The colonel thought his men had lost it. There they were, in God-Knows-Where, Belgium, under heavy fire from German 88s. There was no noise like ack-ack fire: the whistle, the shell burst, and now the tense silence between rounds. And yet these men were laughing, which, in a way, was more terrible even than the gunfire. This is it, he thought, they’ve cracked. It’s too much for them. But as the colonel drew nearer to the gun pit and the report of the shells faded, he could hear the men’s laughter more clearly. It was a warm, relaxed sound—almost merry—inspired not by the trauma of combat but by a copy of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the coming-of-age novel by Betty Smith, which one soldier was reading aloud between blasts.

The colonel thought his men had lost it. There they were, in God-Knows-Where, Belgium, under heavy fire from German 88s. There was no noise like ack-ack fire: the whistle, the shell burst, and now the tense silence between rounds. And yet these men were laughing, which, in a way, was more terrible even than the gunfire. This is it, he thought, they’ve cracked. It’s too much for them. But as the colonel drew nearer to the gun pit and the report of the shells faded, he could hear the men’s laughter more clearly. It was a warm, relaxed sound—almost merry—inspired not by the trauma of combat but by a copy of A Tree Grows in Brooklyn, the coming-of-age novel by Betty Smith, which one soldier was reading aloud between blasts.

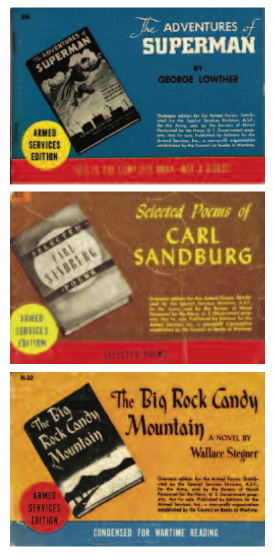

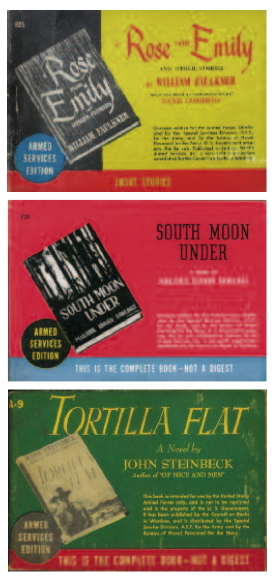

An antiaircraft gun pit may seem like an unlikely place for a paperback, but between 1943 and 1947, a series of pocket-sized books called Armed Services Editions were considered as essential to morale as cigarettes and candy. Manufactured for and distributed to American servicemen exclusively, Armed Services Editions gave soldiers from Normandy to Burma the opportunity to read as they had never read before. The program, a collaboration between the U.S. Army and a council of publishing executives, was described in 1945 by the Saturday Evening Post as “the greatest book-publishing project in history.” And indeed, Armed Services Editions did shape—and, in some cases, create—the reading habits of an entire generation. But the purpose of the little books went beyond mere recreation; they also stood as a symbol of what the Allied forces were fighting for. As Roosevelt wrote in 1942, “A war of ideas can no more be won without books than a naval war can be won without ships.”

The concept of issuing pocket-sized books to the military didn’t come to the government immediately, nor was the idea of sending books to those overseas new. Book drives for the military had occurred regularly at libraries across the country during World War I. But after the outbreak of World War II, Americans began raiding their personal libraries for books to send to troops overseas with a vigor that far outstripped their previous efforts—motivated this time by nearly a decade of exposure to news stories about Nazi book bans and photographs of towering infernos built to consume “un-German” tomes. The first Nazi book burnings, organized across 34 college towns by the German Students Association on May 10, 1933, reduced some 25,000 books to ash; by 1938, the Nazi government had outright banned 18 categories of books—4,175 titles in all—and the works of 565 authors, many of them Jewish. Now that the United States was officially at war, what better way to strike back at the enemy than by allowing soldiers to read exactly what they wished? Books were no longer simple diversions for fighting men—they had become totems signifying what those men were fighting for.

As a result, the donation campaigns—such as the Victory Book Campaign, organized by the American Library Association to benefit the army and merchant marine—were wildly successful. Civilians contributed books of every genre, shape, and size; by January 1942, 25,000 books had been donated in New York City alone. But, as Lieutenant Colonel Ray L. Trautman, head of the Army Library Service, found, the efficient delivery of those volumes across the globe was another challenge entirely. The mishmash of books was difficult to sort, and cumbersome to package and transport. And because getting food, weapons, and medical supplies to the front was paramount, the reading material was often tossed aside—sometimes literally. In one instance, 400,000 paperbacks and 100,000 hardbacks intended for North Africa were abandoned because the commander of the naval convoy assigned to deliver them had determined they weren’t a priority. Trautman tried a “book kit” program, shipping crates of reference books, paperbacks, and hardbacks to camps overseas, but the same issues surfaced. Trautman was at a loss. He needed books that were light, uniformly sized, and portable—books that, ideally, would cater to every taste: mysteries, westerns, bestsellers. They didn’t exist; he would have to create them. But how?

It was H. Stahley Thompson, a graphic artist working in the army’s Special Services Division, who proposed printing paperback books on the rotary presses typically used to produce magazines. Titles could be printed two at a time on the large, whisper-thin paper; a horizontal cut would separate the pages into two small books. Once the cut was made and the spine stapled, each finished book would be just the right size to slip into a fatigues pocket. It was an artist’s solution—elegant, simple. But best of all, it was practical: each book cost only six cents to manufacture.

It was H. Stahley Thompson, a graphic artist working in the army’s Special Services Division, who proposed printing paperback books on the rotary presses typically used to produce magazines. Titles could be printed two at a time on the large, whisper-thin paper; a horizontal cut would separate the pages into two small books. Once the cut was made and the spine stapled, each finished book would be just the right size to slip into a fatigues pocket. It was an artist’s solution—elegant, simple. But best of all, it was practical: each book cost only six cents to manufacture.

The army would have to obtain permission to print the books, so the support of the publishing industry was vital. In January 1943, Trautman and Thompson presented their plan to Malcolm Johnson, a top editor at the publisher D. Van Nostrand. Johnson was on the executive committee of the Council on Books in Wartime, a group of publishers, librarians, and booksellers who had banded together in 1942 to figure out how to put their passion to work for the war effort. The council had good intentions and a terrific slogan—“Books are weapons in the war of ideas”—but limited reach, having served only in an advisory capacity to the Office of War Information. The plan to create custom paperbacks for the men overseas was a perfect marriage of the military’s needs and the council’s desires.

The commercial advantage of participating in such a program wasn’t lost on the council, either: they jumped at the opportunity to create demand for the commodity they produced. William Warder Norton, the founder of W. W. Norton Co., captured the full range of the council’s enthusiasm for the project when he wrote, “The very fact that millions of men will have an opportunity to learn what a book is and what it can mean is likely now and in post-war years to exert a tremendous influence on the post-war course of the industry.”

The council took over the printing end of the program completely, incorporating a nonprofit organization called Armed Services Editions, Inc. Trautman, his navy counterpart Isabel DuBois, and a small committee of publishing luminaries selected the titles. Trautman lobbied for popular hits—mysteries and westerns—while the industry pros pushed for more literary books such as Moby-Dick and I, Claudius. DuBois fell in between, but all were asked to avoid choosing books that might have an adverse effect on soldiers’ morale. The council decided on 30 titles for the initial set, or “A” series; it began with Leo Rosten’s The Education of Hyman Kaplan (A-1), a collection of funny stories, and ended with Jack Goodman’s The Fireside Book of Dog Stories (A-30). The books were packed into wooden cases, each with a capacity of 20 sets, and shipped as freight. On September 28, 1943, the New York Times reported that the first batch of 1.5 million Armed Services Editions had been delivered to the army and navy.

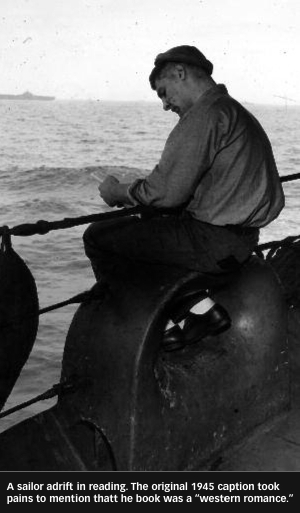

.jpg) They were, as one GI told reporter David G. Wittels of the Saturday Evening Post, “as popular as pin-up girls.” In the Philippine jungles, on the Anzio beachhead, in the English countryside, soldiers lined up for the opportunity to fight boredom with a book. The pocket-sized paperbacks were so coveted that men would often tear the flimsy books in two, allowing one to start a story while the other finished. Wittels suggests that the most popular titles were those that carried a hint of raciness—he cites The Star Spangled Virgin, Is Sex Necessary?, and The Lively Lady as examples, though a soldier would be hard-pressed to find the sort of satisfaction he was looking for in those stories. Anecdotal evidence, however, indicates that the books most favored by military men echoed the tastes of friends and loved ones back home.

They were, as one GI told reporter David G. Wittels of the Saturday Evening Post, “as popular as pin-up girls.” In the Philippine jungles, on the Anzio beachhead, in the English countryside, soldiers lined up for the opportunity to fight boredom with a book. The pocket-sized paperbacks were so coveted that men would often tear the flimsy books in two, allowing one to start a story while the other finished. Wittels suggests that the most popular titles were those that carried a hint of raciness—he cites The Star Spangled Virgin, Is Sex Necessary?, and The Lively Lady as examples, though a soldier would be hard-pressed to find the sort of satisfaction he was looking for in those stories. Anecdotal evidence, however, indicates that the books most favored by military men echoed the tastes of friends and loved ones back home.

Perhaps for this reason, Betty Smith’s A Tree Grows in Brooklyn (a bestseller on the home front) was a runaway hit among servicemen; demand for “that Brooklyn tree” was so high that a second edition was issued in July 1944, a first for the project. Smith estimated that she received four letters a day from servicemen, who thanked her for reminding them of home and told her that her book served as a powerful reminder of why they were fighting—and, in one instance, as the impetus. “One letter tells of 200 men on the waiting list for the book,” Smith wrote to her editor on May 5, 1944. “Another on a transport ship says the librarian showed favoritism in handing out the few copies and that the soldiers complained to the chaplain who brought about fair play.”

Contemporary writers were generally thrilled to be connected to the project. David Ewen, the author of the nonfiction titles Men of Popular Music and The Story of George Gershwin, was actually serving in the armed forces at the time his books were chosen for the project, so he was all too familiar with the long, idle hours before and after combat, and how the pleasure of reading could fill them. For Willa Cather, the Nebraska writer whose O Pioneers!, My Antonia, and Death for the Archbishop all shrank to pocket size, allowing her novels to be reprinted for servicemen gave her a sense of purpose at a time when Cather felt overwhelmingly dismayed by the Nazis’ progress in Europe. As Armed Services Editions, her novels reached men far outside her typical audience, like Corporal Erwin Rorick, on Leyte, who admitted that he had chosen to read Death for the Archbishop “under the delusion that it was a murder mystery, but he discovered, to his amazement, that he liked it anyway.”

The books were natural companions for men with much on their minds and little to do. “The days when no mail is received are not so lonesome when there is an unfinished story around,” a corporal stationed in New Guinea wrote to the Council on Books in Wartime. “Then, too, reading takes the mind away from the experiences we have that are so different from the environment we left and keeps you from concentrating on all the discomforts we have, always looking for things that annoy you, and becoming a slave to self pity.” Recognizing the books’ morale-boosting powers, officers encouraged their men to read, so long as the activity did not interfere with alertness or duty. In one instance, the lieutenant of a platoon of combat engineers valued the group’s small trove of Armed Services Editions so highly that he “refused to let any man have a book unless he would agree to read it aloud to the fellows in his shack or tent.”

The books were natural companions for men with much on their minds and little to do. “The days when no mail is received are not so lonesome when there is an unfinished story around,” a corporal stationed in New Guinea wrote to the Council on Books in Wartime. “Then, too, reading takes the mind away from the experiences we have that are so different from the environment we left and keeps you from concentrating on all the discomforts we have, always looking for things that annoy you, and becoming a slave to self pity.” Recognizing the books’ morale-boosting powers, officers encouraged their men to read, so long as the activity did not interfere with alertness or duty. In one instance, the lieutenant of a platoon of combat engineers valued the group’s small trove of Armed Services Editions so highly that he “refused to let any man have a book unless he would agree to read it aloud to the fellows in his shack or tent.”

The Special Services Divison made a particular effort to distribute books to those whose spirits most needed a lift, or who were about to embark on a particularly tough mission. The books were especially valued on troop transports, where men used them to pass the long, hot hours. In his essay “Cross-Channel Trip,” war correspondent A. J. Liebling describes the soldiers who are about to embark on Operation Overlord, “spread all over the LCIL [landing craft, industry, large] next door, most of them reading paper-cover, armed-services editions of books. They were just going on one more trip, and they didn’t seem excited about it.” An infantryman from Brooklyn, reading Candide, tells him, “These little books are a great thing. They take you away.”

The “little books” had a tremendous impact, proving so popular that Armed Services Editions, Inc., continued printing them through 1947. In the end, the number of volumes printed totaled almost 123 million, with 1,322 individual titles in the series. The total cost to the government? Less than eight million dollars. But the true reach of the program did not become evident until well after the war had ended. As W. W. Norton and his colleagues at the Council on Books in Wartime had hoped, the Armed Services Editions helped create a generation of men accustomed to having a book perpetually at hand. As a result, the book industry boomed in the late 1940s and through the 1950s, particularly sales of paperbacks, which before the war had been largely experimental and associated with lurid or low-quality writing. Many of today’s most familiar publishing imprints—Dell, Ballantine, Penguin—made their names by capitalizing on the sudden demand for inexpensive, freely available paper-cover books. As for the books that first inspired veterans to read, the majority were read to shreds during the war. The handful that did survive entered the civilian market, but as collectibles.

Armed Services Editions also influenced postwar career paths and even American literary tastes. Of the eight million veterans who furthered their education under the so-called GI Bill of 1947, at least a few were inspired to do so after picking up one of the little books. Helen MacInnes, author of the novel While We Still Live, remembered a letter she had received from a serviceman who “said he had read little until [the Armed Services Edition of her book] got him enjoying literature.” After his service, the soldier went to college, earned his Ph.D., and sent MacInnes a copy of his dissertation. “It was dedicated to me,” MacInnes recalled, “the writer of the novel that started his reading.” A veteran who became a professor at the University of Washington after the war said that the paperbacks, some of which he still owned, represented “the most positive of my memories of service days.” And Professor Matthew J. Bruccoli, an Armed Services Editions collector and F. Scott Fitzgerald scholar, suggests the military print runs of The Great Gatsby and The Diamond as Big as the Ritz may have a connection to the revival of critical interest in Fitzgerald’s work that began in the late 1940s. Even Ray Trautman, who had championed the addition of less literary tomes to the list of Armed Services Editions, observed, “The Army has discovered that there is as great a market for good books as for light stuff and trash. Veterans of World War II will have been accustomed to the best books.”

Armed Services Editions also influenced postwar career paths and even American literary tastes. Of the eight million veterans who furthered their education under the so-called GI Bill of 1947, at least a few were inspired to do so after picking up one of the little books. Helen MacInnes, author of the novel While We Still Live, remembered a letter she had received from a serviceman who “said he had read little until [the Armed Services Edition of her book] got him enjoying literature.” After his service, the soldier went to college, earned his Ph.D., and sent MacInnes a copy of his dissertation. “It was dedicated to me,” MacInnes recalled, “the writer of the novel that started his reading.” A veteran who became a professor at the University of Washington after the war said that the paperbacks, some of which he still owned, represented “the most positive of my memories of service days.” And Professor Matthew J. Bruccoli, an Armed Services Editions collector and F. Scott Fitzgerald scholar, suggests the military print runs of The Great Gatsby and The Diamond as Big as the Ritz may have a connection to the revival of critical interest in Fitzgerald’s work that began in the late 1940s. Even Ray Trautman, who had championed the addition of less literary tomes to the list of Armed Services Editions, observed, “The Army has discovered that there is as great a market for good books as for light stuff and trash. Veterans of World War II will have been accustomed to the best books.”

In the end, though, it didn’t matter whether the men who served read David Copperfield, U.S. Foreign Policy, or The Adventures of Superman. The value of the Armed Services Editions lies in the fact that they were books, and they did what books do best: offered companionship for those who were sad or lonely, provided escape when escape was sorely needed, and reminded their readers of a free world that was worth fighting for.

Caitlin Newman is an editor and writer living in Charlottesville, Virginia. She currently works on EncyclopediaVirginia.org, a digital reference about the people, culture, and history of Virginia, for the Virginia Foundation for the Humanities. Her favorite Armed Services Editions book is number 909—Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein.