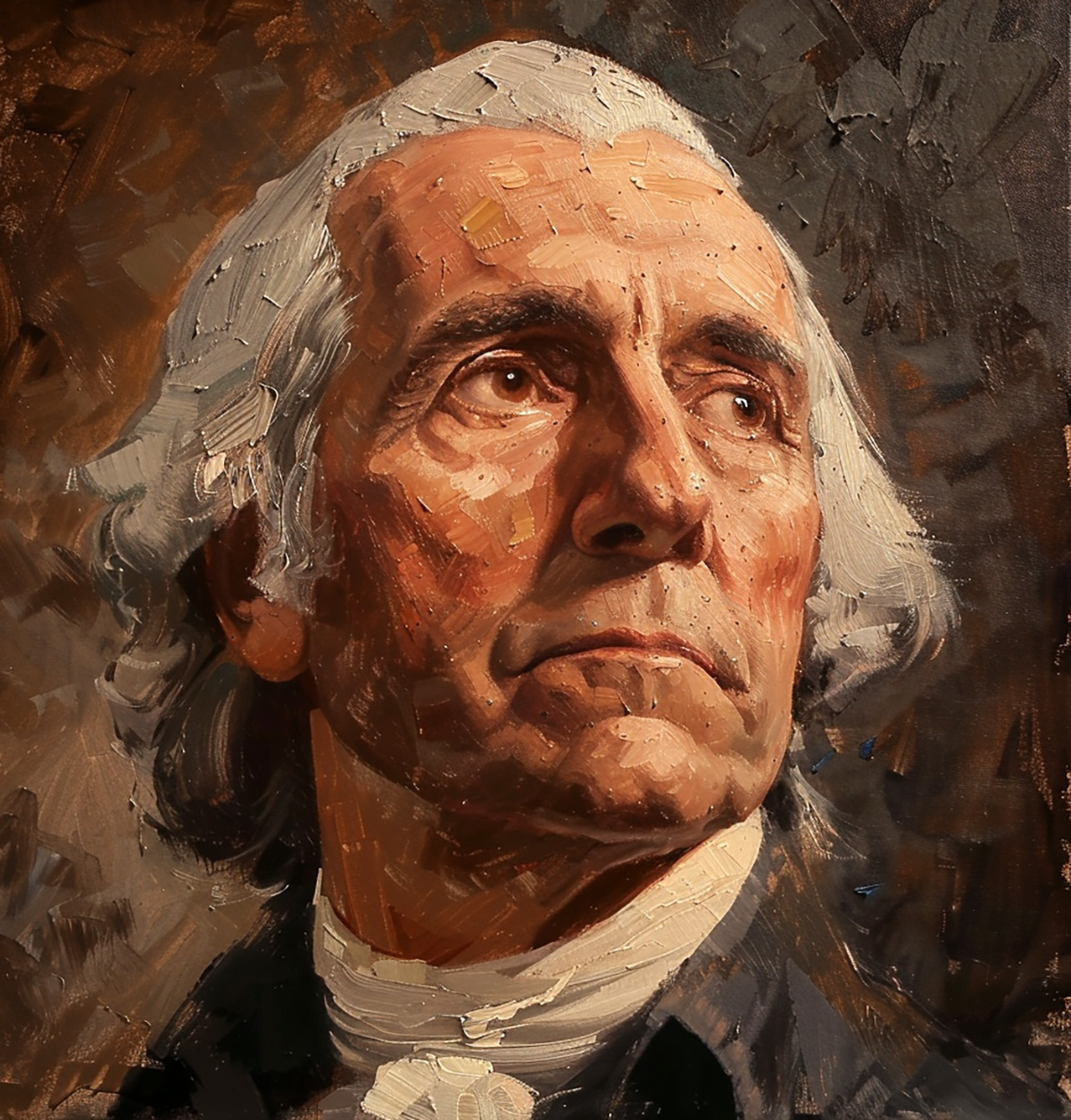

Inventing George Washington: America’s Founder, in Myth & Memory

By Edward G. Lengel; Harper

The Father of Our Country would be mightily bemused by his metamorphoses in American mythology. His dizzying transformations over the last two centuries make it seem like each succeeding generation of Americans cultivates collective amnesia to swallow new “facts” about George Washington while erasing the old.

With grace, wit and detail, Edward G. Lengel, editor-in-chief of the Washington Papers Project, traces the fascinating trail full of unexpected switchbacks marking who and what we’ve thought Washington was. He notes, with irony, that Washington’s primary concern in life was his enduring reputation. Then he proceeds to delineate, via a winning mix of humor and head-scratching, how far from Washington’s actual activities, demeanor, beliefs and world the tales proliferating around him have been— and also how much evidence, like his letters, has been lost, sold, stolen and frittered away.

Lengel points out that the revolutionary generation and its children transformed the real Washington into an idealized figure of lifeless marble. These first revisionists erased from the record the charming dancer and flirt who loved jokes, had a shrewd though not extraordinary intelligence, was formal with everyone except his beloved Martha, and showed a dash of the soldier’s irreverence and profanity.

The premier rewriter was George Washington Custis, “a ne’er-do-well and habitual liar who happened to be Martha Washington’s grandson.” Next came Parson Weems with the cherry tree and “I cannot tell a lie.” The Victorian era remade Washington, who rarely attended church and never knelt there, into a devout Christian. It’s a view that somehow persists: Fabricated prayers, supposedly Washington’s, are still cited to prove his deep piety by the likes of Pat Robertson and Glenn Beck.

Washington has been a stuffy and dull Edwardian gent; a wanton sexual conqueror (a wry twist to the innumerable “Washington Slept Here” claims); a greedy materialist (this during the 1920s, when his image shilled for countless products); and on and on. By the close of this compelling book, he can seem more like a mirror for America’s collective unconscious than a great man Americans have sought to understand. There are lessons here. Historical interpretations are revisited and revised every generation or so. In part that’s because evidence changes. But it’s also because how we look at history, what we look to learn from it, varies.

Popular culture tends to reduce complex people facing complicated issues to stock characters in melodrama or farce. Historians, of course, are not immune to those same impulses. But by building arguments on evidence, the best—like Douglas Southall Freeman, whose seven-volume Washington biography in the 1950s was the first to be truly definitive—try to avoid tabloid speculations and wishful projection.

What matters most about a towering figure like Washington is not whether he was a plaster saint or had clay feet, but how, foibles and all, he strove to realize ideals as best he could. In the process, he reached high and created an enduring, if far from simple, legacy that has made him, as he wished to be, immortal.

Originally published in the February 2011 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.