October 8, 1918, was a hard morning for the 2nd Württemberg Landwehr Division at Châtel Chéhéry, France. The German division’s infantry regiments, the 122nd, 120th and 125th, were barely holding onto their piece of the Argonne Forest against an attack by the U.S. Army’s 82nd Division. Fortunately for the Germans, the Argonne favored the defense — and the Americans favored it further by attacking up a funnel-shaped valley right into a deathtrap.

In the thick of the fight was Lieutenant Paul Jürgen Vollmer. Vollmer, or ‘Kuno, as his friends called him, was a highly decorated officer who had recently assumed command of the 120th Württemberg Landwehr Regiment’s 1st Battalion, most of whose soldiers were from Ulm (in the semiautonomous German state of Württemberg), where Vollmer had been the assistant postmaster before the war.

Vollmer was directing his troops against the Americans when his battalion adjutant, Lieutenant Karl Glass, approached. Vollmer hoped that this was not another report that the Americans had penetrated the German lines. Such rumors had been common since October 2, when the so-called Lost Battalion of the U.S. 77th Infantry Division broke through a few miles west of his sector. Vollmer was relieved to hear that elements of the Prussian 210th Reserve Infantry Regiment had just arrived at his battalion command post 200 yards up the valley. The 210th was what Vollmer needed to push the Americans out of this portion of the Argonne. Vollmer told Glass to follow him to meet with the 210th’s commander, since they had only one hour to be ready for the counterattack.

Upon arriving at his headquarters, Vollmer was appalled to find that 70 soldiers of the 210th had laid down their arms and were eating breakfast. When he rebuffed them for their lack of preparedness, the weary Prussians replied, We hiked all night, and first of all we need something to eat. Vollmer told Glass to go back to the front and ordered the 210th to move quickly. He then wheeled around to rejoin his battalion.

Suddenly, down the side of the far hill, a group of German soldiers came running to the command post yelling, Die Amerikaner Kommen! Then, off to the right, Vollmer saw a group of 210th soldiers drop their weapons and yell, Kamerad, their hands high in the air. Bewildered, Vollmer drew his pistol and ordered them to pick up their weapons. Behind Vollmer came several Americans charging down the hill. Believing it was a large American attack, the 210th surrendered. Before Vollmer realized what had happened, a large American with a red mustache, broad features and a freckled face had captured him as well. That Yank, from the 82nd Division, was Corporal Alvin C. York.

Much has been written about York, but all the previous accounts have one significant flaw: They do not tell the German side of the story. In the course of recent research, hundreds of pages of archival information from across Germany have come to light, uncovering the full story of what happened on October 8.

October 7, 1918 — Initial German Defense

The German side of York’s story began on October 7, as the 2nd Württemberg Landwehr Division was preparing defensive positions along the eastern edge of the Argonne. Vollmer’s 1st Battalion, 120th Regiment, was the last of the division to pull back to the valley behind Châtel Chéhéry to serve as the reserve. This was welcome news for Vollmer’s men, who had been in the thick of the fighting since the Americans launched their Meuse-Argonne offensive on September 26, but the 10-kilometer move, harassed by American artillery, took most of the day before the battalion finally arrived near Châtel Chéhéry.

While Vollmer’s men were on the march, the U.S. 82nd Infantry Division moved into Châtel Chéhéry and prepared to attack Castle Hill and a smaller position a kilometer to the north, designated Hill 180 by the Americans but called Schöne Aussicht (Pleasant View) by the Germans. Both objectives were important, but Castle Hill, or Hill 223, as the Americans called it, was vital. Whoever controlled it controlled access to that sector of the Argonne. Elements of the German 125th Württemberg Landwehr, the Guard Elizabeth Battalion and the 47th Machine Gun Company were given the mission of holding that hill, under the overall command of Captain Heinrich Müller.

On October 7, the 1st Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment of the 82nd Division attacked. Battalion Müller fought tenaciously but was pushed back to the western slope of Castle Hill. There, the Germans held on through the night at great loss and even attempted a counterattack. The 82nd Division also captured Hill 180. The near-complete losses of Castle Hill and Pleasant View put the Germans’ grip on the Argonne at serious risk.

General Max von Gallwitz, the German army group commander in the region, monitored these developments with grave concern and directed the 45th Prussian Reserve Division’s 212th Reserve Infantry Regiment to help the 125th Landwehr to retake Pleasant View and the 210th Reserve Infantry Regiment to assist the 120th Landwehr in recapturing Castle Hill. Those counterattacks would occur at 1030 hours on October 8. Vollmer would lead the assault on Castle Hill.

As the 2nd Württemberg Division prepared its defenses on October 7, Vollmer’s 4th Company commander, Lieutenant Fritz Endriss, identified gaps between his unit and the 2nd Machine Gun Company. One of Endriss’ platoon leaders, Lieutenant Karl Kübler, told Vollmer, I regard our situation as very dangerous, for the Americans could easily pass through the gaps in the sector of the 2nd Machine Gun Company and gain our rear. Vollmer directed Kübler to establish liaison with the 2nd Machine Gun Company. Failing to do that, Kübler sent Vollmer a message, I will, on my own responsibility, occupy Hill 2 with part of 4th Company. But Vollmer replied, You will hold the position to which you have been assigned.

October 8 — American Attack and German Counterattack

Three significant threats faced General Georg von der Marwitz, the German Fifth Army commander, on October 8. First, there was the Amerikaner nest along the western edge of the Argonne Forest, where an isolated element of the 77th U.S. Infantry Division was proving to be more than the neighboring 76th German Reserve Division could handle. That saga began on October 2, when 590 American soldiers penetrated a mile into German lines and settled down for five days in a 600-meter-long pocket. Despite several concerted German attacks, the Americans refused to surrender. Meanwhile the 77th Division launched attack after attack to relieve its Lost Battalion. Although unsuccessful thus far, these attacks were taking a heavy toll on the 76th Reserve Division. If the 76th failed to eliminate the Lost Battalion, Marwitz’s flank would be exposed.

A second problem was the advance of the U.S. 82nd and 28th divisions to secure the eastern part of the Argonne, which could sever German lines of communication in the forest and protect the flank of the main American attack in the Meuse River valley. The third trouble spot, and the most dangerous to the German Fifth Army, was the Meuse Valley, just east of the Argonne Forest. It was there that General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Force, sent the bulk of his First Army with the goal of ultimately cutting the main German supply artery in Sedan, some 30 miles to the north.

The 2nd Landwehr Division chronicled the German predicament in the region. Concerned about the situation, general headquarters committed elements of the 1st Guard Infantry Division, a portion of the 52nd Reserve Division, the 210th and 212th regiments of the 45th Reserve Division and the Machine Gun Sharpshooters of Regiments 47 and 58 to the fight. Headquarters reports stated: We had to stop the enemy’s main attack, which was now east of the Aire [in the Meuse River valley]. So our artillery around Hohenbornhöhe was used to provide fires against his flank.

Meanwhile, German lookouts reported American soldiers making their way toward Castle Hill. This was the 2nd Battalion, 328th Infantry Regiment, 82nd Division — York’s battalion — which would attack via Castle Hill in a northwesterly direction after a 10-minute artillery barrage. The battalion would advance one mile across a funnel-shaped valley and seize a dual objective: the Decauville rail line and the North-South Road. These were the main German supply lines into the Argonne. The Americans had no idea that the Germans had positioned more than 50 machine guns and dug in several hundred troops to kill anything that dared move into that valley.

Fog blanketed the Aire River valley below the Argonne early on October 8. Things started to look up for Vollmer after the 7th Bavarian Sapper Company, under a Lieutenant Thoma, and a detachment of the 210th Prussian Reserve Regiment reported for duty. He placed the two units among the gaps on Hill 2 that Kübler and Endriss had previously complained about. It was 0610 hours.

Suddenly, out of the early morning fog, the Germans heard the uproar of an enemy infantry force attacking in the valley, where the stillness was shattered by the whine of ricocheting bullets. The Americans headed into the valley without a preparatory barrage because their supporting artillery unit had not received word to fire. The alarm was sounded across the 2nd Landwehr Division, whose troops quickly manned their positions. The American advance was immediately contested by Battalion Müller, which held on until it ran out of ammunition. After that, the Germans retreated across the valley to the forward trenches of the 125th Regiment. With Battalion Müller out of the way, the Americans cleared Castle Hill and plunged into the valley. They were greeted with heavy rifle and machine gun fire from hundreds of German soldiers dug in on the three surrounding hills. Vollmer moved forward with his battalion to bolster the 2nd Machine Gun and 7th Bavarian companies, which bore the brunt of the attack. After weeks of setbacks, it seemed that at last the Germans would take back the initiative in the Argonne. Alvin York later described that crucial engagement:

So you see we were getting it from the front and both flanks. Well, the first and second waves got about halfway across the valley and then were held up by machine gun fire from the three sides. It was awful. Our losses were very heavy. The advancement was stopped and we were ordered to dig in. I don’t believe our whole battalion or even our whole division could have taken those machine guns by a straightforward attack.

The Germans got us, and they got us right smart. They just stopped us dead in our tracks. It was hilly country with plenty of brush, and they had plenty of machine guns entrenched along those commanding ridges. And I’m telling you they were shooting straight. Our boys just went down like the long grass before the mowing machine at home. So our attack just faded out. And there we were, lying down, about halfway across, and no barrage, and those German machine guns and big shells getting us hard.

Among the Americans trapped in that fight was Sergeant Harry Parson, who ordered Acting Sergeant Bernard Early to lead a platoon of 17 men behind the Germans and take out the machine guns. York was part of that group. While the three American squads moved toward German-occupied Hill 2, a terrific commotion shook the area as American artillery belatedly opened up in support of the besieged 328th Infantry. The barrage inadvertently covered the movement of Early’s men, who found a gap in the lines. They made their way through it and into the German rear area. Despite that, Vollmer felt confident of victory. As the German 120th report stated: Without any artillery preparation, the adversary launched a violent attack and there was heavy fighting….The enemy was repulsed almost everywhere. 1st BN absorbed the brunt of the enemy attack without wavering, due to its good defensive position.

It was at that point in the fight that Vollmer, learning from Lieutenant Glass that the 210th had at last arrived, returned to his command post to find the 210th eating breakfast. He was taken prisoner before he had a chance to rectify the situation. Glass, who returned to the front lines moments before Vollmer departed, went back to the command post to report that he had seen American troops moving on the hill above. Before he realized it, Glass too was York’s prisoner. Everything occurred so suddenly that both Vollmer and the 210th Regimental soldiers believed that this was a large surprise attack by the Americans.

As the 17 Americans busily gathered their 70-plus prisoners, the 4th and 6th companies of the 125th Württemberg Landwehr on Humser Hill saw what was happening below. They signaled to the captured Germans to lie down and then opened fire. The hail of bullets killed six and wounded three of their captors. Several prisoners were also killed by the machine-gunners, which caused the surviving captured men to wave their hands wildly in the air and yell, Don’t shoot — there are Germans here! Lieutenant Paul Adolph August Lipp, commander of the 6th Company, had his men aim more carefully. He brought up riflemen to join the machine-gunners in killing the Americans.

Of the eight American survivors, Corporal York was the only noncommissioned officer still standing. He worked his way partly up the slope where the German machine-gunners were. For the gunners to fire at York, they had to expose their heads above their positions. Whenever York saw a German helmet, he fired his .30-caliber rifle, hitting his target every time.

Vollmer, the nearest to York, was appalled to see 25 of his comrades fall victim to the Tennessean’s unerring marksmanship. At least three machine gun crews were killed in this manner, all while York, a devout Christian who did not want to kill any more than he had to, intermittently yelled at them to Give up and come on down. Meanwhile Lieutenant Endriss, seeing that Vollmer was in trouble, led a valiant charge against York. York used a hunting skill he learned when faced with a flock of turkeys. He knew that if the first soldier was shot, those behind would take cover. To prevent that, he fired his M1911 Colt .45-caliber semi-automatic pistol, targeting the men from the back to the front. The last German he shot was Endriss, who fell to the ground screaming in agony. York later wrote in his diary that he had shot five German soldiers and an officer like wild turkeys with his pistol.

Vollmer was not sure how many Germans were killed in that assault, but knew it was a lot. Worse yet, his wounded friend Endriss needed help. In the middle of the fight, Vollmer, who had lived in Chicago before the war, stood up, walked over to York and yelled above the din of battle, English? York replied, No, not English. Vollmer then inquired, What? American, York answered. Vollmer exclaimed: Good Lord! If you won’t shoot any more I will make them give up.

York told him to go ahead. Vollmer blew a whistle and yelled an order. Upon hearing Vollmer’s order, Lipp told his men on the hill above to drop their weapons and make their way down the hill to join the other prisoners.

York directed Vollmer to line up the Germans in a column and have them carry out the six wounded Americans. He then placed the German officers at the head of the formation, with Vollmer in the lead. York stood directly behind him, with the .45-caliber Colt pointed at the German’s back. Vollmer suggested that York take the men down a gully in front of Humser Hill to the left, which was still occupied by a large group of German soldiers. Sensing a trap, York took them instead down the road that skirted Hill 2 and led back to Castle Hill and Châtel Chéhéry.

Meanwhile, forward of York and the prisoners was Lieutenant Kübler and his platoon. He told his second in command, Warrant Officer Haegele, that things just don’t look right. Kübler ordered his men to follow him to the battalion command post. As they approached, he was surrounded by several of York’s men. Kübler and his platoon surrendered. Vollmer told them to drop their weapons and equipment belts.

Lieutenant Thoma, the 7th Bavarian commander, was not far off and heard Vollmer’s order to Kübler to surrender. Thoma ordered his men to follow him with fixed bayonets and yelled to the 100-plus German prisoners, Don’t take off your belts! Thoma’s men took a position near the road for a fight. York shoved his pistol in Vollmer’s back and demanded that he order Thoma to surrender.

Vollmer cried out, You must surrender! Thoma insisted that he would not. It is useless, Vollmer said. We are surrounded. Thoma then said, I will do so on your responsibility! Vollmer replied that he would take all responsibility. With that, Thoma and his group, which included elements of the 2nd Machine Gun Company, dropped their weapons and belts and joined the prisoners.

As the large formation crossed the valley, York’s battalion adjutant, Lieutenant Joseph A. Woods, saw the group of men and, believing that it was a German counterattack, gathered as many soldiers as he could for a fight. After a closer look, however, he realized that the Germans were unarmed. York, at the head of the formation, saluted and said, Corporal York reports with prisoners, sir.

How many prisoners have you, Corporal?

Honest Lieutenant, York replied, I don’t know. Woods, who must have been stunned but kept his composure, ordered, Take them back to Châtel Chéhéry, and I will count them as they go by. His count: 132 Germans.

German Line in the Argonne Shattered

York’s men frustrated the German counterattack plan and bagged elements of the 120th Regiment, 210th Prussian Reserve Regiment, 7th Bavarian Company, 2nd Machine Gun Company and 125th Landwehr. This cleared the front and enabled the Americans to press on up the valley to take their objective, the Decauville rail line and the North-South Road. The German line was broken, and the 120th Landwehr would never recover from the day’s losses. Its report stated: The flank of 6th Company reported an enemy surprise attack. Next, the remnant of 4th Company and personnel from the 210th Regiment were caught by this surprise attack, where Lieutenant Endriss was killed. The company was shattered or was captured. Also First Lieutenant Vollmer ended up in the enemy’s hands. Now the situation was worse.

The planned German counterattack to take Castle and Pleasant View hills had been preempted by York and his men. If the 82nd Infantry Division pressed the attack now, it could cause the collapse of German defenses in the Argonne and lead to the capture of thousands of troops, supplies and artillery. But the American 328th Infantry had taken such a beating that it did not take advantage of this opportunity. Shortly after that the Germans were ordered to withdraw from the Argonne. The 120th Wurttenberg Infantry’s report noted:

[We received] the depressing order at 1030 to withdraw. In good order did we move. We did have some luck….There was no fire on the North-South Road. But we did see terrible things on the road. The results of the artillery; dead men, dead horses, destroyed vehicles blocking the way and destroyed trees were scattered to and fro. And what about the enemy? The North-South Road was closed by machine gun fire. This happened around 1200….It was amazing that the Americans did not press the attack. In the afternoon of 8 October, the headquarters of 3rd and 5th Army ordered a withdrawal from the Argonne line.

On October 9, the final order was issued to withdraw into the fortified Hindenburg Line for the final defense before the war ended. It was now that General von der Marwitz, the leader of 5th Army, gave the last word, the 120th’s report stated. We needed to occupy the secondary defensive positions further back. In the evening of 9/10 October, the regiment departed from the Argonne. The German soldiers gave so much after hard battles since 1914 — more than 80,000 dead were left here. American artillery briefly hit the Humserberg line during the retreat and always there was the shrapnel. We were dead tired, too tired to contemplate, but able to hold onto hope.

Postscript

Paul Vollmer served on the Western Front for four years. He fought with the 125th and 120th Württemberg Landwehr Infantry regiments in 10 campaigns and was awarded the Iron Cross 2nd Class in 1914, the Knights Cross 2nd Class in 1915 and the Iron Cross 1st Class and the Queen Olga of Württemberg Medal in 1918. Released in 1919, he moved to Stuttgart, where he again became a postmaster. In 1929 Vollmer was asked to provide a statement about the events of October 8, 1918, to the German Archives in Potsdam, which he did not want to do. After several formal requests, he arrived to answer questions. He was visibly uneasy about submitting a formal report. Vollmer insisted that there was a large group of Americans, not just York and his small squad. It must have seemed impossible that so few men could have captured so many highly trained German soldiers.

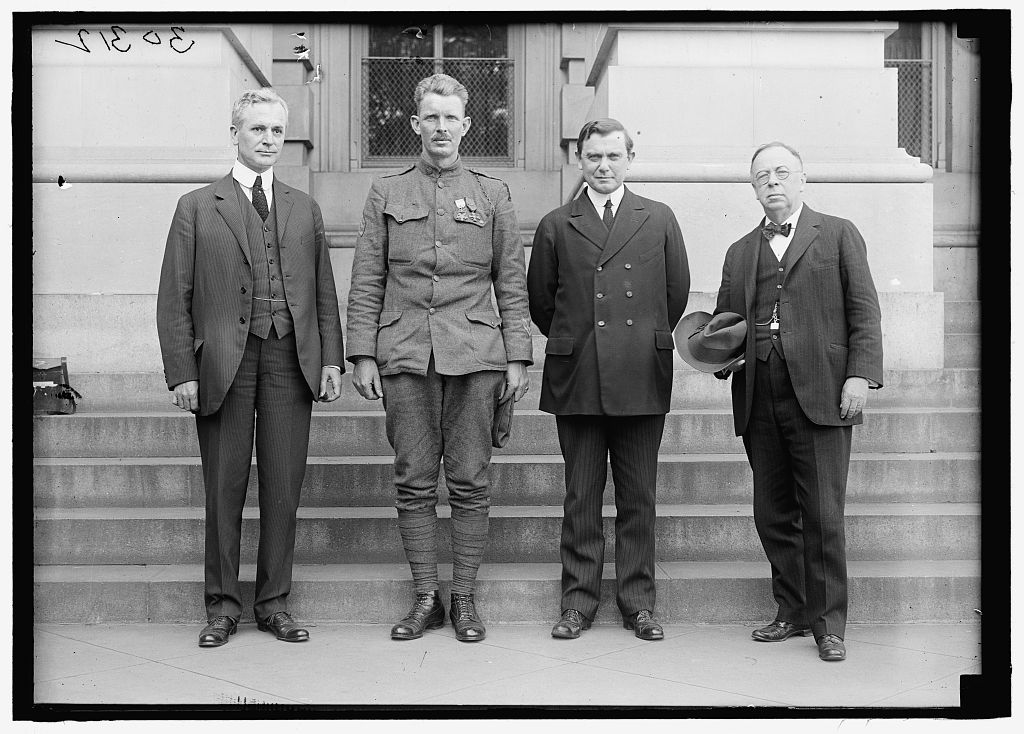

Alvin Cullum York was promoted to sergeant and received the Medal of Honor for his deeds of October 8. He was also awarded the Distinguished Service Cross, the French Croix de Guerre and several other medals. After the war, he returned to his hometown of Pall Mall, Tenn., where the people of his state gave him a house and a farm. He married his sweetheart, Gracie Williams, and they raised seven children — five boys and two girls. The faith that brought him through the war stayed with him throughout his life. An October 1918 diary entry just after the Argonne fight summarized his view of life: I am a witness to the fact that God did help me out of that hard battle; for the bushes were shot up all around me and I never got a scratch.

This article was written by U.S. Army Lt. Col. Douglas Mastriano and originally published in the September 2006 issue of Military History magazine. For more great articles be sure to subscribe to Military History magazine today!