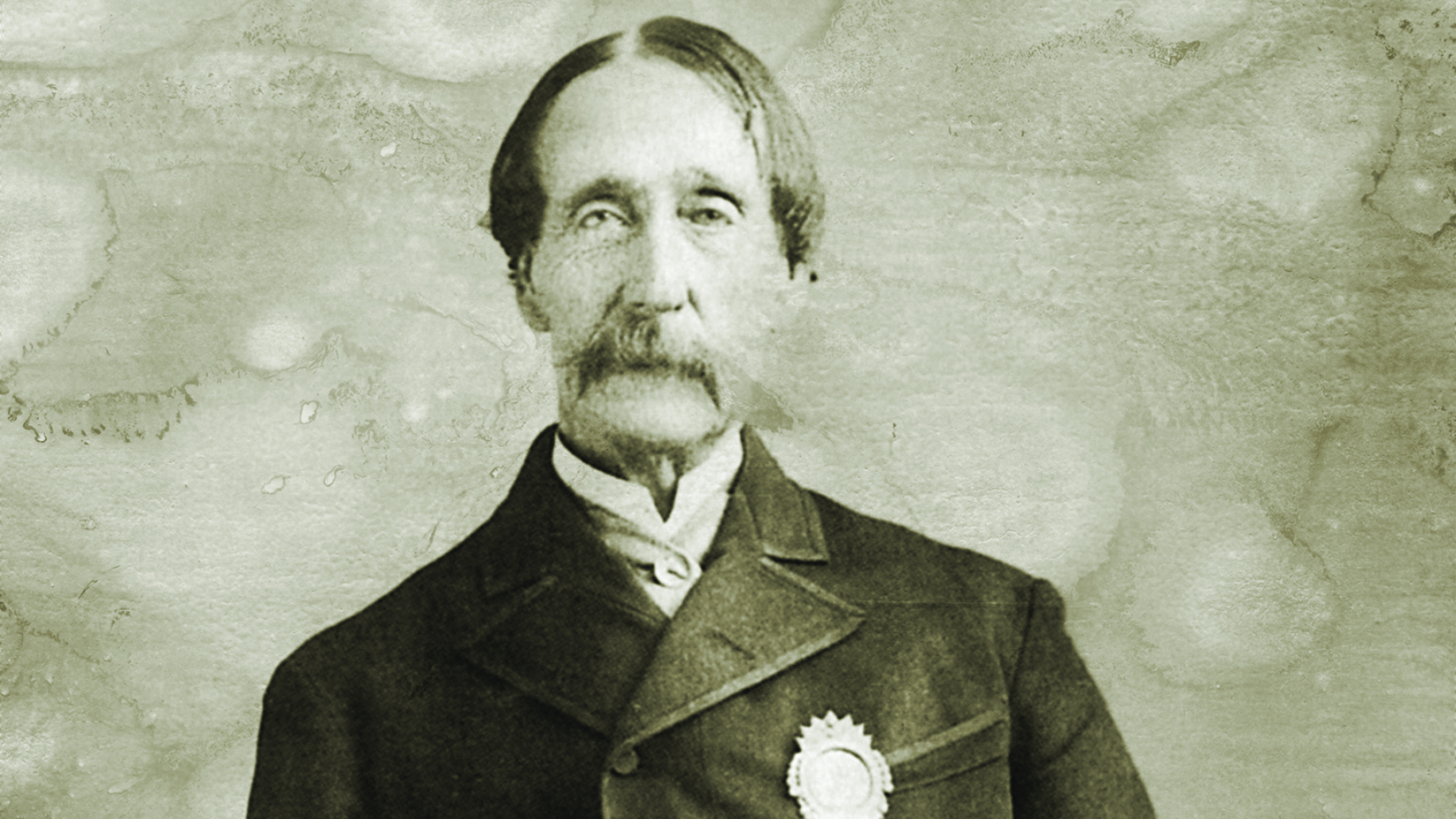

Crashing through a skylight into a Manhattan saloon to break up a dog fight in December 1866 was only one of Henry Bergh’s more memorable exploits as a pioneering animal-rights provocateur. “Mr. Bergh’s figure was of course a very familiar one about the city. His appearance was striking,” a newspaper reported. “His face was long and thin, much resembling the picture of Don Quixote, with sunken eyes and prominent cheekbones. His attire was always faultlessly neat.” A shipbuilder’s son, Bergh grew up with wealth. He came to his cause in mid-life after failing as a playwright. Being a meat-eating, fur-wearing worldly New Yorker with neither pets nor children did not deter him from campaigning against cruelty to animals, a crusade that helped bring the first American child protection organization into being.

Others had preceded Bergh in animal activism. In colonial times, the Puritans outlawed cruelty to beasts, to the point of sometimes assigning individual creatures agency, as when communities put animals on trial, prosecuting a pig that had run amok in a town or sparrows that had eaten seed stocks. The early republic’s first state law protecting animals, an 1828 New York statute, set a pattern, emphasizing safeguards on animals as property. Bergh took a different path, founding a movement to protect animals from cruelty based on a moral imperative to spare them suffering. Traveling in Spain he had been particularly disgusted by bullfighting. In Russia, where he briefly served as a diplomat during the Civil War, mistreatment of horses distressed him. En route stateside after his tour in Russia, he stopped in London, where he met with the president of the Royal Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, an organization established in 1824.

Bergh resumed life in New York. In April 1866 he enlisted friends and community notables to join him in establishing the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals, whose “Declaration of the Rights of Animals” he wrote. The New York legislature granted the group a charter; members included fellow swells J.J. Astor, Peter Cooper, John Van Buren, Hamilton Fish, and others. Within a year, New York legislators had passed an expansive law addressing maltreatment—including abandonment, maiming, and starvation—of not just work animals, but all living creatures held captive.

ASPCA agents were deputized to arrest violators, and Bergh was known personally to disrupt a beating being given a sick or disabled horse—and to turn his wrath on the driver. He had no shortage of occasions for intervention. In mid-1800s New York City, horses outnumbered residents, and under urban strain the bonds that had enforced kindness to animals in rural America lost their hold. Besides battling the widespread abuse of horses by streetcar operators, Bergh also fought for humane methods of slaughtering cattle and hogs. He harried impresarios of dog and cock fighting, which though banned still were prevalent. He brought public attention to needless cruelty inflicted on commoditized animals, from turtles to chickens and calves, being shipped alive to market. He devised a sling in which to transport disabled horses. He persuaded New York City officialdom to install fountains for watering horses.

Epithets rained on Bergh by commentators ranged from “Angel with a Top Hat” to “The Great Meddler” and “An Ass That Needs His Ears Cropped.” He knew his place. “[My] practice, and recommendation,” he told a Philadelphia colleague, “is to keep agitating; and keep continually in the newspapers with our cause.”

Early on, Bergh tangled with P.T. Barnum, calling out the showman for the cruelty his performances inflicted on animals. Eventually the two became friends; Barnum advised Bergh to buff his brand. Bergh also agitated for food safety, helping to shame and prosecute sellers of tainted milk from weak, diseased cows held in horrible conditions and fed not grain and grass but distilleries’ used grain waste.

Despite his robust activism—he was 53 when he crashed through that saloon skylight—Bergh was the antithesis of the warm, fuzzy do-gooder. “He did not love horses; he disliked dogs. He was a healthy, clean-living man, whose perfect self-control showed steady nerves that did not shrink sickeningly from sights of physical pain,” a biographer wrote in 1902. “No warm, loving, tender, nervous nature could have borne to face it for an hour, and he faced and fought it for a lifetime. His coldness was his armor, and its protection was sorely needed.” Bergh’s ardor, however, matched his background. His wealthy father was said to have paid black and white workers the same wages, and the son had supported the ending of slavery. The formal establishment of civil rights for blacks, elevating them from the animalistic status slavery had assigned them, may have fired his passion for creatures’ welfare. The rise of post-war industrial America aroused in him concerns about the treatment of animals in commerce.

In 1874, a Methodist case worker in midtown Manhattan alerted Bergh to a helpless “creature/animal” she said was being abused. Bergh promised to help, whereupon his informant identified the “creature” as a young girl she had heard about from the landlord of the building where the child lived. The case worker had brought the matter to the police and a lawyer; in neither arena did she find any willingness to help. Bergh’s lawyer, Elbridge Gerry, obtained testimony from the child and her neighbors. “The child is an animal,” Bergh told officials. “If there is no justice for it as a human being, it shall at least have the rights of the cur in the street.” City authorities removed the girl from the premises and prosecuted the abusive guardian, who went to prison. The following year Bergh and Gerry formed the New York Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Children, the world’s first child protective agency. Bergh amplified his message far beyond New York on lecture tours, and to broaden the ASPCA’s membership and power he invited women into the society.

Living his motto—“Mercy to animals means mercy to mankind.”—Bergh pressed his cause without relent. “Day after day…I am in slaughterhouses, or lying in wait at midnight with a squad of police near some dog pit; through the filthy markets and about the rotten docks,” Bergh wrote, Andrew Robichaud noted in his 2019 book, Animal City: The Domestication of America. “Out into the crowded and dangerous streets; lifting a fallen horse to his feet, and perhaps sending the driver before a magistrate; penetrating dark and unwholesome building where I inspect collars and saddles for raw flesh; then lecturing in public schools to children, and again to adult Societies. Thus my whole life is spent.”

Upon Henry Bergh’s death in 1888, poet Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, in a eulogy, quoted an 1872 poem of his about the man: “The man I honor and revere/Who without favor, without fear, In the great city dares to stand/The friend of every friendless beast…”

This story appeared in the August 2020 issue of American History.