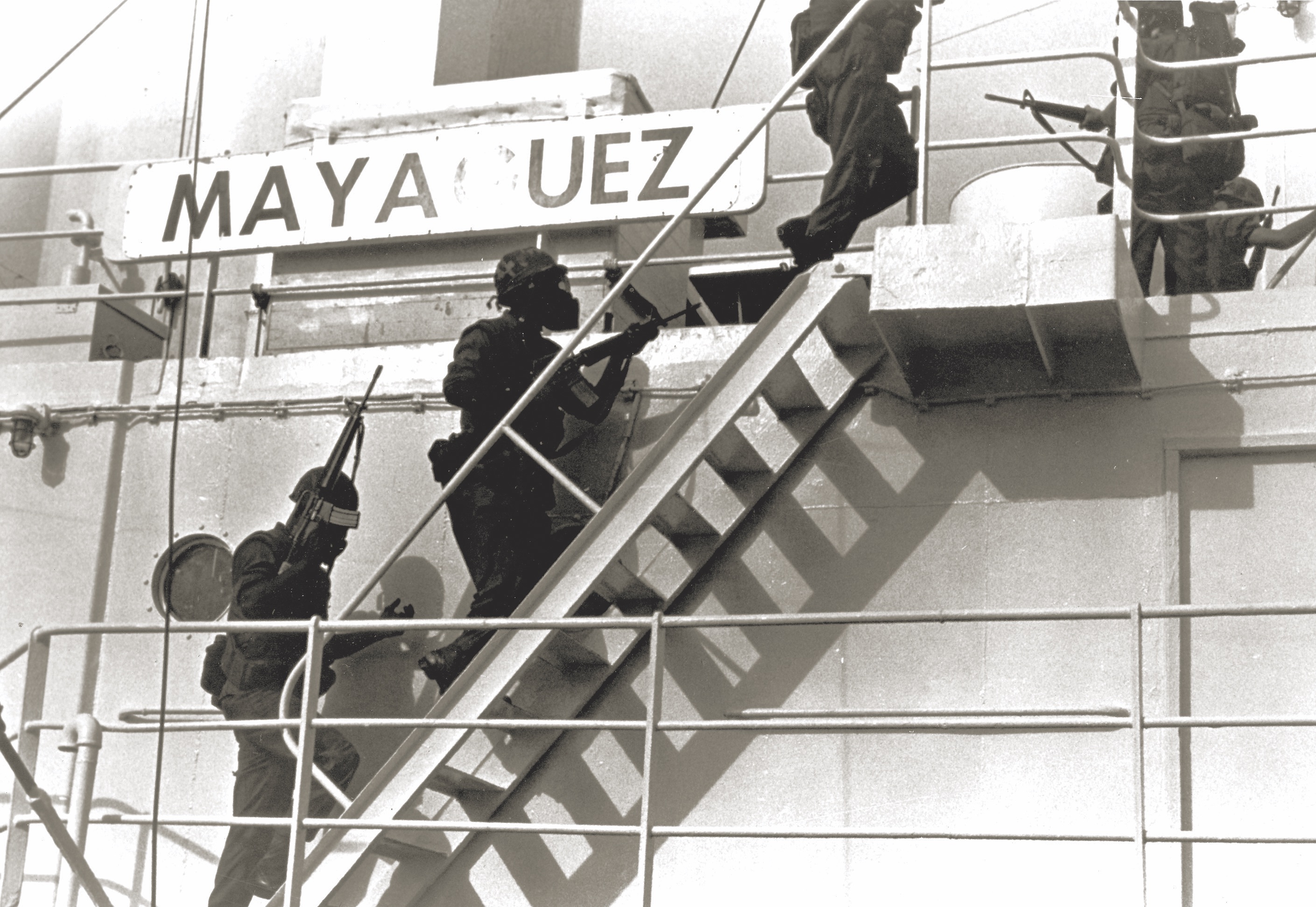

The humiliating April 29, 1975, image of U.S. helicopters evacuating Americans and Vietnamese from Saigon rooftops as North Vietnamese troops overran South Vietnam to win the Vietnam War was a political-military disaster damaging America’s global prestige. Two weeks later, the U.S. endured another humiliation in Southeast Asia. On May 12, the genocidal communist Khmer Rouge, who had conquered Cambodia on April 17 (and renamed it “Kampuchea”) seized the SS Mayaguez, an American container ship. They had attacked in small “swift boats” and were armed only with AK-47 rifles and rocket-propelled grenades.

The humiliating April 29, 1975, image of U.S. helicopters evacuating Americans and Vietnamese from Saigon rooftops as North Vietnamese troops overran South Vietnam to win the Vietnam War was a political-military disaster damaging America’s global prestige. Two weeks later, the U.S. endured another humiliation in Southeast Asia. On May 12, the genocidal communist Khmer Rouge, who had conquered Cambodia on April 17 (and renamed it “Kampuchea”) seized the SS Mayaguez, an American container ship. They had attacked in small “swift boats” and were armed only with AK-47 rifles and rocket-propelled grenades.

The attackers captured Mayaguez Capt. Charles T. Miller and 38 crewmen. Over the next three days, President Gerald R. Ford and his senior advisers wrestled with America’s response. U.S. forces ultimately recaptured the Mayaguez, and concurrently Cambodian officials released all the crewmen unharmed. However, during that operation the U.S. military lost 41 lives, including 23 Air Force support personnel accidentally killed in a helicopter crash—a total loss larger than the number of Mayaguez personnel “rescued.”

Christopher J. Lamb’s superbly researched book, The Mayaguez Crisis: Mission Command and Civil-Military Relations, is the definitive account of what happened, how it happened and played out, and what lessons should have been learned.

The Mayaguez incident is billed, Lamb notes, as “the last battle of the Vietnam War.” Actually, the incident is only peripherally connected to the Vietnam War, and linking the Mayaguez’s seizure to the war is a stretch, considering that all U.S. combat units had withdrawn by 1973.

The connections are merely coincidental: Chronologically, the Mayaguez capture was two weeks after Saigon’s fall; geographically, it was in Southeast Asian waters; and politically, regional disruptions facilitated the Khmer Rouge’s Cambodian conquest. But the Mayaguez incident was no more related to the Vietnam War than was North Korea’s 1968 capture of U.S. spy ship Pueblo.

The Mayaguez seizure more precisely represents the “first battle” of today’s ongoing “war on terrorism” promulgated by rogue states and nonstate terrorist groups—indeed, Mayaguez’s capture foreshadowed the tactics of today’s Indian Ocean pirates.

Revealingly, Lamb explains the true significance of the Mayaguez incident in relation to today’s global conflicts:

[A]n example of the courage and fortitude of American servicemen…an enduring symbol of what can go wrong in the planning and execution of military operations…[Importantly, U.S.] national security leaders have to decide between prioritizing the welfare of a small group of citizens or the broader national interests as a whole. This difficult choice arises not only when hostages are seized by foreign powers, but tacitly every time diplomats, intelligence personnel, and other national security officials, and especially military personnel are sent beyond the bounds of our own body politic and its laws and authorities. These personnel constantly accept risks on behalf of the larger community.

Lamb’s book describes the U.S. response to the Mayaguez seizure, recounted in blow-by-blow detail, as confusing and clouded by the chaotic invasion of the unexpectedly heavily defended Koh Tang Island off Cambodia’s southern coast, where American officials wrongly believed that Mayaguez crewmen were being held. More than 240 members of the 2nd Battalion, 9th Marine Regiment, prematurely assaulted Koh Tang in Air Force HH-53 helicopters and fatally less-armored Marine CH-53 choppers.

Several hundred determined Khmer Rouge defenders (the enemy’s unexpected high numbers yet another CIA intelligence failure), well-armed with heavy weapons, overwhelmed the American assault forces on Koh Tang’s impossibly narrow east and west landing beaches. The Marines’ mantra, “Leave no man behind,” was put aside as an impossibility. Suffering heavy casualties and susceptible to many more, the Marines left their fallen comrades’ bodies on the island and, unconscionably, abandoned three live Marines: Lance Cpl. Joseph Hargrove, Pfc. Gary Hall and Pfc. Danny Marshall—all brutally executed by their Khmer Rouge captors.

Despite popular misconceptions that presidential “micromanagement” caused the fiasco that resulted in the number of rescuers killed being higher than the number of people rescued, Ford gave military commanders wide leeway in planning, coordinating and implementing the rescue operations, Lamb reveals. But the U.S. military effort was amateurish and badly botched. The Mayaguez rescue operation—and five years later the almost criminally incompetent failed April 1980 joint military Operation Eagle Claw to rescue American hostages in Iran—ushered in the much-needed 1986 Goldwater-Nichols Act fundamentally reforming U.S. joint military operations.

Readers looking for a dramatic, compelling story of the Mayaguez action will find Lamb’s account, while superb, also somewhat “dry.” Lamb’s research, however, is impeccable, and his conclusions are spot on:

Only good fortune and the skill, initiative, and valor displayed by US forces prevented much higher casualties and a complete disaster; … it is clear US leaders pursued geostrategic goals and that they successfully conveyed their deterrent message; and the sacrifices made by US servicemen…might have been avoided, but they were not in vain.