Cold and calculating, brash and brutal, members of the local “home guard” depicted in Charles Frazier’s acclaimed Civil War novel Cold Mountain hunted down Southern deserters with zeal as fierce as their ulterior motives.

But whether home guards were as resolute in reality as in Frazier’s tale depended on what they believed their responsibilities really were, how seriously they took them and where they were operating.

Just who were these secondary soldiers who formed the home guards, and what were they supposed to be doing?

In the spring of 1861, just weeks before shots fired at Fort Sumter opened the war, Atlantic Monthly correspondent Phillip G. Hubert took a walking tour of Charleston. Brig. Gen. P.G.T. Beauregard was hard at work aiming batteries at the fort and teaching the South Carolina militia to use them. As the young militiamen trained to attack the enemy, older men organized themselves into a home guard to help defend the city if the enemy attacked first.

This may have been one of the first of the Civil War guard units, made up mostly of men too old or boys too young to fight as regulars, who were organized to keep the peace and serve as the last bastion of defense in towns and counties both North and South.

As the war progressed, the home guards played many roles—from policemen to cowboys—mostly of little consequence, usually with minimal training and equipment and almost always with minimal success. They were largely ignored by national and state governments, so there is only a scant record of their activity. In some instances they were used to guard bridges, rail lines and mail routes, or as scouts or escorts who knew the local terrain. Most of what is known about them comes from diaries, letters and press accounts. There is no accounting, official or otherwise, of how many guardsmen (and occasionally women) stood ready to defend the home turf, and it is probable that many of the volunteer units never had formal muster rolls. Louisiana historian John D. Winters estimates that 10,000 men and boys served in the state’s home guard over the length of the war, but whether that number could be duplicated across the Confederacy is hard to say.

The guard Hubert watched drill on Charleston’s Citadel Square appears to have been fairly typical. “About thirty troopers, all elderly men, and several with white hair and whiskers, uniformed in long overcoats of homespun gray,

went through some of the simpler cavalry evolutions,” he wrote. These men, according to Hubert, made up “a volunteer police force, raised because of the absence of so many of the young men of the city.”

These police forces apparently formed first in the South, as young men and plantation owners joined the Confederate cause in the heady days when everyone thought the war would be won in weeks. The home guard was meant as a stopgap, temporary force to keep things running back home for a short time. Home defense and police work were part of their duties, but in many parts of the South the job of watching plantations while slave owners were away was foremost.

In most places, the home guard was led by a captain and subordinate officers as in a regular military unit, and early in the war was often made up of young men who wanted to be ready to fight if they were called to regular duty. Historian Thomas Bahde points out in a study of Illinois home guardsmen that “especially in the early months of the war, when every local aspirant to martial glory was engaged in recruiting or drilling a company of volunteers, it could be hard to distinguish home guard companies from those being recruited for the federal service.”

In Illinois, at least, some men of fighting age were home guardsmen because they were “prevented from entering the federal service by family and economic obligations, as many owned significant personal wealth, headed large families, or figured prominently in the retail or public service sectors of their local economies,” Bahde wrote. “If home communities were to remain viable while their young men marched off to war, such men could ill afford to abandon their obligations.”

But once the able-bodied units were melded into the national armies, many of the troops left behind became little more than social clubs. Most were unpaid volunteers and even the best of them were usually ill prepared for any real fighting. Some guard units were rightly seen as a haven for men who had no intention of facing combat.

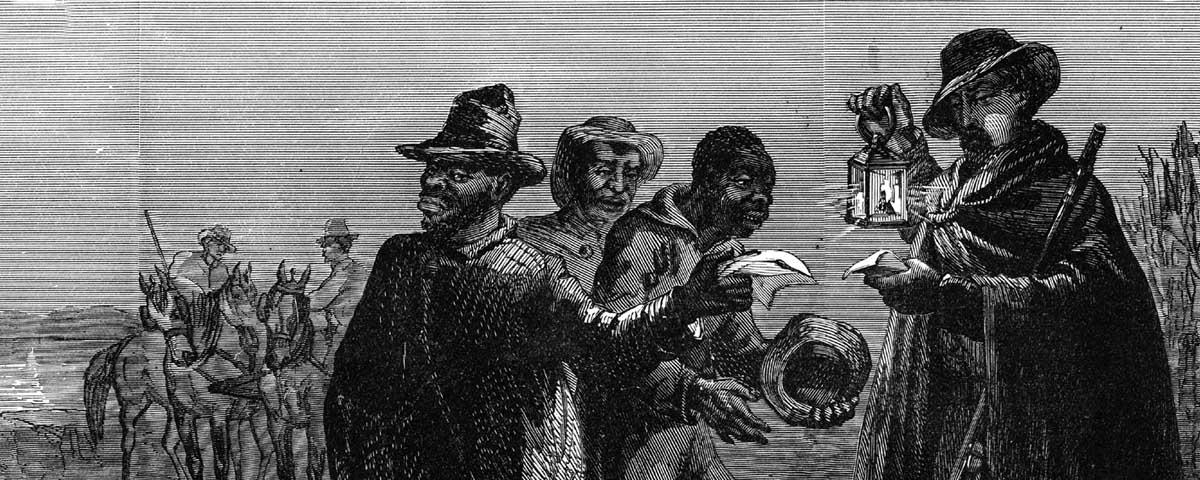

With passage of the Confederate conscription act in 1862 and the Northern draft laws a year later, the duty of finding deserters and draft dodgers often fell to home guard units, but their role as conscript hunters was not always played with the ruthless determination portrayed in Cold Mountain.

“For the first year or more after passage of the conscription act, the deserter had little to fear so long as he avoided public places,” North Carolinian David Dodge wrote in a reminiscence 30 years after the war’s end. “Now and then the [captain] of the home guard would call out such members of his command as could render no plausible excuse for not responding, and bluster through the neighborhood in a perfunctory kind of way. The deserter who was at home…feeding his stock, and living much the same life as usual, always had abundant warning to step out of sight until the motley array thundered by. An hour later he would be in his corn field again.”

A few home guard units did gain a measure of notoriety guarding prisoners of war. A deposition given by a Private Tracy of Company G, 82nd New York Volunteers, was printed in a November 1864 edition of The Soldier’s Journal, a newspaper distributed in Virginia, under the headline, “Rebel Cruelties to Prisoners.”

Tracy was captured with about 800 Federal troops near Petersburg, Va., on June 22, 1864, and was at first treated fairly. But after being marched to Richmond, he and other prisoners “came under the authority of the notorious and inhuman Major [Thomas P.] Turner [warden of Libby Prison in Richmond] and the equally notorious Home Guard. Our rations were a pint of beans, four ounces of bread and three ounces of meat a day. All blankets, haversacks, canteens, money, valuables of every kind, extra clothes, and in some cases the last shirt and drawers had previously been taken from us.”

At Lynchburg, Tracy and 1,600 prisoners were placed under another home guard unit “officered by Major and Captain Moffett.” The march from Lynchburg to Danville, Tracy said, “was a weary and painful one of five days under a torrid sun, many of us falling helplessly by the way and soon filling the empty wagons of our train. On the first day we received a little meat but [thereafter] the sum of our rations…was thirteen crackers.”

Changing roles of home guard units during the war brought considerable—and still unresolved—confusion over how these units were meant to be used and how well they did their duty; clearly some guardsmen took advantage of the confusion to take on more authority than was granted by law or military regulation, or was desired by their neighbors. But lack of direction also allowed some guard units to do practically nothing—which in at least one instance was sufficient.

Colonel August V. Kautz was in command of the 2nd Ohio Cavalry in the summer of 1863, when troops under Confederate General John Morgan made a daring, 1,000-mile raid through Tennessee, Kentucky, Indiana and into southern Ohio. Home guardsmen who just got in Morgan’s way helped to finally bring the raider to bay, he said, but Kautz gave the guard pretty low scores on any actual combat ability.

In a newspaper interview 20 years after the war, Kautz claimed “perhaps more than a hundred thousand” home guard troops turned out along Morgan’s route to repel “the audacious invader of Northern soil.” He said Union troops pursuing Morgan were aided by “the simple presence” of the home guard and other local organizations that harassed him throughout his march, “even when there was little effort or disposition to fight him.”

Other guard units also formed quickly in the face of a specific threat and were quickly disbanded when the threat was over. The home guard in Adair County, Mo., formed in August 1861 and guarded bridges there for only two months before being disbanded.

Diarist Will Duncan was 68 when he enlisted on July 1, 1863, in Company E of the 2nd Pennsylvania Militia. He was one of more than 1,100 men who turned out in response to a call for volunteers to help fend off Robert E. Lee’s invading army. But as pointed out by Robert P. Broadwater, who edited Sergeant Duncan’s diary, “As a short term militia unit that saw no real combat [the unit] had no regional histories written about it and, in fact, there is very little in the official record to even commemorate its existence.”

Duncan and his fellow volunteers served primarily as garrison troops to relieve more seasoned men for fighting off Lee’s incursion into Pennsylvania. If his life was typical, home guard duty was pretty humdrum stuff.

On July 25, 1863, he reported that a scouting party went out “and returned with a horse and two chickens.” On July 29 his diary tells us he gathered a lot of blackberries and “had a nice supper consisting of blackberries and hard tack.” On August 15 a fellow guardsman went to town, got drunk and “came part of the way home and then lay down and was unable to go further.”

That seemed to be unexceptional. A number of Duncan’s diary entries record “a great many of the boys got drunk today,” or something similar. His diary begins July 24, 1863, and ends November 27. The nearest thing to combat recorded are several instances of picket duty, during one of which he shot a good bag of ducks and geese.

Not all guard units were composed of old white geezers. Volunteer regiments from the Five Civilized Tribes of the Indian Territory (Oklahoma today) organized themselves into infantry regiments that were called home guards but actually fought with Union forces in Kansas, Missouri and Arkansas. Its members were primarily from the Cherokee, Creek and Seminole nations.

The 1st Regiment, organized in LeRoy, Kan., on May 22, 1862, was made up of 66 officers and 1,800 enlisted men, and composed mainly of Creek Indians along with some Seminoles and blacks. The 2nd Regiment included 52 officers and 1,437 enlisted men. It was formed in southern Kansas and in the Cherokee Nation some time between late June and early July 1862. The 3rd Regiment was formed at Tahlequah and Park Hill, Indian Territory, in July 1862. Its ranks included some former Confederate soldiers. Between 1862 and 1865 these regiments participated in a number of skirmishes and fought in the battles of Prairie Grove, Ark., and Honey Springs, Indian Territory, which was an important victory for Union forces trying to control the area.

Historian Arthur Bergeron Jr. found two gens de couleur libres (free men of color) in Company I of the 2nd Louisiana Reserve Corps, formed in 1864. The men were from St. Landry Parish, where freedmen who sometimes had extensive land holdings and were slave owners themselves often sympathized with the Confederate cause. Bergeron, however, speculates that there may have been another reason for their enlistment late in the war.

“These men found themselves faced with a choice in the late summer or early fall of 1864—they could enlist in combat units or wait for conscription as laborers….To avoid the degrading conditions and work of the labor camps, where they would find the same treatment given the slaves around them, these men chose an action that would emphasize their distinctiveness from other blacks.”

The corps saw hardly any fighting but was used to track down criminals, deserters and draft evaders. The 2nd Louisiana Reserve, formed largely of men from the cattle-rich prairies of southwest Louisiana, was also sometimes used to round up cattle to feed the Confederate army.

A considerable number of home guard units devolved into nothing more than a group of men assembling from time to time to drill or do token duty, carrying their own shotguns, rifles or pitchforks, and dressed in makeshift uniforms that varied not only from unit to unit, but from person to person. The New York Daily Tribune carried a report in August 1861 from Jefferson City, Mo., about Colonel Joseph McClurg’s regiment of home guards “composed of men who have left the plow and the ax at the call of their country.” The newspaper reported they lacked arms, and that “visiting their camp, any day, you may see them lying upon the ground in the shade, or mounted upon gaunt horses, scouring the country, arrayed in homespun garments.”

The Crawford County, Ark., local militia conducted its annual muster and drill on February 23, 1861, in the town of Van Buren and got a less than glowing review by the Van Buren Press, which reported, “A more decided burlesque on military parade could not be had than the muster on Saturday. If any good was derived by bringing such a body of men together for ‘inspection’ and ‘drill,’ we were not able to discover it—and we trust it will be at least another year before another ‘occasion’ occurs for preparation to defend our rights and liberties against northern aggression.”

In New Orleans the guard appeared to be better dressed—if not well equipped—and made up of businessmen who gave time and treasure to the Confederate cause. Writer George W. Cable, who was a young boy at the time of the war, provided a reminiscence of a city that most able-bodied men had left to fight elsewhere. Each afternoon, he said, he and other boys could be found in Coliseum Place in the center of the city, “standing or lying on the grass watching the dress parade of the Confederate Guards. Most of us had fathers or uncles in the long, spotless, gray, white-gloved ranks that stretched in such faultless alignment down the hard, harsh turf of our old ball-ground. This was the flower of the home guard. The merchants, bankers, underwriters, judges, real-estate owners, and capitalists of the Anglo-American part of the city were all present or accounted for in that long line. Gray heads, hoar heads, high heads, bald heads. Hands flashed to breast and waist with a martinet’s precision at the command of Present arms, hands that had ruled by the pen and the dollar since long before any of us young spectators was born, and had done no harder muscular work than carve roasts and turkeys these twenty, thirty, forty years. Here and there among them were individuals who, unaided, had clothed and armed companies, squadrons, battalions, and sent them to the Cumberland and the Potomac. A good three-fourths of them had sons on distant battlefields, some living, some dead. We boys saw nothing pathetic in this array of old men….Merely as a gendarmerie they relieve…many Confederate soldiers of police duty in a city under martial law, and enabled them to man forts and breastworks.”

By 1864, when the Union Army occupied much of the Confederacy, many home guard units disbanded to avoid being mistaken for guerrillas. By the war’s end, few Southern home guards still existed. Those still together may have caused more havoc than they remedied. Sara Matthews Handy described in 1901 an incident that occurred as Union soldiers approached her home in Cumberland County, Va., during the last days of the war.

“The Home Guard, a militia composed of old men and boys, with the aid of a small detachment of regular soldiers, were…detailed to break open the liquor stores in the city and empty the liquor into the gutters, in order to mitigate as far as possible the horrors of the expected sack. The work was begun according to the programme, but…[then] out from every slum and alley poured the scum of the city, fugitives from justice, deserters, etc. The troops were knocked down over the barrels they were striving to empty, and a free fight ensued. Men, women, and children threw themselves flat on the pavement and lapped the liquor from the gutters; or, seizing axes, broke into any and every store they chose….Fire caught the inflammable fluids and ran in a stream of flame along the streets. The firemen abandoned their hose and joined the mob in the work of wholesale plunder; and riot and robbery held high carnival, while the flames raged without let or hindrance, until the morning, when the Union army entered quietly and decorously, and at once set to work to extinguish the conflagration, thus presenting the spectacle, unique in history, of a besieging army occupying a town, and, instead of harrowing the residents, at once proceeding to relieve their suffering from fire and famine.”

Jim Bradshaw, a retired newspaper editor and columnist who lives in the historic town of Washington, La., has written three books on the history and culture of south Louisiana.