Hudson River horticulturalist created a new home-and-garden style for the new republic

IN MID-19TH CENTURY AMERICA, riverboats ranked high among modes of transport. Building and maintaining heads of steam by burning wood or coal, these vessels worked any river of any significant size. Hudson River steamboats burned anthracite coal. Stokers also kept handy “fat pine” logs that burned hot enough to push a paddle-wheeler to 22 mph, even carrying passengers and freight. A reputation for speed meant more business, although engine explosions and fires, as well as accidents, were as common as the practice of captains racing, usually surreptitiously, along their assigned routes, as was so on Wednesday, July 28, 1852, when the steamer Henry Clay, out of Albany, New York, docked 90 miles down the Hudson River at Newburgh to board passengers.

The Clay, a fixture on the Albany/New York City circuit, was a typical double-paddle wheeler, 198 feet long and powered by a walking beam engine, so called from the rhythmic motion of the pistons driving the paddles. The engine room was amidship. Captain Thomas Collyer had built the Clay and a similar vessel, the Armenia, the year before. This day he was commanding the Clay. The Armenia was also on the river, commanded by Captain Isaac Smith.

Among those waiting at Newburgh when the Clay tied up early that afternoon was Andrew Jackson Downing. Accompanied by family and friends, Downing, 36, was bound for New York City, then Newport, Rhode Island, on business—specifically, a conference on designing the grounds of the Smithsonian Institution and the Mall in Washington, DC. Besides his work as a pioneering planner of demesnes for American institutions and America’s wealthiest residents and editor of the popular magazine, The Horticulturist, Downing was a best-selling author. His architectural pattern books were popular resources from which the wealthy and folks further down the economic ladder took the designs for their residences. Unknown to Downing and fellow passengers, that day Captain Collyer was racing Captain Smith to Manhattan.

Downing and companions and others boarded, crewmen cast off, and the Clay resumed speed, its huge pistons pumping hard. At 2:45 p.m. the Clay was passing Yonkers, New York, when fire broke out in the engine room. The pilot turned the Clay east, toward the New York shore, grounding the bow and allowing those forward to escape but putting the ship’s blazing midsection between passengers and crewmen at the stern and safety. The ship had two lifeboats; there was no time to launch them. Those who could, swam—or drowned, pulled under by those who could not. Those who stayed aboard burned to death.

Of the Clay’s 500-some complement, 70 died, including many with names known nationwide. Andrew Jackson Downing was one, along with his mother-in-law, Caroline DeWint. Downing’s and DeWint’s deaths devastated their families—but also left The Horticulturist without an editor and deposited in the hands of Downing’s business partner Calvert Vaux and his friend Frederick Law Olmsted plans Downing had roughed out for a monumental park in upper Manhattan.

Although his career lasted barely 16 years, Andrew Jackson Downing almost single-handedly reoriented landscape design in the United States away from Europe’s geometry and classicism and toward a less formal style better bespeaking the national character. He helped America find its face in its gardens and its rural architecture. Downing’s writings “cut across all segments of society, which is why he had such an impact nationally,” says Kelly Crawford, museum specialist at Smithsonian Gardens.

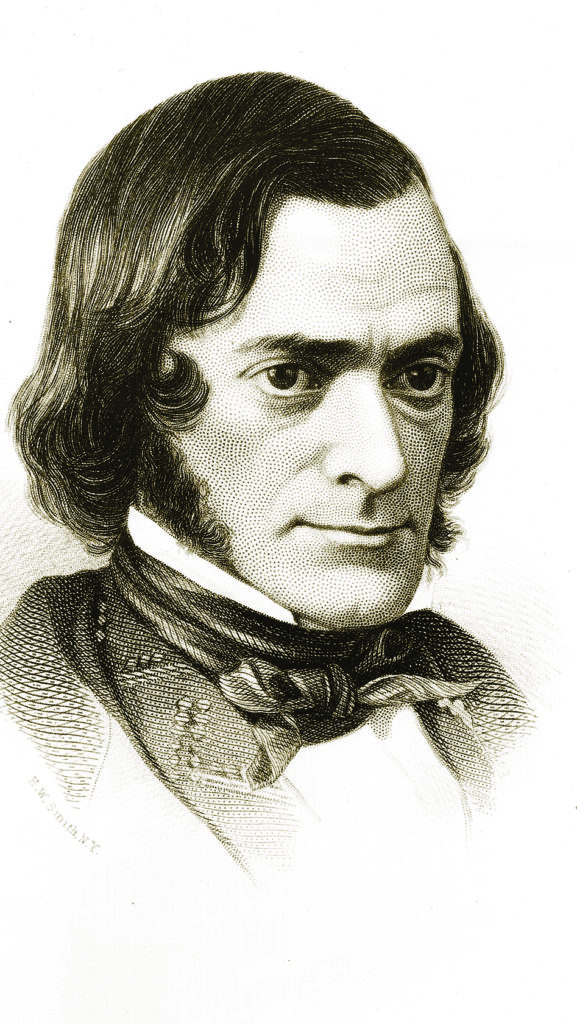

Born on Halloween 1815 in Newburgh to nurseryman Samuel Downing and wife Eunice Bridge, Downing was the youngest of five children. The Hudson Valley of his boyhood was a fascinating place, with a wide variety of plant life, topography, and splendid architecture in the form of rich residents’ mansions.

Young Downing’s winning personality, combined with an interest in houses and gardens rooted in the family business, Botanic Gardens and Nurseries, brought him into those mansions, onto their grounds, and into their owners’ company, where he flourished.

At 16, Downing left school to help older brother Charles run Botanic Gardens and Nurseries. Work steeped him in the practical details and aesthetics of landscape gardening and triggered an interest in architecture.

At 19, Andrew was publishing essays on these topics in the Magazine of Horticulture and other major publications emphasizing the need to view house and garden in tandem and to suit residences to their surroundings.

For a dwelling’s shape, layout, and detail, many homeowners and builders relied on books—essentially, catalogs reproducing drawings of architectural and artistic designs and individual elements. This tradition dated to Roman times, when in his Ten Books on Architecture the military engineer Vitruvius prescribed how a residence or institutional building should look and function. The Vitruvian bywords were “firmness” (solidity), “commodity” (utility), and “delight” (beauty). This ethos carried through the Middle Ages into the Renaissance, when innovators like Italian architect Andrea Palladio emulated Vitruvius by publishing books from which Palladio’s and other designers’ clients could select the bits and pieces that would give their houses the desired look and feel. In the late 18th and early 19th centuries, architectural guides by such authorities as Minard Lefevre and Asher Benjamin, often adapting Roman and Greek styles through a British lens, instructed carpenters and craftsmen and offered technical drawings on which to base houses. However, the drawing often was only a floor plan, with no notes on its exterior.

A younger school of pattern book authors in Britain was compiling images of less classically inflected design. An Encyclopaedia of Cottage, Farm and Villa Architecture and Furniture, by John Claudius Loudon, published in 1832, and 1835’s Rural Architecture, by Francis Goodwin, emphasized a less formal approach.

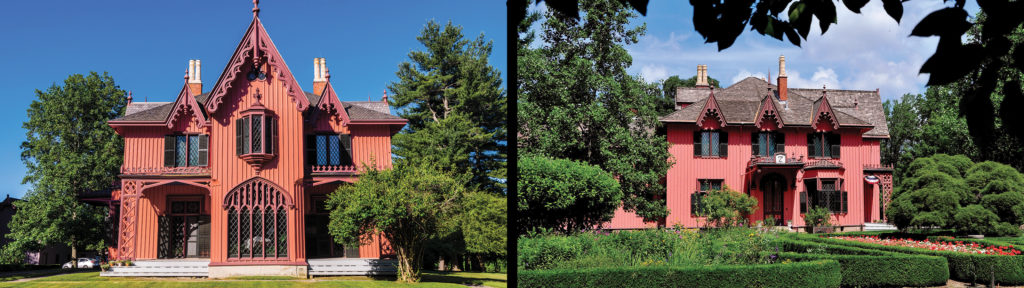

Downing’s study of these volumes strongly influenced his ideas of how houses should look and feel. Upon marrying Caroline DeWint in 1838, he set about building a residence for them in Newburgh. Classical was the regnant style but, working from Loudon and Goodwin and their precepts, Downing went Gothic, with pointed roofs, twin towers flanking an entranceway, and clustered chimneys.

All the while Downing was thinking about landscape design. In 1841, he published A Treatise on the Theory and Practice of Landscape Gardening, Adapted for North America; with a view to the improvement of country residences. His focus was gardening and landscaping, but Treatise also featured a dozen drawings of houses, including the Downing residence. The book, heavily indebted to Loudon and another English writer, Humphrey Repton, sold through three editions and made Downing a celebrity.

His adaptation of design to the North American setting appealed to the market. Downing introduced readers to the architectural trends known as the Beautiful and the Picturesque. These movements refracted the romantic aesthetic of the day in literature and art. “Treatise, followed by his second book Cottage Residences, were the pivotal points in Downing’s career,” Crawford says. “While Treatise was geared to wealthier Americans, Cottage Residences provided a kind of pattern book for more people of more modest means.” Although not a pattern book, Treatise foreshadowed things to come, and also overshadowed a pattern book partially published in 1838 by Downing’s friend, the architect Alexander Jackson Davis, who drew the dwellings in Downing’s Treatise but never completed his own pattern book project.

Downing was 27 when he published Cottage Residences in 1842. His manifesto departed from the schools of Lefevre, Benjamin, and their ilk. Downing was writing for the public, organizing information so consumers could understand and use it. A Downing pattern book—and soon, competitors by other authors—coached would-be homeowners on how to show an architect or contractor what to build. Cottage Residences, the first American house pattern book to benefit from advances in printing technology and distribution method, remained in print the rest of the century.

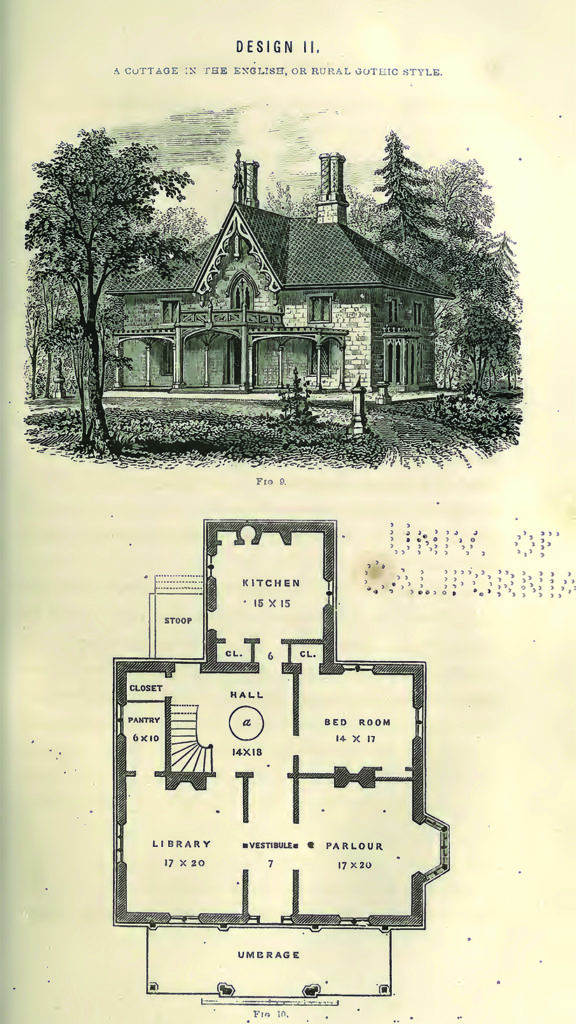

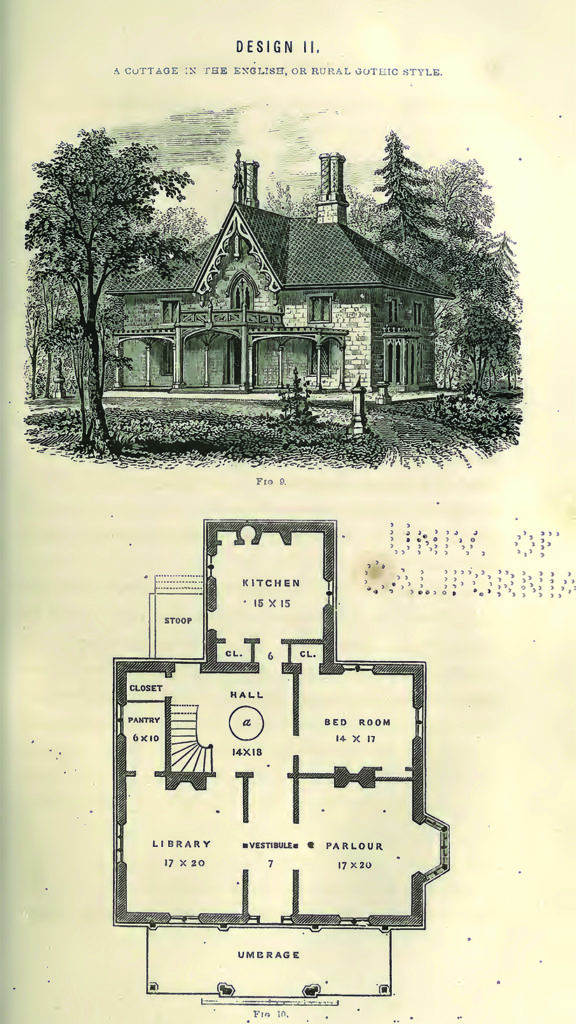

Downing began Cottage Residences with “Architectural Suggestions,” his take on the Vitruvian triad. Instead of “firmness, commodity and delight,” Downing advocated fitness—for the owner’s style of life and the building site; purpose—working farmhouse, cottage, or villa, telegraphed by chimney type and the leisurely presence of a veranda; and architectural style. British forms, bowing to British weather, avoided roofed exterior spaces. Downing fitted his model houses with expansive porches. Each chapter discussed a particular style of home, including exteriors and interiors, offering both a floor plan and a design for garden and grounds—a unified residence combining beauty and function. Downing himself designed and sketched eight of the 10 houses, including Design II, “A Cottage in the English or Rural Gothic Style.” That drawing was rendered in final form by Davis, who contributed one of the other two houses; the last was by John Notman. Aiming to appeal to rural residents and city dwellers able to afford a country house, Downing wrote conversationally. However, he was off the mark. Houses in Cottage Residences, even “cottages,” were far beyond the means of most.

Between the 1842 appearance of Cottage Residences and Downing’s second pattern book, The Architecture of Country Homes, in 1850, he was busy writing, completing commissions, and undertaking civic projects. With brother Charles he wrote a book on pomology—the study of fruit—meanwhile updating Treatise and Cottage Residences. In 1846, he accepted the editorship of The Horticulturist and Journal of Rural Art and Rural Taste, probably the first American periodical whose every edition featured an architectural or landscape design—in this instance, many by Downing. The magazine gave Downing a platform from which to promote his ideas regarding rural architecture. The periodical’s popularity helped establish him as the American tastemaker in rural architectural design.

Country Homes also reflected Downing’s evolution in his approach to design as well as indirectly responding to complaints about the cost of trying to build from Cottage Residences. Country Homes presented designs ranging from simple, truly inexpensive farmhouses and cottages to expansive villas. Downing kept his conversational style, arguing amiably on behalf of good taste even on a shoestring. The best-selling book spoke to a growing middle class, which embraced Downing as a practical theorist and made his ideas a go-to destination for planning a residence.

Country Homes opened with “The Real Meaning of Architecture,” an exegesis on Downing’s vision, followed by designs for 13 cottages, nine original; four had run in The Horticulturist. This first section also covered six farmhouses. Part II presented 14 villas, seven of which were Davis renditions based on Downing designs, with contributions by Davis, Richard Upjohn, Russell West, and Gervase Wheeler.

Previously, American dwellings generally had a center hall flanked by rooms. Downing introduced an irregular, organic layout. Doing penance for his pricey faux pas in Cottage Residences, he recommended economical ways to meld materials and design, as in using wood for board-and-batten exteriors and combining stone and stucco on cottages. He gave big play to brackets—cornice scrolls—and rural Gothic styles without neglecting the Italian villa and other themes.

Country Homes included exterior ornamentation, interiors, and furniture, not addressed in Cottage Residences. Few photographs exist of 1850-era residential interiors; filling that gap, Country Homes offers glimpses of antebellum middle- and upper-class life in rural America. Downing also discussed the practical matters of heating and ventilation as essential to comfort. Country Homes stressed suitability: a cottage should look like a cottage; a farmhouse, like a farmhouse. Neither adjuration precluded beauty; rather, according to Downing, a residence should reflect its purpose and its family’s lifestyle.

Downing’s influence extended to public spaces. He had long advocated lawns and gardens as settings for residences. On an 1850 trip to Europe he experienced public gardens and parks such as those in London’s West End and Munich’s Englischer Garten. The following summer, noting America’s lack of public parks, he wrote to New York City Mayor Ambrose Kingsland to urge that the city dedicate at least 500 acres in upper Manhattan for a “New-York Park.” Downing plumped for such a project in the August 1851 Horticulturist, arguing that metropolitan residents deserved a landscape in which all could experience the outdoors. Kingsland went for the notion, setting in motion legislation that would set aside acreage and establishing a commission to oversee creation of a “central park.”

Upon Downing’s death, Vaux and Olmsted ran with his idea, first persuading the Board of Commissioners of the Central Park to hold a competition to pick an architect to design the park. The two fleshed out Downing’s preliminary drawings. Their “Greensward” plan won the competition, and in 1858 construction began of what became the emerald gem at Manhattan’s heart. That project’s success and other achievements, such as Prospect Park in Brooklyn, immortalized Olmsted, a prominence that eclipsed Downing’s.

The Henry Clay disaster, the Hudson’s worst ever, stampeded Congress into passing the Steamboat Act of 1852. Steamer captains now had to be licensed; vessels had to undergo safety inspections. Racing was banned, a proscription sometimes honored in the breach but definitely curbed. Steamboat deaths declined from more than 1,000 in 1851 to 45 in 1853.

Downing barely established an oeuvre of landscape and architectural projects. Houses built to his vision underwent renovation. Fashions changed. His honeymoon home was demolished in 1922. However, Downing’s legacy endures, articulating as it does a sensibility transmitted by Downingesque elements in countless houses: central gables, scrolled ornamental brackets, clustered chimneys, and, above all, porches. Downing’s default design was the single-family residence surrounded by lawns, gardens and trees, a combination that describes millions of American residences.

Former partner Calvert Vaux and his associate, Frederick Withers, enjoyed success for years treading where Downing might have. Many houses Vaux and Withers built departed from Downing’s pattern book designs and those he put forth in The Horticulturist but nonetheless hewed to his dictum of unity between house and setting. Consider artist Frederick Church’s Hudson Valley home, Olana, designed by Vaux with much input from Church and built 1870-72 (“Saving Olana,” August 2018). An eclectic blend of Victorian and Middle Eastern elements, the house and grounds harmonize beautifully.

Succeeded by Vaux’s 1857 Villas and Cottages, Downing pattern books sold well into the early 20th century, presaging a 21st century revival that is seeing builders, often renovating residences in decades-old suburban developments, look to the past for touches that set a dwelling apart from its mass-market context. Planners use pattern books to help homeowners select historically correct designs. Downing’s overall approach never became dated. Enthusiasm for renovation and rehabilitation has spawned stacks of magazines and hour upon hour of cable television devoted to shelter—a vast and mutating multimedia pattern book advocating, as Andrew Jackson Downing did, on behalf of good taste and harmony interweaving dwelling, furnishings, and landscape.