Flamboyant preacher ruled the stage, and the airwaves

[dropcap]M[/dropcap]INNIE KENNEDY KNELT. “Give me a little baby girl,” the Canadian farm wife prayed. “And I will give her unreservedly into your service, that she may preach the word.” In 1890, Kennedy gave birth to a girl she named Aimee, and promised God her daughter would save souls. Three decades later, Aimee Semple McPherson was the most charismatic and controversial evangelist in America, a flamboyant preacher whose tempestuous personal life inspired countless tabloid headlines, police inquiries, and a Broadway musical.

Young Aimee propped dolls on chairs and preached to them. At 12, she won a Christian oratory contest; at 13, she preached at church picnics. High school stole her faith. A science text declared the earth eons old and man a descendant of apes. If that’s true, Aimee thought, the Bible is false. She confronted her teachers and preachers. None could allay her doubts. Aimee rejected religion and began living a worldly life of reading novels, playing ragtime piano, and dancing—until she was 17 and, transfixed, heard the preaching of Robert Semple, a fiery Irish evangelist.

Semple was tall and handsome and Aimee fell in love with him. She burned her novels, her sheet music, and her dancing shoes. Within the year she and Semple married and traveled to China as missionaries. He died of malaria there in 1910, a month before she gave birth to daughter Roberta.

Aimee, 20, moved to New York. She wed Harold McPherson, an accountant, and settled in Rhode Island, where Aimee bore a son, Rolf. Housewifery bored and depressed her. She heard the voice of God. “Preach the Word!” He told her. “Preach the Word!”

In 1915, determined to become an evangelist, Aimee fled with Roberta and Rolf to her mother’s home in Canada. Her husband begged her to “act like other women” but Aimee left her children with their grandparents and set off. Her 1912 Packard convertible, a rolling billboard, blared slogans: “Jesus is Coming Soon” and “Where Will You Spend Eternity?” For six years, she roamed America, preaching in parks, cotton fields, tents, and auditoriums. She touted the “joy of salvation” while denouncing dancing, drinking, card-playing, and other worldly pleasures like theater. The last she condemned as the “devil’s workshop” even though theatricality was her shtick. Besides preaching, she sang, played piano, and spoke in tongues, drawing ever larger crowds—30,000 to San Diego’s Balboa Park in 1921—and moving onlookers to weep, faint, and roll on the ground. Some claimed Aimee healed their ailments. “They are cured by Christ,” she said.

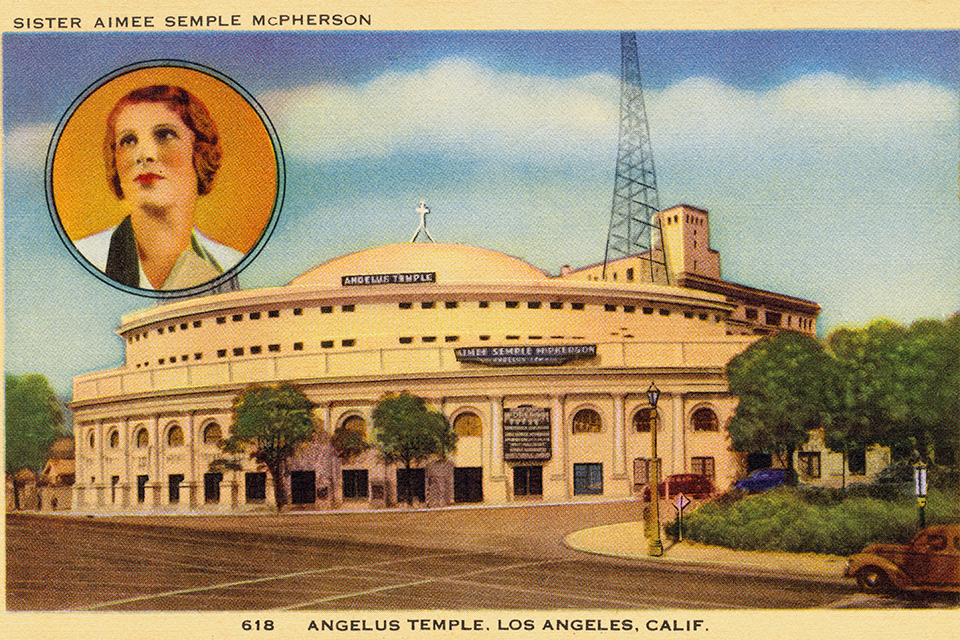

In 1921, Harold McPherson filed for divorce. Aimee settled in Los Angeles with her children and her mother, who handled the books as “Sister Aimee” created America’s showiest ministry. She founded the Church of the Foursquare Gospel and on Glendale Boulevard in Echo Park built Angelus Temple, which seated 5,000 and had a stage big enough to hold her 200-voice choir. In trademark white dress and blue cape, Aimee starred in “illustrated sermons”—musical plays she wrote and directed, basing some on Christ’s life, some on her own. For instance, when ticketed for a moving violation—a transgression widely covered by the press—she transformed the experience into a sermon, “Arrested for Speeding,” that she delivered in a police uniform, punctuating her recitation with the wails of a police motorcycle siren.

McPherson’s vivid theatrics attracted Hollywood stars, including Charlie Chaplin. An atheist, the Little Tramp nonetheless appreciated a good show.

“Half of your success is due to your magnetic appeal, half due to the props and the lights,” Chaplin told McPherson. “Whether you like it or not, you’re an actress.”

The self-proclaimed evangelist founded a Bible college and a magazine. She bought radio station KFSG to carry her sermons. She denounced Darwinism, defended Prohibition, and lobbied unsuccessfully to keep Los Angeles from legalizing dancing on Sundays. She peddled several autobiographies along with records of her sermons, plus souvenirs decorated with her picture. Her most popular sermon was entitled, “The Story of My Life.”

In May 1926, Aimee Semple McPherson went swimming at a Los Angeles beach…and vanished. Minnie Kennedy, thinking her daughter had drowned, announced, “Sister is with Jesus.” Followers and authorities searched for weeks without result. Rumors spread, linking Aimee’s disappearance to that of her friend, Kenneth Ormiston, a KFSG engineer whose wife had reported him missing. On June 23, Aimee appeared in Agua Prieta, Mexico, across the border from Douglas, Arizona, claiming that she’d been abducted. Newspapers ballyhooed the story while America debated: kidnapping or canoodling? Nothing came of inquiries into Ormiston’s private life, but the Los Angeles district attorney accused Aimee of perjury and obstruction of justice, charges he abruptly dropped. To this day, nobody knows what went on while Aimee was AWOL.

Notoriety made McPherson even more famous. Eager to cash in, she toured the country, pulling $5,000 a week telling her life story in vaudeville houses. She announced where she planned to be interred, then sold plots in that cemetery, promising buyers would rise with her at the Second Coming. Her mother criticized her for being greedy and told reporters Aimee had punched her. Aimee fired Mother Minnie—foreshadowing family friction to come years later that led McPherson to pinkslip daughter Roberta in another headline-generating spat.

For one of her showbiz sermons, Aimee hired a roly-poly singer, David Hutton, to play Pharaoh. In 1931, she and Hutton eloped. Next morning, as a publicity stunt, she invited press photographers into her boudoir. A few days later, a young woman sued Hutton for breach of promise. Aimee vowed her man would fight the suit and win. When a jury ruled against him, Aimee fainted, fell, and fractured her skull. Recovering, she fled to Paris without Hutton, who filed for divorce, saying he wasn’t Aimee’s “pet poodle.”

Despite—or perhaps because of—the lurid publicity about her personal life, Aimee kept filling Angelus Temple. During the Depression, she used donations to feed and clothe thousands in Los Angeles. During World War II, she produced elaborate patriotic extravaganzas and sold sheaves of war bonds.

In September 1944, Aimee was in Oakland, California, to preach “The Story of My Life,” when Rolf McPherson found his mother dead in her hotel room. She had overdosed accidentally on sleeping pills. At Angelus Temple, 45,000 mourners filed past her casket.

For the next 44 years, Rolf McPherson ran the Church of the Foursquare Gospel with no hint of flamboyance or scandal. The church went international, and now claims eight million members in 140 countries. In 2012, Foursquare Gospel invested $2 million in “Scandalous,” a Broadway musical about Aimee Semple McPherson written by Kathie Lee Gifford. The show died, closing after 29 curtains, and the church lost $2 million.