George Lincoln Rockwell was the son of vaudeville comedians, served in the U.S. Navy in WWII and Korea, honeymooned at Berchtesgaden, founded the American Nazi Party, promoted White Power, baited blacks and Jews, ran for governor of Virginia, made it into a Bob Dylan lyric, was played on screen by Marlon Brando and was assassinated in front of his neighborhood laundromat while fetching a bottle of bleach.

On a Friday in August 1967, George Lincoln Rockwell, the charismatic and outspoken founder of the American Nazi Party (ANP), was slain, not by the government or some leftwing enemy, but by a member of his own organization.

The political ringleader who had achieved national notoriety was doing his own wash at a coin-operated laundromat in Arlington, Va., just across the Potomac River from Washington, D.C. A few minutes before noon on Friday, August 25, 1967, the American Nazi leader, whose presence had embarrassed the suburban community for nearly a decade, told the proprietor at the Econ-o-Wash that he had to return home for some bleach.

As the 49-year-old Rockwell slid into the seat of his fading blue-and-white 1958 Chevrolet, gunshots rang out from the roof of the Dominion Hills shopping center. Two bullets burst through the windshield. One struck Rockwell in the chest; the other missed, passing through the front seat. The car rolled into another vehicle as Rockwell crawled out of the right passenger door of the Chevy and fell out onto the parking lot, his box of soap powder and a copy of the New York Daily News sprawled near him. Bystanders called police, but in minutes the flamboyant—and ordinarily well guarded—leader of the modestly sized American Nazi movement had died of a shot through the heart.

Within half an hour, Arlington police would arrest not an anti-Nazi, but a fellow Nazi—29-year-old John Patler, a Greek-American and former Marine from New York City. Patler had risen to the No. 4 slot in the hierarchy of the party faithful, most of whom lived in a fortified “barracks,” a swastika-bedecked old house across the street from the shopping center.

Rockwell’s father (George “Doc” Rockwell), reacting to the news of the assassination, said his son had always known he would die in such a fashion. “I think he would have liked to get rid of the whole Nazi mess,” he told a reporter from his home in Maine. “He was more afraid of his own people than people were of him.”

The American Nazis’ slain, hypnotic commander was born in Bloomington, Ill., on March 9, 1918. He was the son of vaudeville comedians who counted among their friends Fred Allen, Fanny Brice, Jack Benny and Groucho Marx. Following his parents’ divorce, the young Rockwell attended prep school in Lewiston, Maine, before enrolling at Brown University in Providence, R.I., to study philosophy. He soon dropped out and served as a pilot in the Navy during World War II. He then attended the Pratt Institute of Art in Brooklyn, N.Y., where he developed the drawing talents he would use to create Nazi fliers.

After launching a short career in advertising, George Lincoln Rockwell married and fathered three children. When the Korean War broke out, he was called up and stationed in San Diego. He left his family when he was assigned to a U.S. naval air facility in Iceland. There, Rockwell read Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf and became obsessed with Aryanism and the worldwide threat of communism. In 1953, only months after his first marriage ended in divorce, he married an Icelandic woman and honeymooned in Germany at Hitler’s retreat town of Berchtesgaden. He sired four more children.

In the mid-1950s, in a move that would estrange him from his second wife and family, Rockwell returned to the United States and conceived the American Nazi Party. He moved to the suburbs of the nation’s capital in 1958 to begin his climb as a national newsmaker whose every public statement carried shock value. The literature his group printed on its own presses spoke of the “lie” that 6 million Jews were killed by Hitler, and Rockwell was heard to say, “Bring me 15 Jews and we’ll make Anne Frank soap.”

Rockwell’s violent rhetoric prompted a court-ordered psychiatric evaluation of him at St. Elizabeth’s Hospital in Washington in 1960, but he was found to be of sound mind. He later boasted that he had been arrested 100 times but never convicted by a jury. In 1966, when he appeared in New York City criminal court on charges of incitement to riot through anti-Semitic remarks, Rockwell wore a bulletproof vest. He’d been shot at before, and had unsuccessfully sought permission to carry a pistol.

From the beginning of his movement, Rockwell used a variety of publicity-generating tactics to spread his message of hate against Jews and blacks. American Nazis picketed Israeli Prime Minister David Ben-Gurion during his 1960 visit to Washington. That year, after New York City Mayor Robert Wagner banned Rockwell from speaking at a July 4 celebration in Union Square, the ANP picketed the White House. They demonstrated at theaters showing the 1961 movie Exodus, earning Rockwell a mention in a lyric by protest singer-songwriter Bob Dylan. The Nazis marched in front of nightclubs that booked black entertainer Sammy Davis Jr., whose wife was white, and who had previously converted to Judaism. Having established branches in several states in the early 1960s, the ANP was trailing and heckling the civil rights Freedom Fighters marching with Martin Luther King Jr. in the South. In 1965, the same year that Rockwell ran for governor of Virginia and garnered 6,366 votes, the California Justice Department investigated Rockwell’s West Coast followers for threatening violence. In Arlington, Rockwell’s grinning blond “stormtroopers,” wearing swastika armbands, picketed Jewish businesses and became familiar faces at school board meetings, where they protested newly enacted school integration. One flier read, “You can beat the federal race mixers.”

By 1966 his proclamations of “White Power!” made him notorious enough for African-American author Alex Haley to interview him for Playboy magazine. (In the late 1970s, when Haley’s family’s story was made into the TV series Roots, Rockwell was portrayed by Marlon Brando in the sequel.) Rockwell told Playboy that he foresaw serious race riots and that he planned to be president of the United States by 1972. He made an unsuccessful attempt to cozy up to conservative theorist William F. Buckley Jr. His Nazi associates presented their leader to Christian fundamentalists as a modern “Saint Paul.”

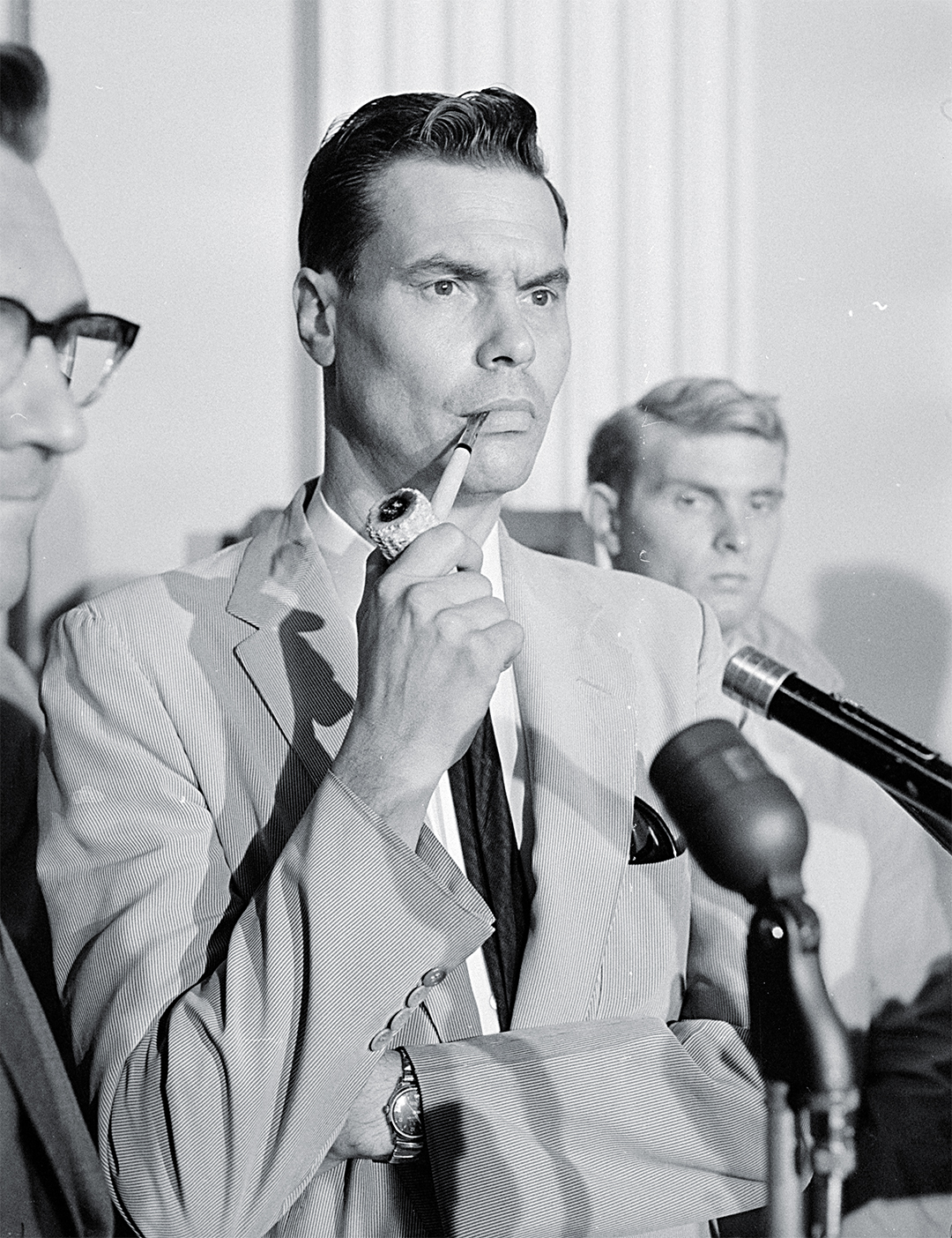

With his flashing eyes and 6-foot-4 frame, “Rockwell has all kinds of leadership ability,” said a 19-year-old College of William and Mary student who tape-recorded an interview with Rockwell at his headquarters in July 1967. “He never hesitates when he speaks, and he almost glows with confidence. It’s easy to see how he can use his power on ignorant people.” Ruby Pierce, an employee of the Arlington laundromat who was perhaps the last to talk with Rockwell, said: “He was polite and charming. He was tall and handsome and looked like a businessman.”

Some who grew up in Arlington in the late 1950s and 1960s have memories of passing by the various homes the American Nazis used as headquarters, most visibly the one that bore a large wooden sign reading: “White Man…Fight! Smash the Black Revolution Now.” As youngsters, they sometimes got their thrills by phoning to hear the tape-recorded hate messages delivered by Rockwell associate and white supremacist William Pierce, who would go on to write The Turner Diaries, a novel that in the early 1990s inspired Oklahoma City bomber Timothy McVeigh.

During the ANP’s presence in Arlington, there developed a division among residents and onlookers as to whether the odious group should be scrutinized—or simply ignored. “Most Arlingtonians disregarded them,” recalled longtime Arlington resident Jean Mostrom, who heard the sirens on the day of Rockwell’s shooting. Working as a census taker in 1960, Mostrom was instructed not to risk knocking on the door of the house set far back in the woods, which some had nicknamed “Hatemonger Hill.”

U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy declined to put the American Nazi Party on a list of dangerous domestic groups because he did not want to boost its notoriety. Similarly, newspapers in Germany, where memories of Nazis were still fresh in 1967, gave Rockwell’s assassination only brief coverage. Peak membership in the party probably never reached more than 50 to 60, according to John Rees, a Baltimore-based author of a newsletter on fringe groups. A few other reliable sources place the total hardcore membership at less than 200, although there may have been a few thousand unofficial supporters who helped from time to time.

Reporters assumed that many of the Nazi “stormtroopers” were actually FBI infiltrators, recalled then Washington Star reporter Ken Ikenberry, and one putative member of the ANP in 1960 was actually Washington Daily News reporter George Clifford, working undercover. Some reporters were reluctant to venture onto the Nazi property for fear of the reputedly vicious German shepherds (one of which was named J. Edgar, after FBI Director Hoover) in the yard. Yet Ikenberry said that when he and CBS News reporter Daniel Schorr raced to the barracks on the afternoon of the shooting, the dogs seemed timid.

The journalist who took the Nazis most seriously was Herman J. Obermayer, editor and publisher of the daily Northern Virginia Sun. In an oral history conducted by the Arlington County Library staff in 1987, Obermayer, who is Jewish, said: “The American Nazi Party in Arlington, I felt, was a terrible blur on the community, and that their activities should be fully reported. I always thought [the Nazis] stayed here because they were welcomed here. I really believe that if you [had] made them miserable enough, they would have left.” The three other daily newspapers, The Washington Post, the Washington Star and the Daily News, all followed a policy of “quarantine” that attempted to keep the Nazi publicity hounds out of the limelight.

As he declared in Sun editorials and in an article in the Columbia Journalism Review, Obermayer wanted authorities to investigate more aggressively whether the Nazis paid their business taxes and maintained licenses for their printing operations. And he spoke of a baby girl he heard had died while living in the Nazi barracks, which the commonwealth’s attorney never investigated.

One group of Arlingtonians who decided to take on the ANP was an organization called Citizens Concerned. In 1961 some 50 local civic activists began meeting to share information on the Nazis compiled by the Anti-Defamation League and the Jewish Community Council of Greater Washington. They were worried about Nazi indoctrination of local high school students.

Citizens Concerned eventually approached the commonwealth’s attorney with requests for public education campaigns and an investigation into possible Nazi violations of zoning ordinances. After studying the party’s articles of incorporation, the group approached the Virginia State Corporation Commission and successfully lobbied it to revoke the party’s charter. In 1962 the Virginia General Assembly declared Rockwell’s group an enemy of the state.

The financing of Rockwell’s band of underemployed and marginalized agitators has always been murky. But funding quite likely was one reason he chose Arlington as headquarters for a party that would eventually form chapters in Los Angeles, Chicago, San Francisco, Philadelphia and Dallas, as well as establish links to counterparts overseas. According to historian Frederick J. Simonelli in his 1999 American Fuehrer: George Lincoln Rockwell and the American Nazi Party, the struggling Rockwell depended on his mother for income all his life. Once famous, he made money from campus speaking fees. And he had some wealthy benefactors among far-right Christian groups in California and Dallas, although the Dallas connection may have been exaggerated. It also was rumored that he received money from Arab governments angered by the creation of Israel.

Yet another source of direct support was a Baltimore heir and white supremacist named Harold Noel Arrowsmith Jr., who owned a house in Arlington and lent it to the Nazis in the late 1950s. Given its unpopularity in the community, the party periodically and secretly shifted the locations of its headquarters and dormitory, each of which would play host to numerous public skirmishes.

During one confrontation, on the evening of April 21, 1959, Arlington police and the commonwealth’s attorney William Hassan, armed with a search warrant, raided a Rockwell home, finding a pistol, a revolver, rifles and 10,000 anti-Jewish pamphlets. Some 100 neighbors looked on as Nazis marched in and out of the home giving the “Sieg Heil ” salute. Police charged various Nazis with disorderly conduct and maintaining a public nuisance.

In December 1965, the Internal Revenue Service locked the party out of another headquarters for nonpayment of taxes of $7,000. After the IRS confiscated their printing equipment, the Nazis moved their printing operations to a plant outside Fredericksburg, Va.

In 1968, when the post-Rockwell Nazis used subterfuge to move into what would be their final Arlington headquarters, a local dentist and county board member who was suddenly forced to share a building with them told a reporter he found the prospect “nauseating.”

Observers who glimpsed the inner sanctum of Rockwell’s headquarters were impressed most by the utter banality. New York City police investigator Tony Ulasewicz, later famous during the Watergate scandal, visited Rockwell in late 1961 and recalled in his 1990 memoirs titled The President’s Private Eye:

What greeted me was a grubby haunted house….Clearly, this was no showpiece that would attract membership into Rockwell’s party. His glowing, published accounts of his party’s progress had been nothing more than a pack of lies. As I looked around, I noticed that bullet holes punctured all the walls of the house…I also saw a pack of unpaid bills high on a table. Rockwell’s electricity had been turned off, and he used kerosene lamps to light the place.

Disgust at Rockwell’s domestic habits was expressed even by one of his own. In a typescript memoir acquired by Arlington Public Library, a former housemate noted wryly that “Link,” as Rockwell was called, “as usual” took the largest bedroom. “Link would usually sit around and read or sleep away most of the day while the rest of us would work or look for work,” he wrote. “Many sympathizers would bring food over to the headquarters during the winter months, and Link would take the choicest food and hog it up and leave the scraps for everyone else.”

Following the assassination, the defiant and—to many observers—ludicrous behavior of the American Nazi Party was on full display during the controversial effort to bury the slain leader on August 30, 1967. Because he was a military veteran, Rockwell had won a Pentagon ruling that entitled him to be interred in a national cemetery. But military officials refused to allow his followers to use Nazi rituals, uniforms and flags in the ceremony. Although that refusal was challenged on free-speech grounds by the American Civil Liberties Union, the courts upheld the Pentagon’s order.

At the National Cemetery in Culpeper, Va., therefore, Nazis and Defense Department military police faced off in a six-hour “classic comic fiasco,” as reporter Ikenberry recalled it. In the end, instead of being buried, Rockwell’s body was returned in a hearse to an Arlington funeral home to be cremated. His ashes were last seen with his 33-year-old successor, Matthias Koehl Jr. The Nazis then held a memorial service at their Wilson Boulevard barracks, which drew some 30 admirers from as far away as Pennsylvania, Illinois and Wisconsin.

As the funeral fiasco played out, Rockwell’s suspected assassin was sitting in the Arlington County jail. His subsequent trial and conviction for the murder of the charismatic Rockwell would crimp, but not derail, the unlikely American Nazi movement.

John Patler had been arrested at a bus stop in a residential neighborhood a mile from the scene of the crime. Suspiciously running while wiping his head with a towel, and with his pants wet to the knees, Patler had been spotted by a deputy police chief who knew the regular Nazis by sight.

What was believed to be Patler’s discarded raincoat and baseball cap were found in a yard behind the shopping center, and his suspected weapon, a 40-year-old German Mauser semiautomatic pistol that fired 7.63mm rounds, was recovered by a patrolman from a stream in a park along his escape route.

In the run-up to the December trial, it emerged that Patler, who had been photographed standing with Rockwell at Nazi rallies, had maintained on-again, off-again membership in the party. A “swarthy, greasy Greek,” as one Nazi labeled him, Patler was suspected of being a Marxist, and he had also pressed to rid the American party of its German trappings. It was Patler’s idea to change the name from the American Nazi Party to the National Socialist White People’s Party, a switch that took place in January 1967.

After joining the party during its formative years, Patler had left in 1961 to set up a rival group, then returned a couple of years later. He had split again in April 1967, but a photostatted letter from Patler found in Rockwell’s wallet after the killing suggests that he again was seeking to reconcile with his mentor.

Soon after the arrest, one of Patler’s attorneys, Helen Lane, a controversial former member of the Arlington School Board and longtime Rockwell friend, announced that her client would plead not guilty. The commonwealth’s attorney sought the death penalty.

At the trial, defense attorneys argued that Patler was not among the four persons who reportedly were aware that Rockwell had left the barracks to do his laundry on that August day. Instead of being at the shopping center, the defense said, Patler—who did not drive—was three miles away at his home until 11:45 a.m. He had run errands with his wife and child, Patler claimed, and after he and his wife had quarreled he had gone out for a walk.

The prosecution reported having found footprints traced to Patler on the roof of the shopping center. Employees of nearby shops said they tried to chase the killer. A witness testified that he saw a man fitting Patler’s description running through the residential neighborhood a few minutes after the gunshots, and realized he was right a couple of days later when he saw Patler’s picture in the newspaper. Prosecutors also set out to prove that the murder weapon had been test-fired on Patler’s father-in-law’s property in Highland County, Va.

After a four-hour deliberation on December 15, 1967, a jury of 10 men and two women found Patler guilty of murdering Rockwell. Patler’s wife Alice screamed, “No, no, no!” He was given a 20-year prison sentence.

While still free awaiting an appeal of his murder conviction in 1969, Patler won a $15,000 libel suit against a Nazi official who had told the FBI that Patler had stolen the gun used to kill Rockwell. After losing an appeal to the Virginia Supreme Court in the murder case, Patler served four years at a prison near Martinsville, Va. He was paroled in August 1975, but parole violations would land him back in prison until the early ’80s. In 1977 he had announced he would change his name back to its Greek original, John Christ Patsolos. After his release, he reportedly went on to launch a Spanish-language newspaper, but after it failed, he became a commercial artist.

In his estate, Rockwell left behind $257 in cash, his trademark corncob pipe and various writings. His successor as leader of the party, Koehl, was even accused by some party members of masterminding Rockwell’s assassination. Koehl tried to further the movement but he was no match for Rockwell as a rabble-rousing speaker.

Newspapers in subsequent years would report sporadic feuds and even gun battles against and between Nazis. In 1976, during Arlington’s Bicentennial Independence Day parade, the Nazis marched with a swastika-decorated drum corps, and in 1977 some 30 to 40 antiracist protestors threw rocks and eggs at Nazi headquarters. On the 10th anniversary of Rockwell’s shooting, Koehl led a commemorative ceremony at the spot where Rockwell died, laying a wreath and painting a swastika on the pavement.

In 1982 an Arlington Nazi named Martin Kerr announced that the organization was changing its name to New Order and moving to the Midwest, later settling in New Berlin, Wis. Another Arlington-based Nazi, Harold Covington, moved back to his home in North Carolina and set up a Nazi training camp near Raleigh. He later ran unsuccessfully for state attorney general.

Into the 21st century, Rockwell’s legacy was being carried on by the National Socialist White Peoples’ Party headed by Covington, using the name Winston Smith. The group promotes and sells Rockwell’s writings and audiotaped speeches on Web sites. But when today’s Arlingtonians tell the story of their hometown, the name George Lincoln Rockwell is seldom mentioned.

Originally published in the February 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.