Relations between top Army and Marine commanders became testy in early 1968 as generals with clashing views on battle tactics attacked not only the enemy but also each other. The squabble was focused on the northernmost region in South Vietnam, the only part of the country with a heavy concentration of both Army and Marine units.

The spark for the feud was lit when Army Gen. William C. Westmoreland, commander of all U.S. combat forces in South Vietnam as head of Military Assistance Command, Vietnam, decided to add a top Army commander to the northern region, where a Marine general was already in charge.

In the South Vietnamese army, the northernmost region of the country was under the command of its I Corps unit and designated the I Corps Tactical Zone, a collection of five provinces. I Corps was one of four military zones organized in the South during the late 1950s and early ’60s.

The American unit in charge of U.S. troops in the I Corps Tactical Zone was the III Marine Amphibious Force, formed in May 1965, after the Marine landing at Da Nang in March brought the first U.S. ground combat unit to Vietnam. That unit, the 3rd Marine Division, was joined by the 1st Marine Division in February 1966. The 3rd Marine Division focused on the two provinces closest to the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Vietnam, while the 1st Marine Division handled I Corps’ lower provinces. Marine Lt. Gen. Robert E. Cushman took command of III MAF in June 1967.

Westmoreland, concerned about increased activity by the North Vietnamese Army in late 1967, prepared contingency plans in January 1968 for a second high-level I Corps command, headed by an Army general. Army historian Graham A. Cosmas observed that Westmoreland thought there would be a major NVA offensive and “did not trust III MAF to be able to control the battle.” On Jan. 31, just days after Westmoreland’s plans were unveiled, the communists launched their Tet Offensive, a series of near simultaneous attacks all across South Vietnam.

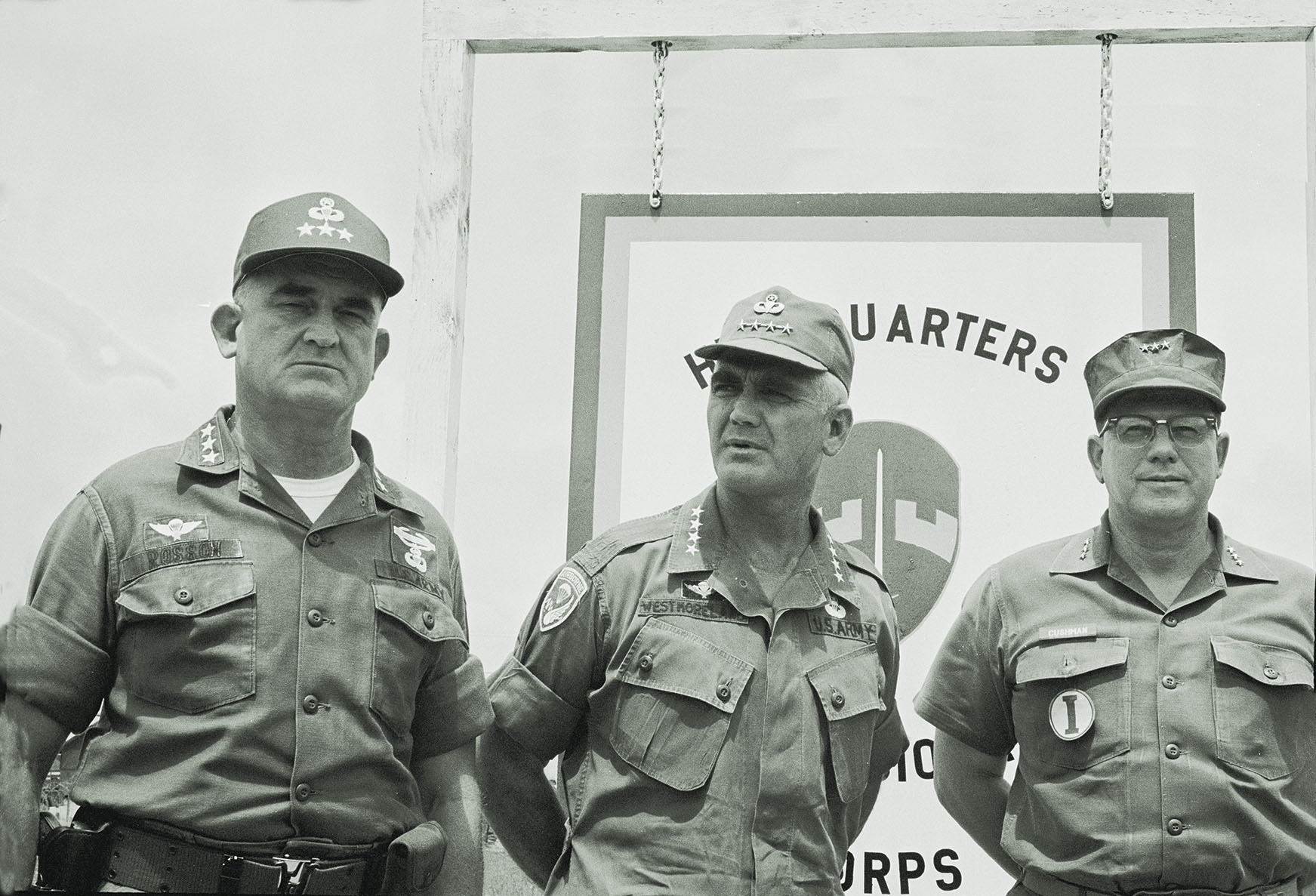

On March 10, Westmoreland formally created Provisional Corps Vietnam. PCV was led by Army Lt. Gen William B. Rosson, with Marine Maj. Gen. Raymond G. Davis as deputy. PCV was headquartered in the Hue-Phu Bai area, about 50 miles north of the III MAF headquarters at Da Nang. (On Aug. 15 PVC became XXIV Corps in a reactivation of a World War II unit.).

In addition to setting up a corps headquarters, the Army bolstered I Corps with two highly mobile elite divisions: the 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) and the 101st Airborne Division, which included the 3rd Brigade of the 82nd Airborne Division. They had been in the II Corps Tactical Zone, central South Vietnam.

On the organization chart, PCV was subordinate to the Marine headquarters, but the 1st Cav and 101st Airborne were not directly under the control of the III MAF commanding general, Cushman. They reported directly to Rosson. He even got operational control of the 3rd Marine Division, based at Dong Ha.

To many Marines, the establishment of the Army PCV headquarters seemed to be a vote of no confidence in III MAF—and to a large degree it was.

“General Cushman and his staff appeared complacent, seemingly reluctant to use the Army forces I had put at their disposal,” Westmoreland wrote after the war. “Marines are too base-bound.”

Maj. Gen. Rathvon McClure Tompkins, commander of the 3rd Marine Division, deeply resented the establishment of PCV. “It’s tantamount to…the relief of a commander,” he asserted. III MAF headquarters never completely trusted the arrangement.

Davis, however, was unconcerned. “I did not see having a senior Army command in the Marine zone as a vote of no confidence…vis-a-vis Marines at Da Nang [III MAF headquarters],” he recalled. “The Army had put its best and most important forces forward…these were the best the Army had, and they were in an all-helicopter posture…so I can see how the Army would be ticklish about turning them over to the Marines.”

I got to know Davis well. After serving as a captain in the 3rd Marine Division’s Lima Company, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marine Regiment, I was reassigned to the battalion staff and became Davis’ aide de camp. I spent a couple of years with him and spoke with him on an almost daily bases. I interviewed him for books I’ve written.

Army Lt. Gen. Richard Stilwell, who succeeded Rosson as head of PCV in July 1968, described Davis as “a pleasant, mild-mannered man in many respects, but was one of the most aggressive personalities I’ve ever encountered, a sort of bulldog determination.”

That aggressive determination was evident when the Army’s request for a Marine deputy to serve with Rosson reached Headquarters Marine Corps in Washington, where Davis was in charge of personnel. Visiting the commandant to recommend a general to fill the new position in I Corps, he said laconically: “I have someone in mind—me.” The commandant agreed, and Davis’ name was forwarded. Rosson enthusiastically accepted.

The discord in the upper ranks of the Army and Marines in I Corps spawned harsh words from both combatants.

“The Marines failed to provide adequate air support to 1st Cav Division units in I Corps,” Westmoreland complained at a meeting. Cushman objected, saying that the 1st Cav, “did not know how to ask for it and did not know how to use it.”

“I blew my top,” Westmoreland said in an interview after the war, adding that this was “absolutely the last straw.” He moved to centralize control of air operations under a single manager, the 7th Air Force—an anathema for the Marine Corps, which considered its aviation units to be an integral part of the Corps’ air-ground team.

The dispute intensified when Gen. William W. Momyer, commanding the 7th Air Force, called upon Rosson to get the Army general’s support for the concept. Rosson was aware of Marine sensitivity and, unknown to Momyer, invited Davis to sit in on the meeting. To say the Air Force officer was disconcerted to see the Marine general in the office would be an understatement.

On March 7, Westmoreland issued a directive implementing the single-manager concept.

Davis reported to PCV in March 1968 and was immediately welcomed by Rosson, who treated him as a fellow professional and a friend. Rosson made sure his staff and the other generals, including Maj. Gen. John J. “Jack” Tolson III of the 1st Cav, Maj. Gen. Olinto M. Barsanti of the 101st Airborne and Tompkins of the 3rd Marine Division, extended the same consideration.

Davis reciprocated and immediately began to develop not only professional working relationships with the Army generals but also personal friendships. He let it be known that he was there to learn. None of the fractious Marine vs. Army relationships so prevalent at the senior-command level existed on Rosson’s team.

I noted a marked difference between the two Army generals and the Marine division commander. Tolson and Barsanti were vibrant, enthusiastic troop leaders. Tompkins appeared to be worn out—the weight of command seemed to rest heavily on his shoulders. I believe he had been at war too long. The Marine had fought in World War II at Guadalcanal (where he earned a Bronze Star with a V device for valor), Tarawa (Silver Star) and Saipan (Navy Cross). In Korea, he received a second Bronze Star with a V.

Davis started a routine that became standard throughout his tour in Vietnam—up at dawn, a short situation briefing and then a visit to units in the field. Rosson provided Davis with a helicopter on a daily basis to visit the Corps’ area of operations. “It was an ideal way to get oriented and attuned to the entire situation in terms of evaluating the readiness and effectiveness of [our] forces,” Davis stated. He returned to PCV headquarters at Phu Bai late in the afternoon.

The Army commanders encouraged Davis to attend their briefings and participate in their operations. On one occasion, he observed the 1st Cav conduct a helicopter assault in the notorious A Shau Valley, a corridor used by the NVA to move supplies and personnel down the Ho Chi Minh Trail. It was also a staging area for attacks in northern I Corps.

The NVA had taken control of the A Shau Valley in March 1966 after overrunning an isolated Special Forces camp. The North Vietnamese fortified the valley with powerful 37 mm and rapid-firing twin-barreled 23 mm anti-aircraft guns, scores of 12.7 mm heavy machine guns, a warren of underground bunkers and even tanks.

The observations that Davis made during the 1st Cav operation would assist him when he commanded the 3rd Marine Division and sent the 9th Marine Regiment into the A Shau and Song Da Krong valleys. Army leader Stilwell called Davis’ operation, “a resounding success. … As an independent regimental operation … it may be unparalleled.”

Davis also observed an operation by the 2nd Brigade, 101st Airborne Division, in conjunction with the South Vietnamese 1st Division’s elite Black Panther Company. The Panthers trapped an NVA battalion near the small village of Phuc Yen, 2 miles northwest of Hue. U. S. Army helicopters rapidly transported the brigade to the fight and completed the encirclement, while allied artillery pounded the North Vietnamese for two days until the NVA force was destroyed. The final tally was 300 enemy dead and 100 prisoners taken, the largest number of captives during a single engagement up to that time.

In late April, the Marine Special Landing Force, Battalion Landing Team 2/4 (2nd Battalion, 4th Marine Regiment), engaged elements of the NVA’s 320th Division near Dai Do, just north of the 3rd Marine Division headquarters at Dong Ha. Rosson and Davis happened to be on a routine visit at the time. Tompkins briefed them on the division’s activities but barely mentioned Dai Do and did not seem particularly concerned about the action.

Rosson and Davis returned to Dong Ha the following day. As their helicopter approached the base, the two generals saw evidence of heavy fighting around Dai Do. Plumes of grayish smoke marked bomb and artillery strikes. Supply and medical evacuation helicopters busily scurried back and forth. It was obvious that 2/4 was in heavy combat with a major enemy force—yet Tompkins held back U.S. forces that could have been used to destroy the enemy. There were 15 combat battalions in the division’s area of operations, including a brigade of the 1st Cav.

Rosson “was disappointed with Tompkins,” Davis recalled. “I could feel he was concerned about the mobility of the Marines…and I agreed.” Rosson’s aide told me privately that the Army commander “was so upset with Tomkins that if he hadn’t been a Marine, he would have relieved him.” Rosson was concerned that an Army general firing a Marine general would have strained Army-Marine relationships even more.

The A Shau, Phuc Yen and Dai Do operations convinced Davis that the Marines had to revise their tactics and become more involved in high-mobility operations. “This was an entirely different concept [of operations], and I picked it up immediately,” he said. One PCV officer said senior officers on Rosson’s staff would “take turns having dinner with him [Davis] every night in the headquarters mess, giving him our ideas on mobile warfare, and during the day we flew around with him.”

Davis wrote an article that offered a hypothetical example of how a Marine regiment could conduct a heliborne assault and submitted it to the Marine Corps Gazette, a professional journal that serves as a forum to discuss issues and ideas. Davis’ article combined Army and Marine helicopter tactics into a lessons-learned format. A month after submitting the article, Davis received a rejection slip: “As the article did not contain anything new in the way of innovative tactics, the Gazette did not feel it was worthy of publication.” One rather terse comment simply stated: “Nothing new here, the Corps has been doing this for years.”

Davis, upset, called the Headquarters Marine Corps chief of staff to gain his support. The article was published. The incident was another example of the Marine Corps’ failure to understand the realities of the war in northern I Corps.

The Army viewed helicopters as Sky Cavalry, a means to outmaneuver and outflank the NVA, while the Marines still thought of their helicopters as boats designed to get troops from ships to shore to break through the enemies’ defensive positions.

The Marines seemed to have a defensive attitude about helicopters. I discovered that attitude when I observed the 1st Cav lift an entire battalion at one time. I remarked to a senior Marine officer that the air seemed to be full of helicopters. The officer puffed up and sneered. “Just remember, captain,” he said, with heavy emphasis on the word “captain,” “the Marines developed vertical assault. They [the Army] are just interlopers.” The Marines may have invented the troop-carrying helicopter, but they failed to exploit it fully as the Army had done.

At 11 a.m. on May 21, 1968, a small group of onlookers gathered around the 3rd Marine Division landing zone at Dong Ha as Davis took command of the division. Having observed the division for two months at PCV, he knew exactly what he wanted to do.

“I had enough time to do something I had never done before or since, and that is to move in prepared in the first hours to completely turn the command upside down,” Davis said.

Davis immediately assembled his key staff officers and regimental commanders and told them his yet-to-be-published article on heliborne assaults in the Marine Corps Gazette was to be used as a guide. After he departed, several of the more senior officers groused about the new precepts.

It did not take them long to understand that Davis meant exactly what he said. One day later, during the morning intelligence briefing, a South Vietnamese officer pointed to the location of two major North Vietnamese units on a map. Davis commenced a major operation using a multibattalion force, including two battalions quickly brought in by helicopter.

“Because of my close relationship with Bill Rosson, I had his promise of support,” Davis said. “He’d give me Army helicopters if necessary. … I was assured of support. Rosson [and his relief, Stilwell] guaranteed me that when we’d go into these tactical operations I never needed to look back over my shoulder a single time and wonder if I was going to be supported. I could get on the phone and they’d launch an Army brigade up there to help me if necessary. They would never leave me out on a limb.”

Davis had not received such assurances from III MAF and its 1st Marine Air Wing, which commanded helicopters and fighter-bombers. That lack of support was particularly galling, Davis said, because the 3rd Marine Division “established all kinds of records, in terms of helicopter lift, support and utilization rates—but something was wrong with the system. It led to too many bad days.”

Davis thought the allocation of Marine helicopters “was so centralized that you have got to work out in detail the day before exactly what you want and schedule it. There’s no way a ground commander can work out a precise plan for the next day’s operation unless the enemy is going to hold still.” Davis wanted a system “totally flexible and responsive to the ground commander’s needs.” On one particularly lamentable occasion, a flight of CH-53 Sea Stallion heavy-lift helicopters “ran out of flight time”—the number of hours the crew could fly before rest— in the middle of an operation and was ordered to return to base.

Brig. Gen. Earl E. Anderson, III MAF chief of staff, addressed Davis’ views in staff correspondence: “Ray Davis has really been shot in the fanny with the Army helicopter system, although I frankly believe that it’s more the result of the large numbers of helicopters available to the Army units, together with the fact that the ground officer has greater control over them than does the Marine commander.”

Davis fired back that this was exactly the problem. He complained that after the initial planning for an operation the Marine infantry commander played a secondary role: “The helicopter leader with his captive load of troops decides where, when and even if the troops will land.”

Cushman maintained Westmoreland “never could understand why the Marine Corps’ helicopters were not attached to the divisions and all this kind of Army doctrine, and I kept explaining why, but I never could convince him.”

A single Marine aviation unit, Marine Aircraft Group 39 at Quang Tri, supported the 3rd Marine Division. It was unable to provide enough support for Davis’ high-mobility concept. The MAG-39 commander, a colonel, did not have the clout to change rigid operational procedures in a fast-paced tactical situation. He once commandeered the helicopter regularly scheduled for Davis’ daily inspections and used it for his own purposes because he thought his position as group commander enabled him to use the chopper as he wanted. He did not view the division commander’s interests as important as his, which seemed to highlight the deteriorating relations between Marine air and ground officers.

In an attempt to placate Davis, the 1st Marine Air Wing, based at Da Nang, 70 miles south of the 3rd Marine Division headquarters at Dong Ha, established an auxiliary command post at Quang Tri under Brig. Gen. Homer S. Hill, an assistant wing commander. Hill helped Davis make the mobile concept work. “He was here to solve problems,” Davis said, and he “had enough authority delegated to him. He could order air units to do things.”

However, the air wing still complained that “Davis was totally insatiable.” Davis commented that he was “amused at my ‘insatiable’ need for choppers … when I had more enemy than anybody else!”

The Marine general bluntly told III MAF: “If I don’t get this helicopter support that I’m asking for from you, I’m going to get it from the Army. The devil take the hindmost.”

The success of Davis’ concept for mobile operations depended not only on the helicopter, but also on extensive exploitation of intelligence gathered by small reconnaissance patrols, supplemented by electronic and human-acquired intelligence, and supported by air and artillery forces.

“The division never launched an operation without acquiring clear definition of the targets and objectives through intelligence confirmed by recon patrols,” Davis said. “High mobility operations [were] too difficult and complex to come up empty or in disaster.”

The allocation of helicopters was never satisfactorily resolved. It remained a constant source of irritation during Davis’ assignment. In April 1969, Davis was ordered to the Marine Corps Development and Education Command as director of the Education Center at Marine Corps Base Quantico and promoted to lieutenant general. Upon the transfer, Cushman rated Davis’ performance as outstanding, except in the area of “cooperation.” I believe this mark was the result of Davis’ continued push for additional helicopter support.

On March 12, 1971, Davis received his fourth star and became assistant commandant of the Marine Corps. He retired one year later after 34 years of service. Davis died Sept. 3, 2003. V

Dick Camp retired from the Marine Corps in 1988 as a colonel after serving 26 years. Camp has written 15 books and more than 100 articles in military magazines. His most recent book is Three Marine War Hero: General Raymond G. Davis. Camp lives in Fredericksburg, Virginia.

This article appeared in the August 2021 issue of Vietnam magazine. For more stories from Vietnam magazine, subscribe here and visit us on Facebook: