Working for newspapers in Chicago and St. Louis, reporter Theodore Dreiser had written about the harsh social conditions in the belching factory cities powering America’s industrial revolution. In March 1894 he wanted to get a good look at Pittsburgh and neighboring Homestead, Pa., a place that was so teeming with smokestacks that some called it “hell with the lid taken of.”

It was at Homestead some 15 months earlier that one of the worst labor-management confrontations in American history had occurred. Citing falling steel prices, Carnegie Steel chairman Henry Frick announced that the wages of skilled workers at the Homestead factory would be cut 15 percent—no matter that Carnegie Steel was the highly profitable leader of the booming U.S. steel industry or that its already poorly paid workers toiled 12-hour shifts in brutal conditions. Frick’s contract offer was designed to break the Amalgamated Association of Iron and Steel Workers—and he was successful, but not before a July 6, 1892, showdown between 300 Pinkerton guards and a crowd of steelworkers and supporters devolved into an exchange of gunfire, leaving seven workers and three guards dead and scores wounded. The violence made headlines around the world.

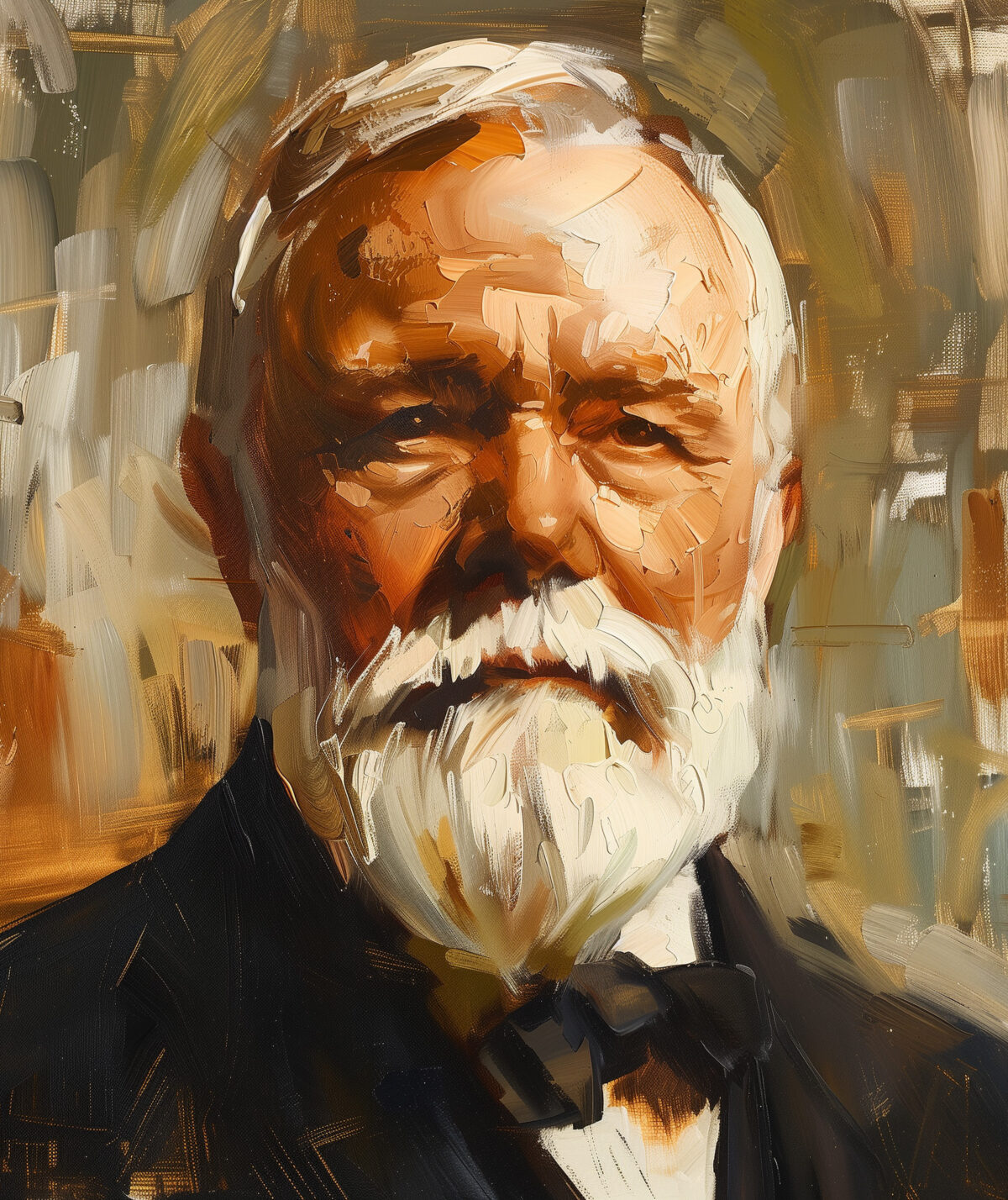

Frick later chortled in a letter to his boss, Andrew Carnegie, that they had taught the workers “a lesson they will never forget.” On the day of the Homestead battle, Carnegie, one of the richest men in the world, was being feted in Aberdeen, Scotland. When questioned by reporters, the tycoon called the violence “deplorable” but otherwise pleaded ignorance, saying, “I have given up all active control of the business.” In a letter to British prime minister William Gladstone, Carnegie called the effort to break the union a “foolish step” and blamed Frick for the violence. “It is too much to expect poor men to stand by and see their work taken by others—their daily bread,” he wrote. But Carnegie was lying. Frick had apprised his boss of the goings-on at Homestead in the days leading up to the showdown and Carnegie approved Frick’s actions, just as he’d sanctioned Frick’s defeat of Amalgamated at the company’s Edgar Thomson Steel Works three years earlier.

Reporter Dreiser described the “depressing” scene he witnessed in Homestead in the aftermath of the tragedy. A “sense of defeat and sullen despair” hung over the town, he wrote, as did a miasma of dark, polluted air. The worker living areas behind the factory were squalid—dingy-gray frame structures, 50- cent brothels, scruffy children and trash. The roads were unpaved and there was no sewage system. The area was “so unsightly and unsanitary as to shock me into the belief that I was once more witnessing the lowest phases of Chicago slum life—the worst I’d ever seen.”

Two days later, Dreiser toured east Pittsburgh’s Oakwood neighborhood, where steel company owners and executives lived. There, he reported, were homes of “the most imposing character…with immense lawns, great stone or iron or hedge fences and formal gardens and walks of a most ornate character.” Dreiser also visited the “huge and graceful library of white limestone” being donated to Pittsburgh by Carnegie along with the new Phipps Arboretum, a gift from Carnegie’s business partner, Henry Phipps. Wrote Dreiser: “Truly, never in my life, I think, neither before nor since…was the vast gap which divides the rich from the poor in America so vividly and forcefully and impressively brought home to me. . . . The poor were so very poor, the rich so rich, and their self-importance was beyond measure.”

Dreiser reflected on the wide financial divide that marked America’s industrial revolution—great economic progress and vast fortunes built on the labor of the working poor. And no man played a bigger role in this fraught tableau than Andrew Carnegie, the wee Scotsman who parlayed brilliant business instincts and impressive personal qualities—a charmingly forceful nature and what the British writer John Morley called his “invincible optimism”—into one of the most successful, if contradictory, lives in American capitalism. He was a man driven to accumulate huge wealth only to give it all away.

Carnegie invested in the right industries at the right time— railroads, telegraphy, oil, iron and steel—to become very rich at a young age. Tough struck by occasional pangs about his “debasing” fondness for money, Carnegie grew more avaricious with time. As a devotee of philosopher Herbert Spencer, who coined the term “the survival of the fittest,” social Darwinism gave Carnegie an intellectual framework by which to justify his tough, laissez-faire attitude. In 1889 Carnegie penned a defense of capitalism and the law of competition mixed with a code of conduct for plutocrats, The Gospel of Wealth. Carnegie argued that business owners were “essential for the progress of the race,” while labor was a cog in the wheel of social and material advancement. But, proclaimed Carnegie, the rich had a high social obligation to spread their money—while still living—“for noble aims.” A decade later, Carnegie would follow through on that belief after selling his steel company to J.P. Morgan in 1901 for some $480 million, of which he retained $225 million (more than $6 billion in today’s dollars). He then spent the rest of his life giving money away—an estimated $350 million in total to a variety of causes. He became “a national treasure and not a robber baron,” wrote Peter Krass in Carnegie, and a model for latter-day moguls such as Warren Buffet and Bill Gates, who have pledged to put most of their fortunes to beneficent use before they die.

Carnegie was born in Dunfermline, Scotland, in 1835. His father was a talented but mostly unsuccessful handloom weaver, and his mother did odd jobs to support the family. When Carnegie was 12, the family moved to Allegheny City, Pa., adjacent to Pittsburgh, joining relatives who’d immigrated to America. Pittsburgh “was filled with enterprising, upward-rising Scotsmen,” writes Carnegie biographer David Nasaw, and Andy Carnegie would become one of them. He had very little formal education, but he was a fast learner and a spirited fellow; even at a young age, notes Nasaw, “there was something about the lad that inspired older Scottish men to entrust him with responsibilities.” He moved quickly through the ranks at a cotton mill, doubling his pay to $2 a week before leaving for a job as a messenger at the Atlantic and Ohio Telegraph Company. Before long he was an operator. Working equally hard to educate himself, he spent much of his free time in Allegheny City’s first quasi-public library, reading voraciously, especially books about his new country.

Soon came the connection that would profoundly change Carnegie’s life. In 1853 the Pennsylvania Railroad started erecting its own telegraph wires along the route from Philadelphia to Pittsburgh, the gateway to America’s westward expansion, to keep track of its trains. Tom Scott, the railroad’s western division superintendent, hired Carnegie as his personal telegraph operator. The eager teen soon became Scott’s chief assistant and began learning the business from Scott and Pennsylvania Railroad president J. Edgar Thomson. In 1855 Scott loaned Carnegie $500 to buy stock in a privately traded mail delivery company that had just secured a contract with the railroad. The arrival of Carnegie’s first dividend check sparked an epiphany. “I shall remember that check for as long as I live,” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography. “It gave me the first penny of revenue from capital—something that I had not worked for with the sweat of my brow. ‘Eureka!’ I cried.”

Carnegie had hitched himself to two men running a thriving, expanding railroad, and over the next 15 years all three would make fortunes from investments in companies doing business with the railroad—self-dealing financial activity that was unethical and would be illegal today but was somewhat common in the late 19th century when there were few anticorruption laws. Knowing that wooden bridges were not strong enough for longer and heavier trains, the trio, along with three engineers, organized the Piper & Shiffler (later Keystone) Bridge Company, which got lucrative contracts from the Pennsylvania Railroad and flourished for years. Thomson and Scott hid their holdings behind the identities of others. Knowing planned routes for new westward rail lines, Thomson, Scott and Carnegie bought land where stations and rail yards—and then later towns and cities—would arise. Carnegie also made a very successful investment in a Pennsylvania oil company. By late 1863, according to Nasaw, the 29-year-old Carnegie had equity stakes in 15 companies, half of which had large contracts with the railroad, and a listed income of nearly $48,000—nearly $8.5 million today.

When the Civil War broke out, Carnegie paid an Irishman $850 to fight in his place for the Union and continued his financial wheeling and dealing. Between 1866 and 1872, he was buying, selling and manipulating securities on a grand scale, a practice he’d later condemn. His wit and bonhomie, his financial acumen and penchant for shameless flattery made him a consummate salesman. In 1867 Carnegie set up a telegraph company with a contract to string lines along Pennsylvania Railroad routes. Before the poles were up he’d sold the firm to the more established Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph Company for a stake in the acquiring company. Carnegie then gained control of Pacific and Atlantic Telegraph, in which Tomson and Scott were also invested, and then all three men exchanged their shares in that firm for a more valuable stake in Western Union, the market leader. Carnegie was always trading up. He had a genius “for buying and selling shares in companies whose assets he knew were worth far less than the value of their stocks,” writes Nasaw in his 2006 book Andrew Carnegie.

In 1868 the 33-year-old Carnegie was living with his mother in the swanky St. Nicholas hotel in New York City; he made $50,000 annually and had assets worth $400,000. But, notes Krass, “he wasn’t satisfied…and mulled over his station in life. It was, he knew, of singular dimension: money.” Carnegie wrote in his autobiography, “The amassing of wealth is one of the worst species of idolatry.” He wanted a life “more elevating in character.” He would “push inordinately” for the next two years, and then “spend the surplus [income] for benevolent purposes.” It was the earliest manifestation of his philanthropic impulse. He vowed to “resign business at thirty-five.”

Carnegie would follow his instincts, but not on that timetable. At 35 he was a millionaire, still striving in pursuit of another business that intrigued him—a form of “malleable iron” known as steel. In 1872 Carnegie visited Henry Bessemer’s steel plant in Sheffield, England. Later that year he and William Coleman, his oil business partner, bought land in Braddock, Pa., outside Pittsburgh, and with a handful of other investors built a state-of-the-art Bessemer-type steel factory. Carnegie was the largest shareholder. Eight steel companies were already operating in the United States at the time, including two in Pennsylvania partially owned by the Pennsylvania Railroad, but Carnegie was unfazed. Congress had slapped a $28-a-ton tariff on imported steel, which destroyed the competitiveness of British producers. Carnegie wrote a fawning letter to J. Edgar Tomson, his former railroad boss, and asked to name his steel factory after him. Tomson agreed. It was largely a ploy to ensure that the Pennsylvania Railroad would give a portion of its rail business to Carnegie’s new enterprise. It did.

The Edgar Thomson Steel Works turned out its first steel rails and ingots in 1875, and it quickly became a major player in the industry. Carnegie was obsessed with productivity and efficiency—getting the lowest prices for the limestone, coke and iron ore with which steel was made, along with the lowest rates for freight transport and labor. Carnegie made the best steel and yet sold it at prices below the competition. He bought his coke from Henry Clay Frick, who owned a growing empire of coke fields and ovens not far from Braddock and who became chairman of Carnegie’s steel operation in 1889. Characteristically, Carnegie bought 11 percent of H.C. Frick Company in 1882 and by 1888 owned a controlling interest.

Despite his industrious youth and the onerous demands he made of his workforce, Carnegie worked very little after making his first fortune. From his mid-30s to his retirement, he spent only a few hours in the morning supervising his steel enterprise, typically by telegram and letter from hotels and his home. He indulged his fondness for travel and passion for writing. He chronicled his social, political and cultural observations in eight books, and seldom missed an opportunity to heap praise on American republicanism and institutions and ladle scorn on England’s antiquated political and economic values, thus earning the nickname the Star-Spangled Scotsman. His most notable book, Triumphant Democracy, is a glossy, well-researched paean to America. He writes in the preface: “The old nations of the earth creep on at a snail’s pace, the Republic thunders past with the roar of an express.” It was a bestseller.

When in his 40s, the wealthy bachelor started seeing Louise Whitfield, 21 years his junior. The two had a tortured courtship, mostly because Carnegie didn’t think his mother would approve. After his mother died, Carnegie, age 51, married Louise in 1886. The couple had one daughter, Margaret, and spent nearly six months a year in Europe, settling every summer in the Scottish Highlands, eventually at Carnegie’s own castle called Skibo. Meanwhile, the businessman assiduously cultivated relations with important people—among them Samuel Clemens (who thought Carnegie was vain and “talked too much”), U.S. secretary of state James G. Blaine and two celebrated English men of letters—Matthew Arnold and John Morley. With Morley’s help, Carnegie met his intellectual hero, Herbert Spencer.

Before becoming infatuated with Spencer’s philosophy, Carnegie had flirted with socialism and professed his solidarity with working men and unions. He once wrote that the right of workers to organize and form trade unions was “no less sacred than the right of manufacturers to enter into associations,” and he declared that he would never replace union workers with non-union workers. But as Edgar Thomson plant superintendent “Captain” William Jones once acknowledged, Carnegie was a “sidestepper,” meaning slippery when it came to matching his actions with his words. Labor newspapers gave him the benefit of the doubt for a few years, even as he was trimming wages. But that stopped when the pay fell as productivity and profits soared, when factory shifts were extended from eight to 12 hours and when Frick, with Carnegie’s approval, broke the union at Edgar Thomson in 1889.

Breaking unions was a nasty business but eminently justifiable to a Spencer acolyte. As Carnegie asserted in The Gospel of Wealth, economic inequality was the “great price” that must be paid for economic progress. The important thing was that the high tide of industrialization was lifting all boats. Carnegie coined a motto to reinforce that message: “All is well since all grows better.” All was better because “the poor [now] enjoy what the rich could not before afford. What were the luxuries have become the necessaries.”

All was better, in his view, because of the talent of industrialists like him. “Not evil but good has come to the race from the accumulation of wealth by those who have the ability and energy to produce it,” wrote Carnegie. “It is well, nay, essential, for the progress of the race that the houses of some should be homes for…all the refinements of civilization, rather than none should be so. Much better this great irregularity than universal squalor.” The law of competition, he argued, demands the “strictest economies, among which the rates paid to labor figure prominently, and often there is friction between the employer and the employed, between capital and labor, between rich and poor. While the law is sometimes hard for the individual, it is best for the race, because it ensures the survival of the fittest in every department. We accept and welcome therefore…great inequality of environment, the concentration of business, industrial and commercial in the hands of the few.”

Carnegie opposed “indiscriminate charity”—simply giving money to needy people—because it might reward vice. Better to create public endowments and public institutions of culture and learning. In the ideal state of individualism, “the surplus wealth of the few will become, in the best sense, the property of the many, because administered for the common good, and this wealth, passing through the hands of the few, can be made a much more potent force for the elevation of our race than if it had been distributed in small sums to the people themselves. In bestowing charity, the main consideration should be to help those who will help themselves.” But the tycoon closed his essay with an ominous warning for his wealthy associates: “The man who dies leaving behind many millions of available wealth, which was his to administer during life, will pass ‘unwept, unhonored and unsung.’ . . . The public verdict will then be: ‘The man [who] dies thus rich dies disgraced.’ ”

Carnegie may have been “indifferent to the living welfare of his employees,” as Dreiser would charge, but he did not die with his money. He built libraries at all his steel plants, and in 1895, three years after Homestead, he gave $5 million to Pittsburgh to build a complex that included a library, music hall and subsequently a lavish art gallery and museum of natural history. The Carnegie Institute took years to complete and cost Carnegie about $25 million, including a $6 million endowment. At the dedication ceremony for the art gallery and natural history museum, according to Peter Krass, Carnegie was overwhelmed by the grandeur of the complex, saying to his wife: “It is like the mansion raised in the night by the genie, who obeyed Aladdin.” Louise replied, “Yes, and you did not even have to rub the lamp.”

After the sale of his company and his retirement in 1901, Carnegie buckled down to the business of philanthropy. With $226 million in gold bonds, earning more than $15 million a year in interest, he was the second richest man in the world (behind John D. Rockefeller). His first retirement bequest was a $4 million relief fund to assist employees injured at his steel company and to provide pensions to dependents of those killed. Carnegie had a special fondness for the institution by which he’d educated himself and next gave $5.2 million to the New York Public Library to establish a 65-branch network. For years thereafter he made donations to establish public libraries in cities around the world, though all were required to raise money to remain self-sustaining. When a city requested a library, his assistants analyzed information about the city’s population, tax revenue and potential sites before making a decision. The answer was usually yes. Carnegie funded public libraries for 500 cities from 1900 to 1903. “I’m in the library manufacturing business,” he quipped. Ultimately, Carnegie’s 1,400 library grants in America totaled about $41 million, and 660 library grants in Britain and Ireland totaled another $15 million—in total worth billions today.

Carnegie was just getting started. He gave $10 million to start the Carnegie Scottish Universities Trust, and then created the Carnegie Institution in Washington, a center for pure scientific research, with a $10 million grant that was later more than doubled. He next created a “hero fund” for private individuals who performed heroically in any walk of life or who were engaged in “peaceful vocations.” He called this fund—which gave $27 million in cash, pensions, scholarships or fellowships to 9,000 heroes or their dependents from 1904 to 2004—“my pet child” because it was his original idea. In 1905 he funded a pension system for retiring teachers at universities and technical schools. So many teachers flocked to colleges associated with the Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching that Carnegie biographer Joseph Wall noted, “By 1909 the foundation had become the unofficial accrediting agency for colleges and universities.” Recognizing that it could not pay pensions for every college professor in America, the foundation’s trustees created a contributory pension plan known as the Teachers’ Insurance and Annuity Association, which still exists as TIAA-CREF.

Carnegie spent the last 25 years of his life working fanatically to end imperialism, military arms buildups and the threat of war. He wrote a string of letters to President William McKinley to dissuade him from annexing the Philippines after the Spanish-American War—even reportedly offering $20 million to buy that country’s independence. He lobbied Presidents Theodore Roosevelt and William Howard Taft to craft conflict arbitration treaties with other major powers. Roosevelt humored the tycoon but viewed him otherwise as a naive and meddling hypocrite. “The same little capitalist who urged presidents to do right things in Philippines, Panama and international diplomacy had never done the right or moral thing as a businessman,” TR wrote to a friend. Taft, on the other hand, supported the idea of arbitration treaties. Aiming to further motivate Taft, Carnegie spent $10 million to found the Carnegie Endowment for Peace. Some pundits scoffed, but many called the peace endowment Carnegie’s greatest gift. The State Department drafted arbitration treaties with Britain and France that were signed by Taft and his European counterparts, prompting Carnegie to declare, “I am the happiest mortal alive.” But Roosevelt lobbied against the treaties and the Senate failed to ratify them, and Carnegie was left feeling bitter and betrayed.

The outbreak of World War I and its abject brutality shocked Carnegie, pushing him into a serious depression. In his late 70s, his influence waned. He’d spent $25 million to promote peace, he’d been prescient about the risks—and now millions of men were getting slaughtered. He appealed to fellow pacifist President Woodrow Wilson to declare war on an “insane” Germany. By the time Wilson did in 1917, Carnegie was in failing health. He would die in 1919, at age 83.

As Krass recounts, Carnegie paid his last visit to his steel works in 1914. He appeared at a ceremony to mark the 25th anniversary of the Braddock (Edgar Thomson) Carnegie Library. “I’m willing to put this library and institution against any other form of benevolence,” Carnegie boasted to the crowd. “It’s the best kind of philanthropy.” Then, invoking his favorite motto, he added: “This is a grand old world and it’s always growing better. And all’s well since it is growing better, and when I go on trial for the things done on earth, I think I’ll get a verdict of ‘not guilty’ through my efforts to make the earth a little better than I found it.” Why did the tycoon invoke the idea of “guilt”? In Krass’ view, it was because Carnegie “suspected that he had exacted too high a price from his laborers, and the visit to Braddock reminded him of it.”

Today U.S. Steel, the firm J.P. Morgan formed from Carnegie Steel, remains America’s steel standard-bearer, and much of its product still comes from the Edgar Thomson Works at Braddock Fields, the locus of Carnegie’s steel business more than a century ago. It, along with the many libraries and benevolent foundations, are the legacy of a complicated capitalist—a self-made man who always thought big.

Originally published in the February 2015 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.