Men who lost their dominant right hand entered penmanship contests to show they could still be productive

A UNION VETERAN of several major battles, including Antietam and Gettysburg, artillerist George Bucknam was wounded during the Wilderness fighting of May 5-7, 1864. “Through the carelessness of one of our own men,” he explained later, “my gun prematured, as I was driving out my sponge staff after ramming a 12-lb. shot in the gun, and blowed my right hand off above the wrist, and three fingers of my left hand.” In a narrative submitted to a left-handed penmanship contest in 1867, Bucknam detailed the effects of the explosion: “[It] burst the drum of my left ear, and burnt my face, and knocked me down, and jarred me considerable, but left me sensible, so I got up and walked off the field.”

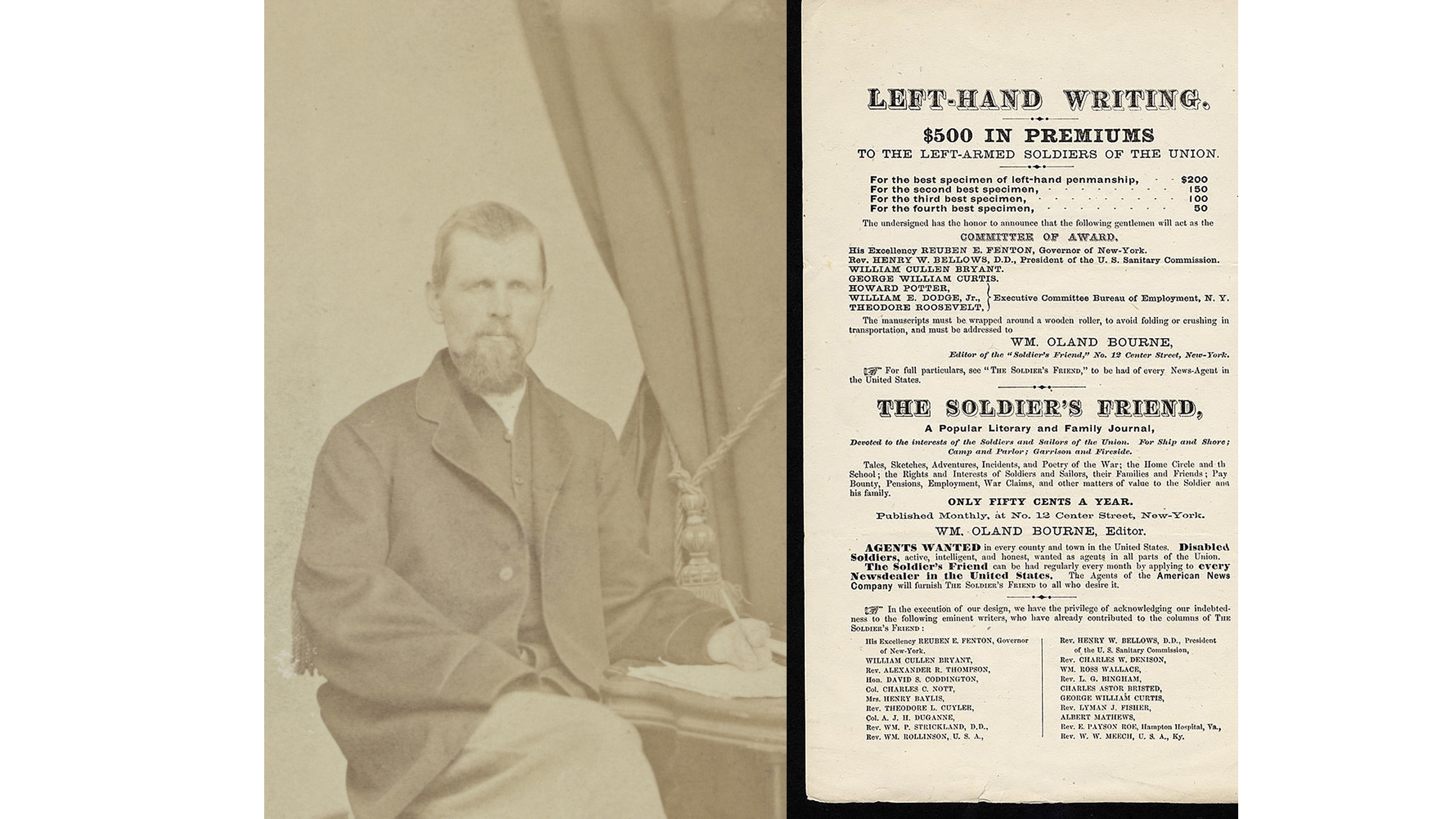

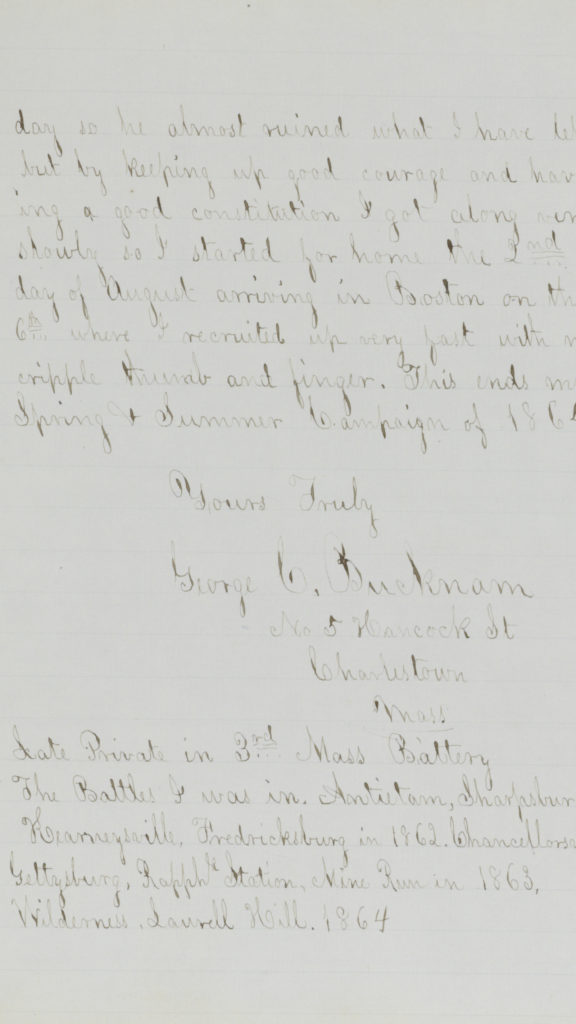

Writing with his left hand, Bucknam methodically described the process of his wounding and did not shy away from revealing graphic elements of his suffering under “the splendid accomadations [sic] that [the] army afforded.” When Bucknam reached the rear, “the Doctors began their butchering the same as they were used to and [I] was soon a man with a few hands and less fingers than [I] had 2 hours before.” Upon reaching Washington, D.C., Bucknam’s wounds—which had not been dressed for four days—“were so full of vermin…they very near frightened some of the Milk and Water Doctors.” On Bucknam’s insistence, the doctors went to work: “[I]t took three docs three hours, to get the vermin all off.” Another doctor’s knife was “so handy that he kept cutting a little every day.” Addressing the contest judges, Bucknam wrote, “Perhaps you can imagine my feelings for the first twenty-four hours after I was wounded thinking I should have to part with the remaining thumb and finger.” A photograph

Bucknam submitted along with his narrative showed he kept his remaining thumb and finger, using them to write about his experiences and share his suffering.

Hundreds of left-armed veterans like Bucknam participated in two left-handed penmanship contests between 1865 and 1867, organized by William Oland Bourne, a hospital volunteer, abolitionist, newspaper editor, and poet. The contests called on men who lost their right arms while fighting for the Union to submit “specimens” of their best left-handed “business” writing in the form of personal statements. Bourne wanted to help veterans reenter the work force and to become economically viable citizens. They might not be able to push a plow, but they could definitely push a pen. Entrants vied for cash premiums. For the first contest, $1,000 was divided into prizes ranging from $20 to $200. A second competition in 1867 offered ten $50 prizes. Directions asked entrants to submit signed affidavits affirming their disability and encouraged photographs.

The ten prizewinners of the second competition, out of 113 submissions, also received letters autographed by celebrated officers such as Grant, Farragut, and Sheridan.

Consciously participating in a collective act of testifying to national trauma, the contestants announced their membership in a unique group of veterans. They also presented their reconfigured bodies and lives to the public. Bourne’s contests argued that ostensibly disabled men could replace their right arms with their left arms. However, the contestants and their entries present visible evidence (in the form of surprisingly elegant or understandably sloppy left-handwriting specimens) of the difficulties of adaptation and recovery.

Like Bucknam, Alfred D. Whitehouse submitted a photograph of himself and provided the graphic details of his wounding. A member of the 8th New York Militia, he was wounded in the first major battle of the war, Bull Run. He submitted specimens to both contests and won a prize for ornamental penmanship. His first entry consisted of a prose account of his military experience and his second revealed that his penmanship skills far exceeded his poetical ones.

In describing his wounding and eventual capture by Confederates, Whitehouse wrote:

“I was wounded about 3 P.M. in the right arm by a rifle ball near the shoulder and after remaining upon the battlefield about six days among my wounded, and dyeing [sic], comrades, till my shattered arm was full of maggots, then I was put, with many others, on board of dirty Cattle Cars, without even straw to cover the manure.”

On the journey from Manassas to Richmond, “from three to five died in each car…as prisoners[;] sutch [sic] was rebel humanity.”

Though his poetic efforts are less than impressive, they indicate one of the ways in which left-armed veterans framed their bodily cost. Whitehouse proudly aligned his sacrifice with the redemption and salvation of the Union. “The right arm’s gone,” he declared, “the Nation yet remanes,/Tho many perished yet we are saved,/The right will triumph over wrong/Tho it leave us but one left arm strong.” Like a number of contestants, Whitehouse puns on the words “left” and “right,” invoking and refuting the stigmas associated with left-handedness. Many contestants mourned the loss of their right arms and detailed the difficulties of adapting to life as left-armed men. But they also presented their newly abled left arms as proof of resilience and recovery.

Bourne’s left-handed penmanship contests provide invaluable insight into how Civil War soldiers narrated and commemorated their experiences. George Bucknam, Alfred Whitehouse, and other members of the Left-Armed Corps insisted on the importance of their stories and their bodies to the literary record of the conflict. In putting pen to paper, they produced lasting testaments to loss and perseverance, suffering, and survival.

This post first appeared on the blog of the National Museum of Civil War Medicine (civilwarmed.org) on February 21, 2019. Allison M. Johnson is assistant professor of English at San Jose State University. Her book The Scars We Carve: Bodies and Wounds in Civil War Print Culture, was published by LSU Press in April 2019. She is working on an edited collection of the Left-Armed Corps’ writings.