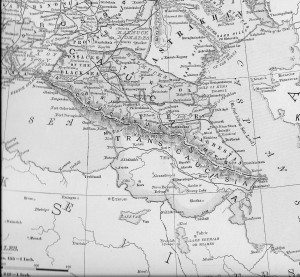

The Great War’s Caucasus Front did not deserve the name of sideshow. Although for the untrained eye there were no objectives there that would cripple either the vast Russian or the Ottoman Empires. Its rocky crags reached heights of 4,000 meters in many places and winter temperatures often dropped to minus 30 degrees Celsius. There were few roads that were beyond the width of goat trails. It was an inhospitable place in which to fight a war. Yet beneath this deceiving plaster façade, military leaders on both sides saw things differently. General of the Infantry Nikolai Iudenich, Russian Chief of Staff for the area, saw the conquest of the Caucasus Front as an opportunity to establish Russian authority all along the Black Sea coast with the ultimate goal of capturing Constantinople. Possession of the area would also secure the Persian oil fields just on the other side of the frontier. Enver Pasha, the Ottoman Empire’s war minister and chief of the army’s general staff, saw the front as a theater for showing his military prowess as well as a way of tying down tsarist forces that might be shipped to Galicia or Poland to fight his allies, Germany and Austria-Hungary. He also envisioned a pan-Turkic empire stretching from the Anatolian Plains to Afghanistan of which he would be the ruler. The key to both their dreams lay in the Turkish fortress at Erzerum.

Erzerum had been a strategic position since the 4th century AD when the Byzantine Empire had seized it from the Persians during the partition of Armenia. Throughout the Middle Ages, the city served as a staging area for repeated attempts to conquer Constantinople. After the fall of the Eastern Roman Empire, the city sank into obscurity until the early 19th century as both the Russian and Ottoman Empires began establishing their power over the Caucasus region. Twice the Russians took Erzerum only to have to return it as part of the peace treaties. After its return following the Russo-Turkish War of 1877-1878, the Ottoman Empire administrators decided that the city was an invaluable asset in the defense against an ever expanding Russian Empire. The Sultan commissioned British army engineers to modernize its defenses in light of innovations in artillery and siege techniques. The engineers began by moving the primary defenses away from the city and placing them into outer works on the road leading to Hasankale, a town half the distance to a newly established Russian frontier. In 1890, German engineers replaced the British. Over the next 24 years these engineers added modern features. Twenty forts were established along the valleys leading from Erzerum to the Russian border. Sixteen of the forts were echeloned in three lines on the Hasankale – Köprüköy road with two flanking groups of two forts each. The flanking forts were 12 kilometers to the north and five kilometers to the south. The city, ringed by trenches reinforced with barbed wire entanglements, was the last point of defense. Within the complex were 235 artillery pieces ranging in calibers from 75mm to 155mm of which 100 were mobile quick firing Krupp cannons that could be moved to selected points to augment those pieces that were in permanent works.

At the beginning of the Great War in 1914, Erzerum was the headquarters for the Turkish Third Army. In the early days of the war, the fortress complex had served as the staging area for two abortive attempts to invade Russia. Each of the incursions had resulted in devastating casualties for the 3rd Army in both men and equipment of which neither could be replaced because of needs along the Suez front and at Gallipoli. Battalions of the IX, X, and XI Corps were at 2/3 their normal strength. These meager resources, approximately 65,000 soldiers supported by 188 artillery pieces, were stationed along a front 60 kilometers in front of the fortress. Third Army’s commander Mahmut Kamil Paşa along with his German chief of staff concentrated their soldiers in heavily fortified strong points that depended on terrain as obstacles to any attack rather than building a continuous trench network. This concept stretched their meager resources of men and material over a much longer front. However, the defense plan presented drawbacks because of the reliance on terrain. There were numerous gaps in the line and many of the posts were isolated from support by adjacent positions because of intervening chasms, mountains, or ravines. Such drawbacks were lamentable but not unanticipated. Mahut Kamil Paşa probably recognized that a resourceful enemy could take on portions of the line in detail or maneuver between units to outflank and bypass them. Quite possibly, he may have seen these scattered positions as his first defense line that was not meant to be held for any length of time. Instead, as the line deteriorated, the men would fall back on the fortress complex where there were an additional 74,000 soldiers and heavier artillery that would put up a stiffer defense.

At the beginning of the Great War in 1914, Erzerum was the headquarters for the Turkish Third Army. In the early days of the war, the fortress complex had served as the staging area for two abortive attempts to invade Russia. Each of the incursions had resulted in devastating casualties for the 3rd Army in both men and equipment of which neither could be replaced because of needs along the Suez front and at Gallipoli. Battalions of the IX, X, and XI Corps were at 2/3 their normal strength. These meager resources, approximately 65,000 soldiers supported by 188 artillery pieces, were stationed along a front 60 kilometers in front of the fortress. Third Army’s commander Mahmut Kamil Paşa along with his German chief of staff concentrated their soldiers in heavily fortified strong points that depended on terrain as obstacles to any attack rather than building a continuous trench network. This concept stretched their meager resources of men and material over a much longer front. However, the defense plan presented drawbacks because of the reliance on terrain. There were numerous gaps in the line and many of the posts were isolated from support by adjacent positions because of intervening chasms, mountains, or ravines. Such drawbacks were lamentable but not unanticipated. Mahut Kamil Paşa probably recognized that a resourceful enemy could take on portions of the line in detail or maneuver between units to outflank and bypass them. Quite possibly, he may have seen these scattered positions as his first defense line that was not meant to be held for any length of time. Instead, as the line deteriorated, the men would fall back on the fortress complex where there were an additional 74,000 soldiers and heavier artillery that would put up a stiffer defense.

On the other side of the line was approximately 325,000 Russian soldiers nominally commanded by Grand Duke Nikolay Nikolayevich assisted by General of the Infantry Nikolai Iudenich as his chief of staff. Although the Grand Duke had started the war as commander in chief of the Russian forces along the entire Polish and Galician fronts, the tsar had relieved him of the command after his failure to stop the Central Powers’ advances in Poland. Instated as the military governor of the Caucasus region, Nikolay Nikolayevich relied heavily on the planning ability of his chief of staff who had been at the post since 1913 and in the region since 1907. Prior to the Grand Duke’s arrival, Iudenich had successfully coordinated the defense of the Caucasus twice.

Iudenich had entered the army at 17. Noted for his intellect early in his career, he had spent the majority of his years on the general staff. He managed to secure command of a regiment during the Russo-Japanese War where his superiors noted his ability to lead from the front with success. His reckless attitude during the war led to him being wounded and evacuated but not without promotion and recognition by the tsar. In 1907 he became the deputy chief of staff for the Caucasus. Six years later he became the chief of staff. Saddled with incompetent superiors appointed to their positions by the Tsar for favors given and to reward long service rather than military merit, Iudenich fended off very strong Turkish invasions of the region in October and December 1914 because of his long term knowledge of the region and very competent use of reserves. Throughout 1915 the front had remained relatively quiet. Both Turkish and Russian strategic interests were in different areas. But the solitude was shaken by two factors in late 1915.

The first factor was internal. As a result of the losses in Poland and Galicia, the Russian general staff began siphoning off units from the Caucasus front which they considered unimportant. By November 1915 they had taken 43 battalions, or roughly 43,000 men, from Iudenich and replaced them with only two cavalry brigades, about half the number lost. To replace the losses, Iudenich had reduced the manpower in existing divisions to make up 17 new rifle battalions. He had also called for a third mobilization in the Cossack regions. This had provided an additional 10 cavalry battalions. Iudenich drew another 100,000 men from the local militia units to fill out the ranks thinned by battles and a cholera epidemic. Iudenich knew that this numeric advantage opposite his enemy would not last. Already, the Russian general staff was planning a summer offensive in Galicia and for it Iudenich expected that they would take more units away from his front. If his area would remain quiet and on the defensive behind strong positions, the additional loss of manpower would not be a hindrance; however, there was another factor that changed his state of affairs.

In early December, the general staff notified Iudenich that the Allies were going to evacuate the Gallipoli peninsula. The campaign to capture Constantinople had failed to get off the beaches. The withdrawal would free 20 Turkish infantry divisions. Although casualties among those divisions had been high and many of the losses had not been replaced, the soldiers who were left were battle hardened and possessed the highest morale that came from defeating their French and British opponents. Iudenich had little doubt that the Turkish general staff would couple some of the divisions with the sturdy 3rd Army veterans and mount another offensive in his direction. Those soldiers would easily out match the militias and newly conscripted soldiers he relied on for the defense of the present line. A withdrawal to the old frontier where his front would be shortened and his lines of communication and supply to Tiflis reduced was not a viable plan. His forces would be fragmented and candidates for defeat in detail. Iudenich’s staff instead formulated a plan for an attack on the Erzerum fortress complex. Its capture would remove a concentration point for an invasion and give the Russians a strong defense line against any future invasion attempts. The only drawback to the plan was that the action would have to be done in the dead of winter at high altitudes. This timing was necessary because of the impending culling of Iudenich’s divisions by the general staff and the anticipated arrival of the Turkish divisions from Gallipoli.

In December, Iudenich’s staff began to plan the minutia for a winter offensive to begin the following month. Strategically, the offensive was a preemptive strike to preclude a Turkish spring offensive. Tactically, it was to create a buffer of territory on Turkish soil and remove the Erzerum fortress complex as a place for massing and launching future invasions. A force of 100,000 soldiers and 340 artillery pieces would carry out a two phased plan. Phase one was to breach and reduce the number of defending soldiers at Köprüköy, 60 kilometers before Erzerum, by outflanking it and capturing the majority of soldiers there. This would be followed by phase two: the capture of Erzerum. Iudenich had little doubt that his soldiers could meet the challenge of an attack. What he was most worried about was the time both phases would take.

Iudenich and his staff expected that the divisions engaged at Gallipoli would not be immediately available for redeployment to the Caucasus. They would need reorganization and refitting. However, when the Turkish generals in Constantinople learned that he had begun an offensive toward Erzerum, they would send reinforcements as soon as possible. His staff estimated that it would take two months for them to travel from the Gallipoli area to Erzerum. Such a delay was caused by the lack of railways in Turkey. Only two railroads ran out of the Constantinople area. One went as far as Ankara. From there the soldiers had to march 800 kilometers to Erzerum. Another track ran to Ras el Arim. This route was not direct. There was no tunnel as yet through the Taurus Mountains. The Turkish soldiers would have to march for a day through the mountains before they could continue the rail trip to the end of the line. At Ras el Arim they would detrain and have to march an additional 400 kilometers to the fortress. The marches would be long and tedious, encumbered by a reliance on animal powered transportation for equipment. The vast Turkish army possessed few motor transports. The Russians would have to take and strengthen Erzerum before the reinforcements arrived.

ATTACKING THE TURKISH LINE

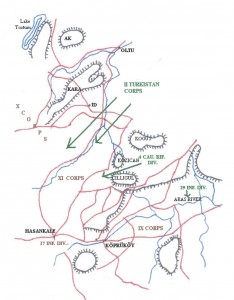

A Caucasus winter is an inhumane season that causes humans and animals to seek shelter and inactivity. Temperatures among the 4000-meter-high peaks often drop to – 30 degrees Celsius and snow falls in meters often swirling into cyclones that rival the force of a Saharan sandstorm. A person’s senses become muddled by these conditions. Simple finger movements become increasingly difficult with the passing of time when not sheltered and with that ability gone, a person loses the capability to pull a rifle’s or pistol’s trigger. In those circumstances the most effective tactic to win battles is tightly packed infantry in bayonet attacks. Iudenich knew that such tight formations were perfect targets for artillery. The high casualties that would undoubtedly arise through these tactics could not be tolerated considering the theater’s low priority in receiving replacements, the quality of the ranks, and a need to meet a timetable. To reduce the drain of soldiers, Iudenich devised a three-part plan to breach the Turkish line by way of the unoccupied Kozican and Cilligül ridges.

The offensive was to begin on January 10 when the II Turkistan Corps would demonstrate for two days along the northern part of the front from Lake Tortum to the northern edge of Kosican. The demonstration was to give the impression of being a main thrust and draw off Turkish reserves. On 12 January and also lasting for two days, the I Caucasian Corps’ 39 Infantry Division was to attack along both sides of the Aras River, towards Köprüköy. That attack was designed to draw off any remaining reserves not committed to the Turkistan Corps’ assault. While these two deceptions were going on, the 4th Caucasian Rifle Division supported by two reserve regiments would climb Cilligül with the intention of capturing its shoulders by 15 January. They would then descend down the slope and come up behind the Turkish line cutting off the retreat route to Erzerum. The plan relied on surprise to be successful.

The offensive was to begin on January 10 when the II Turkistan Corps would demonstrate for two days along the northern part of the front from Lake Tortum to the northern edge of Kosican. The demonstration was to give the impression of being a main thrust and draw off Turkish reserves. On 12 January and also lasting for two days, the I Caucasian Corps’ 39 Infantry Division was to attack along both sides of the Aras River, towards Köprüköy. That attack was designed to draw off any remaining reserves not committed to the Turkistan Corps’ assault. While these two deceptions were going on, the 4th Caucasian Rifle Division supported by two reserve regiments would climb Cilligül with the intention of capturing its shoulders by 15 January. They would then descend down the slope and come up behind the Turkish line cutting off the retreat route to Erzerum. The plan relied on surprise to be successful.

Iudenich and his staff went through great lengths to insure secrecy. Materiel to support the mid-winter operation was built up slowly and it was easily confused by what spies might think to be preparation for the winter. Soldiers were issued short fur coats, trousers lined with cotton-wool, felt boots, thick shirts, gloves, and fur caps that covered head and ears. They were also given two small logs of wood and ordered to load them in their packs. To give a picture of serenity that normally accompanied late December, officers and soldiers along the frontier were encouraged to send representatives to Tiflis to buy items for the upcoming Christmas season. Another effort to mask the offensive was the relocation of the 13th Caucasian Rifle Division and its support just five days before the attack was to begin. Its entraining was done in daylight so that Turkish spies could report the movement.

The deception was effective. The Turkish 3rd Army commander departed on leave for Constantinople and his German chief of staff went to Germany to recuperate from his bout with typhus. They left behind what they thought to be a well positioned line. On the north, X Corps’ three divisions covered 45 kilometers from Lake Tortum to the Kozican ridge. The ridge itself was under the control of XI Corps’ 34th Division; however, this unit was separated from the rest of XI Corps’ 33rd and 18th Divisions that controlled the 23 kilometers from Cilligül to the Aras River by the unoccupied summit. The final 26 kilometers from the Aras to Dram-dag was manned by IX Corps’ 28th and 29th Divisions plus detached units of the 37th Infantry Division. IX Corps’ 17th Division was held in army reserve near Hasankale. The only drawback to the deployments was the lack of corps reserves. Third Army had ordered each corps to designate their own reserve. Because of such reduced manning levels, each corps could only set aside a regiment each. Considering that most battalions had approximately 600 men, as opposed to the normal 1000, the corps reserve was only 1200 men. Russian battalions were near their full strength of 800-1000. But numbers were not the only key to the defenses.

The Turkish Aras River defense line was the best prepared for defense. Preceding two trench lines were extensive wire entanglements and the majority of the artillery was concentrated into groups on both sides of the river. Three groups of guns were on the slopes north of Haran with another two groups on the uphill side of Tyk-dag near Endek. The artillery could provide enfilade fire all along the Aras valley. In X Corps’ area along the Oltu – Hasankale road, trenches had been blasted into the rock and the debris heaped on both sides to form two towers into which were mounted machine guns and two mountain guns.

The attack began on schedule and came as a complete surprise. After a short bombardment, the II Turkistan Corps moved against the X Corps. The fire from the two towers and the stone trenches was murderous. Within a few hours, the Russians suffered 700 casualties but, unaware of their role of being a diversion, the soldiers pressed on. X Corps committed their reserve regiment.

Phase two began on schedule two days later. Once again, the Russians charged ahead without taking into consideration their role as a feint. Casualties there too were high. Turkish machine guns stopped any appreciable advance but the élan shown by the Russians convinced the Turks that this was the main thrust. Not only was the corps’ reserve committed, 3rd Army sent the 17th Division forward from Hasankale. These units were thrown into a counter-attack on 13 January.

While the fighting of the first two phases was going on, the 4th Caucasians began climbing the shoulders of Cilligül in a raging snowstorm. Soldiers had to dig paths through two meters of snow but by 15 January, they had moved off the heights at Serbogan and Pazarçor outflanking the Turkish 17th and 33rd Infantry Divisions who still held the line against the zealous Russian 39th.

The Turks became aware of the outflanking movement and began to evacuate the line. The retreat was orderly and active. Iudenich got neither a rout nor envelopment. The chief cause of missing this opportunity was the utter exhaustion of the 4th Caucasians and the heavy casualties incurred by the 39th Division. The Turkish units fell back on the Erzerum fortress complex unpursued having lost 15,000 killed, wounded, or frozen, and 5000 as prisoners. A further example of a missed opportunity was that only 30 Turkish cannons out of 188 that were on the line were captured. A four battalion strong rearguard assisted by two guns at Hasankale covered the withdrawal. They were finally overcome by mounted Siberian Cossacks attacking in their avalanche formation. One thousand Turks were sabered while 1500 surrendered. The overall strategic plan’s phase one ended on 19 January when Cossack horse batteries opened fire on the outer Erzerum forts.

ERZERUM, MORE PLASTER THAN CONCRETE

Iudenich would have been surprised at the Turkish general staff’s reaction to the breaching of the Caucasus front. There was no gnashing of teeth or shouts to orderlies to take down orders that had to be executed in all haste. The staff reacted as if they were sedated. Perhaps the word euphoria would better describe their response. The victory over the French and British forces on Gallipoli was a cause for celebration. To their view the 20,000 or so casualties suffered at Köprüköy was a drop in the bucket compared with the sky high rate experienced in Gallipoli. Besides, they would have mused, Erzerum will stand impervious to assault. Additionally, the staff believed that the Russians were too exhausted to do anything more until spring. There was no need, they went on to say, to immediately dispatch any reinforcements from those divisions freed from Gallipoli. The staff split the available divisions among the three active fronts with the majority of the units going to Palestine and Mesopotamia. Both those fronts appeared to be more important. In Mesopotamia, the British were forcing their way up the Euphrates toward Baghdad at an alarming rate and in Palestine, there was a need for defense since the British and French soldiers who had evacuated Gallipoli would probably be repositioned there. The staff allocated seven divisions to the Caucasus but delayed their departure until February.

At his headquarters in Kars, Iudenich sat nervously awaiting reports from spies that Turkish reinforcements were making their way to the fortress but no such news came. From 20 January to 10 February, the Russians consolidated their gain and brought up most to their artillery. Regrettably, the cannons were not of the heavy calibers that would be needed to take on concrete emplacements. The Russian army had allowed their reserves of heavy artillery to thin itself out over the last 10 years before the war until there were few such howitzers left and shells were even scarcer. Iudenich’s artillery consisted mostly of 75mm and 155mm guns. They couldn’t reach into the trenches or emplacements. Iudenich would have to again rely on the infantry to take the forts of Erzerum.

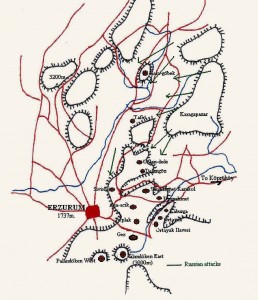

Iudenich had known the Turkish disposition on their defensive line and planned his attack based on solid intelligence. Although he knew the position of every fort in the Erzerum complex, he was unaware of how the survivors of the previous battle had placed themselves. Consequently, he adopted a plan that probed the fortress line until a weakness was revealed. To the north, he ordered the II Turkistan Corps to move against Fort Kara-Göbek. The fort was isolated from the others. Five kilometers separated it from Fort Tafet to its south. The remains of X Corps supported this fort. In the center of the line, Iudenich ordered the 4th Caucasian Rifle Division to scale the rocky, 3500-meter-high ridge of Kargapazar bypassing the majority of X Corps to come down behind Fort Kara-Göbek and to the north of Fort Tafet. Once there, they would link with the II Turkistan Corps for an assault on the city itself thus outflanking all the other forts. In the south, the general ordered the 39th Division of the I Caucasian Corps to assault Forts Çoban-dede and Dalangöz. This area was supported by the Turkish IX Corps which had suffered nearly 70% losses in the previous battle. To protect against the Russian attack they knew would eventually come, the IX Corps soldiers had constructed trenches in the deep snow before the forts. The soldiers had poured water on the slopes leading to the snow trenches to make any assaults difficult.

The general advance began on 10 February. The II Turkistan Corps succeeded in surprising the defenders of Kara-göbek. The fort was surrounded on the first day and subjected to an artillery barrage. In the center of the line, the 4th Caucasians ascended the slopes of Kargapazar reaching the top that evening but not without difficulty. The snow proved to be so deep that the artillery had to be taken apart and moved piecemeal. Then there was the cold. Temperatures were many degrees below zero. It was fortunate that Iudenich had foreseen these difficulties earlier and had ordered the soldiers to carry two wood logs in their packs. The logs built much needed fires to weather the night. Nevertheless, nearly 1000 froze to death while another 1000 suffered from serious frostbite. Finally, on 14 February, the 4th Caucasians began their descent. They had outflanked the X Corps, Kara-göbek, Tafet and were in support of the Turkistan Corps.

The general advance began on 10 February. The II Turkistan Corps succeeded in surprising the defenders of Kara-göbek. The fort was surrounded on the first day and subjected to an artillery barrage. In the center of the line, the 4th Caucasians ascended the slopes of Kargapazar reaching the top that evening but not without difficulty. The snow proved to be so deep that the artillery had to be taken apart and moved piecemeal. Then there was the cold. Temperatures were many degrees below zero. It was fortunate that Iudenich had foreseen these difficulties earlier and had ordered the soldiers to carry two wood logs in their packs. The logs built much needed fires to weather the night. Nevertheless, nearly 1000 froze to death while another 1000 suffered from serious frostbite. Finally, on 14 February, the 4th Caucasians began their descent. They had outflanked the X Corps, Kara-göbek, Tafet and were in support of the Turkistan Corps.

The assault on the southern forts was even more spectacular. During the night of 12 February, the 39th Division, dressed in white coats, stealthily crawled toward Forts Çoban-dede and Dalangöz. They managed to get within 80 meters of the two forts when an alert sentry ordered the forts’ searchlights turned on. The lights showed the Russians as surreal images but the defenders quickly roused themselves and opened a deadly machine gun barrage killing or wounding nearly one third of the division. The 156th Yelizavetpolski Regiment pushed on until it was below the fire cone of Çoban-dede but they were unable to take the fort. A counterattack by the Turkish 108th Regiment forced a brief retreat before it was repelled but the fort remained active.

On the left, the 153rd Bakinski Regiment captured Fort Dalangöz; however, the failure of the Yelizavetpolski Regiment and the Turkish counterattack put them in grave jeopardy. Cannon fire from Çoban-dede and Uzunahmet Karako fell on Dalangöz. The Bakinski Regiment was nearly cut off but managed to hold the fort. Late on 13 February, the Russians sent forward the Derbentski Regiment to reinforce the Bakinski Regiment. They advanced on their coats which they stretched across the deep snow. When they finally reached the fort they were greeted by 300 still active assaulters. The 153rd had suffered 1100 casualties in holding the works.

On 14 February, the 4th Caucasians and the II Turkistan Corps linked up on the south of a captured Kara-göbek and began an advance on Tafet. Outflanked, the Turks evacuated Tafet and pulled back. On the 15th, Forts Kaburga, Ortayuk, Uzunahmet- Karakol and Sivishli were blown up and Çoban-dede was evacuated. Russian soldiers entered the city on the following day. However, once again the exhaustion of the Russians did not permit a hot pursuit which began the following day and terminated at Mamahatun on 13 March. Communication and supply lines were extended as far as they could go.

Turkish losses at Erzerum were placed at 10,000 killed and wounded with 5000 as prisoners. Their losses continued to mount during the pursuit due primarily to desertions; however, rearguards were stubborn enough to make a difference slowing the Russians. Material wise, the Russians secured the artillery of the two corps and the fortress. Russian losses in taking the fortress included 1000 killed, 4000 wounded, and 4000 lost to frostbite. These figures added to overall casualties since the operation began on 10 January brought the toll to 17,000. Nevertheless, Iudenich had met his tactical objective of capturing the fortress in less than 60 days. Now he needed to hold on to the buffer zone he had acquired.

AFTERMATH

News of the fortress’s fall reached Constantinople almost immediately. Enver Pasha and his general staff were panicked. This time, orderlies ran about with orders to corps and divisions to march on Erzerum. V Corps began its march on 23 February. XVI Corps and the 5th Infantry Division left on 10 March. These reinforcements arrival in the Caucasus area had little effect on Russian holdings. Formed into the 2nd Army, the units were not ready to fight until late June. In that time Iudenich’s men consolidated there gains and were able to withstand the counter offensive.