An internet sleuth who describes himself as just a “person off the street” has made a discovery that could possibly push the timeline of written language back by tens of thousands of years, according to a study published Thursday in the Cambridge Archeological Journal.

Ben Bacon, a furniture conservator based in London, U.K., was recently admiring European cave paintings of animals and other figures posted online that had been etched some 15,000 and 40,000 years ago during the Paleolithic Age when an idea struck him.

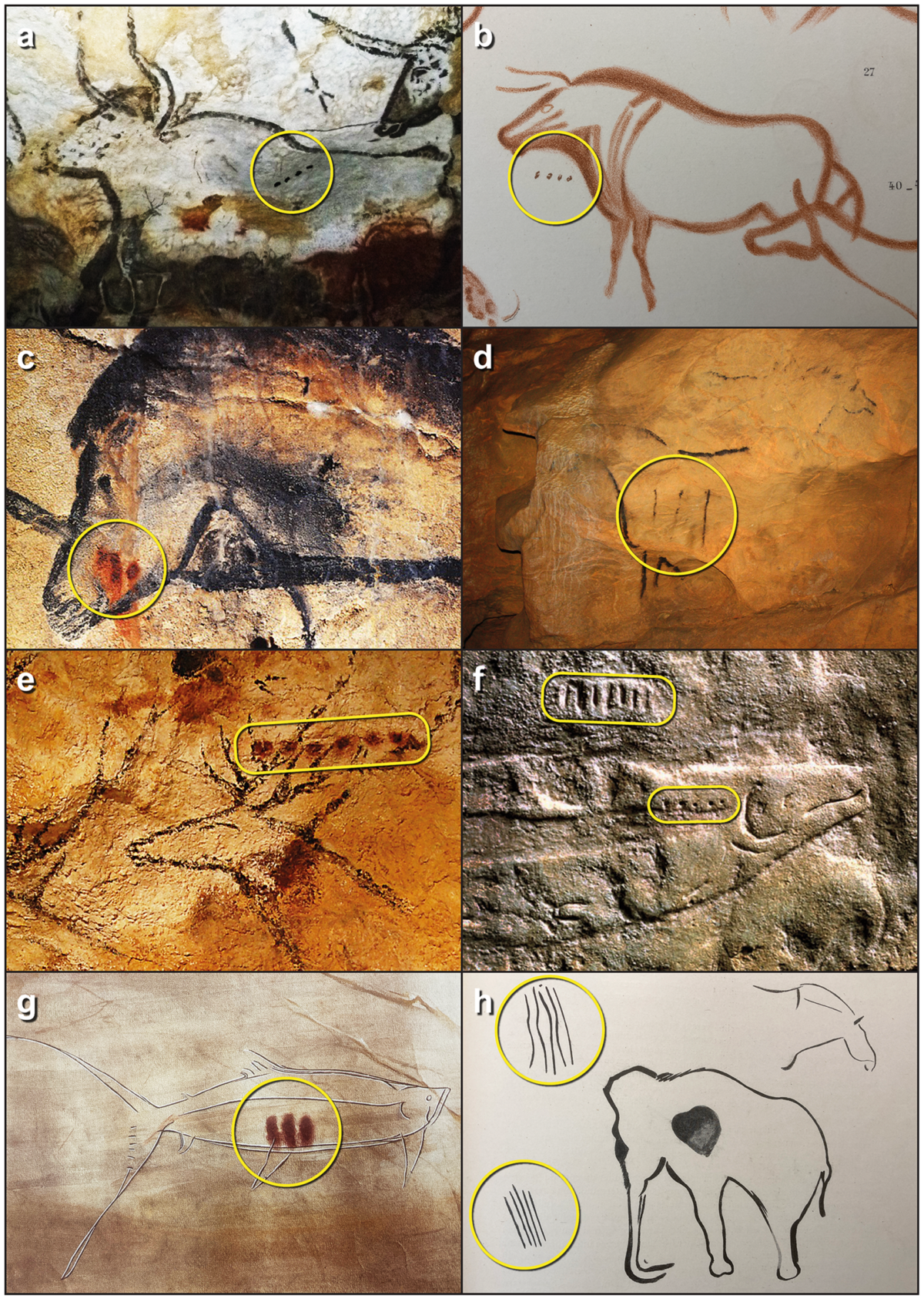

The cave paintings include markings of dots and lines, which have evaded archeological explanation for decades, Vice reports.

But according to Bacon, “the first known writing in the history of Homo sapiens,” came in the form of a prehistoric lunar calendar.

“I think that the cave paintings fascinate us all because of their beauty and visceral immediacy,” Bacon told Motherboard in an email. “I was idly looking at Palaeolithic paintings one night on the Web and noticed, purely by chance, that a large number of animals had what I took to be numbers associated with them.”

Excited about his hypothesis, Bacon enlisted archaeologists from Durham University and the University College London to help codify his theory.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Wednesday.

Bacon set out to decode the markings, focusing on the lines, dots, and Y-shaped symbols that appear in hundreds of the cave paintings.

Since the paintings were discovered 150 years ago, some researchers had previously posited that the numerical notation was “designed to count the number of animals sighted or killed by these prehistoric artists,” Vice wrote. “Bacon made the leap to suggest that they form a calendar system designed to track the life cycles of animals depicted in the paintings.”

Apparently, all it took to decipher the meaning of the mysterious etchings was some fresh eyes.

“It seems to us unnecessary to need to convey information about the numbers of individual animals, the times they have been sighted, or the number of successful kills,” the researchers noted as their premise for their departure in thought.

“It seems far more likely that information pertinent to predicting their migratory movements and periods of aggregation, i.e. mating and birthing when they are predictably located in some number and relatively vulnerable, would be of greatest importance for survival,” they added.

Bacon notes that the paintings never exceeded 13 lines and dots, which would add to his theory of a lunar calendar.

“It follows that knowledge of the timing of migrations, mating and birthing would be a central concern to Upper Palaeolithic behaviour, the distribution and timing of which was fully dependent upon these resources,” the researchers wrote.

It would then make sense that the lunar calendar was not tracking time in terms of years, but the seasons optimal for survival.

Researchers tested their theory by compiling a database of more than 600 line-and-dot sequences without the Y symbol, as well as some 250 sequences with the Y. They explored “whether the number of markings and the position of <Y> in sequences was random or ordered.”

Their hypothesis held up.

And although the team anticipates arguments and blowback from their seemingly staggering findings, the discovery, Bacon told Motherboard, shows that our Paleolithic ancestors “were almost certainly as cognitively advanced as we are” and “that they are fully modern humans.”

“Their society achieved great art, use of numbers, and writing,” he said, and “reading more of their writing system may allow us to gain an insight into their beliefs and cultural values.”

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.