‘Seldom did Apaches leave survivors when ambushing small parties. In this case, a teamster and three soldiers did cheat death, because the Apaches were focused on carving up a dead mule, torturing a survivor and making off with the other three mules’

As many as 100 Apaches lay in wait that warm March day in 1866 as a four-mule Army wagon rolled ever closer to Cottonwood Wash, 25 miles east of present-day Florence, Arizona. In the preceding few weeks, several large units had traveled this military road to Fort Grant, built the previous year at the confluence of Aravaipa Creek and the San Pedro River. All those bluecoats had made the Apaches wary, but on this day a scout brought them good news: The wagon held just nine soldiers and a teamster, with no other troops in sight. At the spot the Indians chose, ridges bordered the wash, closing to within about 220 feet of each other and terminating in rock outcrops 40 to 50 feet high. The numbers, terrain and time were ripe for an Apache ambush.

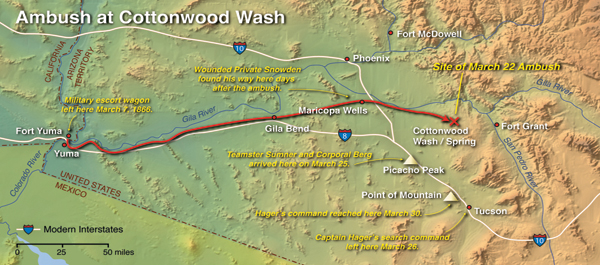

The Army was intent on stopping Apache harassment of settlers in Arizona Territory, something it had been unable to do during the recent Civil War. It sent companies of the 14th Infantry to Fort Grant (aka Camp Grant or Old Camp Grant) and other military posts in the territory. Soldiers typically traversed this hostile region in large groups, but today was different. The lone wagon was a military escort. Two officers—Captain/Brevet Major James Franklin (“Frank”) Millar of Company C, 3rd Battalion, 14th Infantry, and Assistant Surgeon Benjamin Tappan Jr., attached to the 7th Infantry, California Volunteers—were making the 250-mile eastward trek across the desert from Fort Yuma (on the California side of the Colorado River, opposite Yuma, Ariz.) to Fort Grant. Millar had been stranded in Oregon by bad weather during a leave of absence, and he was eager to rejoin his troops at Fort Grant. He had arrived at Fort Yuma about the time Tappan, who was stationed there, received orders to assume duties at Fort Grant. It made sense that the two officers should ride together under escort to their common destination. The wagon left Fort Yuma (“Hell’s Outpost,” the soldiers called it) on March 7. On March 22, Millar, Tappan and the other men were likely pleased when their bumpy ride smoothed out as the wagon reached the sandy bottom of Cottonwood Wash, less than 30 miles from Fort Grant. There was nothing in sight to alarm them.

The Apache leader and some warriors lay hidden on the north outcrop; others crouched behind rocks on the south outcrop. Below in the wash, an arroyo crossed the road and then skirted its north bank, concealed by bushes from the road. Many warriors lurked behind those bushes. Still others waited in an eroded hollow at the base of the south outcrop. The Apaches had centuries of experience at ambushing foes.

At a covert signal by the leader, the warriors opened fire from the outcrops and swarmed from behind rocks and bushes. Bullets and steel-tipped arrows rained down on the wagon, and some found their mark. Millar and Tappan were among the first casualties. For one of the two, the nightmare in the desert was only just beginning.

Twenty-five-year-old Tappan was from Ohio, while Millar, seven years older, hailed from Oregon, so it is unlikely they had crossed paths before their March meeting at Fort Yuma. They soon discovered, however, that their families had previous connections in Steubenville, Ohio. Tappan, nephew of Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton, came from a prominent Steubenville family that included a U.S. senator and a well-known physician. Millar’s father was a Presbyterian missionary who had taught school in Steubenville, and Frank’s sister Elizabeth later noted in her memoirs that their father was an “old friend” of Tappan’s father.

The captain and the assistant surgeon had a couple of weeks on that wagon to get acquainted before disaster struck that Thursday, March 22, but there would be no opportunity to cement a lasting friendship. Two of the opening shots in the ambush found Millar, and he slumped over dead. Tappan was hit three times, once in the leg and twice in the body, but he remained alive. Apache bullets also took a toll on the escort party, killing Private Charles Richards and gravely wounding Private John Powell. Teamster Stevens Sumner frantically turned the wagon around, even though he was hit by several arrows and one of the mules was shot dead. Another arrow pierced the back of Private Andrew Snowden’s head.

The survivors had no time to organize a defense. They scrambled from the wagon and ran for cover as best they could. Powell made it 60 feet before tumbling to the ground. The others scrambled into a drainage on the south side of the wash and followed it toward the ridgetop. The going was slow, especially for teamster Sumner and Corporal John Berg, both of whom were helping the wounded Tappan. A Private Donnell bravely dropped behind to provide covering fire, armed only with a muzzleloading rifle; for each shot, he had to tear open a paper cartridge, pour powder into the barrel, ram in a ball and insert a percussion cap beneath the hammer. Regardless, he managed to get off more than one shot before the Apaches killed him.

Thanks to Donnell’s sacrifice, Tappan and the other survivors made it to the ridge and then headed into the desert. The Apaches didn’t pursue for long; they were more interested in the mules. A few stripped Donnell’s body before returning to the wash, where fellow tribesmen were butchering the dead mule and torturing the still-breathing Powell. Afterward, they stripped and mutilated the bodies of Privates Powell and Richards and Captain Millar.

The six survivors struggled onward in the desert. They crossed three drainages, skirted stands of cholla cactus and fought their way through mesquite and catclaw thickets that tore at their clothes. Dazed from his head wound, Snowden wandered away from his comrades. (Days later the private stumbled into Maricopa Wells and from there was taken to Fort McDowell, where he later died.)

The others trudged along in a southwesterly direction, Tappan’s progress slowed by his wounds. As his foot continued to swell, he cut away part of his boot. Once the men were convinced the Apaches were not pursuing them, they took more rest stops. Tappan needed every one of them. The group spent that first night in the desert.

On Friday morning, the slow march continued, with dehydration, hunger and heat all taking a toll on the desperate group. Surgeon Tappan made a heroic effort to keep going, but he knew he was holding back the others. The next morning he realized he could go no farther. At about 9 a.m. he ordered Private Pedro Sanchez and another private to remain with him and sent Corporal Berg and the teamster Sumner to look for water.

Berg and Sumner had little luck on their mission. They not only failed to locate any water but also became disoriented. The inhospitable desert looked the same in every direction, and the two were unable to find their way back to Tappan and the two privates. In the distance, through shimmering heat, they could make out Picacho Peak, and though it was at least 30 miles away, they headed in that direction. Sumner knew that the stagecoaches of the Butterfield Overland Mail passed that way, and it was the most likely place to wet their parched throats.

On Sunday, March 25, Berg and Sumner reached the peak, but to their dismay, they found no water. Surely they would perish. They lay down in the shadows and awaited death. Two hours later, they heard men and horses, which turned out to be a military detachment, led by Assistant Surgeon John E. Kunkler, making its way from Tucson to California. Kunkler gave them food and water and listened to their accounts. Berg was incoherent, but Sumner was clear about the tragedy. Kunkler immediately sent a dispatch to Tucson, describing the ambush and aftermath to Brig. Gen. John S. Mason, commander of the District of Arizona.

On receiving the news, Mason ordered Captain Jonathan B. Hager of the 14th Infantry to proceed with a 20-man force from Tucson to Cottonwood Spring, near Cottonwood Wash and about 17 miles from Fort Grant. The general also sent a courier to Fort Grant, instructing its commanding officer, Lieutenant Edmund Burgoyne, to take 35 men to Cottonwood Spring and await Hager’s arrival.

Hager actually had a command of 23 men when he departed Tucson at 6 a.m. on Monday, March 26. Just two hours later, Mason received word that a private from the escort wagon—one of the two who had remained with the wounded Dr. Tappan—had been found at Point of Mountain, about 16 miles northwest of Tucson. The private said that on Sunday morning, March 25, Tappan had ordered him to try to find water. The news encouraged Mason, but he knew he must act fast to save the assistant surgeon. He appealed to local citizens, and several Mexicans familiar with the area offered to guide a rescue party led by Captain John Green, Mason’s adjutant. An expert tracker and other Tucsonans also assisted.

Hager and his men marched 32 miles that Monday and resumed their search at first light on Tuesday. They found signs of recent Apache activity in the area and were ever watchful as they followed a barely discernible trail on a beeline to Cottonwood Spring. The detachment reached the spring without incident to find Burgoyne’s waiting force.

On Wednesday, March 28, Hager wrote in his journal: “I took Lieutenant Burgoyne and 40 men and proceeded to find the place where the attack had been made. About 10 a.m. and about 13 miles west of the springs, we came to it. The first thing we saw was the major [Frank Millar]; a very few more steps brought us upon the spot. A horrible scene was presented to our view. In sight were their bodies, bloated and festering in the sun where they have lain for six days. All were stripped, and in the body of the major were stuck nine arrows, making him look like a porcupine more than anything else. More or less arrows were in the bodies of all. One of the men was scalped.”

Hager knew there had been 10 men in the wagon, leaving six unaccounted for, among them Dr. Tappan. He detailed men for burial and search parties, then climbed to the top of the ridge and began sketching the scene before him. Meanwhile, Charles H. Meyer, a Tucson druggist whom the Army had contracted as acting assistant surgeon for the detachment, examined the mutilated, decomposing bodies and reported:

The body identified as that of Major Millar by Captain Hager and Lieutenant Burgoyne was found lying north of the road and within about 40 feet of the wagon, with a bullet wound in the left side, the ball entering between the fifth and sixth ribs, passing through the heart and passing out of the body under the right arm. Another bullet wound between the shoulders passing clear through the body, and in its course breaking the spinal column. From the situation of the wounds and their effects, death must have been instantaneous. The Indians stripped the body, cut off the “genital organs” and upper parts of the ears, then turned [it] over on its face and shot nine arrows into the back, which were sticking in it when I saw the body….

The body of a man unknown [was] found lying about 60 feet west from the wagon and close to the road, with three bullet wounds in the upper part of the body and one in the right thigh. From the nature of the wounds, said man might have lived several hours. From indications this man must have fought before he died, for he is the only one who I believe was tortured after he fell into the hands of the Indians. His left arm was broken close to the shoulder and twisted until it assumed the appearance of a twisted rope; his whole scalp was skinned off from the eyebrows upward down to the back of his neck; whereas in scalping a victim after death the Indians merely cut the central portion of the scalp, and from the above indications, therefore, it is almost certain that this man was tortured before he died. After stripping the body, the Indians fired seven arrows into the back, which were in it when seen by me.

In Tucson, General Mason was anxiously awaiting word from Hager and Green. On Thursday, March 29, the other private that had remained with Tappan arrived in Tucson, following his recovery at Blue Water Station, near present-day Coolidge. He reported that on Sunday, March 25, Tappan had told him to save himself, as the doctor did not expect to live. Further bad news arrived with Green, who could not find Tappan. But Mason had known Tappan as a friend in Steubenville, and he refused to call off the search.

Captain Hager was still looking, too, though supplies were getting low. His detachment continued on to Picacho Peak, arriving by 7 p.m. on March 29. The party found no signs of survivors or water, and some of the searchers themselves were becoming faint or delirious. Hager sent his guide ahead to Point of Mountain to fill the canteens while the soldiers rested before following just after midnight. Shortly after sunrise on Friday the 30th, the party met the guide. Hager wrote in his diary: “We have marched since yesterday morning about 62 miles on one canteen of water. I rested here until 1 p.m., when I started for Tucson, 16 miles distant, leaving the men to follow in the night. Reached home about 5 p.m. tired, dirty and sleepy.”

In Tucson, Captain Green assembled the best local trackers, and on Saturday, March 31, he led another search party. Mason authorized 10 days’ rations. “I still have a party out in search of Dr. Tappan but with little hope of finding his remains,” Mason noted in mid-April. “I employed the very best scouts in the territory. Kept them out until they declared further search useless.” Green’s party reported finding tracks into the Tortolita Mountains north of Tucson, but the trail ran cold.

Tappan most likely did not survive more than a few days beyond Sunday, March 25. A year and a half later, a body turned up near the Cañon del Oro; it was thought it might be Tappan, and officials requested an autopsy. If ever done, the results are not recorded. Details of Tappan’s last days remain unknown.

Seldom did Apaches leave survivors when ambushing small parties. In this case, a teamster and three soldiers did cheat death, because the Apaches were focused on carving up a dead mule, torturing a survivor and making off with the other three mules. Still, six men were dead, including two promising officers. The Army recovered their bodies in 1867. Millar’s remains rest in the family plot at Riverside Cemetery in Albany, Ore. Tappan’s remains, on the other hand, might have lain above ground all these years on land that, except where flash floods have carved it, looks much the same as it did 144 years ago.

Doug Hamilton of Kearny, Ariz., Berndt Kühn of Stockholm, Sweden, and Larry Ludwig of Bowie, Ariz., have visited the ambush site, which lies on state trust land. The Arizona State Land Department requires permits and prohibits artifact collecting. This article was adapted from the three authors’ “Military Debacle in Cottonwood Wash” in the August 2009 issue (No. 86) of The Smoke Signal (send $7 plus $2 shipping to the Tucson Corral of the Westerners, P.O. Box 40744, Tucson, AZ 85717).