By Evan A. Kutzler

University of North Carolina Press, 2019, $29.95

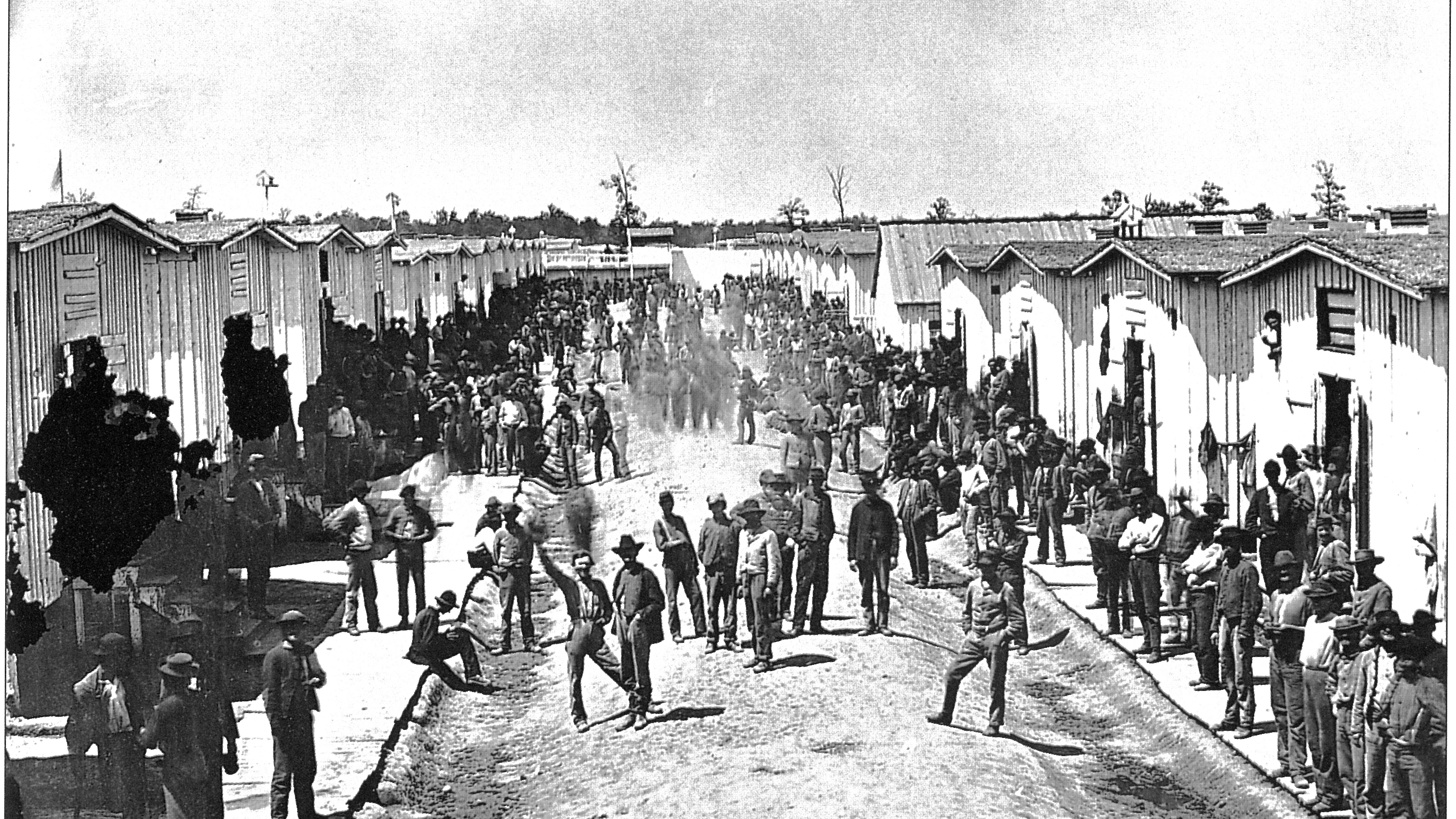

The brutality of the Civil War assaulted the bodies of soldiers in unprecedented severity. It also, according to Evan Kutzler’s idiosyncratic monograph, assaulted their senses, especially those of men incarcerated in Union and Confederate prisons. With time on their hands, these soldiers wrote voluminously about what they smelled, heard, tasted, and felt. Kutzler has read deeply and empathetically into their letters, diaries, and memoirs to bring to light how imprisoned men perceived their environment through the basic human senses. “Sensory perception,” Kutzler posits, “holds the marrow of human experience,” and revealing them presents deeply personal insights into the war’s effect on the men who fought it.

According to Kutzler, prisoners soon realized that to survive captivity and preserve their minds and bodies “meant understanding the more subtle dangers of the sensory environment” every hour of every day. This was a deeply personal battle, and Kutzler carefully refrains from drawing generalized conclusions about living conditions and the quality of treatment at specific prisons. “Learning from and adapting to unfamiliar sensory environments was essential to survival everywhere,” he concludes.

Kutzler begins his account at night because “darkness disoriented and reoriented the perceptions, expectations, and relationships of imprisoned men.”Night heightened the quality of the nonvisual senses. The sounds of men sleeping and suffering pain in close quarters, the scratching of nocturnal vermin, the regular tramp of camp guards, and even the absence of sound affected the times and quality of sleep and other familiar daily routines. “By listening, smelling, and feeling, men engaged in an interpretive process that gave meaning to the phenomena around them and taught them what to expect in the future.”

Prisoners had to breathe, and each breath brought a multiplicity of odors, mostly foul and inescapable. Cramped quarters, poor sanitation, and indifferent personal hygiene made “bad air” omnipresent but rarely rectified by prison officials due to apathetic management, poor camp layouts, cheap building materials, and, particularly in the South, rotten food. These conditions led many prisoners to experience anosmia, a temporary loss of the sense of smell.

From the war’s earliest days, lice became part of the prison landscape and caused men to feel their bodies in uncomfortable, often embarrassing ways. Keeping clean in prison was impossible. “Lice transformed the feeling of prison life by pushing men to accept different measures of cleanliness,” and “despite the prevalence of a soap ration in the North, neither Union nor Confederate officials made sufficient accommodations to support washing and bathing.” The prevalence of lice knew no social boundaries and changed male rules regarding touch, smell, and personal hygiene.

There was no escape from the soundscape of prison and the cacophony of noise. “When prisoners listened,” Kutzler concludes, “they sought to understand their present, reconcile it with their past, and predict their future.”

He uses David Kennedy, a prisoner in Andersonville, as an example of someone whose listening “was a selective process that winnowed noise, and he picked out sounds that mattered most to him.” There were human sounds—groans of sick men, communal reading and game playing, music and singing, orders from the guards, and rumors of changing military situations, exchange, and freedom. There were also sounds from outside the prison, each with its own meaning, including church bells, trains, birds, and the wind. At Andersonville, the Union prisoners could hear slaves singing as they worked and it gave them strength and “reminded prisoners of the enslaved people’s humanity as well as the ideological goals of emancipation.”

Kutzler closes the book with an unusual personal experience. He spent five nights alone at the guest cottage at Andersonville, located between the prison and the cemetery. Understanding that his circumstances were different from the men who had been imprisoned there, Kutzler experienced many of the same sensory experiences. “Walking along the deadline at Andersonville boosted my confidence that sensory perception provides historians with a way to amplify particular lessons from related fields, particularly about the relationship between humans and the natural world.” –Gordon Berg

[hr]

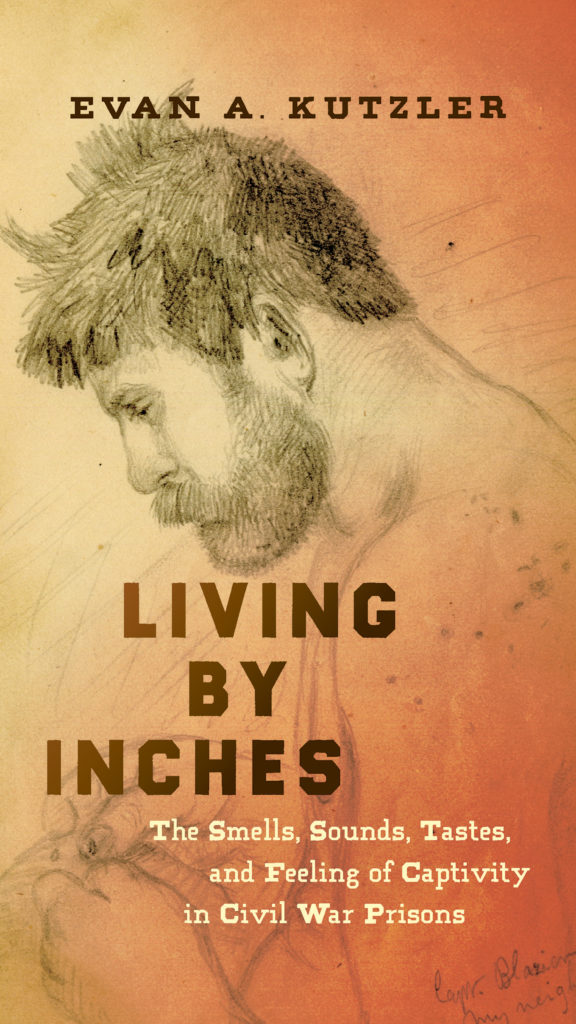

Edited by Karen Stokes

Mercer University Press, 2019, $35

The Blackford boys of Fredericksburg and Lynchburg have long held the trophy for being the most fertile literary clan in Confederate Virginia. Five of them, serving in five different military branches, all left valuable written material. This wonderful new book about the Haskells of South Carolina, added to two earlier published memoirs, puts them on equal footing with the erudite Blackfords.

Six of the seven Haskell brothers fought in Virginia. Two were killed, one as he led a famous charge against Seminary Ridge at Gettysburg; wounds dreadfully maimed two others. Two Haskells were colonels; two others served in important staff billets. The Everlasting Circle prints correspondence from all seven, and also a substantial volume of letters from the women in their family.

Editor Karen Stokes does a marvelous job. She identifies virtually every individual mentioned in the letters, even if only obliquely, and sometimes skillfully figures out someone alluded to despite no name given in the original. Readers will find material of special interest throughout; probably the most important content are the descriptions and assessments of fellow Confederate officers. The Haskell boys spoke without inhibition about their colleagues of all ranks—often including sharply pejorative comments but usually tempering the judgment by citing some good quality. Their evenhanded approach makes the negative reports the more believable; these were not chronic carpers of, say, the D.H. Hill stripe.

On General Joseph E. Johnston: “[W]ith all my admiration for his manly, soldierly character, I never have been able to look upon him as a great General. He is without exception the worst manager of an army among our chief generals.” Colonel Henry Coalter Cabell was “a great deal worse than no one at all,” and Major Mathis W. Henry, while “very gallant” and “brave,” was “idle and dissipated” and guilty of “inertness and bad management….” Brigadier General James Conner was “not at all an agreeable companion,” an “egregious snob,” and afflicted by “small restless ambition.”

Descriptions of E.P. Alexander rarely stray far from praise. Colonel A.C. Haskell’s glowing letter home in August 1863 called him “a singular & rare combination of gentleman, soldier and scientific man, all of a very high order.”

This is a magnificent book, impeccably edited and full of rich material. Sixteen full-page illustrations, some never before in print, illuminate the narrative. –Robert K. Krick

[hr]

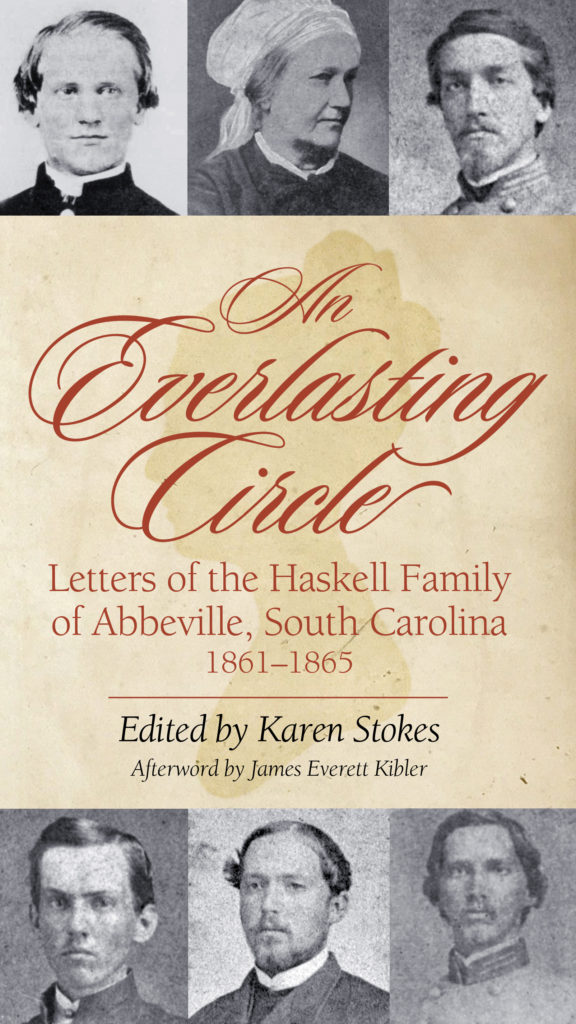

By Ronald D. Kirkwood

Savas Beatie, 2019, $34.95

In “Too Much for Human Endurance,” journalist and Spangler Farm expert Ronald D. Kirkwood brings to light many stories of the Union hospitals that were established on the George Spangler Farm, which was located northeast of the Round Tops between Taneytown Road and Baltimore Pike. This is the first full volume written about the role the Spangler Farm played during the Battle of Gettysburg, as well as the ordeal the family experienced during the three-day fight in July 1863.

George and Elizabeth Spangler and their four children watched helplessly as two hospitals were established on their land, the massive 11th Corps hospital centered in their barn and the small but still busy 1st Division, 2nd Corps hospital at the Granite Schoolhouse located on a small parcel of land within the farm’s boundaries. In addition, Union troops advanced over the property and also bivouacked there, trampling crops and tearing down valuable fencing. The author successfully details information about Army of the Potomac medical personnel and nurses who toiled in the hospitals, and how the Spangler’s farmland played a crucial role during the engagement, and he provides gripping stories about the individuals who were treated, and in some cases passed away, at this farm’s hospitals. No other farm on the battlefield had such an important impact on the Union victory.

Kirkwood has served as a volunteer at Gettysburg since 2013 and is well-versed to provide outstanding stories and anecdotes about many soldiers, including Confederates, who spent time at the Spangler site. Some of those names are very recognizable officers. Confederate Brig. Gen. Lewis Armistead, subject of an informative and remarkable chapter, died on the farm. In addition, such luminaries as Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock, Brig. Gen. Samuel K. Zook, Brig. Gen. Francis Barlow, and Colonel Edward E. Cross were taken to the Spangler Farm. But Kirkwood does not neglect common soldiers, and readers will learn about Private George Nixon III, great-grandfather of President Richard M. Nixon, and other stories about members of the rank and file at the Spangler site. The roles played by a number of nurses also allows the prose to come alive.

Savas Beatie has produced another outstanding tome. Kirkwood’s writing is excellent and his research extensive, and buffs will not be able to put this book down. The maps included are outstanding and enhance the reading experience. The six appendices are alone worth the cost of this outstanding new narrative. Each chapter ends with a “Spangler Farm Short Story” that provides human interest and adds interesting details. You will want this book handy when you visit the battlefield. –David Marshall

[hr]

By Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez

LSU Press, 2019, $55

From the moment of his capture in May 1865, the question of what to do with Jefferson Davis bedeviled Union leaders. The suspicion that he played a role in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln and bore responsibility for the horrors of Andersonville seemed to assure harsh punishment.

Treason on Trial details how, over the nearly four years that followed, indecisiveness and incompetence, political self-aggrandizement, and evolving tensions between conflicting desires for vengeance and reconciliation led to the failure to hold Davis accountable for his role in the war.

Unlike Lincoln, whom Ulysses Grant believed “wanted Mr. Davis to escape, because he did not wish to deal with the matter of his punishment,” Andrew Johnson was eager to see Davis convicted of treason. Robert Icenhauer-Ramirez, a practicing lawyer and historian, is a somewhat prolix stylist who sometimes repeats himself. But his careful narrative leads readers through the constitutional arguments and legal maneuvers that shaped the efforts, ultimately unsuccessful, to prosecute the Confederate president.

Like many high-profile cases, the trial of Jefferson Davis was to involve teams of lawyers. Two leading lights of the New York Bar—William Evarts and Charles O’Conor—were to be respective heads of the prosecution and the defense. Among the others who would play roles were a former Massachusetts governor; Richard Henry Dana Jr., author of Two Years Before the Mast; and Lucius Chandler, a federal attorney in eastern Virginia who would prove overmatched by the case’s legal demands.

By late 1865, the conviction and execution of Henry Wirz, commandant at Andersonville, seemed proof positive for many that Davis was also guilty of the mistreatment of Union prisoners. And, argues the author, “[T]he United States government…[would never] again have a court, a team, and evidence ready at the same time to try Jefferson Davis.”

By late 1865, the Radical Republicans were questioning why Davis had yet to be tried, but concern that a trial in Richmond might result in an acquittal led prosecutors to repeatedly reschedule trial dates. And Chief Justice Salmon P. Chase, set to share duties as presiding judge, determinedly dodged the case, convinced it would harm his chance to become the Democratic presidential nominee in 1868.

After two years of imprisonment at Fort Monroe, Davis was transferred to civilian control in May 1867 and shortly thereafter was released upon payment of a $100,000 bond guaranteed by, among others, Horace Greeley. When Evarts, the prosecution’s lead attorney, agreed to help defend Andrew Johnson in his impeachment trial a year later, all likelihood that Davis would be brought to trial evaporated. Not until February 11, 1869, nearly two months after Andrew Johnson issued a Christmas Day proclamation of universal amnesty, did the federal government dismiss the indictments against Davis. The failure to prosecute him as a traitor, Icenhauer-Ramirez argues, fed belief among unreconstructed Southerners that Davis’ belief in secession’s constitutionality was legitimate. Davis and his wife would spend the rest of their lives contending he had been wrongly accused of a crime.

Icenhauer-Ramirez closes with a conclusion worthy of further discussion. “Jefferson Davis was not tried because the leaders of the United States were noble, principled men not bent on vengeance,” he writes. “[They]…harbored no doubt that Davis deserved to hang for the treason he had committed. But in their eyes, the United States was imbued with an exceptionalism…[possessing a] penchant for mercy, when…other nations would have sought revenge.” –Rick Beard

[hr]

Thirteen Days to Washington

By Ted Widmer

Simon and Schuster, 2020, $35

On February 11, 1861, Abraham Lincoln boarded a train in Springfield, Ill., heading to Washington, D.C. “Let us confidently hope that all will yet be well,” he told friends and well-wishers, and though his thoughts doubtless focused on the crisis of union, he may as well have been alluding to the treacherous journey ahead. As Ted Widmer brings to life in this learned, lyrical book, the remarkable passage took 13 days, 18 rail lines, and traversed 1,904 miles across eight states—his safety never assured. By the time Lincoln arrived, both the nation and the man had been transformed.

Widmer diligently sorts through the “kaleidoscopic confusion” about what truly occurred—the story, for example, where a grenade was discovered inside a carpetbag in Lincoln’s car as he prepared to leave Cincinnati on February 13. Widmer suggests this is authentic, writing that security around the president-elect continued to tighten and that Lincoln (given the code name “Nuts” by Allen Pinkerton) quietly entered Washington on February 23.

At times, Lincoln was in danger of being crushed by fervent crowds. Not every speech succeeded. Some drifted too far into policy whereas the people craved humor and homespun wisdom. He erred in Pittsburgh by declaring “there is really no crisis except an artificial one” (remarks denounced by Henry Villard as “ignorant twaddle”), but reached Olympian heights at Philadelphia’s Independence Hall when he spoke with self-described “deep emotion” and declared, “I have never had a feeling politically that did not spring from the sentiments embodied in the Declaration of Independence.”

Lincoln was strengthened even as the trek drained him. His speeches and physical presence, Widmer writes, “shored up America’s flagging belief in her institutions.” Democracy would survive because Lincoln survived.

Widmer’s opus aspires as much to literature as to history. Each chapter opens with an epigraph from Homer’s Odyssey, placing Lincoln’s travels within the long literary tradition of the heroic quest. Quotations from Moby-Dick also appear, and it is worth noting that Lincoln and Herman Melville’s Ishmael both suffered from the “hypos.” Ishmael survived to tell his tale; Lincoln did not. Fortunately, we have this book to tell it for him. –Louis P. Masur

[hr]

By Thavolia Glymph

UNC Press, 2020, $34.95

Civil War scholar James McPherson maintains that “revision is the lifeblood of historical scholarship” because “history is continuing dialogue between the present and the past.” As she shows in her new book, Thavolia Glymph fully understands what McPherson professes.

Her insightful The Women’s Fight allows Civil War–era women to stand taller and more clearly defined. Here, Glymph looks at the “women’s fight across the divides of space, race, and class as they moved into each other’s worlds as slaveholders, black and white refugees, missionaries, agents of freedman’s aid societies, abolitionists, Unionists, and freedom seekers.” She succeeds in connecting these myriad strands because “the spaces in which women live during…war are no more inviolate than the spaces in which men fight, and the two are never completely cordoned off from each other.”

Southern white women, for instance, “fought a war for which they were ill prepared.” Union occupation of vast swaths of Confederate territory uprooted slave-holding women from their pampered, plantation-centered lives and made them homeless refugees, forcing them into often uncomfortable relationships with poor rural and urban working-class women whose values and daily necessities they never shared and rarely understood. “The presence of white women on the road as refugees,” Glymph concludes, “thus undermines one of the most fundamental tenets of proslavery thought and a rationale for mobilizing Southern white men.”

For black women in the South, the war promised the possibility not only of emancipation but also new definitions of home, family, and citizenship. Often in the face of rampant Northern racism and paternalistic objectification, black women in the South “made a difference, a difference in helping to fuel transformations in Union war aims, the conduct of the war, and in contributing to the making of wartime freedom.”

Glymph carefully documents that throughout the war, despite ill treatment by slaveowners and many Union emancipators, these courageous women “mobilized to support the Union cause and emancipation, taking their stand on the antislavery ground they had sowed for decades as enslaved women.” –Gordon Berg

[hr]

By Gregory A. Mertz

Savas Beatie, 2019, $14.95

After the loss of Fort Donelson in February 1862, Confederate General Albert Sidney Johnston organized available forces for a strike on Union Maj. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s army that he hoped would restore both the Confederacy’s situation in the Western Theater as well as his personal reputation.

His strategy was sound, but his planning was not. Instead of concentrating his own forces before striking at the enemy camped at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., Johnston moved his corps in piecemeal. He also placed himself among his front-line forces, a brave but shortsighted gesture that cost him his life at a critical moment.

The two-day Battle of Shiloh, a Union victory, would produce 23,000 casualties and shock the divided nation. In Attack at Daylight and Whip Them, Gregory A. Mertz, a 37-year NPS veteran, examines the battle and provides a parallel resource for following and interpreting the monuments spread across Shiloh National Military Park.

From the first page to the last, this is a great read. –Thomas Zacharis

These reviews appeared in the July issue of America’s Civil War.