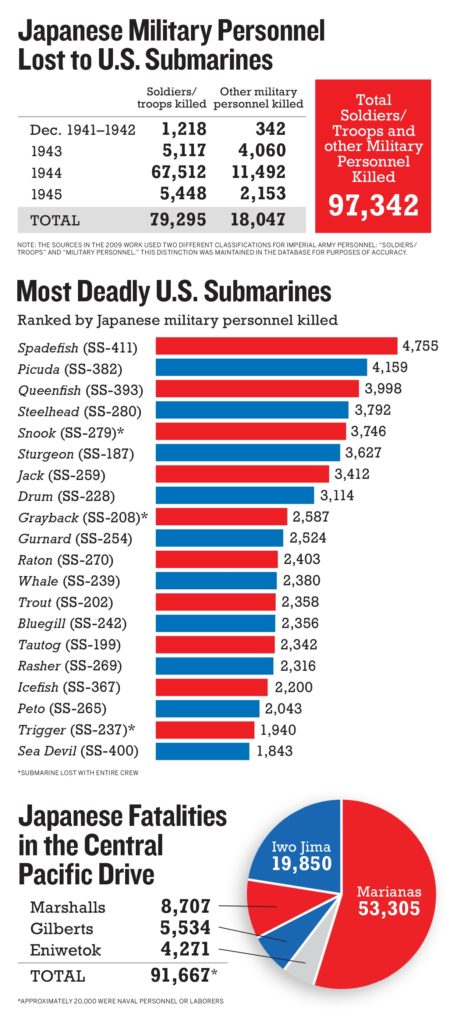

IT’S A STORY more than 75 years old, but revealed in detail here for the first time. Simply stated, the contribution of American submarines in the Pacific War was far greater than previously recognized. Indeed,American undersea craft killed at least 97,342 Japanese soldiers—more than the Marine Corps and the U.S. Army did in the central Pacific drive from Tarawa in November 1943 to Iwo Jima in February–March 1945. The grand total may prove to be higher still. Why this contribution remained obscured for so long is an intriguing storyin itself that requires some background.

The standard narrative about U.S. submarines’ performance emerged shortly after the war, when the U.S. Joint Army-Navy Assessment Committee (JANAC) studied the causes behind the loss of Japanese naval and merchant vessels. Despite some gaps in the study—it was limited to merchant vessels over 500 tons, for example, and missed some larger vessels—the assessment still serves as a sturdy reference point. By JANAC calculations, American forces sank 611 Japanese naval vessels, totaling 1,822,210 tons;and 2,117 merchant vessels, of 7,913,858 tons. Of that, submarines contributed a huge part, accounting for 201 naval vessels (540,192 tons) and 1,113 merchant vessels (4,779,902 tons)—or about 33 percent of naval vessels by number and 30 percent by tonnage, and 52.5 percent of merchant vessels by number and 60 percent by tonnage.

For decades, published histories, notably Clay Blair’s monumental 1975 work Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War Against Japan, mentioned instances in which many Japanese soldiers perished in some of those sinkings. But the full story remained concealed because JANAC and the other sources from which Blair and others worked rarely included figures on losses among the ship’s crews or human cargo—predominantly Japanese troops.

Then in 2009, John D. Alden and Craig R. McDonald published a revised version of United States and Allied Submarine Successes in the Pacific and Far East During World War II. Alden’s original edition had appeared in 1989. He was a World War II submariner himself and the author of a still-standard 1979 work on the development of the World War II U.S. “fleet” submarine. What distinguished this updated edition was the addition of 321 pages of data that McDonald, a programmer analyst, had developed, incorporating a trove of new detail about crew and passenger losses from a translation of Japanese sources by independent researcher Erich Mühlthaler. One day several years later, as I skimmed over entries for 1944, it struck me for the first time that a great many more Japanese soldiers had died in U.S. submarine attacks than had been previously recognized. I suggested to Alden that he try to total the losses of Japanese soldiers in such attacks and write about it. Unfortunately, Alden died in 2014, leaving the project unfinished.

When I decided to pursue it myself, I quickly realized there was a huge obstacle in getting from the raw data to its ultimate revelation. Alden and McDonald had employed a tabular format, with standard entries that identified the submarine, its target, the results, and other relevant facts. The information on human loss, however, appeared in text running beneath the standard data boxes and, therefore, could not be readily extracted with a few keystrokes.

This is wherean IT businessman with a master’s degree in World War II history, Jay D. Fagel, volunteered to step in to perform the laborious but essential task of extracting that information and entering it into a program. His background perfectly suited him for this challenge; he created a program specifically for this project, and we collaborated on what data to extract and use.

The numbers collectively tell the story of U.S. submarines’ increasing effectiveness and the toll taken on Japanese soldiers—one best examined by breaking down the campaign by year. The numbers also present a parallel story: the loss of life of Allied prisoners of war and slave laborers serving Japan. They were transported aboard Japanese vessels, exposing them to attack by both American and British submarines. These stories rise to a crescendo in 1944, before radically changed circumstances in 1945 left U.S. submarines with few targets.

December 1941 and 1942

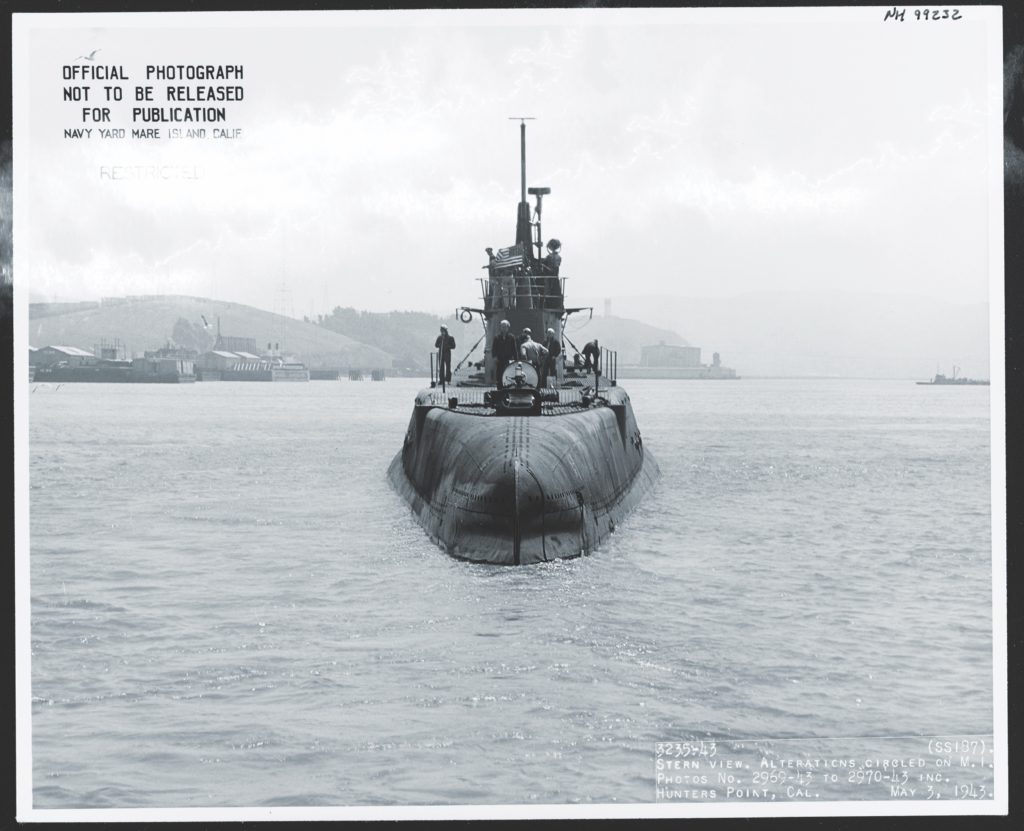

On December 7, 1941, immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the U.S. Navy deployed 56 submarines in the Pacific. These included 12 elderly small “S-boats” of World War I vintage. The rest were large modern fleet submarines developed for the Pacific’s long reaches. From then until the end of 1942, defects beset this modest force, degrading its effectiveness.

The most crippling handicap stemmed from three faults in the standard U.S. Mark XIV submarine torpedo. First, the torpedo would often run under the target without exploding because of a defective depth-setting mechanism. Second, its ultra-secret Mark VImagnetic exploder—designed to detonate when the torpedo was below the target’s hull, where it would inflict more severe damage than a hit on the hull side—typically either did not detonate the weapon at all or caused it to explode before it reached the target. Finally, the torpedo’s conventional contact exploder was fragile and often failed. Ironically, a hit that struck at, or close to, a 90-degree angle—considered near-perfect accuracy—was the most likely to jam the firing pin and fail.

Several other issues also degraded performance. Codebreaking of the time divulged little information for submarines to exploit. The force also learned with embarrassment that it had a “skipper problem”: too many commanders, trained in peacetime environments, proved too cautious and, hence, ineffective. Top command misjudgments sent submarines to patrol off well-guarded major Japanese bases and to attempt interceptions of large combatant vessels—carriers and battleships, for example—that customarily cruised at a speed that outpaced U.S. submarines, making pursuit or attack futile.

Within hours of the Pearl Harbor attack, Admiral Thomas C. Hart, Commander in Chief of the U.S. Asiatic Fleet in Manila, radioed his command to “execute against Japan unrestricted air and submarine warfare”—an order that effectively also initiated the campaign against Japanese shipping. Hart’s fleet included 29 of the 56 American submarines in the Pacific. They constituted the most potent American force not just in the Asiatic Fleet but in the Philippines. But, because of the torpedo and skipper problems, their overall performance was a dismal failure.

Effectiveness improved as 1942 progressed and those two deficiencies began to be addressed. By the year’s end, U.S. submarines had mounted approximately 350 war patrols, sinking about 180 Japanese merchant vessels of 725,000 tons. The only major success against warships was the sinking of the heavy cruiser Kako. In all, Allied submarine attacks killed 1,218 Japanese soldiers and 342 other Imperial Army personnel, for a total of 1,560. Seven U.S. submarines were lost.

Regrettably, 1,903 POWs were also lost in submarine attacks, outnumbering the deaths of Japanese soldiers. The USS Sturgeon, under Lieutenant Commander William L. Wright, inflicted the deadliest single attack in this period. In June 1942, the Japanese herded 845 Australian prisoners of war and 208 civilian internees captured at

Rabaul, New Britain, aboard the Montevideo Maru—a former passenger-cargo vessel impressed into Imperial Navy service. In the first hours of July 1, Sturgeon hit the vessel with one or two torpedoes, and Montevideo Maru sank west of Luzon with all 1,053 Australians and about 20 Japanese crewmembers. Wright had no way of knowing that the vessel was carrying prisoners of war or civilian internees. In subsequent episodes during the war, submarine crews were likewise unaware of which Japanese ships bore friendly human cargo.

1943

This year saw major enhancements to the submarine campaign. In the spring, Allied codebreakers fully mastered Japanese merchant ship codes, yielding critical aid to U.S. submariners. And by September, the defects in the Mark XIV torpedo were largely cured.

The raw figures for 1943 show 350 patrols, almost the same amount as for the 13 prior months, but now accounting for about 335 Japanese merchant ships totaling approximately 1.5 million tons. These numbers are nearly double the figures for December 1941 through December 1942. Bulk commodities reaching Japan fell from about 19.4 million tons in 1942 to 16.4 million tons in 1943. Because new construction of merchant vessels helped offset losses, the net reduction in shipping tonnage was 1.1 million tons. The only major Japanese warship sunk was escort carrier Chuyo. Lost with the troop-bearing ships that U.S. submarines sunk were 9,177 Japanese soldiers; POW and slave laborer deaths totaled 2,172. Fifteen U.S. submarines were lost.

The May 20 sinking of the troopship Bangkok Maru by USS Pollock combined significance with misfortune. The Imperial Navy had deployed its well-trained and equipped 1,559-man 7th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force (SNLF) to Tarawa in the Gilbert Islands. As Tokyo wrangled over island garrison responsibilities, orders came to replace that unit with an ad hoc 800-man Imperial Army battalion. Thanks to a decryption of Bangkok Maru’s routing instructions, Pollock intercepted the vessel, fired effective torpedoes, and sank it in about 90 seconds. About half the battalion was lost. The 400 survivors ended up on Jaluit in the Marshall Islands, where they sat out the war, while the 7th SNLF remained on Tarawa. Because the army battalion had only about half the Imperial Navy unit’s strength and was much less well-armed, had the exchange occurred, Marine losses in the November 1943 Tarawa invasion would certainly have been substantially reduced.

1944

Several factors converged to make this the year of slaughter. Previously, the Imperial Army had primarily focused on fighting on the Asian continent, relegating the Pacific front to secondary status. In January 1943, only 6.5 percent of all Japanese soldiers served in the Solomon Islands and New Guinea fronts. As 1944 began, the Imperial Army finally pivoted its focus to the Pacific Theater. This caused a massive shift—including releasing 12 divisions from the premier Kwantung Army, which had been facing the Soviets in Manchuria, to confront the American advances across the Pacific. These divisions and other units put vastly more Japanese soldiers afloat than at any prior point in the war.

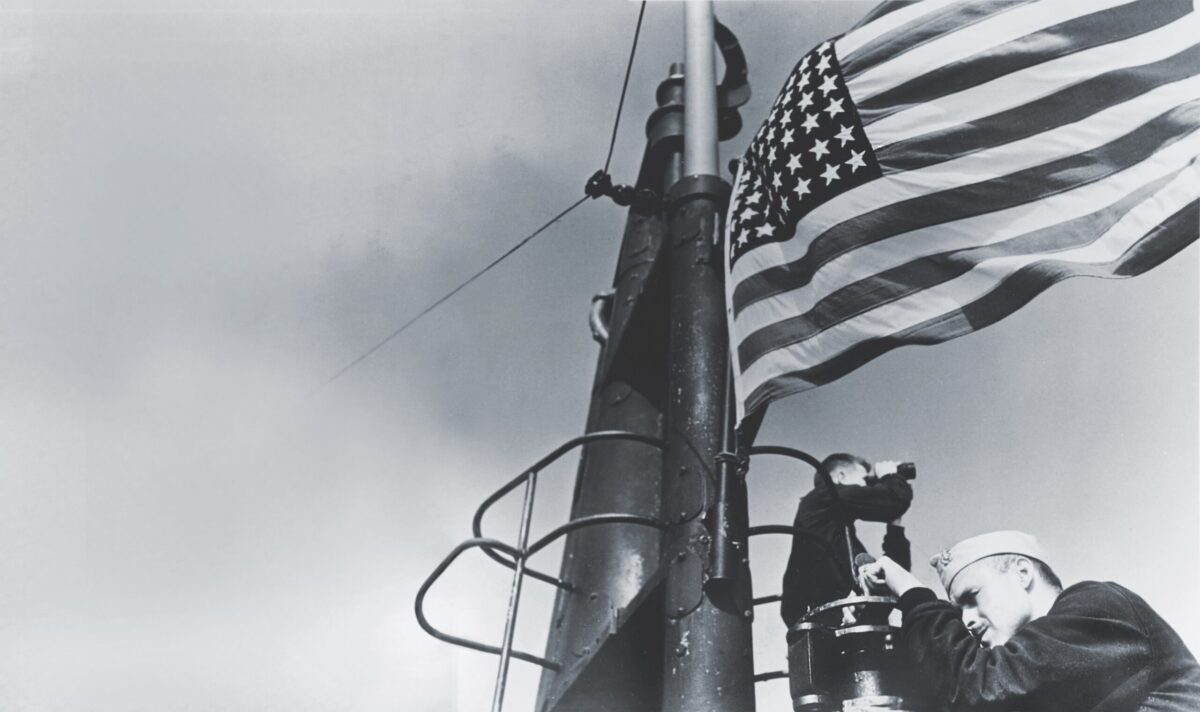

This coincided with the U.S. submarine effort becoming “devastatingly effective,” in the words of Clay Blair. On January 1, 1944, the central and southwest Pacific submarine commands numbered almost 100 excellent fleet boats. Well-seasoned, aggressive commanders and crews comprising mostly patrol veterans exploited new and superior radar and sound sensors and effective torpedoes. Codebreaking, much of it done by now highly proficient women, showered the patrolling submarines with intelligence that set up fatal rendezvous with targets, including many troop-bearing ships.

While the Japanese had far more escort vessels than in prior years, the increase in their numbers did not coincide with an increase in effectiveness. Japanese sensors—especially radar—lagged. And although the number and efficiency of Japanese antisubmarine weapons had increased, they remained inferior to those on American and British vessels.

In about 520 war patrols in 1944, 603 Japanese merchant ships, totaling about 2.7 million tons, fell victim to American submarines—more than in the first 25 months of war combined. Japanese commodity imports plunged from 16.4 million tons to 10 million tons; the net loss of shipping was about two million tons. For the first time, U.S. submarines struck hard at key ships in the Imperial Navy, sinking seven Japanese carriers, one battleship, and two heavy and seven light cruisers. The cost of this triumph was not cheap: 19 American submarines.

With the oceans now packed with Japanese troopships, American submarines inflicted a calamity on the Imperial Army, killing some 79,004 Japanese soldiers. In a remarkable coincidence, the two leading submarines achieved their rank by virtue of sinking two sister ships of the Mayasan Maru class. The Japanese termed these brand-new 460-foot-long vessels “landing craft depot ships.” The loss of one of them, Tamatsu Maru, occurred on August 19, during what was perhaps the most devastating single U.S. submarine assault on a Japanese convoy during the war.

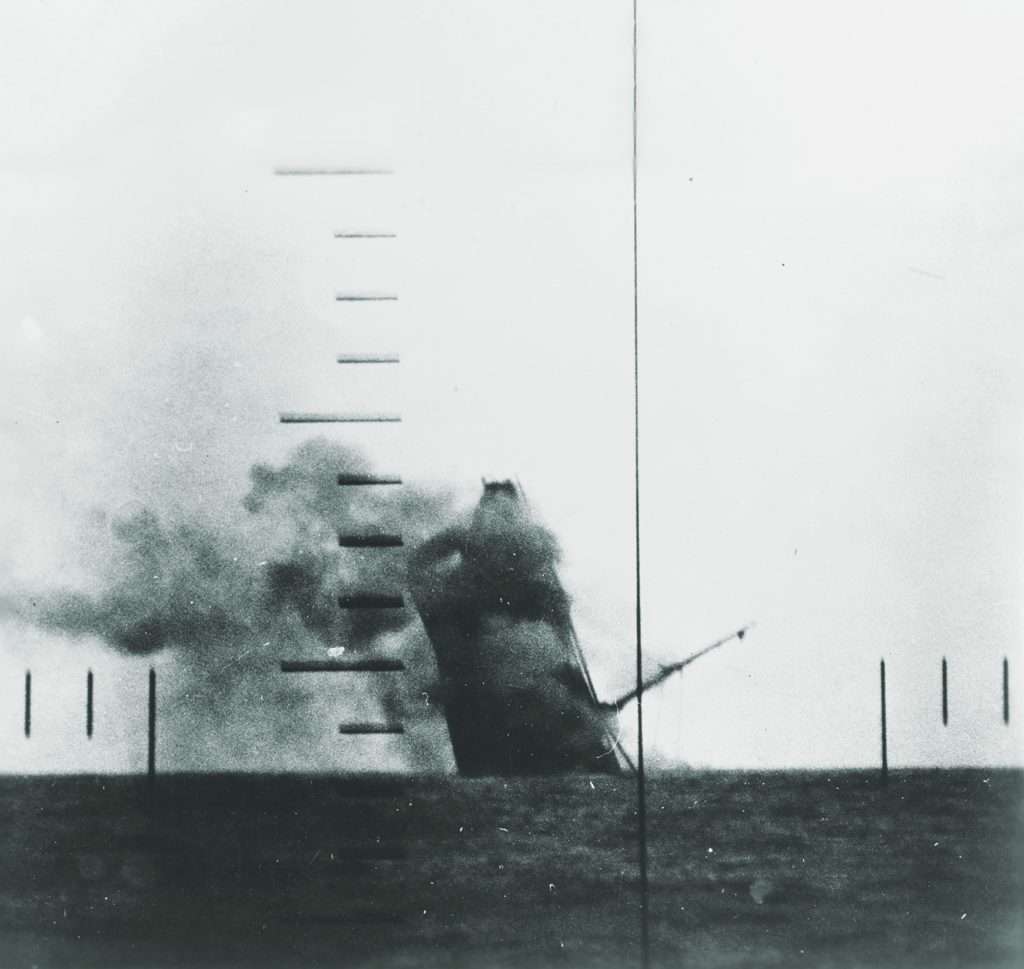

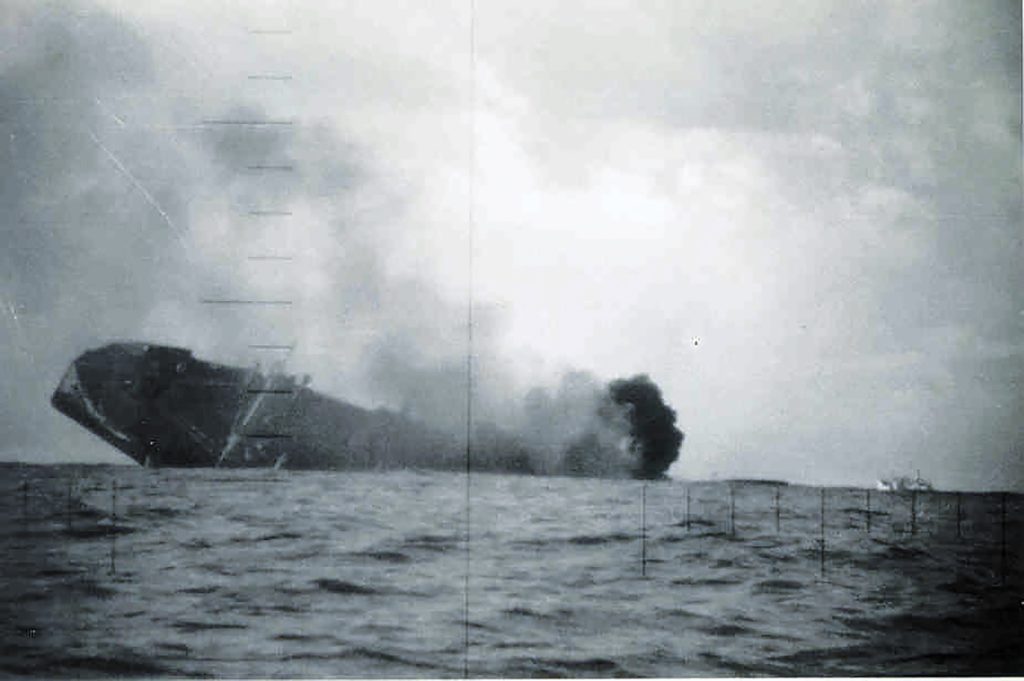

Tamatsu Maru joined a major Singapore-bound convoy, HI-71, originally comprising 17 merchant ships ultimately guarded by three destroyers, nine kaibokan (a relation of the Allied corvette type), and an escort carrier, Taiyo. At 10:22 p.m. on August 18, USS Redfish torpedoed Taiyo. The escort carrier sank with some 850 crewmen. Then, at 11:10 p.m., USS Rasher, running on the surface, scored three torpedo hits on the huge, 17,537-ton transport Teia Maru (the ex-French liner Aramis), carrying 4,795 Japanese soldiers and 427 civilians. The transport sank with 2,316 troops, 275 passengers, and 74 crew members, for a total of 2,665 killed. Shortly after midnight, Rasher torpedoed armed merchant cruiser Noshiro Maru and transport Awa Maru. Both beached themselves to avoid sinking; casualties, if any, are unknown.

At 3:20 a.m. the next morning, USS Bluefish hit fleet oiler Hayasui. The Japanese vessel burst into flames and drifted for a while before finally sinking. (There is no data on its crew or passenger losses.) At 5:10 a.m., Bluefish put three torpedoes into oiler Teiyo Maru. It ignited and then sank stern-first. Down with it went 41 crewmen and 58 passengers.

At 3:33 a.m., Lieutenant Commander Gordon W. Underwood’s USS Spadefish, on its first spectacularly successful patrol, came in at radar depth (submerged except for its periscopes and radar mast) and fired six torpedoes at Tamatsu Maru. Two hit the big landing craft depot ship. Its screws stopped, and it rolled over and sank with 4,755 troops and 135 merchant seamen. That afternoon, one of the convoy’s escorts discovered Tamatsu Maru’s debris field littered with wreckage and about 2,000 bodies drifting in the water. In less than 24 hours, convoy HI-71 had been devastated, with some 8,504 Japanese perishing.

In November 1944, Mayasan Maru,the class’s namesake, formed up in convoy HI-81, bound for Singapore with nine other ships escorted by destroyer Kashi, seven kaibokan, and escort carrier Shinyo. USS Queenfish torpedoed landing craft depot ship Akitsu Maru at 11:56 a.m. on November 15. It sank with 2,093 soldiers of the 2,500-strong 64th Infantry Regiment. Not quite seven hours later, Lieutenant Commander Evan T. Shepard’s USS Picuda torpedoed Mayasan Maru. The huge landing craft depot ship took the plunge in about two and half minutes in rising seas. Losses came to 3,187 troops from the 23rd Infantry Division, along with 56 crewmen and 194 gunners, for a total of 3,437 dead. Lieutenant Commander Underwood’s Spadefish pitched into the convoy and, at 11:09 p.m., ripped open the hull of escort carrier Shinyo. Wreathed in terrible fires, it succumbed with 1,104 crew members, leaving just 61 survivors.

According to Japanese historian Sadae Ikeda, some 176,000 Japanese soldiers and paramilitary personnel perished in ships sunk from all causes over the course of the war. That number raises an important point. According to Craig McDonald, while he is certain the figures he and John Alden used in their 2009 book were accurate, they recognized that their sources did not comprehensively cover all troop losses. Therefore, the 97,342 figure mentioned earlier—while constituting more than half of the total number of Japanese military personnel lost at sea—should be viewed as the floor, not the ceiling, on losses in submarine attacks.

In January 1945, Imperial Army General Headquarters published a circular, “How to Deal with Maritime Emergencies,” based on a study of troopship losses in the East China Sea. The document noted that the density of embarked troops per vessel had soared during the war: soldiers were packed into holds of requisitioned ships with bunks called “silkworm shelves” (kaiko-dana) stacked three high. Only extremely steep wooden ladders, completely inadequate for evacuation in an emergency, afforded access to the topside decks. The study recorded how torpedo strikes left some men unconscious and detailed the horrors that others faced. Some lost the will to live after floating in the water for a while, when they realized there was scant chance of rescue. Some committed suicide to avoid death by drowning. Some, exhausted, began to hallucinate and jumped into the ocean from rafts. Others become violent with fellow survivors.

Tragically, Allied advances had prompted the Japanese to also move tens of thousands of POWs by ship to more secure locations. The Japanese also impressed more slave laborers to boost war production. As a result, their deaths in ship losses soared: 11,699 POWs and slave laborers died at sea in 1944—nearly three-fourths of the war’s 15,774-death total. While the majority of these deaths resulted from U.S. submarine attacks, proportionately more POWs and slave laborers were exposed to attacks in the Southeast Asia hunting grounds of British submarines. These circumstances, and pure chance, produced an episode in September with the largest combined loss of Allied POWs and slave laborers in the entire war.

The 5,065-ton Junyo Maru was built in Glasgow in 1913 and acquired by Japan in 1927, but was now serving as an Imperial Army troop transport. On September 15, at the port of Batavia on Java, it took on about 2,200 Dutch, British, American, and Australian POWs, and some 4,500 Javanese slave laborers. They endured two days of hellish confinement before the ship sailed for Sumatra, where the POWs and slave laborers were to be employed. On September 18, the British submarine HMS Tradewind intercepted Junyo Maru and sank it in about 22 minutes with two torpedoes. Some 1,449 POWs and 4,171 slave laborers went down with the ship—a combined total of 5,620 deaths. It was the worst loss of life from a single ship in the Pacific War. This toll constituted nearly half of all the POWs and slave laborers lost in 1944. Approximately 880 POW and slave laborer survivors were rescued and continued to Sumatra, where ultimately only 96 POWs, and none of the slave laborers, survived the war.

1945

The immense destruction of Japanese shipping and warships in 1944 markedly reduced the number of potential targets for U.S. submarines the following year. Shipping traffic also plummeted due to aircraft based in the newly recaptured Philippines, and to carrier operations off Asia that severed the convoy routes from areas to the south that had provided Japan with vital imports, like oil. On top of that, land-based and carrier aircraft exacted a terrible toll on Japanese shipping in 1945. But the most lethal threat to Japanese shipping that year was the aerial mining campaign, mainly around the Home Islands. In 1,528 sorties, Mariana-based B-29s laid 13,102 mines. This campaign not only sank ships outright, but it also blocked entrance to repair yards so that there was no hope of restoring any seriously damaged ship to service. It further blocked entrance to the best ports and forced rerouting to inferior ports. This effort sank 283 merchant vessels of 396,371 tons and damaged beyond repair another 137 vessels.

Because of all these factors, U.S. submarines sunk only 156 vessels in 1945, almost a third of those during a foray in the Sea of Japan in June and July. Eight U.S. submarines were lost that year.

Summary

The charts above present the most significant data about the effectiveness of American submarines against Japanese soldiers in terms of total loss; loss by individual submarine; and, in contrast, loss in land battles.

Overall, the U.S. submarine force lost about 375 officers and 3,131 enlisted men during the war, out of some 16,000 who participated in war patrols. That is a 22 percent loss rate—the highest death rate within the American armed forces. The grim math discloses that for every U.S. submariner lost, about 28 Japanese soldiers perished. But the math also tells us that for every U.S. submarine sailor who died, many more Marines and soldiers lived. ✯