virtually speechless” without it, Private Raymond Gantter recalled, and Robert Leckie, a Marine who served in the Pacific, said he heard it “from chaplains and captains, from Pfc.’s and Ph.D.’s.” Its use was so automatic that many servicemen home on leave slipped up at the dinner table and asked “a younger sister or sweet old grandmother to ‘pass the f–king butter,’” mortarman John B. Babcock recalled with a chuckle. This word—and others like it—permeated the G.I. songs, which Life magazine called “mass vocal scatology.”

It would be a mistake, however, to see this language as simply the product of an all-male environment free from civilian restraints. Like the parodies themselves, the forbidden words served as safety valves, “precious as a way for millions of conscripts to note, in a licensed way, their bitterness and anger,” said Lieutenant Paul Fussell, later a professor of literature at the University of Pennsylvania. By singing “f–k ’em all,” the men could blow off steam, and the “’em” could denote whoever or whatever was aggravating them. Among those who agreed was General George S. Patton, who believed “an army without profanity couldn’t fight its way out of a piss-soaked paper bag.”

Pilots used “Bless ’em All” to voice their anxiety about death, more easily acknowledged under the guise of humor: “No lilies or violets/For dead fighter pilots/So cheer up, my lads” and “No future in flying/Unless you like dying/So cheer up, my lads.” With there-but-for-the-grace-of-God-go-I humor, rear-echelon troops poked fun at their frontline brethren—“They sit in their trenches/And think of their wenches/So cheer up, my lads”—and Marines showed macho pride: “So what if we suffer?/Marines have it tougher/So cheer up, my lads.” Sailors mocked the indignity of the periodic examination of their genitalia for venereal disease—“You’ll get no erection/At ‘short-arm inspection’/So cheer up, my lads”—and glider troops derided their aircraft: “We are lucky fellows/We’ve got no propellers/So cheer up, my lads.”

Married men sang of the fear that their wives in the States might be doing more than keeping the home fires burning—“Our future’s a problem we can’t figure out/Hope that our wives are alone in their beds”—and sailors ridiculed the officious and annoying junior officers arriving from the States: “They’re salty as hell/And stupid as well/Be sure and salute them, my mates.”

Soldiers and Marines mocked the arrival of the U.S. Navy—“In 10,000 sections/From 18 directions/Oh Lord, what a f–ed-up stampede”—and Marines bemoaned the sore subject of inaccurate tactical air support: “They bombed out two donkeys/Five horses, three monkeys/And seven platoons of Marines.” One version, crafted by crewmen of B-17 Flying Fortresses to describe returning from a tough mission, embodied the grimmest of humor: “They say there’s a Fortress just leaving Calais/Bound for the Limey shore/It’s heavily laden with petrified men/And stiffs who are laid on the floor.” The variations of “Bless ’em All” were as endless as the men’s limitless ingenuity.

ANY TUNE WITH A well-known melody was fair game, and making up new lyrics for old songs was another army tradition. In the First World War, for example, doughboys had modified “It’s a Long Way to Tipperary,” a popular marching tune, to “That’s the Wrong Way to Tickle Mary” and had improvised dozens of bawdy verses for “Mademoiselle from Armentières,” one of the best-known songs from the earlier war.

The parody process was Darwinian, and only the best versions gained traction. Explained Pete Seeger: “a parody, unless it is a good song in its own right, will not catch on and last.” He estimated that most of these ditties were “sung for a laugh once or twice…and then forgotten.” They were rarely written down, but the good ones were spread by word of mouth in “a genuine oral tradition, like folk ballads,” Samuel Hynes noted. The usual inspirations, Seeger said, were “disgust for war, and the army (or navy),” and Hynes listed the most common topics as being military life, senior officers, sex, and death. Whatever the subject, all were “comic, or were intended to be,” Hynes said, and the men sang them “humorously, half cynically, never mournfully,” folklorist A. S. Limouze explained. There’s no “official” version of any of these songs because the men adapted each to fit local circumstances and were constantly modifying the lyrics.

Soldiers weren’t trained singers, and many had trouble carrying a tune, but they substituted enthusiasm for lack of vocal talent. “When the average group of soldiers burst forth in song, it makes a chorus of tree frogs sound like grand opera,” Stodghill remembered. Listening to one sing-along, Morriss noted in his diary that “those guys can’t sing sober and even with a guitar they can’t sing drunk. But they sure are trying.” Sometimes, however, things clicked. Seeger, whose musical career took him to concert halls and recording studios, recalled a song session in 1943 at Keesler Field, Mississippi, during which nearly 40 men crowded into the tile-walled barracks latrine. The acoustics were perfect, Seeger said, and the result was “some of the best music I ever made in my life.”

Another favorite song for the creative process was “The Battle Hymn of the Republic,” a Civil War anthem that appeared in the official army songbook—but not in the way the G.I.s sang it. Airborne troops whistled past the graveyard about a paratrooper whose chute failed to open—“Gory, gory/What a hell of a way to die/And he ain’t gonna jump no more”—and sailors griped about shipboard life—“Holy Jesus/What a hell of a way to live/Then we ain’t going to sea no more.”

Soldiers ridiculed General Douglas MacArthur’s perceived penchant for pompous pronouncements—“Mine eyes have seen MacArthur/With a Bible on his knee/He is pounding out communiques/For guys like you and me”—and airmen groused about their branch of the service —“Ain’t the air force f–cking awful?” The best-known “Battle Hymn” parody, popular in all theaters and among all branches of the service, reflected the sarcasm of men itching to return to civilian life: “When the war is over/We will all enlist again.”

Another popular number was “Down in the Valley,” a well-known folk song recently recorded by the Andrews Sisters, a prominent vocal group. Bomber crews lamented dangerous missions over Germany—“Down the Ruhr Valley/Valley so low/Some chair-borne bastard/Said we must go”—and joked about their fear of being shot down and taken prisoner: “Write me a letter/Send it to me/Send it in care of/Stalag Luft III.” Transport pilots sang of the extreme danger of flying fuel and other supplies over the Hump, as they called the Himalaya Mountains: “This is the story/Of a Hump pilot’s life/For a gallon of gas, boys/He gave up his life.”

The men dusted off “Mademoiselle from Armentières” to mock the publicity given to female soldiers (WACs) and sailors (WAVES)— “The WACs and WAVES will win the war/So what the hell are we here for?/Hinky, dinky, parlez-vous”—and to grouse about any state where they had trained: “—– is a hell of a state/Asshole of the 48/Hinky, dinky, parlez-vous.”

Some parodies poked fun at the men’s own courage. Portraying themselves “as a band of ignominious, self-seeking cowards rather than as valiant, battlefield heroes” was good for a laugh, folklorist Les Cleveland explained, and acted as “a comic demolition of the entire military enterprise.” B-17 crewmen sang of their wish for a mechanical problem to send them back to their base before they met the enemy—“F–k the Flying Fortress/And pray that she’ll abort/We’d rather be at home/Than in the f–king Flying Fort”—and of another inglorious way to end a mission: “We dropped our bombs in the ocean/Which nobody can deny.” In “I Wanted Wings (’Til I Got the Goddamn Things),” a song concocted by Chicago Sun correspondent Jack Dowling, airmen urged discretion over valor: “You can save those goddamn Zeros/For those other goddamn heroes” and “I’d rather be a bellhop/Than a flier on a flattop.” They realized, they sang, that “there’s one thing you can’t laugh off/And that’s when they shoot your ass off.”

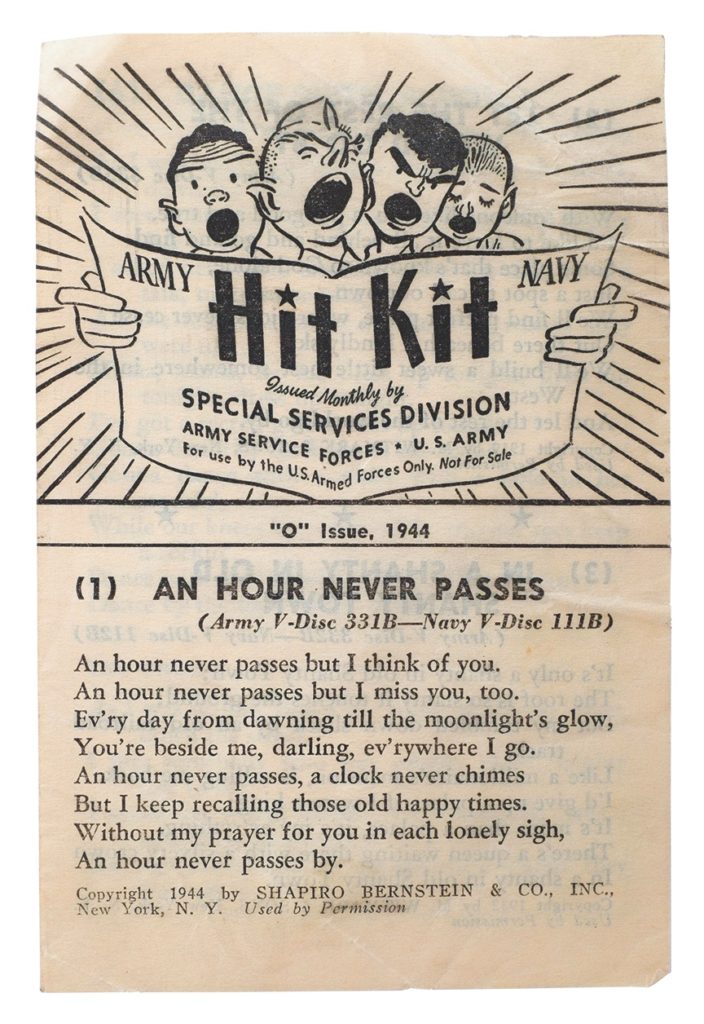

THE ARMY MADE VALIANT EFFORTS to bring the music currently popular on the home front to the troops overseas. It distributed thousands of “Hit Kits,” monthly bulletins of the lyrics for popular songs, and “V-discs,” recordings of what it called “current and favorite songs and marches.” It even shipped wind-up phonographs overseas to enable the troops to play the V-discs. The men quickly went to work on the new tunes.

Airmen doctored up “As Time Goes By,” featured in the 1942 film Casablanca. They sang about the danger of antiaircraft fire—“You must remember this/The flak can’t always miss”—and the Fifteenth Air Force in Italy mocked the Eighth Air Force in England as publicity hounds: “It’s still the same old story/The Eighth gets all the glory.”

G.I.s used “Don’t Fence Me In,” popularized by cowboy star Roy Rogers, to ridicule paper-pushers happy to spend the war safely in the States—“Let me rest at my desk/With the pencil that I love/Don’t ship me out”—and servicewomen converted “Pretty Baby,” a ragtime era hit, into an ode to the surefire ticket home: “If you’re nervous in the service/And you don’t know what to do/Have a baby, have a baby.” For infantrymen, “Wedding Bells Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine,” a popular standard, became a tribute to buddies lost to German 88mm artillery shells—“Eighty-Eights Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine”—and fliers used it to eulogize comrades shot down by German Me 109 fighter planes: “Those Messerschmitts Are Breaking Up That Old Gang of Mine.” A parody of “White Christmas,” a signature song of crooner Bing Crosby, targeted the men’s longing for female company: “I’m dreaming of a white mistress….”

Even the service songs were fair game. “The Air Force Song,” for example, was used to mock military bureaucrats—“Here we go/Into the file case yonder/Diving deep into the drawer”—and Marines used their anthem to note a dubious achievement: “We have the highest VD rate/We’re United States Marines.”

Another genre of soldier songs extolled the virtue (or lack thereof) of exotic women in faraway places. Two favorites were “Dirty Gertie from Bizerte” (who “hid a mousetrap ’neath her skirtie”), and “Filthy Annie from Trapani” (who “stashed a razor up her fanny”). Rival temptresses were “Stella, the Belle of Fedala,” “Luscious Lena from Messina,” and “Venal Vera from Gezira.” These titles were often more intriguing than the actual songs.

Oddly, few songs showed hatred for the enemy. In fact, these verses directed more venom and humor at their own officers than the Germans or Japanese. One exception was a takeoff on the “Colonel Bogey March,” a British tune later immortalized in the 1957 film The Bridge on the River Kwai. It mocked the alleged anatomical peculiarities of the Nazi leaders: “Hitler has only got one ball/Göring has got none at all.”

Most commanders tolerated the parodies. They understood the need to gripe, grouse, and blow off steam, and older officers undoubtedly recalled with fondness the irreverent tunes they had sung back in 1918. One outlier was by-the-book Colonel Eugene R. Householder, a 59-year-old West Point graduate who commanded an air force training center in Atlantic City, New Jersey. In 1943, he banned nearly a dozen of the soldiers’ songs because, he said, they impugned the men’s courage and encouraged drinking. Among the tunes he outlawed were “I’ve Been Working on the Railroad” and “The Beer Barrel Polka.” The men rolled their eyes, and Householder’s edict soon became the target of parodies, the New York Times reported.

The U.S. Post Office also disapproved. In 1943, an author named Eric Posselt published a book entitled Give Out!, containing what he called authentic soldier songs and what Time magazine described as “the salty songs roared by men away from women.” Postal authorities took one look, labeled the book “lewd and obscene,” and banned it from the U.S. mail. An anonymous reviewer from Yank magazine shook his head in disbelief, saying many of Posselt’s songs sounded as if they’d been written by public-relations officers or Sunday school teachers.

J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI saw one ditty—“Gee, But I Want to Go Home”—as part of a subversive plot to make soldiers homesick. In reality, it was nothing more than good-natured griping about army chow: “The coffee that they give you/They say is mighty fine/It’s good for cuts and bruises/And tastes like iodine.”

On occasion, a song reflected true bitterness. In 1944, Lady Astor, a sharp-tongued member of the British Parliament, reportedly called Allied troops in Italy “D-Day dodgers” because they hadn’t taken part in the Normandy landings. It’s uncertain if Lady Astor actually did say this, but British, American, and Canadian soldiers in Italy believed she had. They were irate because they had suffered greatly and endured heavy losses in the Italian campaign, which lasted more than a year and cost more than 300,000 Allied casualties. British troops used “Lili Marlene,” a German love song as popular with Allied troops as with the enemy, to skewer the viscountess, and this parody caught on with G.I.s, too.

The troops bluntly told Lady Astor what they thought of her: “You’re England’s sweetheart and her pride/We think your mouth’s too bloody wide.” They described, with biting sarcasm, their living conditions—“Sleeping ’til noon and playing games/We live in Rome with lots of dames”—and the fighting in Italy: “We landed at Salerno, a holiday with pay.” But to them, the enduring image was the crosses over the graves of their fallen comrades: “Heartbreak and toil and suffering gone/The boys beneath them slumber on/They are the D-Day Dodgers/who’ll stay in Italy.”

After the war, the G.I.s’ lyrics for “Bless ’em All” and other tunes were largely forgotten, as veterans seemed reluctant to disclose to their friends and families the verses they had sung overseas. Maybe the rough language embarrassed them, or perhaps they feared civilians would misunderstand their sardonic wartime humor. There was no reason, of course, to worry either way, for these songs stand as a testament to the wit, resilience, and spunk of those who carried the day at a pivotal moment in history. ✯

![]()

MISS POPULARITY

In the summer of 1943, the surprise hit song among G.I.s in the Mediterranean Theater was “Dirty Gertie from Bizerte,” which Life magazine called the saga of a “mischievous siren [who] lured her boy friends to their undoing.” Among the diabolical tricks recounted in the song’s lyrics, Gertie “hid a mousetrap ’neath her skirtie.”

Bizerte was a city in North Africa that the Allies had liberated earlier that year, and everyone assumed “Dirty Gertie” had originated there. Some G.I.s even claimed to have met the real Gertie, and another rumor spread that the song was really a tongue-in-cheek tribute to a mannequin—the only female companionship soldiers had been able to find in the war-torn city. But the truth was far stranger.

“Gertie” was actually the brainchild of Private William L. Russell, who had never set foot in North Africa. In November 1942, Russell, who had dabbled in poetry as a student at Cornell University, had dashed off the verse while nursing a hangover at Camp Lee, Virginia. He had seen Bizerte in the news and thought the name had a nice ring to it. Russell sent his eight-line poem to Yank magazine, which published it in its column of G.I. poetry.

Over in North Africa, Sergeant Paul Reif, a composer in civilian life, saw Russell’s published poem. He set it to a simple fox-trot melody, and Sergeant Jack Goldstein added a few verses. Soon, Josephine Baker, an African American singer who had gained fame in the cabarets of prewar Paris, was singing “Dirty Gertie” to entertain the troops. The men loved it and, soldiers being soldiers, they quickly cooked up their own scandalous verses.

Back in the States, Russell, now stationed at Camp Edwards, Massachusetts, was flabbergasted that his poem had become a hit song because, he admitted, he himself couldn’t carry a tune or even whistle one. As for the racy lyrics, all he would say was, “Mother isn’t very proud of Gertie.” Nevertheless, Russell smelled opportunity and traveled to New York City to pitch his song. Music publishers were interested, hoping the ditty would become as popular at home as it was with G.I.s. The salty lyrics, however, would never pass muster on American airwaves, so they had to be cleaned up. “Dirty Gertie” became “Flirty Gertie,” and instead of hiding a “mousetrap ’neath her skirtie,” she was simply “purty, purty, purty as can be.” Alas, the spic-and-span Gertie lacked the allure of the saucy one, and the song never became a big hit back home. ✯

—Joseph Connor

This article was published in the February 2022 issue of World War II.