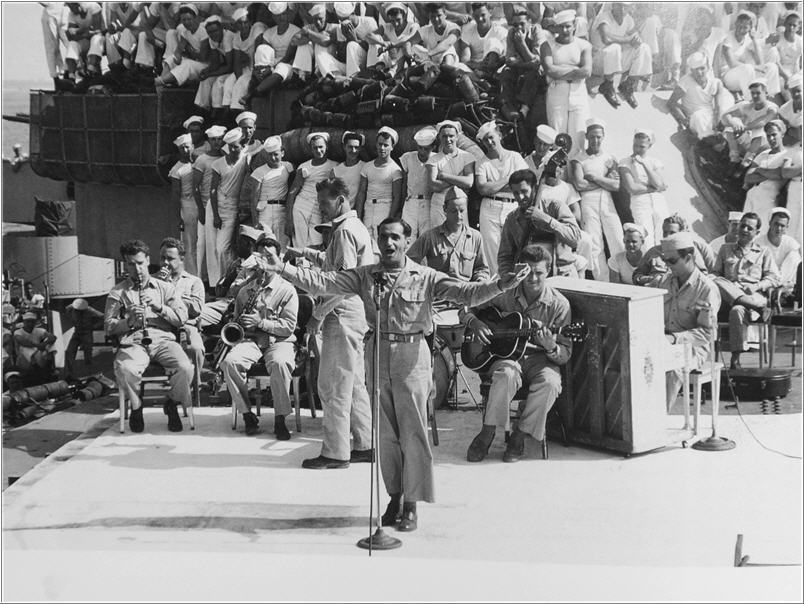

Composer’s greatest gift was an ear for the simple and the sweet

There are composers of American popular songs far more inventive than Irving Berlin, and lyricists far cleverer. But no American songwriter has so embedded his work into the American psyche. Berlin’s “Easter Parade” is still heard each spring, his “White Christmas” is inescapable in December, and the 4th of July is not the 4th of July without his “God Bless America.” As James Kaplan writes in a new Berlin biography, “alone of all the writers of the American Songbook, he could tap into something simply and profoundly American.”

(Yale, 2019, $26)

Israel Baline arrived in the United States from Russia as a child and grew up poor in a tenement in Manhattan’s Lower East Side. In 1911, at age 22, now calling himself Irving Berlin, he redefined American song with “Alexander’s Ragtime Band.” In two years, two million copies of the sheet music sold. He kept on punching them out: “Always,” “Blue Skies,” “Cheek to Cheek,” “There’s No Business Like Show Business.” His talent was innate. He could not read music; a musically skilled secretary would transcribe tunes he plunked out on an ancient upright. He wrote his final Broadway song in 1966, at 78, and then lived 23 more years.

Rare among songwriters, Berlin made himself a celebrity, and “though filled with insecurities, he always drove a very tough bargain when it came to protecting his music,” the author notes. As early as 1925, New York Times theater critic Alexander Woollcott published a Berlin biography. At least 14 more followed, including a half dozen for young readers, raising the question about the need for Kaplan’s. He worked closely with Berlin’s eldest daughter, but she is one of her father’s biographers, so revelations are sparse. Kaplan also sieved Berlin’s letters for quotes and harvested anecdotes from dusty articles. However, by and large there’s not much new here. The value of the book is that Kaplan adroitly mines the Berlinographical vein, delivering a sort of anthology of keeper quotes and stories. And he shows true skill at telling a driving story unconstrained by academic standards. When he lacks information, he breezily pivots with a “we may easily infer” or “might well have.”

Kaplan makes clear that the lack of complexity in Berlin’s music and wit in his lyrics was deliberate; with every revision he sought to simplify. “In Berlin’s hands,” Kaplan writes, “Simplicity was power.” —SCOTUS 101 columnist Daniel B. Moskowitz teaches adult ed courses on American popular music at American University and George Mason University.

By Walter Johnson

(Basic, 2020, $335)

Every city has a distinct back story, but St. Louis’s truly is unique. Set along the Mississippi near that river’s confluence with the Missouri, St. Louis has elements of each of the quadrants that define the United States, yet belongs to none. As Harvard professor Walter Johnson writes in his new book, here is ‘a city that is, at once, east and west, north and south.” In 1870 or thereabout, that centrality led to serious consideration being given to relocating the capital there.

The St. Louis story is so compelling that, Johnson admits, it has inspired many “truly excellent” histories. But his tale begins much earlier than others—in the 12th century, when in the vicinity native Americans maintained a settlement with 1,500 structures and 10,000 inhabitants. There, six centuries later, adventurers from New Orleans built the first westerly outpost of what would become the United States. In 1804 Lewis and Clark jumped off from St. Louis to map a path to the Pacific. All but 20 percent of the U.S. Army headquartered there. The population almost doubled between 1880 and 1900, when 22 rail lines converged there. The 1904 World’s Fair, which drew 20 million visitors, was staged concurrently with the Olympic Games. “During the summer of 1904, St. Louis was not simply the hub of the nation’s western empire—it was the center of the world,” Johnson writes. For decades after, local industry prospered. As the mainspring of World War II production, St. Louis made everything from aircraft engines to K-rations to enriched uranium.

Peace brought decline. The population shrank 13 percent between 1950 and 1960, and 17 percent more the next decade. Now 64th in population among American cities, St. Louis is one of only four to have lost more than 5 percent of its population since the 2010 census.

Johnson blames the St. Louis arc on capitalist greed and suppression by whites of Native Americans, then blacks. There are other valid interpretations. The city has suffered from the constant westward shift of investment and population: California has 13 cities larger than St. Louis. And city government made disastrous decisions, such as separating the municipality from the surrounding county, forgoing tax revenue from prosperous suburbs. But Johnson unspools the history of St. Louis with such an impressive mix of scholarly detail and anecdotal liveliness that one need not buy his central thesis to find Broken Heart an enlightening read. —SCOTUS columnist Daniel B. Moskowitz is a lifelong visitor to the St. Louis area, home to numerous aunts, uncles, cousins, and friends.

By Robert L. O’Connell

(Random House, 2019, $32)

Yet another biography—but an ingenious one that posits George Washington’s greatest feat as being not military or presidential skill but guiding history’s most successful revolution. Historian O’Connell ends his narrative in 1783, and his scholarship breaks no ground, but few readers will object to this lively, opinionated account.

O’Connell’s Washington grew up a loyal British subject and minor scion of the Virginia aristocracy. No intellectual, he shared goals with fellow virile young southern gentlemen: get land, get rich, get military glory. By the time the colonies’ relations with Britain soured, Washington had gotten all those. Historians credit courage and self-promotion over talent for powering the service in the French and Indian War that made him a hero to colonists, a reputation that later served him well. Retiring in 1758, he spent the interwar years as a wealthy planter. Indebted, like most of his ilk, to British agents, he shared the widespread opposition to Britain’s post-1765 efforts to tax the colonies. In 1775, when the Continental Congress decided to choose a general to lead patriot forces, Washington made no secret of wanting the job. Other candidates promoted themselves, but he was the unanimous choice.

Some historians portray Washington as a leader of irregulars a la Fidel Castro or Josip Broz, aka Marshal Tito. O’Connell stresses that Washington saw himself as a European-style commander leading a disciplined army in the mass open-field maneuvers doctrinaire in 18th century combat. As such, he remained an aristocrat to the core. In a delicious irony, revolutionaries from Robespierre to Lenin to Mao were educated intellectuals who rationalized cruelty and murder as necessary for the greater good. Unschooled and middle-brow, Washington abhorred but nonetheless tolerated ungentlemanly conduct by his soldiers. Few rebel Americans objected to persecuting colonial loyalists. No law of civilized warfare applied to Indians. O’Connell, laboring at his point, passes over much bad patriot behavior. Yet there’s no denying that British troopers, steeped in brutalizing Irish rebels, treated Americans harshly.

A scholar must sweat to characterize Washington as a brilliant strategist, but it’s a no-brainer to conclude that he was a brilliant politician who managed a ragtag army through a violent revolution, enduring many defeats yet never, even in his lowest moments, unleashing the malevolence subsequent revolutionaries loosed. For eight years, he pleaded for support from a rattle-brained Continental Congress that responded with its usual bumbles. Generals from Cromwell to the current gang of military dictators took the obvious step, but Washington never considered it. Even at the time European observers considered Washington’s accomplishments of forbearance and performance as almost superhuman, and O’Connell makes a convincing case that they were right. —Mike Oppenheim writes in Lexington, Kentucky