Shopkeepers, miners and housewives in Wallace, Idaho, had been complaining about the smoke for most of the summer of 1910. It had rained little since spring, and the tinder-dry forest on the surrounding slopes had spawned numerous small blazes. The smoke, at times verging on a fog, enveloped town. The fledgling U.S. Forest Service was struggling to keep up with the fires. In mid-August ranger Ed Pulaski, one of the service’s few experienced men, ventured out with a crew to fight fires near the west fork of Placer Creek, about 5 miles south of town, while fellow ranger Henry Kottkey and his men battled a blaze on Loop Creek.

“The fire’s blowing up,” Kottkey soon reported to supervisors. “I’m worried.”

He was also concerned about wife Bertha, who had entered Providence Hospital in Wallace to give birth to the couple’s third child. Others were growing anxious, too. In Taft, Mont., which the Chicago Tribune had recently labeled “the wickedest city in America,” and in other rough settlements in the northern Rocky Mountains—Saltese in Montana, and Mullan, Avery and Grand Forks in Idaho—saloonkeepers, railroad workers and prostitutes kept an eye on the burning hills.

On Little Beaver Creek, north of Thompson Falls, Mont., 3-year-old Lily Cunningham had watched in fascination as glowing plumes of orange smoke drifted across the night sky. She could tell her mother was frightened, as she’d been crying. But Lily found the orange clouds beautiful.

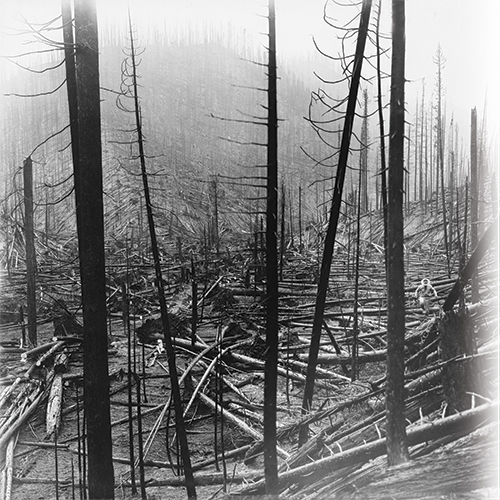

‘The country has been wiped clean,’ one survivor recalled of the stark landscape left in the fire’s wake

Other residents of the northern Rockies, especially those with memories of earlier fires, began plotting their escape and planning what they might take with them on horseback, in wagons or on the train. Some buried sewing machines, tools and trunks filled with personal possessions and family keepsakes for later retrieval.

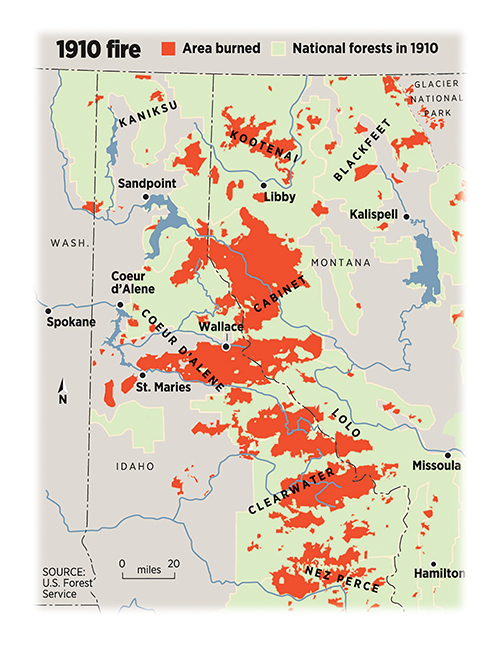

Within days winds swept down from the low hills of the Palouse region of southeastern Washington, fanning the flames and merging the thousands of small fires into a single massive blaze. Dubbed the “Big Burn” or “Big Blowup,” the resulting firestorm remains the largest wildfire known to have hit the United States and, as one historian wrote, “possibly the biggest ever in North American history.” It scorched some 3 million acres of virgin forest, mainly in northern Idaho and western Montana, and killed dozens of people, mostly firefighters.

“The country has been wiped clean,” one survivor recalled of the stark landscape left in the fire’s wake.

The first report of fire in the northern Rockies that season had come in on April 29, earlier than usual, from the newly declared Blackfeet National Forest of northwestern Montana. As spring yielded to an unusually dry, hot summer, reports flooded in of hundreds of small blazes, many sparked by lightning, others by cinders thrown off by steam locomotives or through the careless actions of miners and even inexperienced forest rangers. A strong lightning storm over the Bitterroots on the night of July 26 exacerbated the situation by igniting a flurry of fires that stretched the Forest Service lines and began to get out of hand.

“For every fire we put out,” one service member told a Missoula, Mont., newspaper, “a new one is reported.”

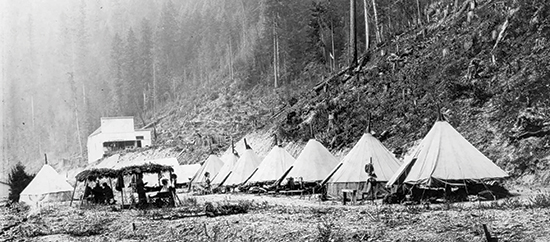

By early August an estimated 3,000 fires were burning across Idaho, Montana and Washington, including the Bean Creek fire, the Lakeview and Loop Creek fires, the Mineral County fires, the Placer Creek fire, the Trout Creek fire and countless others with no name. The Forest Service was battling them earnestly but was short of supplies and staff. Pressed for manpower, it had resorted to recruiting immigrants fresh off the train and prisoners from area jails.

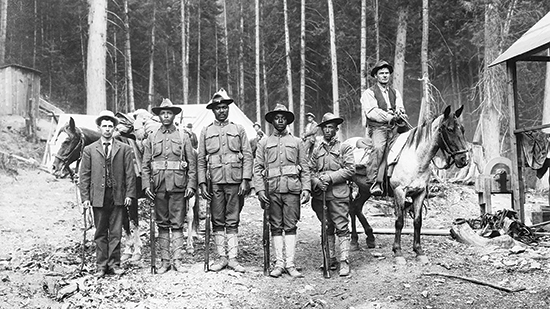

In desperation the Forest Service appealed for federal aid to President William Howard Taft, who on August 7 authorized the dispatch of Army troops to help with firefighting efforts. Twenty-five hundred soldiers eventually joined the fire lines. Most were buffalo soldiers of the 25th U.S. Infantry from Fort George Wright, north of Spokane. Unfortunately, like the newly recruited immigrants, the corralled jail inmates and the Forest Service neophytes, these black soldiers had little or no experience fighting forest fires.

Regardless, they did what they could, even trying to induce rain. Beginning in mid-August, on direction from their officers, the buffalo soldiers spent 60 straight hours firing cannons and dynamite charges into the sky. Their efforts were prompted by the timeworn observation that rain often followed major military battles involving cannon fire.

This time the tactic failed—no rain came.

In Wallace and Taft, Saltese and Avery, concerns mounted.

The region’s longtime miners and shopkeepers were no strangers to fire. Wallace, founded in 1884 when namesake Colonel William R. Wallace built a cabin on the promising townsite, had grown as fortune seekers came after gold and silver ore in the surrounding hills. By 1890 it was thriving. That July, however, a residential fire fueled by strong winds devastated the business district, destroying 19 saloons and hotels, three livery stables, a bank, a theater, the newspaper office, doctors’ and lawyers’ offices, stores and shops.

Now wildfire threatened.

Burning embers had drifted down into town and set afire a couple of canvas awnings. Though alert townspeople had quickly put out those blazes, on August 19 local insurance companies, noting with alarm the rapidly encroaching flames, stopped issuing fire insurance policies.

As the glowing orange clouds that had so fascinated 3-year-old Lily Cunningham approached the family home on Little Beaver Creek, her parents released livestock, secured belongings from the cabin, piled whatever fit into their root cellar and fled to a neighbor’s house. Put to bed with the neighbor’s small children, Lily watched through the window as the adults and older children carved out a fire line and doused any embers landing in the farmyard.

On August 20 the winds came. “[That] Saturday afternoon,” historian Tim Egan wrote in his 2009 book The Big Burn, “atmospheric conditions gave birth to a Palouser that lifted the red dirt of the hills and slammed into the forests—not as a gust or an episodic blow, but as a battering ram of forced air.”

When the wind hit the downslopes, it accelerated, flattening out the flames and incinerating everything in its path. Hydrocarbons in the resinous sap of the predominant Western white pines boiled out of the trees, releasing highly flammable gas that spread across hundreds of square miles and detonated spontaneously as it heated.

“In a matter of hours,” the Forest Service noted, “fires became firestorms, and trees by the millions became exploding candles. Millions more trees—sucked from the ground, roots and all—became flying blowtorches. It was dark by 4 in the afternoon, save for wind-powered fireballs that rolled from ridgetop to ridgetop at 70 miles an hour. They leaped canyons a half-mile wide in one fluid motion. Entire mountainsides ignited in an instant.”

By noon on August 21 roiling clouds of smoke had blacked out the sky as far south as Denver and as far north as the town of Saskatoon in Saskatchewan, Canada. People claimed to have seen night-flying bats at midday. Smoke from the fire, the Forest Service reported, “turned the sun an eerie copper color in Boston. Soot fell on the ice in Greenland.” As the fire grew, people in upstate New York, some 2,000 miles east of Wallace, could smell smoke on the wind, and ships in the Pacific Ocean to the west had trouble navigating by the stars due to the smoke obscuring the night sky.

The windblown firestorm persisted a full 48 hours. “For pure physical force,” Egan says, “we haven’t seen anything like it since.” Ranger Edward G. Stahl recalled flames hundreds of feet high, “swooping to earth in great darting curves, truly a veritable red demon from hell.”

Ranger Edward G. Stahl recalled flames hundreds of feet high, ‘swooping to earth in great darting curves, truly a veritable red demon from hell’

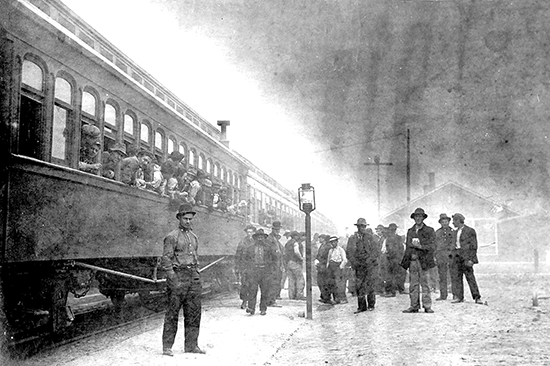

In Wallace fear reached a fever pitch. Authorities ordered trains to evacuate the town’s women and children. On August 19 Bertha Kottkey had given birth to a son, naming him after his father. As the fires threatened town, Bertha and Henry Jr. joined other patients and staff from Providence Hospital evacuating by eastbound train. They just made it. Immediately after the caboose crossed a trestle on the outskirts of town, the charred structure collapsed. Arriving safely in St. Regis. Mont., the patients and staff transferred to a train bound for Montana’s capital, Helena, where they caught still another to Missoula. They had no way of knowing it at the time, but Providence Hospital would be one of the few buildings in the fire-stricken east end of Wallace to survive.

Meanwhile, back in town men had been ordered to the fire lines, and authorities had released prisoners from the city jail to help. (Only two, an accused murderer and a bank robber, were kept in handcuffs.) Ashes fell like snow. That evening a large ember came down amid buckets of press grease and solvent-soaked rags beside the Wallace Times building. The resulting blaze ignited the newspaper office, then spread quickly to an adjoining mill, a boardinghouse, two hotels and the railroad depot.

As the fire spread, an elderly man named John Boyd, whose son happened to be a Wallace fire captain, finally headed for the depot to board one of the waiting trains. Suddenly remembering his beloved pet parrot, he turned back toward home to retrieve the bird. Searchers later found their bodies side by side in the street. Master and bird had died of smoke inhalation.

Beyond the city limits a vast swath of the northern Rockies was ablaze.

One Mullan resident likened it to being “inside a deep bowl which is completely lined with seething flames.” Railroad bridges burned and collapsed. Wherever possible, trains took refuge in tunnels. Grand Forks, a canvas-and-wood town on the Idaho-Washington border, simply disappeared when the firestorm swept through. “The whole horizon to the west was aflame,” one ranger reported.

Amid the blazing hills the understaffed Forest Service did what it could with its ragtag force of rangers, hasty recruits and buffalo soldiers. As the fires spun out of control, Henry Kottkey and crew abandoned the line on Loop Creek and hurriedly sought shelter in the cooler air of a large railroad culvert. To the east ranger Ed Pulaski led his 45-man crew and its two horses into a mineshaft. There the men shrouded the tunnel entrance with blankets, soaked them with standing water from the shaft and finally dropped to the floor where the air was breathable.

The buffalo soldiers kept fighting. In Wallace and other places they worked through the night hauling water buckets and setting backfires. “Not a man in the lot knew what a yellow streak was,” one Avery resident recalled. “They never complained. They were never afraid.”

Pulaski and crew finally emerged after five hours face down in the mud of the mineshaft, the fire having burned past them. But five men and the two horses lay dead, and the others were in varying states of distress. Pulaski himself was in dire shape. Burned on his hands, head and face, he was blind in one eye and afraid he might lose the other. Though the soles of their shoes were burned through, the crew headed down the smoldering mountainside. Leading the way, Pulaski tried his best to follow a familiar path now obscured amid the charred remnants of the forest. The ragged group finally stumbled across a group of women searching the burned-out woods on Placer Creek for survivors. The rescuers greeted the men with coffee and whiskey.

They had made it. Kottkey and crew had also survived, and the exhausted buffalo soldiers soon returned to their post north of Spokane.

By the evening of August 21 the winds that had fueled the firestorm had moved east, and storm clouds began rolling in from Washington. Then it rained, a steady drenching rain, a gully washer that smothered the fires, leaving a moonscape of damp ash and ghostly snags.

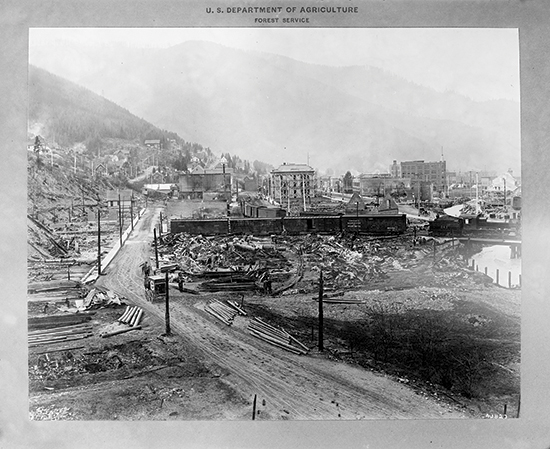

At its height the Big Burn had covered an area the size of Connecticut. It razed more than 3 million acres of virgin forest through Idaho, Montana, Washington, Oregon and British Columbia, including 2.6 million acres of national forest and 521,184 acres of private land. Timber losses approached a billion dollars. The fire killed at least 87 people, 78 of whom were firefighters. (Fifty-four of the latter are interred at the St. Maries 1910 Fire Memorial, marked by a 6-foot granite slab at the cemetery in that Idaho town.) An exact count of civilian casualties could not be established due to scanty records kept at the time. Furthermore, those fleeing the fire had scattered throughout the wilderness. Some were entirely consumed by the flames, including those in the vanished settlements of Grand Forks and Taft. A third of Wallace, the entire east end of town, lay in ashes. A magazine described the region as a “graveyard, random clumps of fried and half-burned trunks, a forest no more.”

With the passing of the welcome rains the roads opened, the trains began running again and evacuees trickled back in to dig up their buried sewing machines and family keepsakes.

After a lengthy recovery Pulaski returned to work for the Forest Service. In 1931, just shy of his 65th birthday, he died from complications of his injuries at home in Coeur d’Alene, Idaho. While Kottkey and his men had emerged unscathed from the culvert in which they’d sheltered, Henry and Bertha’s home in Falcon, south of Wallace, had been destroyed. The couple and their three children moved to Florida. Eventually, as the bad memories faded, they moved back and raised five more children. Son Henry Jr. later joined the Forest Service.

Three-year-old Lily Cunningham and family had survived their ordeal, as had all but one of the family cows her parents had released before the fire. Their only remaining belongings were the clothes on their back and a cherished rocking chair, family photos and other items they’d stored in the root cellar. Yet the family stayed in the region and rebuilt. Lily lived long enough to be recognized as the last known survivor of the Big Burn.

In the aftermath of the fire the Forest Service gained in stature and received the increased funding and manpower it needed to implement a new fire suppression policy, one that held every blaze was to be extinguished wherever and whenever it occurred at whatever cost. In the decades that followed the hard-line policy seemingly bore fruit, as rangers were quick to spot, attack and extinguish most wildfires. There were no more Big Burns, no more destroyed towns.

But the policy had an unintended consequence. “Over time,” Idaho forest ecologist Ryan Haugo explains, “the exclusion of fire from forested landscapes resulted in accumulating and dried-out fuels; denser, less diverse forests; and a recipe for catastrophic blazes once more. Add in a changing climate—with longer, hotter, drier summers—and it’s clear that the ‘fight at all costs’ approach to wildfire couldn’t be sustained.”

It had in fact left tracts of forestland vulnerable to bigger and more damaging fires, a fact forest ecologists didn’t recognize until the 1970s and the Forest Service itself didn’t fully accept until the 1990s. Ultimately backing away from the decades-old fire suppression strategy spawned by the Big Burn, Forest Service Chief Jack Ward Thomas declared its rangers would battle certain fires, while allowing others to burn.

“Fire is neither good nor bad,” Thomas said. “It just is.” WW

Wild West contributor and onetime newspaperman Chuck Lyons is a freelance writer based in Rochester, N.Y. For further reading he suggests The Big Burn: Teddy Roosevelt and the Fire That Saved America, by Timothy Egan; The Big Burn: The Northwest’s Great Forest Fire of 1910, by Don Miller and Stan Cohen; and Year of the Fires, by Stephen J. Pyne.