Remote Pacific Islands attracted settlers who dreamed of annexation

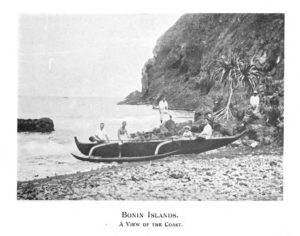

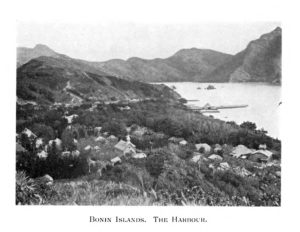

West by northwest of California, across 5,000 miles of Pacific Ocean, swells break against the volcanic rocks of the Bonins, a small island chain that takes its name from the Japanese for “uninhabited.” Japan is 600 miles north; Guam a thousand miles southeast. The 30 Bonins comprise about 32 square miles of land; nine-mile-square Chichi Jima, the largest of the islands, is dotted with 1,000-foot peaks. In the 1830s, Americans landed here, in an Orient where Japan and Korea rebuffed foreigners and China let them in at only a few ports. The pioneers held out against piracy and Imperial Japan, hoping the United States would annex the Bonins. That never happened in the way they envisioned it, but this motley of Americans boldly established a colony in hostile waters a half a world away from the United States, maintaining and expanding their settlement to the present day—gradually becoming Japanese, then Americans again, and back to Japanese, all the time holding onto their heritage and language.

Spanish sea captain Bernardo de la Torre was the first European to arrive at the Bonins in 1543. Japan credits their discovery to Sadayori Ogasawara in 1593. Japanese expeditions landed in 1670 and in 1675. By the 1790s, Japanese and European cartographers were including the Bonins on maps—inaccurately. All that time, the islands lived up to their name. But when Captain Frederick W. Beechey, sailing HMS Blossom, visited in 1827, he had a copper plate from his ship’s hull pounded into a tree trunk with an inscription claiming the chain for the British Empire. Beechey gave the largest island the name “Peel” after British Home Secretary Sir Robert Peel. Word of the Bonins’ existence spread across the Pacific as mariners updated charts and courses.

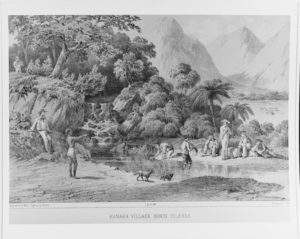

To the east 3,400 miles, the Hawaiian port of Honolulu was a human hodgepodge at which Polynesians, European sailors, and missionaries worked from tents on the beach.

Here and there were wood frame buildings. Vessels from around the world choked Honolulu harbor. Trading ships from the Pacific Northwest carrying otter pelts to China anchored for provisions, water—and sandalwood, forests of which blanketed Hawaii. Sandalwood brought top dollar in Chinese markets for use as incense. To wring maximum returns—he received a quarter of the take—King Kamehameha I rationed the sandalwood harvest, conserving that resource while enriching the crown.

Whaling ships came too, more than 100 a year. Grog shops and whorehouses lined the strand. Hawaiian women boarded ships for extended stays. For a sea-weary sailor, Honolulu was a dream come true. Farms and cattle ranches fed the fleet. A discontented seaman could jump ship certain of finding work as a farm or ranch hand or lumberjack, and when the mood struck catch an outbound vessel.

In 1819, Kamehameha I died. His son, namesake, and successor let loggers have all the sandalwood they wanted as fast as Hawaiians could fell it. Missionaries began arriving from New England, led by William Richards. God’s representatives saw the seamen as agents of Satan and whaling ships as “floating castles of prostitution.” Leaning on the Hawaiian court, clerics engineered controls on drinking and whoring, leading to friction. When Richards had a whaling captain arrested for taking four women aboard, the whaler’s crew fired on the missionary’s house. The king had to open a police station in Honolulu. In 1830, Hawaii ran out of sandalwood, impoverishing the work force that had depended on it.

An unemployed, hot-tempered native of Genoa, Italy, Matteo Mazzaro (also Mazarro), wanted to leave Hawaii for the Bonins. He asked British consul Richard Charlton to underwrite the outfitting of a schooner in which Mazzaro, his English friend John Millicamp, and companions would sail west and claim the orphan chain for the Empire, founding a settlement Mazzaro portrayed as pre-missionary Honolulu, only smaller.

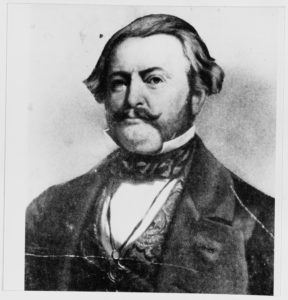

Charlton went along. Mazzaro and Millicamp enlisted Americans Aldin Chapin and Nathaniel Savory, and a Dane, Charles Johnson. Savory, 35, a sailor from Bradford, Massachusetts, had hurt a hand at sea; while he was ashore in Honolulu seeking a doctor’s care, his vessel hoisted anchor, leaving Savory high, dry, and nine-fingered. With 13 Hawaiian men and women, he and the other Westerners left Honolulu on May 21, 1830. In the schooner’s hold were pigs, goats, chickens, and a stock of yams, vegetables, and sugar cane plants Savory had brought to grow for making rum. Thirty-six days and 3,400 miles later, Mazzaro was hoisting the British flag over his hut on Chichi Jima, which had plenty of water and timber and waters rich in sea life.

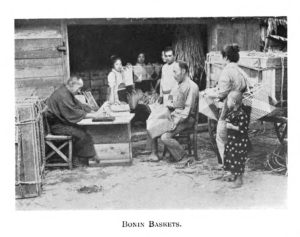

Settlers found the tropical climate excellent for farming and raising livestock. Savory processed cane sugar into rum. Comrades opened bordellos. Settlers favored dishes that had made it across the ocean from as far away as New England, such as a dumpling soup. Ships’ captains unable to find a friendly port in Japan flocked to the settlement for provisions and recreation. In 1833-35, 24 ships visited, 22 of them whalers. When female sex workers ran short, colonists kidnapped women from other island chains such as the Carolines and even Hawaii. An 1836 ship’s log entry regarding the island recorded male residents with “one or two wives,” unchecked carnality, and infanticide, sometimes at the hands of victims’ mothers.

The islanders fought chronically, with Mazzaro prominent among the brawlers. Neighbors mocked the Italian’s claims that the British had put him in charge of the enterprise. In response to Mazzaro’s Union Jack, Savory hoisted the Stars and Stripes over his hut. Islanders gravitated to Savory’s leadership.

In 1838, Mazzaro tried to hire a whaler to kill Savory. “He said for me to make friends with Savory and when he turns his head to beat his brains out with a club, and if that did not kill him, to stab him with a knife until dead and throw him into the sea,” the seaman told American naval officers. In 1842, Mazzaro, leaving Millicamp to represent him, sailed to Honolulu to convince the new British consul to recognize him as the Bonins’ British governor. The consul proffered another Union Jack and a letter “recommending” Mazzaro to serve as governor. Returning with those and more settlers, Mazzaro found Millicamp gone to Guam and Savory in control. The Union Jack’s days in the Bonins were over. Yet more settlers arrived in ones and twos from visiting whaling boats.

The island’s resident Washington family descends from a Portuguese African cabin boy who jumped ship in 1843, taking that last name. More arrivals, many of them Pacific islanders, came in 1846 aboard the whaling vessel Howard. Mazzaro died in 1848. Savory took in and wed his widow.

Lacking affiliation with a country of substance, the roughly 50 Bonin islanders were at the world’s mercy. In 1849, French whalers raided Chichi Jima, stealing provisions, Savory’s gold, and Savory’s wife. Savory described his spouse being thrown over a captor’s shoulder and struggling as he hauled her aboard; others said she not only went along willingly but showed the interlopers the way to the hidden gold. In 1850, Captain Thomas Page of the USS Porpoise reported that the crew of a vessel out of Hong Kong had kidnapped a woman from the Chichi Jima strand to sell elsewhere. Page expressed worry for the islanders. From time to time, American, British, and Russian warships anchored at the islands for extended periods, temporarily imposing order.

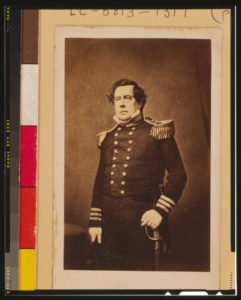

American commercial interests were expanding in the Orient. Driven by demand for whale oil, used for lamps, soap, and cooking (see “Up in Flames,” p. 34), many of the country’s 746 whaling ships were entering Japanese waters, risking violent mistreatment, even execution by beheading, for putting a foot ashore. To resolve the impasse, the United States sent an armada under Commodore Matthew Perry to open Japan. En route to Tokyo, Perry arrived in the Bonins on June 14, 1853. He landed two shore parties on Chichi Jima and sent a third to map the chain’s northern portion. For $50, Savory, the last of the original settlers, sold Perry 12 acres of land at Ten Fathom Hole, a bayside anchorage, to use as a navy coaling station. Perry hired Savory to operate the station, assisted by Seaman John Smith.

Renaming Chichi Jima Peel Island and writing a constitution titled “Organization of the Settlers of Peel Island Colony,” Perry appointed Savory chief magistrate and residents James Maitley and Thomas Webb councilmen. Perry left behind Seaman Smith, four cattle, five sheep, and six goats. Savory, 55, named his infant son Perry.

After his epic voyage and success in opening Japan’s markets, Perry, an avid advocate for annexing the Bonins, supplied Savory with seed, tools, and flags. In an 1856 speech in New York City, Perry stressed the islands’ strategic importance. But he died in 1858, and civil war drew American eyes away from Asia.

Perry’s mission had alerted Japanese officials to the greater world’s imminence and the Bonins’ strategic value. The islands were too close to Tokyo to be under a thumb not Japanese. In November 1861, Japan informed American ambassador Townsend Harris of the empire’s plans to occupy the Bonins. Harris commented only that he expected Japan to respect the rights of Americans already on the islands. A Japanese force reached the Bonins on January 19, 1862. The Japanese governor met with Savory, 67, to announce the annexation and to confirm settlers’ rights. The landing force distributed gifts of sake, cloth, and toys to the residents and built a warehouse, a shrine, and an administrative building. Japan officially named the main island and settlement Chichi Jima.

Japanese colonists landed in August to settle across Chichi Jima Bay from the American settlement. After a year that saw friction between the camps, the Japanese newcomers suddenly left, claiming to fear a British attack prompted by an incident in Yokohama that had left a Briton dead and spurred the Royal Navy to shell Japanese towns. The likelier reason was tension between Japanese and American islanders. Japanese officials turned management of abandoned structures and fields over to Savory as caretaker, saying they would be returning.

A tidal wave slammed the islands in 1872, causing considerable damage, including the loss of the detailed record Savory, in declining health, had been keeping since his arrival. Islander Benjamin Pease told the American legation in Yokohama in 1873 that the colony tallied 68 residents, including 25 “pure blood” Americans. Pease complained that the island’s 26 children went unschooled and nearly naked, voicing hope that the United States would assume control of the islands “again.” In 1874, Savory died. His eldest son, Horace Perry Savory, took control of the colony. In November 1875, the crew of a Japanese warship sailed into Chichi Jima Bay demanding to see the colony’s leaders, asking that they pledge loyalty to Japan, and offering interest-free loans to American residents becoming Japanese citizens. By 1882, all Americans in the Bonins had become naturalized Japanese.

In December 1876, Japan formally annexed the islands, the empire’s the first territorial acquisition. The government banned foreign settlement in the islands and offered settlers relocating from mainland Japan to the Bonins interest-free loans. Thinking to replicate Hawaii’s success with sugar cane, Japan clear-cut the islands’ forests. Descendants of Americans and Japanese colonists segregated themselves in two villages. The American community was called Chichi Jima—unofficially, “Yankeetown.” The other village, Omura, was Japanese. Though Chichi Jima was seen as an American community, most residents had Caucasian and Polynesian features, reflecting ancestry tracing to Caucasian, Hawaiian, Micronesian, Portuguese, and African roots. Their language evolved into a unique pidgin also called Bonin English, which borrowed from their Japanese neighbors. For example, “Are wa itsu taberu tabemomo” translates to “When is it you eat that food?” and “You no ojisantoo, he had lots of stories” means “Your grandpa too, he had lots of stories.”

The older generation refused to allow their children to intermarry with the Japanese. Suddenly the Americans, who never were overtly religious, built an Anglican church as if to underscore the message that they differed from the Japanese, who returned the sentiment. “When we boys left Yankeetown to go to Omura, we never went alone,” Charlie Washington, 91, recalled decades later. “The Japanese taunted us, called us barbarians or worse and a fight usually followed.”

These were the Bonins’ quiet years. Besides working small farms and provisioning passing ships’ crews, resident Americans also hired out as mariners. Other Americans came to the Bonins as sailors, like 17-year-old Jack London. The writer to be was a seaman onboard a three-masted seal-hunting ship when he and two friends took shore leave in 1893. London went on a ten-day bender, waking up on a stranger’s porch in time to return to his vessel, sans wallet and several articles of clothing.

Japan gave up raising sugar cane in the Bonins. That effort had ballooned the population to around 4,000 as Europe was about to erupt in what became World War I. After the war, hordes of construction workers—and farmers to feed them—arrived in the Bonins, influxes brought on by Japanese military buildups.

One, undertaken to create a massive yard for building warships at Chichi Jima, ended in 1924 when terms of the Washington Naval Conference were registered officially with the League of Nations—the world’s first attempt at arms control. The second buildup began in 1937 when Japan deepened its incursion into China.

After Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, life in the Bonin Islands took on a harsh edge. Police officers asked schoolchildren what language their families spoke at home. English-speaking parents were interrogated and the language banned. Americans had to take Japanese names. One of Nathaniel Savory’s grandsons burned his grandfather’s effects, including the flag Commodore Perry had given the old man. Civilian naval workers arrived, as did hundreds of farmers to feed military and civilian personnel.

As island-by-island fighting was creeping toward mainland Japan in February 1944, authorities in the Bonins began evacuating civilians, relocating 6,800. To supply food for the Imperial Army garrison, 825 men were ordered to stay behind. Four were descendants of original settlers: Simon and Jimmy Savory, Frank Washington, and Jeffrey Gilley.

American planes began to bomb the islands, prompting soldiers there to tie Gilley to a stake in the open for 24 hours in hopes that his Caucasian features would persuade attackers to veer away. The gesture made no difference, but Gilley survived. In September 1944, defenders shot down several attacking American planes, including one piloted by 20-year-old Lieutenant George H.W. Bush. Bush was the only one of nine airmen downed near Chichi Jima to evade capture by Japanese troops.

Transplanted to mainland Japan, American descendants from the Bonins encountered bias among native Japanese who refused to believe these seeming foreigners were countrymen. Police in Japan had to rescue an islander named Savory when he was mistaken for a downed American pilot and attacked with bamboo spears. Another displaced islander, Fred Savory, was working on the docks in Yokohama when soldiers returning from the Bonins told him their commanders had gone mad. Japanese officers at Chichi Jima, rattled by the fall of Iwo Jima, only 170 miles away, and coming under heavy American bombing attacks, had beheaded and cannibalized their eight American prisoners, the soldiers said. Jeffery Gilley, serving in the Bonin militia, unwittingly ate a gift from the garrison’s officers: human meat served with curried rice.

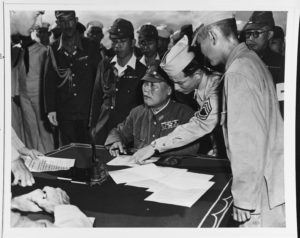

After Japan surrendered, American occupation troops suspected a cover up of late-war events on Chichi Jima. Fred Savory, who had returned to Chichi Jima with a Japanese wife, reported the rumors he had heard in wartime Japan. A Korean cleric held on Chichi Jima as a forced laborer named the offending Japanese officers. Fred Savory testified at their war crimes trial on Guam. In 1947 five former Imperial Army officers were hanged and eight were sentenced to between five and 20 years in prison.

In 1946, the impossible seemed on the verge of occurring. The United States declared the Bonins an American protectorate, ordering all civilians off the islands save 129 descendants of the original American settlers. A roster of island family names from U.S. naval records showed 15 Savorys, 11 Washingtons, five Webbs, three Gilleys, and two Gonzaleses. The families organized the Bonin Islands Trading Company to do business with the U.S. Navy. Among the explanations for allowing them to remain was that these Americans had suffered wartime discrimination at the hands of Japanese authorities and that their forefathers had assisted Commodore Perry. However, Chichi Jima, once a U.S. Navy coaling station, also housed nuclear weapons. As part of its management of that stockpile, the Navy bulldozed properties vacated by exiled Japanese and ran the Bonins for 23 years—“Navy Time,” Western residents called it. Islanders got free dental care and the Navy shipped produce harvested on the island at no cost. For the first time in decades, islanders grew up not speaking Japanese.

During Navy Time many American descendants worked for the U.S. and looked forward to becoming actual Americans. In 1956, islanders petitioned for American annexation, to no response. In 1968, without consulting the American descendants, the United States announced the return of the Bonins to Japan, with former Japanese colonists allowed back. Descendants such as the Washington, Webb, Gonzales, and Savory families complained of learning the news on the radio. American descendants had a stark choice: retain Japanese citizenship or become American citizens and repatriate to the United States. Three Savorys were among the handful that departed for the country their ancestors had left a century and a half before. The majority remained in the islands as Japanese citizens.

Initially some 600 Japanese relocated to the islands, arriving in 1969 and doubling in number by 1975. The island’s population peaked in 2000 at 2,445 residents, the American portion numbering a few hundred. The Navy Time generation of American descendants who decided to stay is now approaching its eighth decade, members gradually enlarging Chichi Jima’s Western graveyard.

Called by Japanese neighbors obeikei, or “half-blood,” reflecting the history of intermarriage between settlers and descendants with Pacific Islanders, these Bonin residents seem intent on maintaining traditions brought by original settlers in 1830 and flavored by Polynesian and other regional influences. John Washington, owner of a local inn, hoisted the Stars and Stripes each morning for decades well into his seventies. Many still attend the Anglican church where Isaac Gonzales had been the pastor up to a few years ago. Etsuko Savory taught her children how to make traditional New England dumpling soup.

With the dying out of the Navy Time generation, the American aspect of this former American outpost is rapidly shrinking. The Bonins have become a subject of academic studies as the only place where an Asian power rules a native people whose language is English.

This story appeared in the February 2021 issue of American History.