It has become commonplace that current political and cultural fissures rival those at any other point in U.S. history. The Civil War is frequently offered as a comparative example to highlight contemporary disagreements. A New York Times piece from December 2021, titled “We’re Edging Closer to Civil War,” reflected this phenomenon in sketching an ominous national mood. Whether stemming from genuine ignorance about American history or from a cynical attempt to abet partisan political agendas, such claims and comparisons distort both mid-19th-century and 21st-century disruptions and, by extension, threats to the stability of the nation. In fact, as the United States enters the third decade of the 21st century, it is not witnessing an almost unprecedented breakdown of national civility. Public acrimony of the past decade pales in comparison to that of the period that included systemic political failure climaxing in secession, a cataclysmic military conflict, and wrenching postwar aftershocks that lingered for more than a decade.

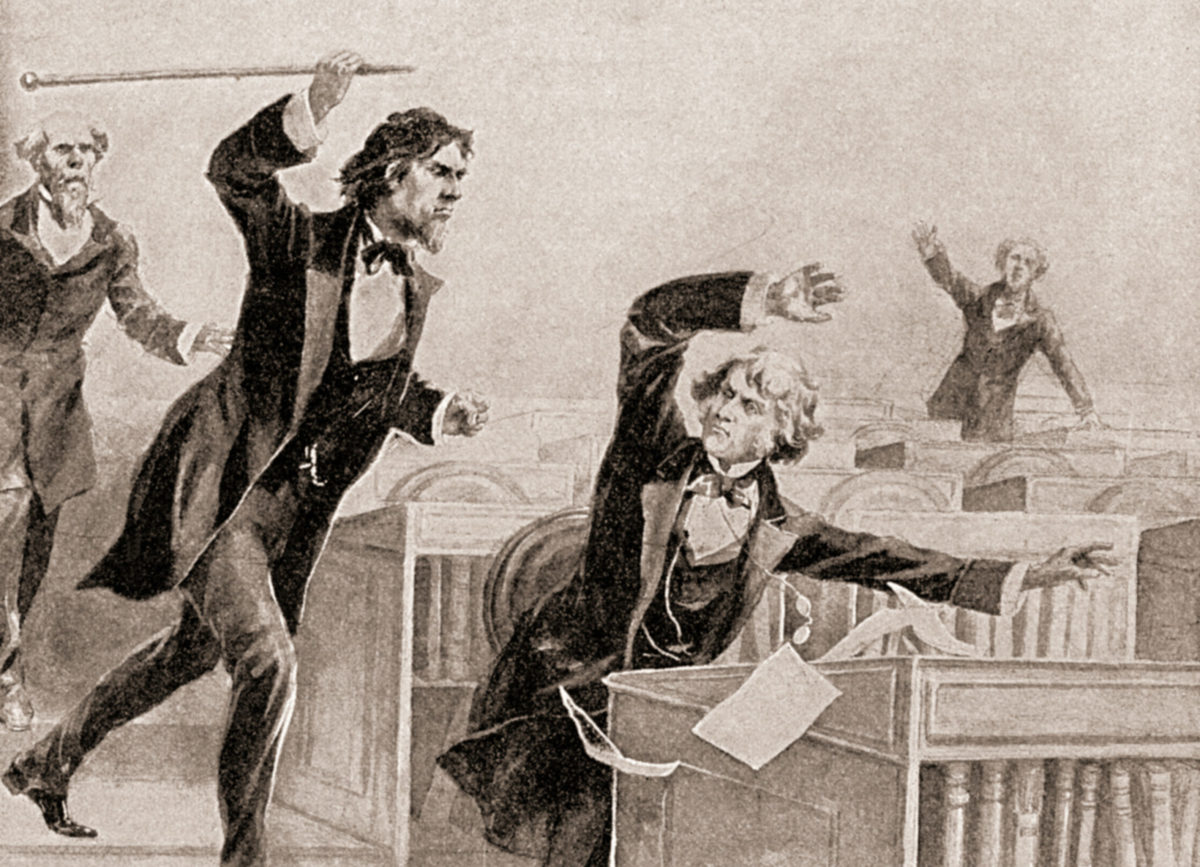

A few examples will illustrate the profound difference between the Civil War era and the recent past. Prominent actors increasingly use awards ceremonies as a platform to express unhappiness with political leaders. On April 14, 1865, a member of the most celebrated family of thespians in the United States expressed his unhappiness with Abraham Lincoln by shooting him in the back of the head. Similarly, Americans regularly hear and watch members of Congress direct rhetorical barbs at one another during hearings and in other venues. On May 22, 1856, Congressman Preston Brooks of South Carolina caned Senator Charles Sumner of Massachusetts into bloody insensibility on the floor of the Senate chamber because Sumner had criticized Senator Andrew Butler, one of Brooks’ kinsmen, for embracing “the harlot, Slavery” as his “mistress.”

Recent presidential elections have provoked a good deal of posturing about how Texas or California might break away from the rest of the nation. The election of a Republican president in 1860 prompted seven slaveholding states actually to secede between December 20 and February 1, 1861. Four of the remaining eight slaveholding states followed suit between April and June 1861, and Americans grappled with the reality that the political system established by the founding generation had failed to manage internal tensions during an election no one claimed had been tainted by fraud.

Events on January 6, 2021, at the Capitol in Washington, D.C., provide a final example. Often described by politicians and pundits, and even by some historians, as the gravest threat to the republic since the Civil War, the chaotic occupation of parts of the Capitol Building yielded deeply troubling images. But the incident lasted only a few hours before order was restored. The heated presidential canvass of 1860, in contrast, positioned the United States and the newly proclaimed Confederacy to engage in open warfare that stretched across four agonizing years of escalating bloodshed. More than 3,000,000 men eventually took up arms (that would be equivalent to more than 30,000,000 today). Between 618,000 and 750,000 perished (imagine between 6.2 and 7.5 million dead today). Hundreds of thousands of African American and White civilians became refugees (the number would be millions today). Four million enslaved people emerged from what Frederick Douglass called the “hell-black system of human bondage.” And the country soon entered a decade of virulent, and often violent, disagreement about how best to order a biracial society in the absence of slavery.

The key to mid-19th century political and cultural turmoil, and eventually to slaughter on battlefields, lay in the existence of the institution of slavery. Slavery’s toxic presence provoked debates about the gag rule in the House of Representatives, halted the untrammeled dissemination of printed materials to parts of the nation, affected diplomatic decisions relating to Mexico and Cuba, split mainstream Protestant denominations, hastened the breakdown of the second party system, and, in the late 1850s, triggered a low-level guerrilla war in “Bleeding Kansas” and John Brown’s quixotic raid on Harpers Ferry. The key issue centered on whether slavery would be allowed to expand into federal territories, creating a series of crises between 1820 and 1860 that ultimately proved intractable.

No political issue in 2022 approaches slavery in terms of potential explosiveness, which bodes well for the long-term stability of the republic. More broadly, to compare anything that has transpired in the past few years to the political, military, and social upheavals of the mid-19th century represents a spectacular lack of understanding about American history that is potentially destructive to current political discourse.

Public ignorance about U.S. history, or its willful manipulation for political ends, often gets in the way of fruitful debate about issues of surpassing importance that have ties to American past. The discussion of immigration, for example, too often betrays little appreciation of comparable public debates throughout U.S. history—or of the vitriol characteristic of some of those debates that makes the current ones seem almost tame.

Once again, the Civil War era provides useful context. The Know Nothings of the mid-1850s (formally the American Party), with a strong focus on nativist issues, won control of the Massachusetts Legislature, polled 40 percent of the votes in Pennsylvania in 1854, and significantly affected politics in numerous other states. Moreover, mid-19th century statistics attest to the fact that percentages of foreign-born residents currently are not at unprecedented levels. In 1861, as the Lincoln administration prepared to go to war to restore the Union, almost one-third of the military-age White males in the loyal states had been born outside the United States, and the proportion of foreign-born residents in 1860 and in 2020 was almost the same (the 1860 percentage rose in the censuses of 1870, 1890, and 1910).

A careful examination of U.S. history leads to an inescapable conclusion: A more certain sense of their national past would allow Americans, as a people, to know that almost no issue or debate is new, that earlier generations overcame far greater problems than the present generation faces, and that the nation almost certainly will emerge from current controversies intact.