By Robert W. Black

Pen and Sword, 2019, $32.95

Colonel Black, a decorated U.S. Army Ranger of the Korean and Vietnam wars, is author of several Ranger histories, the latest focused on the American Civil War. Rangers have a venerable legacy in American military history, going back to colonial times, combining Native American hit-and-run infantry tactics with scouting for intelligence and using accurate, long-range rifles. The author aptly observes, “Terrain is the workplace of the ranger,” which was certainly true for the 72 Union and 270 Confederate ranger units deployed during the Civil War. Tactics were also similar, but now largely undertaken by highly mobile mounted men, armed with multiple revolvers, with many on the Union side using Spencer repeating rifles.

The strength of this book is the focus on operations in the area of mountainous West Virginia and the lush Shenandoah Valley, recounting many colorful, almost James Bond–like characters such as Turner Ashby and Harry Gilmor for the South and Charles Webster and Henry Young for the North. Black analyzes the Confederate Congress’ 1862 Partisan Ranger Act that authorized armed irregular attacks on the United States, including a profit motive via sale of looted goods. This attracted tough adventurers but also a criminal element, with their resulting branding by the North as “horse thieves” and “bushwhackers.” Union units tended to be more conventional or reactive, though becoming more lethally skilled as the war progressed. Rangers on both sides proved adept in support of regular units at major battles such as Antietam or Gettysburg and were especially effective strike forces away from the front lines, often literally bringing the war’s chaos to civilian doorsteps.

Yank and Rebel Rangers is a worthy effort but would have benefited from better editing. The chapter organization is haphazard at best, ranging (no pun intended) from one page to more than 50 pages. Some chapter topics are questionable, with only one obligatory effort made in writing about anything outside West Virginia and Virginia, while others, especially those on Gilmor and Young, would make excellent book topics by themselves. There are also occasional prose redundancies. Endnotes, bibliography, and an index are welcome, but, sadly, no maps or illustrations, were included, which would have greatly enhanced the reader’s understanding of a specialized work of this nature. Finally, Yank and Rebel Rangers can be usefully read as a supplement, but in no way superior to Robert P. Broadwater’s Civil War Special Forces: The Elite and Distinct Fighting Units of the Union and Confederate Armies (2014). –William John Shepherd

Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum, Indianapolis, Ind.

At the tail-end of the 19th century, Eli Lilly, colonel of the 18th Independent Battery, Indiana Light Artillery, and, later, the head of a chemical corporation and philanthropic leader, worked tirelessly to raise funds for the construction of a Soldiers and Sailors Monument in downtown Indianapolis. The magnificent memorial was dedicated in 1902.

In 1999, the Colonel Eli Lilly Civil War Museum opened inside the popular site. The 9,000-square-foot converted space underneath the monument, housed artifacts, videos, and design elements paying tribute to the story of the common soldier: from muster in until war’s end. Special attention, of course, was paid to the story of the monument’s champion, Eli Lilly.

In 2017, failed weather seals on some of the monument’s skylights led to excessive moisture within the museum. Experts swiftly discerned that the rise in humidity levels would create a potentially adverse environment, threatening the museum’s collections. A new home, either temporary or permanent, quickly had to be found.

Staff from the nearby Indiana War Memorial came to the rescue and most items were transported to IWM collections storage in just 30 days.

The collections manager concentrated on the packing and transport of approximately 100 objects ranging in size from a small sewing kit, to a Gettysburg cannon ball imbedded in a tree trunk, to an artillery cannon. This was no small feat. Each case was inventoried. Each artifact was tagged and then photographed to document condition. Next, items were packed so that each exhibit case’s artifacts remained together.

The cannon provided more challenge. Since it is technically federal property, a federal entity was required to move it. A 15-member National Guard artillery detachment dismantled the cannon, put it in a transport vehicle, then reassembled the weapon at its new home.

The move created a unique opportunity and members of the staff of both museums decided that the “best of the best” of both the Eli Lilly and IWM collections would be integrated into a new Civil War exhibition at the IWM. IWM’s collection includes approximately 350 Civil War battle flags, along with a large variety of ordnance. Eli Lilly’s Civil War collection contains artifacts from both the home front and battlefield, including the colonel’s frock coat, as well as a 3-inch cannon from his 18th Battery, Indiana Light Artillery.

The new exhibits will be artifact-oriented with a focus on the stories of individual Hoosier soldiers. In addition to Eli Lilly’s story, you will see the story of George Banks, Medal of Honor recipient and color-bearer of the 15th Indiana Infantry, along with a flag from the 15th Indiana. Several more flags in the IWM’s expansive collection have been conserved and mounted in new cases. Flags from future president Benjamin Harrison’s 70th Indiana Infantry and Lew Wallace’s 11th Indiana Infantry will also be featured, as well as a flag of the 28th Regiment, United States Colored Troops—the only African American regiment organized in Indiana.

One of the most intricate flags on display will be that of the 13th Indiana Infantry, nicknamed the “Tiffany Flag,” on which the state seal is embroidered not painted, as was typical of the day. More than 30 flags have been conserved, and more are in process. (To view a complete inventory of the flag collection, go to bit.ly/IndianaCWFlags).

Visitor favorites, including original, never-before-seen Civil War muskets, rifles, revolvers, and swords will also be on display. Also examined through exhibit and interpretation will be Oliver P. Morton’s tenure as Indiana’s Civil War governor.

To date, much progress has been made. The Civil War exhibition design is near the end of its planning stage. –Terri Sinnot

For tour information, call the IWM at (317) 233-0528. To receive the most up-to-date information, call (317) 232-7615. Go to IndianaWarMemorials.org to learn more.

The Indiana War Memorial Museum is located at 55 E. Michigan St., Indianapolis, IN 46204. Hours of operation: Wednesday–Sunday, 9 a.m.–5 p.m. The museum is closed on Monday and Tuesday and on all national and state holidays except Memorial Day and Veterans Day.

By Sidney Blumenthal

Simon and Schuster

2019, $35

Sidney Blumenthal’s absorbing third volume of his “The Political Life of Abraham Lincoln” series opens with the inauguration of Franklin Pierce and closes with Lincoln’s election. Every student of American history can recite the events of those years that brought the nation toward dissolution: principally the Kansas-Nebraska Act, the formation of the Republican Party, Senator Charles Sumner’s caning in the U.S. Capitol, the 1857 Dred Scott decision, violence in Kansas, and John Brown’s Harpers Ferry raid.

Blumenthal narrates all these stories with abundant details that take readers into political backrooms and public arenas. He is willing to leave Lincoln offstage for scores of pages at a time. The result in Part One, “The Present Crisis,” is a textured portrait of the politics out of which Lincoln rose and memorable descriptions of countless figures. Blumenthal is not afraid to offer his judgment, and what he doesn’t say, he allows sources to vocalize.

The heart of All the Powers of Earth is the Lincoln-Douglas debates, and they read like a Shakespearean play. Both men had abundant ambition. Lincoln, however, never surrendered principle to desire. Not so for Douglas. His Kansas-Nebraska Act was intended to win the support of Southern Democrats. It initially accomplished that goal and also provoked something unintended: It reignited Lincoln’s passion for politics.

Blumenthal shows how, in the Lincoln-Douglas battles, “local politics were waged for national stakes.” The debates made Lincoln a national figure (he made sure of it by having the text published afterward). Although Douglas narrowly won the Senate election, his responses to questions posed by Lincoln at Freeport, Ill., in which Douglas admitted a right for settlers to exclude slavery prior to the formation of a state constitution, cost him among Southern supporters.

“The fight must go on,” Lincoln wrote after his defeat. For the next two years, he carefully managed his political rise, culminating in the powerful Cooper Union Address in which he showed that the Founding Fathers were arrayed against slavery and offered a stout defense of Republican Party principles.

Lyman Trumbull, who had benefited when Lincoln stepped aside from Senate consideration in 1855, remarked that Lincoln “was by no means the unsophisticated, artless man many took him to be.” His artfulness is on full display here, and it delivered him to the presidency. –Louis P. Masur

By Michael P. Rucker

New South Books

2019, $28.95

It should be said right off the top that this is not a bad book, but neither is it great. Ostensibly a biography, it contains long sections where the subject and his efforts are not referenced or minimally so. It is somewhat of a narrative of the war’s course and the campaigns in which Edmund Rucker was present and only secondarily recounts his exploits in those same campaigns. There is relatively little early life biographical information and even his postwar career in steel and real estate and his railroad partnership with Nathan Bedford Forrest is covered in two short chapters.

Edmund W. Rucker was a second-half-of-the-war cavalry brigade commander serving under Forrest, so a biography would be most welcome were it somewhat more extensive than this. Before joining Forrest, Rucker’s most notable experience was as a battery commander in the Island No. 10/New Madrid Campaign in early 1862, followed by onerous conscription duty in East Tennessee to which the title refers. His later service with Forrest included the overwhelming victory at Brice’s Cross Roads in June 1864, the Johnsonville Depot Raid in Tennessee, and John Bell Hood’s autumn campaign, which resulted in Rucker’s wounding at Nashville, amputation of an arm, capture, and incarceration at Johnson’s Island. Although exchanged in early winter 1865, his military career was at an end.

Author Rucker, a distant relative of his subject, may have been a one-time Civil War tour guide, with his brother, yet his style is not that of a historian—although the book does include footnotes, a bibliography, and several largely relevant appendices. His writing is not necessarily scholarly, but instead is aimed at the general public. There are also too many of the author’s personal characterizations of generals and others as being inept, incompetent, or lacking in military leadership skills (although certainly accurate in the cases of Gideon Pillow and Leonidas Polk).

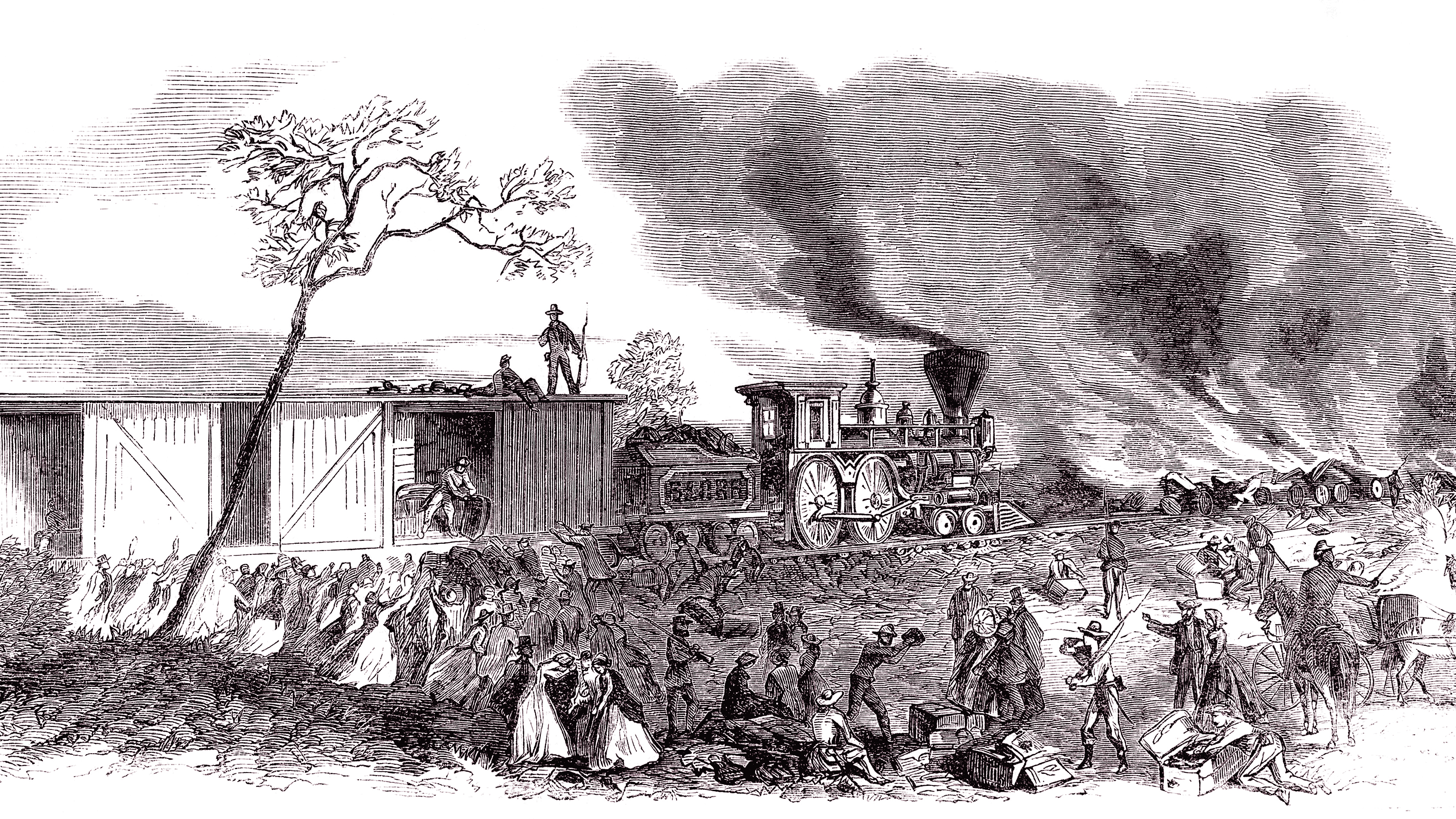

Fortunately, along with 11 maps, the book is replete with photographs, drawings, and illustrations from the Library of Congress, the “Battles and Leaders” series, Harper’s Weekly, Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, and other sources.

With fairly short chapters, this is an easy to read book on a potentially interesting figure, yet readers need to be aware of its shortcomings. –Stuart McClung

By Kevin M. Levin

University of North Carolina Press, 2019, $30

Kevin Levin’s excellent study dismantles arguments about black Confederates in a manner so comprehensive and compelling that it leaves little room for doubt from all but the most fervent Lost Cause disciples. An educator with a popular website, Civil War Memory, Levin examines the long-acknowledged presence of camp slaves with the Army of Northern Virginia, noting it was likely that as many as one in every 20–30 soldiers was accompanied by an enslaved man. At Gettysburg, he writes, the 10,000 or so camp slaves with Lee’s army were essential to its effectiveness, but they certainly did not fight.

Indeed, recruiting slaves to fight was vociferously opposed by most Southern leaders, including Maj. Gen. Howell Cobb of Georgia, who wrote: “The moment you resort to negro soldiers is the beginning of the end of the revolution. If slaves will make good soldiers, our whole theory of slavery is wrong.”

Although camp slaves were welcome at many Confederate reunions after the war, Levin argues that recognition of their presence at these affairs only bolsters the loyal slave narrative that is so central to the Lost Cause myth. Levin also insists that claims of blacks serving as Confederate soldiers is a fairly recent phenomenon. “Unrecognizable to earlier generations of Southern sympathizers,” this fiction was likely a response to popular documentaries such as “Roots” and Ken Burns’ “Civil War.”

Searching for Black Confederates should be required reading for anyone interested in how Americans remember the Civil War. Acolytes of the Lost Cause will no doubt find little to like. But for anyone else, Levin’s powerful indictment should represent the death knell for the Civil War’s most persistent myth. –Rick Beard

By Jack Dempsey

The History Press, 2019, $21.99

Jack Dempsey seeks to fill a gap in literature on the war, namely the lack of a published biography of Union Maj. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams. In addition to serving as a general officer in some of the war’s most important campaigns, Williams was a keen observer of men and events and had few compunctions about sharing his experiences and opinions with his family.

Due to his experience in Michigan’s militia, Williams was able to enter the Union Army at a fairly high rank despite lacking a West Point education. As a division commander in 1862, he marched up and down the Shenandoah Valley with Nathaniel Banks and had the thankless task of trying to hold off Stonewall Jackson’s attack at First Winchester. His command then delivered the attack that nearly brought Banks victory at Cedar Mountain and, except for the brief time Joseph K.F. Mansfield was on the field, it was Williams who led the 12th Corps through some of the hardest fighting at Antietam.

Williams also saw significant action at Chancellorsville and Gettysburg, and during Sherman’s March to the Sea and Carolinas Campaigns.

In this highly readable account, Dempsey is unabashedly admiring of Williams, though by no means unreasonably so. Readers seeking a complete account of Williams’ military career, as well as his notable prewar life and postwar exploits, will find this a useful and interesting study. –Ethan S. Rafuse

These reviews appeared in the January 2020 issue of America’s Civil War.