The Army has awarded a posthumous honorary promotion to the service’s first Black colonel, elevating him to brigadier general more than 100 years after his death, Army Times has learned.

Col. Charles Young’s career, which stretched from his West Point graduation in 1889 to his forced medical retirement in 1917 that kept him from fighting in World War I, “broke new ground time and again,” said Army Secretary Christine Wormuth in a statement to Army Times confirming the promotion.

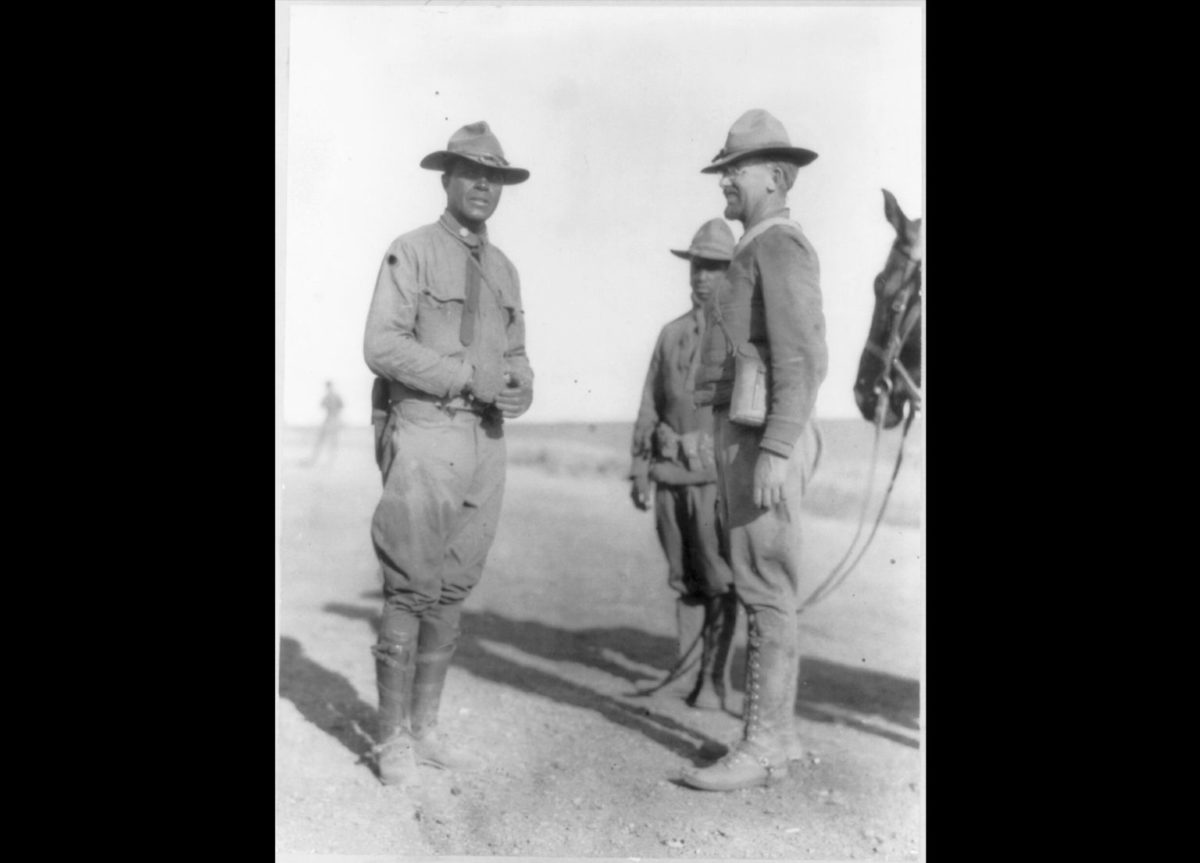

An experienced cavalry officer who was wounded in Liberia in 1912, Young was found medically unfit for brigade command — and promotion to brigadier general — in 1917. That’s despite having the recommendation of Gen. John J. Pershing after Young demonstrated his prowess as part of the 1916 U.S. incursion into Mexico.

Wormuth acknowledged that “discriminatory practices not only held him back but forced him into retirement.”

Wormuth expressed her pride that “the Army redressed that wrong [recently] with a long overdue posthumous, honorary promotion.” She will preside over a promotion ceremony “at West Point this spring — where his Army career first started as the Academy’s third Black Graduate.”

Charles Young: The Army’s first black colonel

The promotion was effective Nov. 1, 2021, Wormuth said, and Young’s descendants learned of it in January.

It comes after decades of lobbying from Young’s descendants and Black organizations like the Omega Psi Phi fraternity, which inducted him as an honorary member in 1912.

“We’re euphoric…It actually happened. It’s almost like a miracle,” said Renotta Young, a member of the officer’s family, in a phone interview with Army Times. “This was a wrong that has finally been corrected.”

Young’s trailblazing career and legacy

Charles Young’s military career began when he earned an appointment to West Point. In 1889, he became the third Black man to graduate and become an Army officer.

He served as one of America’s “buffalo soldiers” in the mostly-black 9th Cavalry in Nebraska and Utah during his early career.

Young’s next assignment was as a professor of military science at Wilberforce University near Dayton, Ohio — one of the nation’s oldest historically-Black institutions. There, he became acquainted with intellectuals like W.E.B. Du Bois.

Young’s family home in Ohio became a National Historic Landmark in 1974. It was added to the National Park Service as the Charles Young Buffalo Soldiers National Monument in 2013.

Young commanded a battalion of Ohio volunteers that remained in the U.S. during the 1898 Spanish-American War, but he deployed to the Philippines in 1901 as the commander of I Troop, 9th Cavalry, where he saw combat against local insurgents.

After returning to the U.S., Young would make history as the first Black superintendent of a national park when he took a short-term assignment as the chief of Sequoia and General Grant National Parks in northern California.

In the decade before World War I, Young completed two squadron commands and served as a defense attaché, first to Haiti and the Dominican Republic, and later to the western Africa nation of Liberia in 1912. He was shot in the arm and wounded there in a firefight between Liberian troops and a rebellious tribe.

Young, by then a major, completed his tour in Liberia in 1915 and returned to the U.S. as a luminary in the Black community. He received the Spingarn Medal from the NAACP in 1916 for his work to help organize and train the Liberian police force. The medal is currently on display at the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African American History and Culture in Washington.

His profile rose even more after his successful stint commanding 2nd Squadron, 10th Cavalry, during the Army’s Punitive Expedition that invaded Mexico in response to deadly raids by guerilla leader Pancho Villa.

Young’s troops defeated a contingent of Villa’s forces on March 31, 1916, and also fought off Mexican government soldiers the following month to save another U.S. cavalry detachment that was surrounded.

After his successes in Mexico, Young was promoted to lieutenant colonel and was on Pershing’s short-list of leaders who deserved brigade command based on their performance in the expedition. He was promoted to colonel — becoming the first Black officer to reach that rank — and underwent a medical exam to evaluate him for command.

The doctors found that his kidneys were likely damaged, but two medical boards recommended that the issues be waived in order to allow the experienced leader to fight in America’s biggest conflict since the Civil War.

War Secretary Newton Baker suggested a medical retirement instead, and the historical record suggests that a Mississippi senator had complained to President Woodrow Wilson about white officers being forced to serve under the command of a Black man. Young’s medical condition represented a convenient way to solve that problem, argued historian David Colley.

Black organizations like the NAACP protested the decision, and in an effort to prove his fitness, Young rode nearly 500 miles on horseback from Wilberforce all the way to Washington in 1918.

He was put back on active duty in November of that year, but ultimately did not receive an overseas command or promotion. He instead led a training unit and then later returned to Liberia in his former role as attaché.

Young fell ill while on duty in Nigeria in late 1921, and he died in Lagos on Jan. 8, 1922. His body was returned to the U.S. around a year later, and he was buried in Arlington National Cemetery.

Renotta Young, one of his descendants, described him as a “Renaissance man” who “persevered and loved his country.” She helps run a foundation that honors his life and preserves his legacy while supporting youth development and other educational programs.

Renotta Young, whose grandfather was the officer’s first cousin and confidante in Wilberforce, wants to see the Army continue to make progress on improving the experience of Black troops as well. She said in her phone interview with Army Times that “many of the things that he went through still exist,” such as base names that honor Confederate troops and a military justice system that disproportionately punishes Black troops.

She hopes “that this [overdue honor] will spur” Army officials to “recognize that it is for the good of society to identify individuals who can and will make a difference without any aura of discrimination.”

This story contains information that originally appeared in an article by David Colley in the March 2013 issue of Military History magazine. Originally published on Military Times, our sister publication.